Orthopaedic surgeons on call should thoughtfully consider and thoroughly evaluate a patient for the causes of pneumarthrosis when consulted for NSTI.

Leland CR, Nam HH, Bernstein DN, Harper CM, Appleton PT, Ibrahim IO.

Introduction: Necrotizing soft-tissue infection (NSTI) is a life- and limb-threatening diagnosis, warranting careful evaluation. However, intra-articular gas and soft-tissue emphysema, which are commonly associated with NSTI, may also be observed after traumatic arthrotomy, joint dislocation, and prior instrumentation.

Case Report: We present a 59-year-old woman in extremis from septic shock with left glenohumeral joint pneumarthrosis and emphysema extending to her posterior scapular musculature. While concerning for NSTI, physical examination was discordant. Review of pre-transfer documentation revealed prior instrumentation with an intraosseous line that pierced the left acromion process and violated the glenohumeral joint space.

Conclusion: NSTI is a critical diagnosis, particularly in the sick patient with hemodynamic instability, poor infectious source control, and soft-tissue emphysema. Discordant physical examination should raise suspicion for other etiologies such as traumatic arthrotomy, joint dislocation, or recent instrumentation.

Keywords: Necrotizing soft-tissue infection, intraosseous access, source control.

Necrotizing soft-tissue infection (NSTI) is a life- and limb-threatening diagnosis with an annual incidence of 10 cases/100,000 persons and in-hospital mortality up to 20% [1,2,3]. Although classic signs include bullae, skin necrosis, crepitus, and radiographic emphysema [4,5,6], these are absent in more than one-half of patients [4,5,7]. While clinical risk instruments, such as the laboratory risk indicator for necrotizing fasciitis (LRINEC) score, can aid in diagnosis [8], clinical suspicion takes precedent in diagnosis and management [7]. Emergent operative exploration is considered standard of care to exclude NSTI [7]. However, operative debridement is not benign, and amputation, performed in up to 25% of cases, is exceedingly morbid [2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9].

Intra-articular gas and soft-tissue emphysema are commonly associated with NSTI [6], particularly in patients with comorbid conditions, hemodynamic instability, and poor infectious control. However, they may also be observed after traumatic arthrotomy, joint dislocation, and prior instrumentation. We present a case of a critically ill patient with multiple possible sources of sepsis and suspicion for NSTI of the upper extremity. However, outside hospital imaging revealed an intraosseous line improperly placed through the patient’s left acromion into the left glenohumeral joint, offering an etiology for the deep tissue emphysema. To our understanding, this is the first case describing a suspected NSTI able to be excluded clinically due to malpositioned intraosseous vascular access. Institutional Review Board approval was obtained as the patient was unable to provide informed consent.

