Musculoskeletal occupational injury prevalence among Indian orthopedic surgeons is alarmingly high, largely due to professional demands and ergonomic challenges. Targeted interventions such as ergonomic modifications, awareness initiatives, and weight management programs are crucial to reduce injuries and safeguard surgeons’ well being.

Dr. Madhan Jeyaraman, Department of Orthopaedics, ACS Medical College and Hospital, Dr MGR Educational and Research Institute, Chennai, Tamil Nadu, India. E-mail: madhanjeyaraman@gmail.com

Introduction: Orthopedic surgeons are frequently exposed to musculoskeletal occupational injuries (MSOI) due to the demanding physical nature of their profession. This study aims to analyze the risk factors contributing to MSOI, evaluate their impact on surgeons' health and productivity, and explore preventive measures to mitigate injury severity.

Objective: To identify key risk factors associated with MSOI among orthopedic surgeons in Tamil Nadu and assess their influence on career longevity and surgical practice.

Materials and Methods: A cross-sectional survey targeting 5000 orthopedic surgeons achieved a response rate of 15.84% (n = 792). Data encompassed demographic variables, practice characteristics, injury prevalence, and severity scores. Associations between risk factors and injury severity were statistically analyzed.

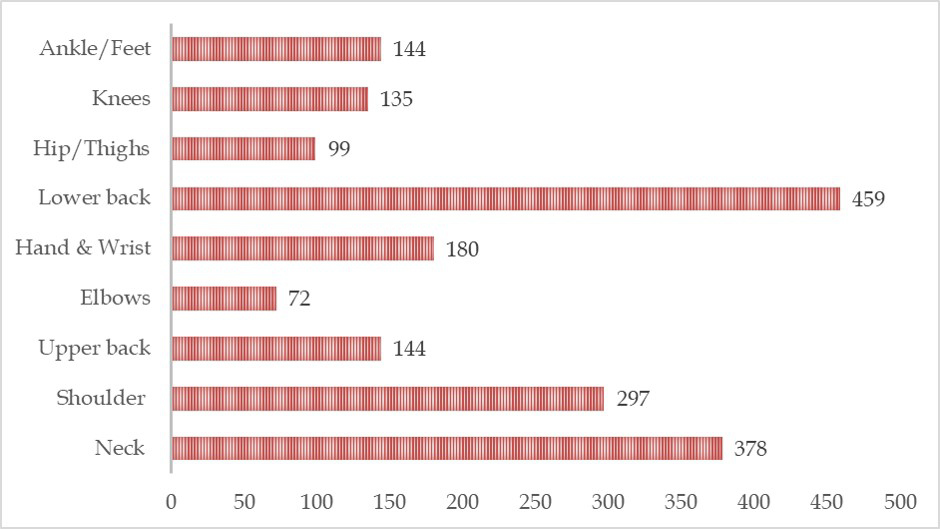

Results: Significant correlations were observed between MSOI severity and risk factors, including weight, years of practice, multiple subspecialties, operating position, lack of visual aids, and lead apron usage. The lower back (58%) and neck (47.7%) were the most affected regions. Despite prevalent injuries, only 13.6% received treatment, predominantly physiotherapy.

Conclusion: MSOI prevalence among Indian orthopedic surgeons is alarmingly high, driven by professional demands and ergonomic challenges. Targeted interventions, including ergonomic modifications, awareness campaigns, and weight management programs, are essential to reduce injury rates and support surgeons' well-being.

Keywords: Musculoskeletal injury, orthopedic surgery, occupational hazards, ergonomic practices, surgeon health.

