The patient-controlled opioid-free surgery program (PCOFSP) demonstrates that total hip arthroplasty can be successfully performed without opioids through a patient-specific, multidisciplinary approach that addresses both the physical and the psychological aspects of pain.

Dr. Jacques E. Chelly, Department of Anesthesiology and Perioperative Medicine, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA, USA. E-mail: chelje@anes.upmc.edu

Introduction: Total hip arthroplasty (THA) is a procedure widely used to relieve pain and restore mobility in patients with hip joint disorders such as osteoarthritis. Traditionally, post-operative pain management has depended on opioids. However, growing concerns about opioid-related side effects and the risk of long-term opioid dependence have led to an increased interest in opioid-sparing approaches. Although regional anesthesia and non-opioid pharmacologic options show promise, studies report that opioid-free anesthesia is achieved in only 46.7% and 12% of cases, respectively. With a rising number of patients expressing a desire to avoid opioids due to fear of addiction, our team developed a patient-controlled opioid-free surgical pathway (PCOFSP). This pathway is based on a patient-specific, multidisciplinary approach that includes care coordination across the perioperative team, targeted education for patients and staff, patient identification on the day of surgery facilitated by opioid-free wristbands and chart labels, and a special order set ensuring the use of non-opioid analgesics with multimodal care, regional anesthesia, and complementary techniques. Each care plan is personalized to address both the physical and the emotional aspects of pain.

Case Report: A 67-year-old Caucasian male with bilateral hip osteoarthritis elected to undergo a left THA, followed 5 months later by a right THA. On both occasions, he declined the use of opioids. Initially, the patient was not identified for the PCOFSP because the surgeon had not agreed to the regional anesthesia program requirement. After the patient firmly requested an opioid-free experience and the surgeon agreed to regional anesthesia, he was enrolled. For his left THA, the patient used mindful breathing, ice therapy, and aromatherapy with Elequil Aromatabs® Lavender-Peppermint (Beekley Corporation, Bristol, CT). For the right THA, although regional anesthesia was not requested, the patient again refused opioids. The surgical and acute pain teams collaborated, and the nurse practitioner developed a personalized care plan, incorporating mindful breathing, aromatherapy, NeuroCuple™ patches (nCap Medical LLC, Heber City, UT), and lidocaine patches.

Conclusion: This case illustrates that the PCOFSP can enable patients to successfully undergo opioid-free THA. Although patients can choose different complementary techniques for each surgery, the proposed multidisciplinary and multimodal approach represents an effective strategy.

Keywords: Opioid, opioid-free, hypnosis, acupuncture, auriculotherapy, nanotechnology, acute pain, surgery.

Total hip arthroplasty (THA) is a common surgery aimed at alleviating pain and restoring function in patients with hip joint disorders such as osteoarthritis [1]. Traditionally, post-operative pain management for THA has relied on opioids [2]. While effective, opioids are associated with adverse side effects, including respiratory depression, nausea, vomiting, and a substantial risk of long-term dependence [3,4,5]. Increasing concerns surrounding these adverse effects, combined with a growing public and clinical interest in reducing opioid reliance, have prompted the development of alternative perioperative strategies. In this context, opioid-free surgical models have emerged as an innovative response to the opioid crisis [6,7,8,9,10,11]. Emerging evidence supports the feasibility of opioid-free anesthesia using multimodal approaches, including regional anesthesia, acetaminophen, non-steroidal anti-inflammatories, gabapentinoids, ketamine, and lidocaine [6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19]. Regional anesthesia has been shown to reduce intraoperative opioid requirements and improve early post-operative pain control, though studies report variable success in completely eliminating opioid use, with opioid-free anesthesia achieved in only 46.7% of cases with regional techniques and 12% using multimodal pharmacologic protocols alone [8,20]. These findings highlight the limitations of pharmacologic strategies in addressing both the physiological and psychological components of pain, reinforcing the need for complementary, patient-centered approaches. Complementary interventions such as mindfulness-based techniques, aromatherapy, music therapy, hypnosis, acupuncture, auriculotherapy, and emerging technologies such as nanotechnology-based patches have demonstrated efficacy in reducing perioperative pain and anxiety [21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30]. For example, mindful breathing and guided relaxation can reduce sympathetic activation and improve pain tolerance [21], while aromatherapy and music therapy provide sensory distraction and promote relaxation, contributing to reductions in perceived pain and post-operative opioid requirements [22,26]. Auriculotherapy and acupuncture have also shown promising results for prolonged pain control and anxiety management [23,25,29], and devices such as the NeuroCuple™ patch offer adjunctive pain relief through localized nanotechnology-based modulation of inflammation and nociceptive signaling [27]. Psychological comorbidities, including anxiety and mood disorders, are associated with increased post-operative pain and higher opioid consumption [31,32]. Interventions that address both psychological and physical pain have demonstrated synergistic benefits, improving recovery outcomes and patient satisfaction [28,33]. Patient engagement and shared decision-making are critical factors in successful opioid-free pathways, enabling patients to select tailored strategies and enhancing adherence to non-opioid pain management plans [34,35]. Digital cognitive-behavioral tools, such as RxWell, have been integrated into perioperative care to further support patients’ psychological preparedness and resilience [33,36]. Although opioid-sparing strategies are well studied [6,37,38,39,40], reports of complete opioid-free THA remain limited [40,41]. Case reports suggest that regional anesthesia combined with multimodal therapy can achieve opioid-free outcomes in select patients, but success depends on careful patient selection, education, interdisciplinary collaboration [40,41], and a comprehensive multimodal approach including complementary techniques. The patient-controlled opioid-free surgical pathway (PCOFSP) addresses this gap by combining personalized multimodal analgesia with structured patient engagement, interdisciplinary collaboration, and flexible complementary interventions, providing a reproducible framework for successful opioid-free surgical outcomes in highly motivated patients who opt for an opioid-free surgical experience. Unlike traditional opioid-sparing protocols, the PCOFSP was designed with the goal of allowing patients to completely avoid opioids throughout their surgical experience. The pathway empowers patients to make informed choices regarding pain management and provides a personalized care plan that integrates regional anesthesia and non-opioid medications with multimodal care and a suite of complementary techniques. These techniques include mindful breathing [21], aromatherapy [26], music therapy [22], auriculotherapy [23], hypnosis [24], acupuncture [25], nanotechnology patches [27], and digital cognitive-behavioral tools such as RxWell to preoperatively target both the physiological and psychological dimensions of pain [33,36]. This paper presents the case study of a 67-year-old male patient who underwent two successful opioid-free THAs within 5 months. This case not only underscores the feasibility of opioid-free surgical care but also demonstrates how positive patient experiences can influence clinical practices and drive broader institutional change.