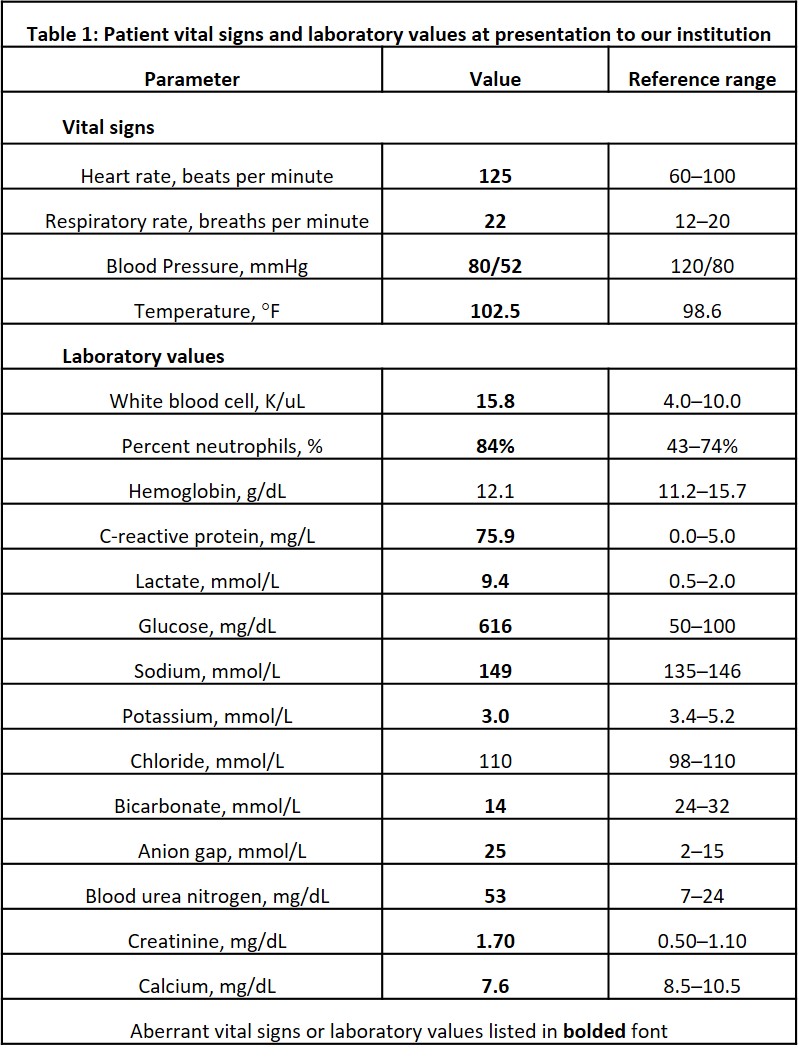

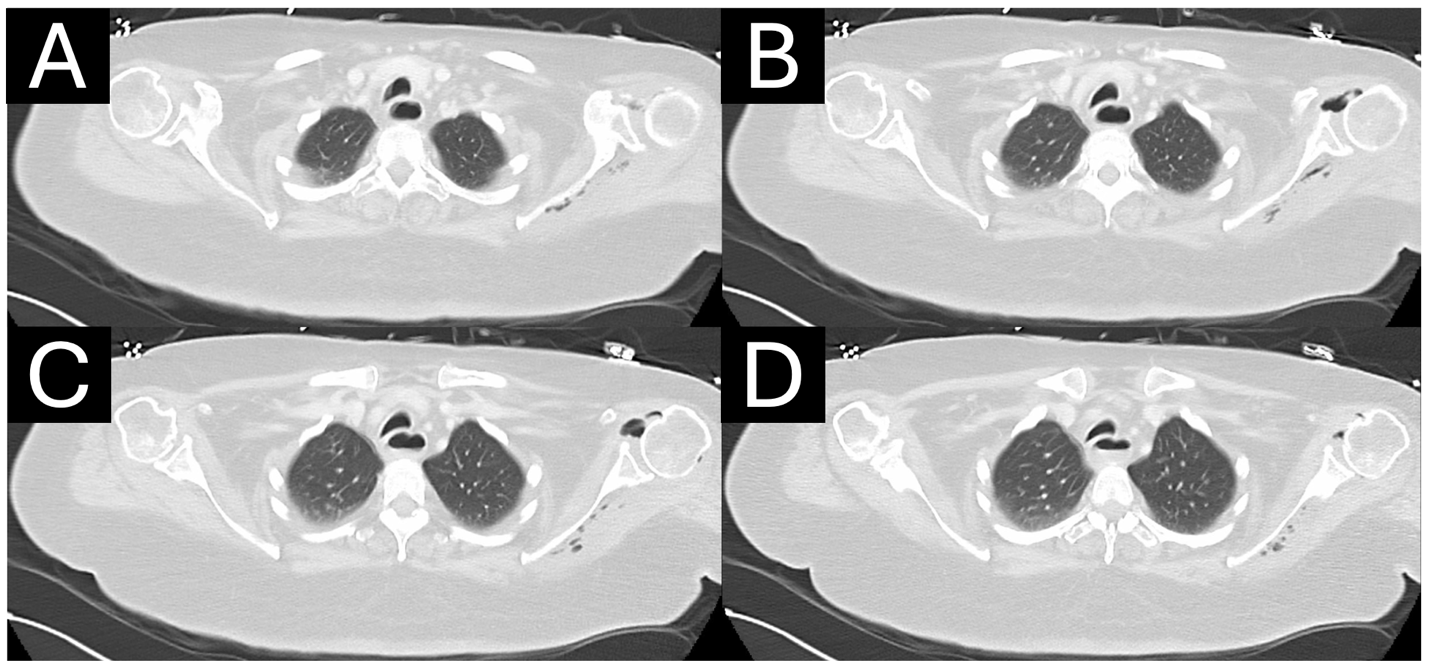

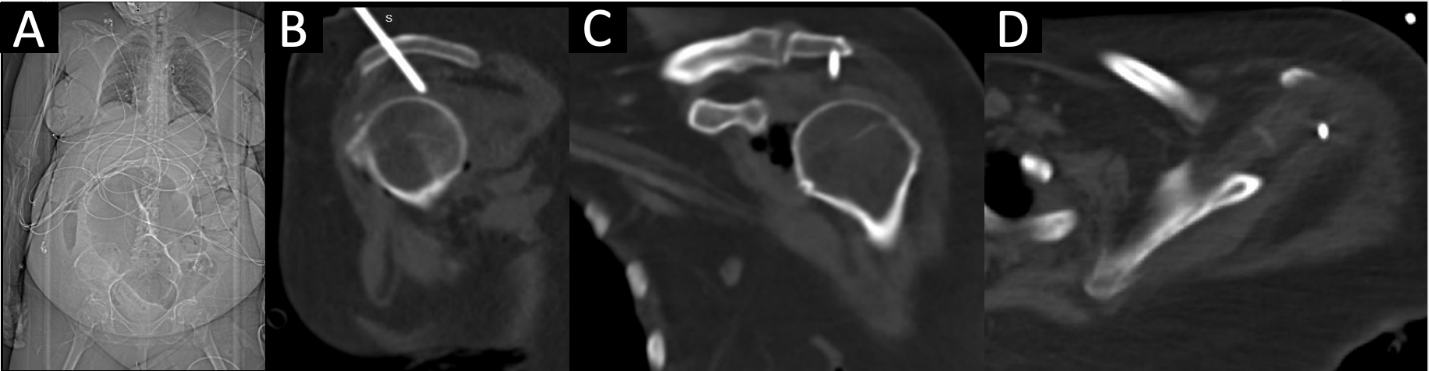

A 59-year-old, right-hand-dominant woman presented as a hospital transfer to the medical intensive care unit of an urban, quaternary academic referral center in extremis and septic shock of etiology and duration of 1 day. She initially presented to an outside emergency department from her long-term care facility with altered mental status and hypotension. Initial vital signs and laboratory values at our institution are presented in Table 1. Early diagnosis of sepsis or septic shock is crucial for prompt initiation of treatment. Time to antimicrobial therapy administration has been reported to be one of the most important interventions that decrease mortality in septic patients [10]. , vasopressin, piperacillin-tazobactam, and linezolid were administered before transfer. Zosyn and vancomycin were administered again upon arrival to our facility. The patient was observed to be in a hyperosmolar hyperglycemic state with lactic acidosis and noted to have several possible infectious sources, including a Stage IV sacral decubitus ulcer, malpositioned gastrojejunostomy tube, urinalysis demonstrating urinary tract infection (UTI) (with history of vancomycin-resistant enterococcal UTI), and chest imaging consistent with pneumonia. Computed tomography (CT) of the chest was also notable for glenohumeral pneumarthrosis with extension of deep tissue emphysema to the posterior scapular musculature concerning for necrotizing soft-tissue infection (Fig. 1a, b, c, d). The LRINEC score 8 was 9 scores of 8 or higher have been shown to be associated with NSTI, but its positive predictive value is reported to be 35% [11,12]. Given the patient’s hemodynamic instability, lack of infectious source control, LRINEC score, and imaging findings, orthopedic surgery was consulted to exclude left upper extremity NSTI.

Table 1: Patient vital signs and laboratory values at presentation to our institution

Figure 1: (a-d) Axial computed tomography in the lung window demonstrates extensive pneumarthrosis of the left glenohumeral joint with emphysema tracking medially to the posterior scapular musculature.

The patient had a past medical history of Type 2 diabetes mellitus and cerebral autosomal dominant arteriopathy with subcortical infarcts and leukoencephalopathy (CADASIL). CADASIL is a genetic disorder that leads to cognitive decline due to microvascular ischemic changes and large territory cerebral infarcts [13], which, in this patient, led to dysphagia requiring gastrojejunostomy tube placement, aphasia, mutism, quadriplegia, and vascular dementia.