Occupational injuries, as defined by the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA), result from incidents in the work environment that harm the body or aggravate pre-existing conditions [1,2]. Among healthcare professionals, surgeons, particularly those in orthopedic specialties, face a unique interplay of occupational hazards, such as radiation exposure, chemical toxicity, psychological stress, and musculoskeletal (MSK) injuries [2,3]. These hazards contribute significantly to their professional and personal health burdens, often compounding over time. Radiation exposure, for instance, has been linked to a striking 25-fold increase in thyroid cancer incidence among spine surgeons, underlining the long-term risks they endure [4]. Similarly, the toxic properties of Polymethylmethacrylate cement, a material commonly utilized in orthopedic procedures since the 1950s, pose threats to the skin, respiratory system, and nervous system [5]. Another pervasive risk stems from electrocautery smoke, with its harmful effects reportedly exceeding those of second-hand smoking [6]. Psychological stress, exacerbated by demanding schedules and insufficient sleep, further undermines the emotional well-being of surgeons [7,8]. While these risks paint a concerning picture, MSK injuries remain the most prevalent occupational hazard for orthopedic surgeons [2,9,10]. Chronic exposure to non-ergonomic working conditions – characterized by prolonged standing, repetitive movements, and sustained awkward postures – places undue strain on their bones and muscles [3]. Despite their resilience and athlete-like work ethic, orthopedic surgeons are particularly vulnerable to overuse injuries, which are often exacerbated by the physical demands of their profession [11]. Alarmingly, studies indicate that orthopedic surgeons face a significantly higher risk of work-related injuries compared to other surgical specialties [12]. Efforts to mitigate these risks have led to the establishment of ergonomic guidelines for operating environments [13,14,15,16]. However, challenges, such as insufficient awareness [17,18,19] and difficulties in implementation [19] limit their effectiveness. This necessitates a deeper understanding of the specific occupational risks faced by different populations and subspecialties, including orthopedic surgeons, to tailor preventive strategies effectively. To date, limited research has been conducted to examine the prevalence of musculoskeletal occupational injuries (MSOI) among orthopedic surgeons. Given the potential influence of ethnic and regional differences on the occurrence and severity of MSOI, this study aims to address this gap. By investigating risk factors contributing to MSOI among orthopedic surgeons, this research seeks to provide critical insights that can inform both clinical practice and occupational safety protocols.

We invited 5000 members of the Tamil Nadu Orthopedic Association through the official social network group of the association to answer an anonymous web-based survey. The invitation mentioned that the study would be used to evaluate the impact of MSOIs among orthopedic surgeons on their surgical practice. No incentives were offered to the participants. Two reminders, apart from the original invite, were sent over 8 weeks to request participation from non-respondents. Previously developed surveys to evaluate physician injury were cross-referenced to develop a 25-item, web-based survey administered through Google Forms. Simple, direct questions were used to minimize the respondent burden. The survey consisted of 3 sets of questions to be answered. First, demographic data, such as age, hand dominance, working hours, and years in orthopedic practice, were obtained. The second set consisted of the Nordic MSK questionnaire to assess the MSK disorder in various regions of the body and the treatment undergone for the same. The final set included the assessment of the impact of these injuries on their surgical practice. The questionnaire presented to the respondents is given in Supplementary File 1. We used the statistical software Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) 25.0 (IBM SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL) to perform descriptive statistics. Fisher’s exact tests and analysis of variance tests were used to determine the significant associations between various factors that contributed to MSOIs. A P < 0.05 was considered significant.