A 67-year-old male patient (weight: 80.3 kg; height: 167.6 cm) with no known drug allergies was scheduled for elective right THA. His medical history included hypertension, benign prostatic hyperplasia status post-transurethral resection of the prostate, and bilateral hip osteoarthritis. He reported no known drug allergies and expressed a strong desire to avoid opioid medications during his surgery and recovery.

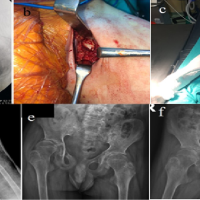

Left hip procedure

During his initial surgical consultation, the patient requested that the orthopedic surgeon avoid prescribing opioids. At that time, the surgeon did not routinely use regional anesthesia, a prerequisite for participation in the PCOFSP. As a result, the patient was not initially screened for opioid avoidance. However, upon the patient explicitly voicing his preferences, the surgeon agreed to consult the acute pain service and supported the use of regional anesthesia. The patient was referred to the PCOFSP and received structured education from the nurse practitioner (NP) about available non-opioid strategies. He consented to the program and selected mindful breathing, ice therapy, and aromatherapy using the Lavender-Peppermint Elequil® Aromatab (Beekley Corporation, Bristol, CT). On the day of surgery, an electronic power plan reflecting the patient’s preference for opioid avoidance and selected complementary techniques was implemented. An “opioid-free” wristband and chart sticker were applied to indicate opioid refusal. Next, the patient received oral acetaminophen 1000 mg, celecoxib 400 mg, and gabapentin 600 mg after peripheral intravenous access was established, and vital signs were continuously monitored. After proper positioning of the patient and under ultrasound guidance (FUJIFILM Sonosite, Bothell, WA), a single-injection lumbar plexus nerve block was performed on his left side with a total dose of 2 mg of intravenous midazolam for sedation, followed by an additional 2 mg at the time of the patient’s transfer to the operating room. A total of 30 mL of 0.375% bupivacaine was administered incrementally at the level of the lumbar plexus under direct visualization. Intraoperatively, spinal anesthesia was performed using a 24-gauge pencil-point needle (B. Braun, Bethlehem, PA) with intrathecal administration of 1.6 mL of 0.75% bupivacaine. The patient received lidocaine 60 mg, cefazolin 2 g, dexamethasone 4 mg, ketamine 20 mg, phenylephrine 80 mcg in divided doses, norepinephrine 38.4 mcg in divided doses, ephedrine sulfate 30 mg in divided doses, magnesium sulfate 2 g, tranexamic acid 2000 mg, ondansetron 4 mg, and propofol 513.42 mg. Postoperatively, the patient received intravenous acetaminophen 1000 mg and oral ibuprofen 800 mg in the recovery room, where a pain score of 1/10 was recorded. Upon transferring to the inpatient unit, his pain increased to a score of 2. By post-operative day (POD) 1, the patient reported a pain score of 0; his pain was managed through scheduled multimodal analgesia and the use of non-pharmacologic interventions: Mindful breathing, ice therapy, and aromatherapy using the Lavender-Peppermint Elequil® Aromatab (Beekley Corporation, Bristol, CT). The patient’s discharge regimen included oral acetaminophen 500 mg (two tablets every 8 h for 15 days), aspirin 81 mg twice daily for 35 days, cefadroxil 500 mg every 12 h for 7 days, docusate 100 mg twice daily for 10 days, ibuprofen 800 mg every 8 h for 10 days, and ondansetron 4 mg every 8 h as needed.