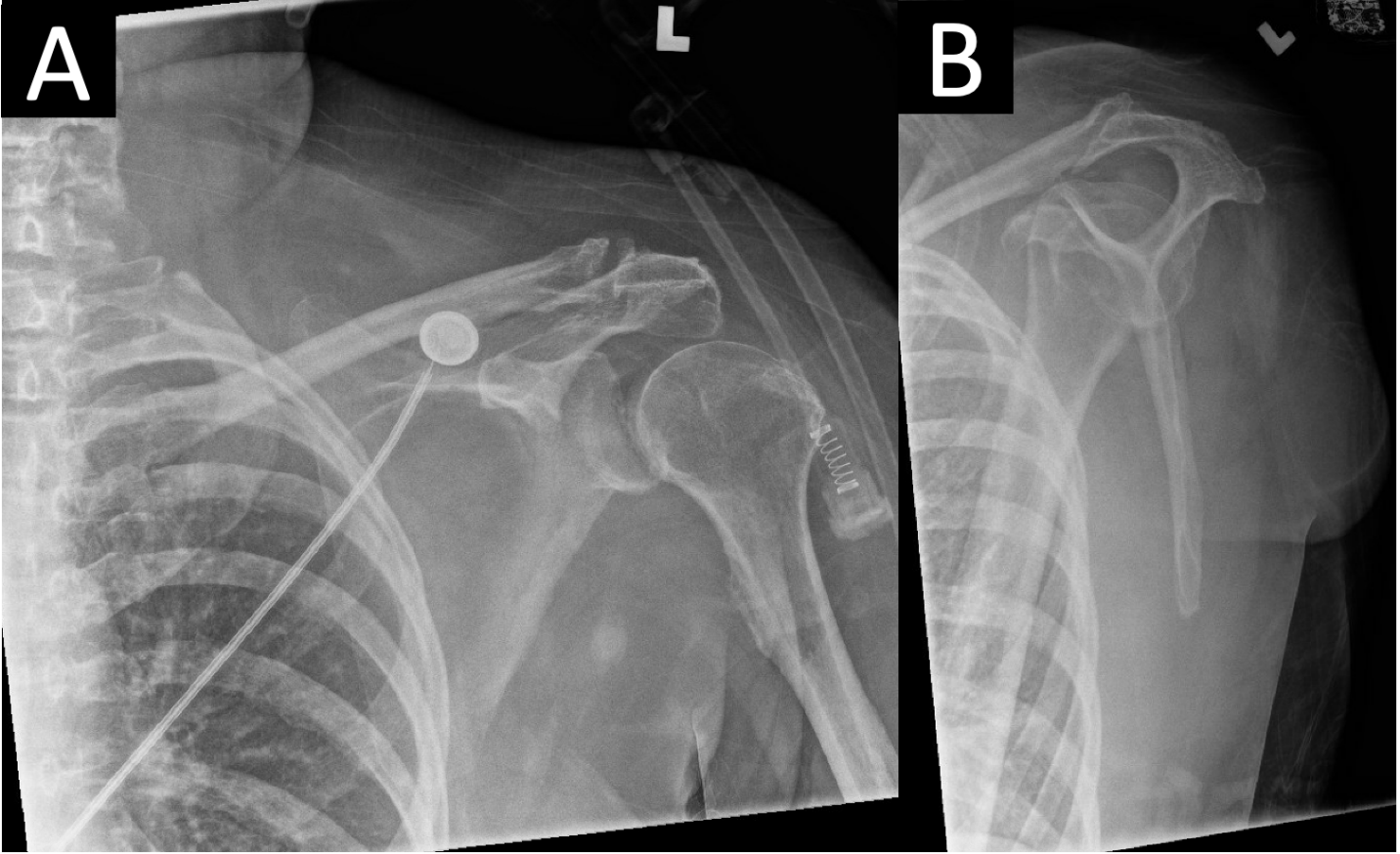

Clinical examination of the left upper extremity was notably benign (Fig. 2) without erythema, bullae, induration, crepitus, or notable wounds. Due to her mental status, sensorimotor examination could not be obtained, but distal pulses were palpable, and passive movement of the extremity did not appear to elicit pain or alter vital signs. Radiographs of the left shoulder revealed pneumarthrosis (Fig. 3a and b).

Figure 2: Clinical photograph of patient’s left shoulder demonstrating no erythema, cellulitis, skin necrosis, wounds, or bullae formation.