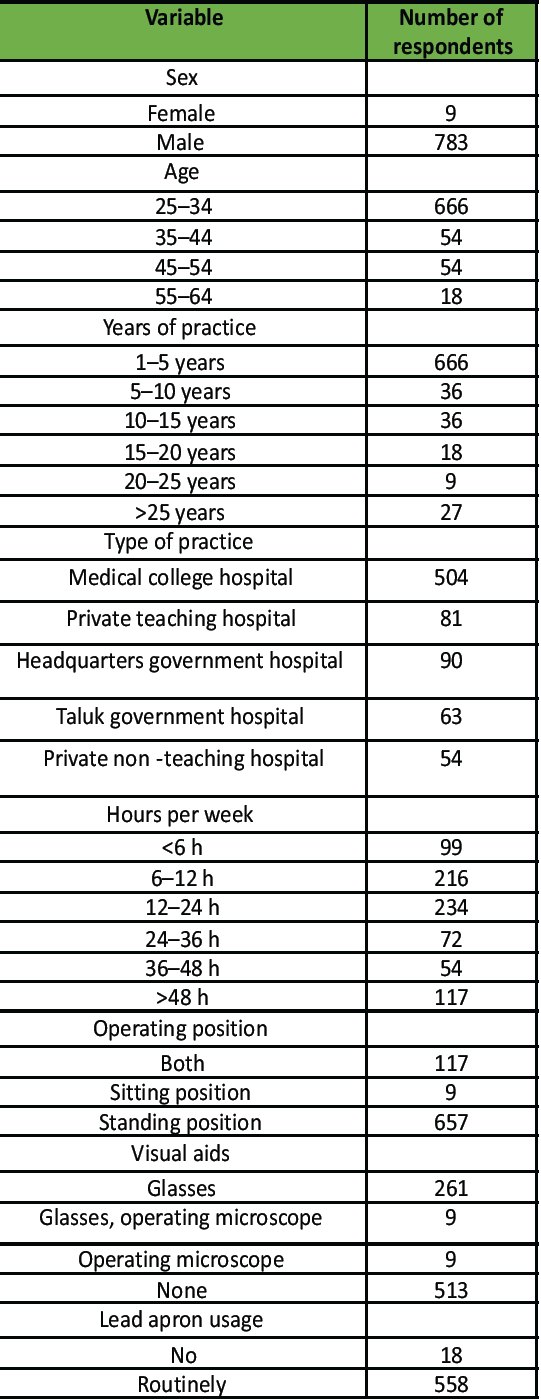

A total of 5000 orthopedic surgeons were invited to participate in the survey, with 15.84% (n = 792) completing it during the data collection period. The respondents had a mean age of 31.4 years (±7.2), with the overwhelming majority being male (98.9%, n = 783), while only 1.1% (n = 9) were female, as shown in Table 1.

Table 1: Demographic data of the participants, part of the first set of questions in the survey

Most of the participants were right-hand dominant (97.7%, n = 774), whereas a small percentage (2.3%, n = 18) were left-hand dominant, highlighting demographic variations among the surveyed population. Professionally, a significant proportion of respondents (84.1%, n = 666) were early-career surgeons with <5 years of practice, while 11.3% (n = 90) were established professionals with over a decade of experience. Regarding workplace settings, teaching institutions employed the majority (73.8%, n = 585), followed by non-teaching government facilities (19.4%, n = 153) and private institutions (6.8%, n = 54), illustrating a diverse distribution of practice environments. The survey represented a broad range of orthopedic subspecialties, with 33% (n = 261) of surgeons specializing in a single domain and others working across multiple subspecialties, including trauma surgery, arthroplasty, spine surgery, arthroscopy, pediatric orthopedics, orthopedic oncology, and hand surgery. The weekly surgical workload of respondents varied significantly, with 39.8% (n = 315) performing limited surgeries (<12 h/week) and 21.6% (n = 171) engaged in high-volume procedures (>36 h/week). Most surgeons (83%, n = 657) operated exclusively in a standing position, whereas a smaller proportion (14.8%) alternated between sitting and standing during surgeries. In addition, routine use of lead aprons during procedures was reported by 70.5% (n = 558), emphasizing radiation safety as a noteworthy concern among the respondents. The distribution of MSOI is presented in Fig. 1.

Figure 1: Regional distribution of musculoskeletal occupational injury among the survey respondents.

Although 85.2% of surgeons reported injuries in at least one anatomical region, only 13.6% (n = 108) sought treatment, predominantly physiotherapy (86.4%). A smaller proportion, 6.8% (n = 54), required work absences due to injury. Among respondents, 17% (n = 135) reduced their surgical workload during recovery, while 19.3% (n = 153) reported that injuries interfered with daily activities. Alarmingly, 27.3% (n = 216) experienced injuries during the survey’s prior week, and 52.3% (n = 414) attributed injuries to their professional responsibilities. In addition, 37.5% (n = 297) believed their ailments would have a lasting impact on career performance.

Based on the results from the Nordic MSK questionnaire used to evaluate the impact of the MSK injuries reported in the study, we noted the severity of the noted involvement significantly correlated to weight (r = 0.181, P = 0.017), years of practice (r = −0.108, P = 0.002), practice location (r = 0.142, P < 0.001), cumulative operating hours per week (r = 0.149, P < 0.001), number of practicing sub-specialties (r = 0.122, P = 0.004), usage of visual aids (r = −0.073, P = 0.040), lead apron usage (r = −0.121, P = 0.001). We conducted logistic regression to identify the risk factors making a significant contribution to the severity of the MSK injuries. Factors, such as weight (P < 0.001), years of practice (P = 0.001), number of practicing sub-specialties (P = 0.004), operating position (P < 0.001), lack of visual aids (P = 0.001), and routine use of lead apron (P < 0.001) to significantly responsible for the severity of the scores noted among the survey respondents.