Figure 3: (a and b) Anteroposterior(a) and lateral scapula (b)radiographs of the left shoulder revealed a concentric glenohumeral joint with no osseous abnormality or radiopaque foreign body. A small crescent of radiolucency consistent with pneumarthrosis medial to the humeral head is visible in the glenohumeral joint.

CT imaging from the outside hospital demonstrated a needle-like, radiopaque structure passing through the left acromion and terminating in the glenohumeral joint space, likely representing a malpositioned intraosseous vascular access line (Fig. 4a, b, c, d). Further review revealed challenges with vascular access and placement of a left shoulder intraosseous line that was subsequently removed before transfer to our institution. In light of the patient’s clinical examination, the most parsimonious etiology to the intra-articular and deep posterior scapular musculature emphysema was the malpositioned intraosseous line that pierced the acromion process, such that when the line was utilized, products were administered into the left glenohumeral joint, which traveled medially to the scapula due to the intra-articular insertion of the rotator cuff tendons.

Figure 4: (a-d) Outside hospital scout anteroposterior image of patient’s torso (a) demonstrated a radiopaque structure extending cranially from her left shoulder. Sagittal (b) computed tomography (CT) revealed a needle-like, radiopaque structure traveling cranial to caudal and slightly anterior to posterior through the left acromion process and terminating intra-articularly in the left glenohumeral joint superior to the humeral head. Coronal (c) and axial (d) CT confirm intra-articular endpoint in multiple planes.

Left upper extremity NSTI was subsequently excluded as an infectious source following stable and reassuring serial examinations. The ultimate source of sepsis was found to be multifactorial, including her malpositioned gastrojejunostomy tube that was subsequently corrected by interventional radiology, along with pseudomonas pneumonia and UTI which improved with medical . As this patient did not receive any acute orthopaedic intervention, she did not require additional imaging or formal orthopedic follow-up. She was discharged back to her long-term care facility in stable condition 1 month after hospitalization.

NSTI is often a nexus point between critical care, acute care surgery, and orthopedic surgery due to its threat to life and limb caused by the rapid destruction of soft-tissues [7]. NSTI is a rare diagnosis, with an annual incidence of 10 cases/100,000 persons [1]. However, it has been reported to be underestimated in 41–96% of cases [4], largely due to the absence of classic signs – such as bullae, skin necrosis, crepitus, and radiographic emphysema – in over 50% of cases [4,5]. Because NSTI manifests in an extremity in up to 73% of cases [4,7], orthopedic surgery is often the first surgical service consulted. In-hospital mortality remains high, with death in up to 1 in 5 patients with NSTI, which has largely remained unchanged due to the heterogeneity of presentation, challenges of treatment, and limited high-quality evidence [2,3]. Factors associated with poorer outcomes and increased mortality include diabetes, female sex, increased age or comorbidity index, and sepsis at presentation [2,14,15], although up to 26% of patients may have no comorbid risk factors [3]. The most critical factor for improving survival and outcomes in the management of NSTI is the time to surgical exploration and debridement. A recent meta-analysis of 6051 patients with NSTI experienced lower mortality when debridement was performed within 6 hours of presentation [2]. A retrospective study of 295 patients taken for exploration for suspected NSTI revealed a negative exploration rate of 20%; however, the authors advised that surgeons accept this rate of negative exploration to avoid diagnostic delay [16]. In positive cases, rates of amputation are as high as 25% for cases in which debridement alone cannot achieve source control, reconstruction is not possible, or functional status would be superior with amputation [2,7,9]. Factors further associated with limb loss include hypotension at admission, a high glucose level (>300 mg/dL), and a high LRINEC score (>9) [17]. Our case represents a clinical conundrum and diagnostic challenge. Our patient possessed multiple factors associated with poor outcomes, limb loss, and mortality in cases of NSTI [2,13,14,16]. There was overwhelming evidence and precedent in the literature to indicate the patient for operative exploration to exclude NSTI. However, the dissection would have required debridement of the glenohumeral joint, posterior scapular musculature, and chest wall in a critically ill patient, along with a potential forequarter amputation which would have been exceedingly morbid. Although our patient had significant hemodynamic instability and septic shock requiring dual vasopressor support and broad-spectrum antibiotic coverage, laboratory abnormalities, cross-sectional imaging demonstrating deep emphysema, and a LRINEC score of 9, her physical examination was incongruous with NSTI. As demonstrated by our case, it is important to rule out other causes of intra-articular gas before proceeding with surgical exploration. Intra-articular gas or “pneumarthrosis” can be caused by traumatic arthrotomy, closed fracture or dislocation, or prior instrumentation. This patient had no history of recent trauma, and examination of her left upper extremity revealed no apparent wound that would suggest an arthrotomy (Fig. 2). In the absence of penetrating trauma, closed fracture [18,19] or dislocation [20] can cause pneumarthrosis from the vacuum phenomenon of nitrogen gas exchange with distraction or expansion of a closed space [21]. There was no evidence of closed fracture radiographically (Fig. 3a and b), and her glenohumeral joint was concentric on axial CT (Fig. 1a, b, c, d). Finally, prior instrumentation can introduce air into the joint space. After thorough review of outside hospital imaging, it was revealed an intraosseous line was inserted improperly through her acromion process (Fig. 4a, b, c, d), offering a parsimonious, iatrogenic etiology to her pneumarthrosis and deep tissue emphysema. Historically, the proximal tibia has been used for intraosseous access, but the proximal humerus is increasingly favored due to the large volume of the proximal humeral metaphysis that can accommodate higher flow rates [22,23]. Studies evaluating proximal humerus intraosseous access report successful first-pass insertion (>95%) with low complication rates [24,25]. A controlled clinical trial of 29 patients receiving 30 proximal humerus intraosseous lines revealed no major complications and minor complications, including placement failure, poor flow, and catheter dislodgement [23]. However, case reports of adverse events, including a bent intraosseous needle incarcerated in the humeral metaphysis requiring operative removal [26] and iatrogenic humeral anatomic neck fracture [27], have been described.