The findings of this study underscore the significant burden of MSOI among orthopedic surgeons, with an overwhelming 85.2% reporting at least one such injury during their practice. Notably, 13.6% of respondents required treatment, and 6.8% necessitated time off due to injury, reflecting the critical occupational hazards these surgeons face within the surgical environment [2,12]. The high prevalence rates indicate an urgent need for systemic measures to mitigate these risks and enhance the overall well-being of surgeons. The severity of MSOI among orthopedic surgeons is influenced by a range of interconnected risk factors, which reflect both personal attributes and professional circumstances [20]. This study has identified several factors significantly responsible for the scores noted among survey respondents, including weight, years of practice, number of practicing subspecialties, operating positions, lack of visual aids, and the routine use of lead aprons during procedures. Surgeon-specific attributes, such as body weight, play a critical role in determining the severity of MSOI [21,22]. When coupled with prolonged hours of standing during surgeries, excess weight places undue strain on the MSK system, particularly affecting the lower back and neck regions. This correlation underscores the importance of weight management as an early and proactive intervention to reduce MSOI incidence and severity. Weight reduction not only contributes to better overall health but also alleviates the physical burden on surgeons during long operating hours. By addressing this modifiable risk factor, surgeons can potentially enhance their endurance and mitigate occupational injuries. Professional practice factors also contribute significantly to MSOI severity. The cumulative years of practice in orthopedic surgery are associated with an increased risk of injury, as the repetitive demands of the profession lead to chronic MSK strain [23,24,25]. Furthermore, the combination of multiple subspecialties – such as arthroplasty, spine surgery, and trauma surgery – into a single practice amplifies the physical challenges faced by surgeons. These subspecialties often involve intricate procedures requiring sustained awkward postures and repetitive movements, which cumulatively exacerbate the risk of MSOI. Strategies aimed at balancing subspecialty workloads and incorporating ergonomic modifications can help reduce the long-term impact of these practice factors. Operating room ergonomics, including the use of visual aids, have emerged as critical elements in addressing MSOI severity [26]. The lack of adequate visual aids during surgeries places additional strain on surgeons, forcing them to adopt suboptimal postures to maintain focus and precision. The integration of advanced visual technologies, such as high-definition monitors and magnification devices, can significantly improve surgical ergonomics by enabling surgeons to work comfortably without compromising accuracy. In addition, ensuring comfortable operating positions, such as alternating between sitting and standing during procedures, can reduce physical fatigue and distribute MSK stress more evenly [27,28,29]. Specialties that involve the routine use of intraoperative fluoroscopy introduce another layer of risk, as surgeons are required to wear lead aprons to shield themselves from radiation exposure [30,31,32]. While essential for safety, these aprons contribute to additional weight and strain on the MSK system, particularly during extended procedures. This study highlights the need for innovative approaches to minimize the physical burden associated with lead apron usage. Solutions, such as lightweight protective materials or alternative shielding techniques could enhance surgeons’ comfort while maintaining radiation safety standards. Collectively, these risk factors emphasize the multifaceted nature of MSOI among orthopedic surgeons. By addressing individual surgeon attributes, optimizing professional practices, and enhancing operating room ergonomics, significant strides can be made in reducing the incidence and severity of MSOI. Institutions and professional organizations must prioritize ergonomic training, develop targeted interventions, and promote awareness to safeguard the health and sustainability of the surgical workforce [33,34]. The prevalence of MSOI is not uniform across subspecialties, as evidenced by studies on orthopedic surgeons specializing in trauma surgery, spine surgery, arthroplasty, hand surgery, pediatric orthopedics, and oncology. Subspecialty-specific variations in surgical techniques, tools, and patient demographics may contribute to the differing injury rates reported in the literature. Furthermore, gender-specific studies and investigations involving orthopedic residents have shed light on unique risk factors within these populations. Despite the diversity of study cohorts, this investigation is the first to evaluate MSOI among orthopedic surgeons in the Indian subcontinent, offering valuable insights into regional occupational health challenges [2,35,36,37,38,39,40]. Operating room ergonomics, workflow inefficiencies, and surgical equipment are critical contributors to the high MSOI rates observed in this study. Poor ergonomic practices have been extensively documented in the literature as a major factor influencing injury prevalence among surgeons [11,12,36,19,41,42]. A lack of awareness regarding proper ergonomic techniques further exacerbates the issue. Buddle et al., reported that only 43.6% of respondents were aware of operating room ergonomics, and even fewer (30.9%) implemented changes to optimize their working environment. This gap in knowledge and practice underscores the importance of integrating ergonomics education into surgical training and professional development programs [43]. The benefits of strength training and ergonomic interventions in reducing MSOI risk have been highlighted in several studies. Dairywala et al., for instance, proposed targeted interventions for cardiothoracic surgeons, who also face high rates of work-related MSK conditions. Adapting similar strategies for orthopedic surgeons could help mitigate the occupational hazards associated with their demanding work environments. Awareness campaigns, institutional support, and ergonomic optimization of operating rooms are critical components of a comprehensive approach to injury prevention [35]. The long-term implications of MSOI extend beyond physical discomfort, affecting surgeons’ professional performance and career longevity. The findings of this study reveal that 19.3% of respondents experienced disruptions in daily activities due to injuries, while 37.5% believed their ailments would have a lasting impact on their career performance. In addition, 17% reported reducing their surgical workloads to accommodate injury recovery. These statistics highlight the profound impact of MSOI on surgeons’ productivity and quality of life, emphasizing the need for proactive measures to address this occupational health challenge [2]. This study is a significant contribution to the existing body of literature on occupational injuries in orthopedic practice, providing novel insights into the prevalence and impact of MSOI among Indian surgeons. By building on the findings of previous research and addressing region-specific challenges, this investigation lays the groundwork for future studies and interventions. Collaborative efforts between healthcare institutions, professional organizations, and policymakers are essential to promote ergonomic practices, enhance awareness, and provide resources for injury prevention and management. Ultimately, addressing MSOI requires a multifaceted approach that integrates education, institutional support, and policy reform. By prioritizing the well-being of surgeons, such initiatives not only safeguard individual health but also ensure the sustainability and efficiency of the surgical workforce. As orthopedic surgery continues to evolve, mitigating occupational hazards must remain a priority to achieve these broader objectives [2,9,10,11,12,35,36,37,39,42,43,44,19,44]. There are several limitations to our study. First, it is based on self-reported measures whose validity and reliability have not been fully established. Physician reports of injuries and the consequences of these injuries may include errors because of recall bias. Furthermore, respondents may be biased to report a higher number of injuries to draw attention to the issue of physician wellness. Conversely, physicians may have underreported injuries because of the culture of providing optimal treatment to patients regardless of their health. We suggest that future studies examining physician injury include questions about the nature of reported injuries (e.g., lacerations, fractures, or sprains). Surgeons were asked to report a single subspecialty, although many surgeons work across different subspecialties, so subspecialty-specific data should be interpreted with caution. Future surveys should add a category of “no pain” to the question involving the frequency of pain. Response bias may be present, as only 15.8% have responded. This study targeted only orthopedic surgeons who were currently practicing, so it may have underestimated the prevalence of injury because of the healthy worker effect. It may also underestimate the lost productivity resulting from workplace injury, as the performance of fewer procedures during recovery from injury was not captured in the survey. Estimation of the national prevalence of surgeon injury based on this statewide study should be conducted with caution.

The critical impact of MSOI among orthopedic surgeons reflects an urgent need for interventions addressing weight management, ergonomic practices, and institutional support. With lower back and neck injuries being notably prevalent, multifaceted preventive measures can alleviate the physical strain faced by surgeons while ensuring sustainable career longevity and enhanced productivity. By bridging gaps in awareness, implementing advanced visual technologies, and fostering supportive environments, the findings pave the way for improved occupational safety, benefiting both surgeons and patient care outcomes.

1. MSOI prevalence is alarmingly high among orthopedic surgeons, with lower back and neck most affected, significantly impacting health, productivity, and career longevity.

2. Key risk factors include surgeon weight, years of practice, multiple subspecialties, operating position, lack of visual aids, and routine lead apron usage.

3. Ergonomic challenges such as prolonged standing, awkward postures, and absence of supportive aids strongly contribute to musculoskeletal injury severity in orthopedic practice.

4. Treatment-seeking behavior is low (13.6%), predominantly only physiotherapy, despite widespread injury burden.

5. Targeted interventions such as ergonomic modifications, awareness campaigns, and weight management programs are essential to reduce injury rates and safeguard surgeons’ well-being.

References

- 1. 1904.5 – Determination of Work-Relatedness. Occupational Safety and Health Administration. Available from: https://www.osha.gov/laws/regs/regulations/standardnumber/1904/1904.5 [Last accessed on 2025 May 01]. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 2. AlQahtani SM, Alzahrani MM, Harvey EJ. Prevalence of musculoskeletal disorders among orthopedic trauma surgeons: An OTA survey. Can J Surg 2016;59:42-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 3. Lester JD, Hsu S, Ahmad CS. Occupational hazards facing orthopedic surgeons. Am J Orthop (Belle Mead NJ) 2012;41:132-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 4. Wagner TA, Lai SM, Asher MA. SRS surgeon members’ risk for thyroid cancer: Is it increased? Spine J Meeting Abstracts 2006;:44: DOI: 10.1097/01.brs.0000317584.05613.4e. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