We add a case to the literature describing improper placement of a proximal humerus intraosseous line through the acromion that led to iatrogenic pneumarthrosis and deep tissue emphysema in the setting of a critically ill patient, causing concern for possible NSTI.

This report helps to remind orthopedic surgeons on call to thoughtfully consider the causes of pneumarthrosis when consulted to rule out NSTI, as they may be the first to evaluate the patient based on anatomic location and hospital policy. A screening tool such as qSOFA, which calculates a score based on mental status, respiratory rate, and systolic blood pressure, is simple to use and provides diagnostic as well as prognostic information. Timely diagnosis and rapid initiation of treatment can make a significant difference in these patients’ clinical course and overall outcome.

References

- 1. May AK, Talisa VB, Wilfret DA, Bulger E, Dankner W, Bernard A, et al. Estimating the impact of necrotizing soft tissue infections in the United States: Incidence and re-admissions. Surg Infect (Lanchmt) 2021;22:509-15. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 2. Nawijn F, Smeeing DP, Houwert RM, Leenen LP, Hietbrink F. Time is of the essence when treating necrotizing soft tissue infections: A systematic review and meta-analysis. World J Emerg Surg 2020;15:4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 3. Hedetoft M, Madsen MB, Madsen LB, Hyldegaard O. Incidence, comorbidity and mortality in patients with necrotising soft-tissue infections, 2005-2018: A Danish nationwide register-based cohort study. BMJ Open 2020;10:e041302. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 4. Goh T, Goh LG, Ang CH, Wong CH. Early diagnosis of necrotizing fasciitis. Br Surg J. 2014;101:e119-25. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 5. Chan T, Yaghoubian A, Rosing D, Kaji A, De Virgilio C. Low sensitivity of physical examination findings in necrotizing soft tissue infection is improved with laboratory values: A prospective study. Am J Surg 2008;196:926-30. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 6. Zacharias N, Velmahos GC, Salama A, Alam HB, De Moya M, King DR, et al. Diagnosis of necrotizing soft tissue infections by computed tomography. Arch Surg 2010;145:452-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 7. McDermott J, Kao LS, Keeley JA, Grigorian A, Neville A, De Virgilio C. Necrotizing soft tissue infections: A review. JAMA Surg 2024;159:1308-15. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 8. Wong CH, Khin LW, Heng KS, Tan KC, Low CO. The LRINEC (laboratory risk indicator for necrotizing fasciitis) score: A tool for distinguishing necrotizing fasciitis from other soft tissue infections. Crit Care Med 2004;32:1535-41. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 9. Schwartz S, Kightlinger E, Virgilio CD, De Virgilio C, De Virgilio M, Kaji A, et al. Predictors of mortality and limb loss in necrotizing soft tissue infections. Am Surg 2013;79:1102-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 10. Fernando SM, Tran A, Cheng W, Rochwerg B, Kyeremanteng K, Seely AJ, et al. Necrotizing soft tissue infection: Diagnostic accuracy of physical examination, imaging, and LRINEC score: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Surg 2019;269:58-65. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 11. Seymour CW, Gesten F, Prescott HC, Friedrich ME, Iwashyna TJ, Phillips GS, et al. Time to treatment and mortality during mandated emergency care for sepsis. N Engl J Med 2017;376:2235-44. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 12. Tarricone A, Mata KD, Gee A, Axman W, Buricea C, Mandato MG, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the effectiveness of LRINEC score for predicting upper and lower extremity necrotizing fasciitis. J Foot Ankle Surg 2022;61:384-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 13. Geng Y, Cai C, Li H, Zhou Q, Wang M, Kang H. Short-term frequently relapsing ischemic strokes followed by rapidly progressive dementia in CADASIL: A case report and literature review. Neurologist 2024;30:182-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 14. Krieg A, Dizdar L, Verde PE, Knoefel WT. Predictors of mortality for necrotizing soft-tissue infections: A retrospective analysis of 64 cases. Langenbecks Arch Surg 2014;399:333-41. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 15. Anaya DA, McMahon K, Nathens AB, Sullivan SR, Foy H, Bulger E. Predictors of mortality and limb loss in necrotizing soft tissue infections. Arch Surg 2005;140:151-7; discussion 158. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 16. Howell EC, Keeley JA, Kaji AH, Deane MR, Kim DY, Putnam B, et al. Chance to cut: Defining a negative exploration rate in patients with suspected necrotizing soft tissue infection. Trauma Surg Acute Care Open 2019;4:e000264. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 17. Park HG, Yang JH, Park BH, Yi HS. Necrotizing soft-tissue infections: A retrospective review of predictive factors for limb loss. Clin Orthop Surg 2022;14:297-309. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 18. Noble T, Romeo NM, LeBrun CT, DiPasquale T. Incidence of vacuum phenomenon related intra-articular or subfascial gas found on computer-assisted tomography (CT) scans of closed lower extremity fractures. J Orthop Trauma 2017;31:e381-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 19. Smith TJ, Judice A, Forte S, Boniello M, Kleiner M, Fuller D. The vacuum phenomenon in the elbow: A case report. JBJS Case Connect 2020;10:e20.00203:1-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 20. Fairbairn KJ, Mulligan ME, Murphey MD, Resnik CS. Gas bubbles in the hip joint on CT: An indication of recent dislocation. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1995;164:931-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 21. Nagarajan K, Mishra P, Velagada S, Tripathy SK. The air inside joint: A sign of disease pathology or a benign condition? Cureus 2020;12:e8479. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 22. Warren DW, Kissoon N, Sommerauer JF, Rieder MJ. Comparison of fluid infusion rates among peripheral intravenous and humerus, femur, malleolus, and tibial intraosseous sites in normovolemic and hypovolemic piglets. Ann Emerg Med 1993;22:183-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 23. Paxton JH, Knuth TE, Klausner HA. Proximal humerus intraosseous infusion: A preferred emergency venous access. J Trauma 2009;67:606-11. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 24. Philbeck TE, Puga TA, Montez DF, Davlantes C, DeNoia EP, Miller LJ. Intraosseous vascular access using the EZ-IO can be safely maintained in the adult proximal humerus and proximal tibia for up to 48 h: Report of a clinical study. J Vasc Access 2022;23:339-47. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 25. Wampler D, Schwartz D, Shumaker J, Bolleter S, Beckett R, Manifold C. Paramedics successfully perform humeral EZ-IO intraosseous access in adult out-of-hospital cardiac arrest patients. Am J Emerg Med 2012;30:1095-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 26. Krishnan M, Lester K, Johnson A, Bardeloza K, Edemekong P, Berim I. Bent metal in a bone: A rare complication of an emergent procedure or a deficiency in skill set? Case Rep Crit Care 2016;2016:4382481. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 27. Hopp AC, Long JR, Fox MG, Flug JA. Iatrogenic humeral anatomic neck fracture after intraosseous vascular access. Skeletal Radiol 2020;49:1481-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]