- 5. Leggat PA, Smith DR, Kedjarune U. Surgical applications of methyl methacrylate: A review of toxicity. Arch Environ Occup Health 2009;64:207-12. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 6. Zhou YZ, Wang CQ, Zhou MH, Li ZY, Chen D, Lian AL, et al. Surgical smoke: A hidden killer in the operating room. Asian J Surg 2023;46:3447-54. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 7. Small GW. House officer stress syndrome. Psychosomatics 1981;22:860-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 8. Sargent MC, Sotile W, Sotile MO, Rubash H, Barrack RL. Quality of life during orthopaedic training and academic practice. Part 1: Orthopaedic surgery residents and faculty. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2009;91:2395-405. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 9. Davis WT, Sathiyakumar V, Jahangir AA, Obremskey WT, Sethi MK. Occupational injury among orthopaedic surgeons. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2013;95:e107. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 10. Auerbach JD, Weidner ZD, Milby AH, Diab M, Lonner BS. Musculoskeletal disorders among spine surgeons: Results of a survey of the scoliosis research society membership. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2011;36:E1715-21. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 11. Vasireddi N, Vasireddi N, Shah AK, Moyal AJ, Gausden EB, Mclawhorn AS, et al. High prevalence of work-related musculoskeletal disorders and limited evidence-based ergonomics in orthopaedic surgery: A systematic review. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2024;482:659-71. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 12. Aaron KA, Vaughan J, Gupta R, Ali NE, Beth AH, Moore JM, et al. The risk of ergonomic injury across surgical specialties. PLoS One 2021;16:e0244868. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 13. Cardenas-Trowers O, Kjellsson K, Hatch K. Ergonomics: Making the OR a comfortable place. Int Urogynecol J 2018;29:1065-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 14. Rosenblatt PL, McKinney J, Adams SR. Ergonomics in the operating room: Protecting the surgeon. J Minim Invasive Gynecol 2013;20:744. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 15. Craven R, Franasiak J, Mosaly P, Gehrig PA. Ergonomic deficits in robotic gynecologic oncology surgery: A need for intervention. J Minim Invasive Gynecol 2013;20:648-55. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 16. Seagull FJ. Disparities between industrial and surgical ergonomics. Work 2012;41 Suppl 1:4669-72. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 17. Franasiak J, Craven R, Mosaly P, Gehrig PA. Feasibility and acceptance of a robotic surgery ergonomic training program. JSLS 2014;18:e2014.00166. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 18. Welcker K, Kesieme EB, Internullo E, Kranenburg Van Koppen LJ. Ergonomics in thoracoscopic surgery: Results of a survey among thoracic surgeons. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg 2012;15:197-200. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 19. Park A, Lee G, Seagull FJ, Meenaghan N, Dexter D. Patients benefit while surgeons suffer: An impending epidemic. J Am Coll Surg 2010;210:306-13. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 20. Swank KR, Furness JE, Baker E, Gehrke CK, Rohde R. A survey of musculoskeletal disorders in the orthopaedic surgeon: Identifying injuries, exacerbating workplace factors, and treatment patterns in the orthopaedic community. J Am Acad Orthop Surg Glob Res Rev 2022;6:e20.00244. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 21. Tan KS, Kwek EB. Musculoskeletal occupational injuries in orthopaedic surgeons and residents. Malays Orthop J 2020;14:24-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 22. Schlussel AT, Maykel JA. Ergonomics and musculoskeletal health of the surgeon. Clin Colon Rectal Surg 2019;32:424-34. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 23. Richard J, Cho S, Journeay WS. Work-related musculoskeletal pain among orthopaedic surgeons: A systematic literature search and narrative synthesis. J Clin Orthop Trauma 2025;66:102984. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 24. McQuivey KS, Christopher ZK, Deckey DG, Mi L, Bingham JS, Spangehl MJ. Surgical ergonomics and musculoskeletal pain in arthroplasty surgeons. J Arthroplasty 2021;36:3781-7.e7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 25. Rață AL, Barac S, Garleanu LL, Onofrei RR. Work-related musculoskeletal complaints in surgeons. Healthcare (Basel) 2021;9:1482. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 26. Janki S, Mulder EE, IJzermans JN, Tran TC. Ergonomics in the operating room. Surg Endosc 2017;31:2457-66. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 27. Abdollahi T, Pedram Razi S, Pahlevan D, Yekaninejad MS, Amaniyan S, Leibold Sieloff C, et al. Effect of an ergonomics educational program on musculoskeletal disorders in nursing staff working in the operating room: A quasi-randomized controlled clinical trial. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020;17:7333. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 28. Hoe VC, Urquhart DM, Kelsall HL, Zamri EN, Sim MR. Ergonomic interventions for preventing work‐related musculoskeletal disorders of the upper limb and neck among office workers. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2018;10:CD008570. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 29. Liu F, Duan Y, Wang Z, Ling R, Xu Q, Sun J, et al. Mixed adverse ergonomic factors exposure in relation to work-related musculoskeletal disorders: A multicenter cross-sectional study of Chinese medical personnel. Sci Rep 2025;15:14705. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 30. Rashid MS, Aziz S, Haydar S, Fleming SS, Datta A. Intra-operative fluoroscopic radiation exposure in orthopaedic trauma theatre. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol 2018;28:9-14. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 31. Jenkins NW, Parrish JM, Sheha ED, Singh K. Intraoperative risks of radiation exposure for the surgeon and patient. Ann Transl Med 2021;9:84. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 32. Agarwal A. Radiation risk in orthopedic surgery: Ways to protect yourself and the patient. Oper Tech Sports Med 2011;19:220-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 33. Mahmud N, Kenny DT, Zein R, Hassan SN. Ergonomic training reduces musculoskeletal disorders among office workers: Results from the 6-month follow-up. Malays J Med Sci 2011;18:16-26. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 34. Lee MJ, Wang CJ, Chang JH. Effectiveness of an ergonomic training with exercise program for work-related musculoskeletal disorders among hemodialysis nurses: A pilot randomized control trial. J Saf Res 2024;91:481-91. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 35. Dairywala MI, Gupta S, Salna M, Nguyen TC. Surgeon strength: Ergonomics and strength training in cardiothoracic surgery. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2022;34:1220-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 36. Tarabishy S, Brown G, Hudson HT, Herrera FA. Fixing hands, breaking backs: The ergonomics and physical detriment of the hand surgeon. Hand (NY) 2024;19:509-15. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 37. Alsiddiky AM, Alatassi R, Altamimi SM, Alqarni MM, Alfayez SM. Occupational injuries among pediatric orthopedic surgeons: How serious is the problem? Medicine (Baltimore) 2017;96:e7194. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 38. Knudsen ML, Ludewig PM, Braman JP. Musculoskeletal pain in resident orthopaedic surgeons: Results of a novel survey. Iowa Orthop J 2014;34:190-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 39. AlHussain A, Almagushi NA, Almosa MS, Alotaibi SN, AlHarbi K, Alharbi AM, et al. Work-related shoulder pain among Saudi orthopedic surgeons: A cross-sectional study. Cureus 2023;15:e48023. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 40. Clar C, Koutp A, Leithner A, Leitner L, Puchwein P, Vielgut I, et al. Occupational injuries in orthopedic and trauma surgeons in Austria. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2024;144:1171-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 41. Shah M, Gross K, Wang C, Kurlansky P, Krishnamoorthy S. Working through the pain: A cross-sectional survey on musculoskeletal pain among surgeons and residents. J Surg Res 2024;293:335-40. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 42. Alaqeel M, Tanzer M. Improving ergonomics in the operating room for orthopaedic surgeons in order to reduce work-related musculoskeletal injuries. Ann Med Surg (Lond) 2020;56:133-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 43. Buddle V, Nugent R, Jack RA, DeLuca P. Orthopedists report high prevalence of work-related pain and low ergonomic awareness. Orthopedics 2023;46:280-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 44. Yakkanti RR, Sedani AB, Syros A, Aiyer AA, D’Apuzzo MR, Hernandez VH. Prevalence and spectrum of occupational injury among orthopaedic surgeons: A cross-sectional study. JB JS Open Access 2023;8:e22.00083. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]