Right hip procedure

Five months after the initial left THA, the patient underwent the contralateral THA using the same regional anesthesia approach. Although the operating surgeon had not initially planned a regional nerve block, the patient requested opioid-free surgery on the day of the procedure. In response, the orthopedic surgeon contacted the acute pain team, and an NP connected directly with the patient to develop a revised patient-controlled plan. For his right THA, the patient chose mindful breathing, aromatherapy, and the addition of a nanotechnology NeuroCuple™ patch (nCap Medical LLC, Heber City, UT), along with lidocaine patches. While the anesthetic technique and pre-operative medications remained consistent with those from the first surgery, the right THA incorporated enhanced complementary techniques aligned with the patient’s evolving preferences. On the day of surgery, the same complementary techniques used for the left THA, mindful breathing, and aromatherapy, were implemented. However, at the patient’s request, the aromatherapy was changed from Lavender-Peppermint Elequil® Aromatabs to Lavender-Sandalwood Elequil® Aromatab (Beekley Corporation, Bristol, CT). Intraoperative medications included lidocaine 60 mg, cefazolin 2 g, dexamethasone 4 mg, ketamine 20 mg, ephedrine sulfate 20 mg, magnesium sulfate 2 g, phenylephrine 720 mcg in divided doses, ondansetron 4 mg, tranexamic acid 2000 mg, and propofol 343.235 mg. In the post-anesthesia care unit, one NeuroCuple™ patch was applied at the incision site, and the patient was educated on its use. He also received intravenous acetaminophen 1000 mg. A transdermal lidocaine patch was applied for 12-h on/off cycles. Pain scores remained at 0 during initial recovery but increased to 4 upon transfer to the inpatient unit, and to 7 by POD 1. Pain was managed with a scheduled regimen of oral acetaminophen 1000 mg every 6 h, celecoxib 200 mg twice daily, and continued use of the NeuroCuple™ and lidocaine patches. Discharge prescriptions were similar to those from the first surgery; however, the patient demonstrated greater consistency with non-opioid interventions and increased engagement with complementary modalities, particularly the NeuroCuple™ patch, which he requested to continue using at home during physical therapy. He noted that his pain was more intense during rehabilitation after the left hip surgery 5 months prior.

The PCOFSP was developed to offer an opportunity for patients to avoid opioids with the goal of undergoing opioid-free surgery. The core of this program is based on the use of regional anesthesia and a multimodal approach to pain management [12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19]. Although regional anesthesia and multimodal care are often used to minimize opioids, evidence shows that regional anesthesia achieves opioid-free anesthesia in only 46.7% and 12% of cases, respectively. The predictive value of these approaches for a given patient remains to be established [8,20]. Therefore, the reported success rate of these techniques is not enough to reliably satisfy a patient’s request for opioid-free surgery. The PCOFSP expands on traditional approaches by incorporating validated complementary techniques, enhancing interdisciplinary communication, and ensuring proper patient identification and follow-up. This comprehensive strategy addresses both physical and psychological factors influencing surgical pain. Evidence supports the concept that mood disorders can increase post-operative pain and opioid requirement [31,32] The patient chose aromatherapy and mindful breathing during both surgeries, utilizing techniques specifically aimed at managing the psychological component of pain. For his first surgery (left THA), he expanded his non-pharmacologic regimen to include transdermal lidocaine patches and NeuroCuple™ patches, which utilize nanotechnology [27]. His request to modify the aromatherapy scent postoperatively illustrates the model’s flexibility in addressing both the physical and emotional aspects of pain. For his second surgery (right THA), he again incorporated transdermal lidocaine and NeuroCuple™ patches into his regimen. In addition, he requested a change in aromatherapy scent from Lavender Sandalwood Elequil® Aromatabs to Lavender Peppermint Elequil® Aromatabs. Evidence suggests that combining complementary modalities can produce synergistic effects, addressing pain and anxiety through multiple mechanisms and ultimately improving patient outcomes [28]. One notable aspect of this case is the importance of a team approach [42]. The patient was initially not identified for the PCOFSP due to the surgeon’s reluctance to use regional anesthesia, which is a program requirement. However, after the patient firmly requested an opioid-free experience and the surgeon agreed to proceed with a lumbar plexus block and spinal anesthesia, he was referred to our team and enrolled in the pathway. After this surgeon/patient interaction, the surgeon requested that all his patients be systematically approached before surgery by the NP, with the understanding that the same approach would be used if the patient requested an opioid-free surgery. This prompted a collaborative discussion among the care team and led to a revised anesthetic plan. This highlights the potential for the PCOFSP to not only benefit individual patients but also influence broader institutional practices, encouraging more widespread adoption of opioid-sparing strategies. The patient’s decision to pursue the same opioid-free approach for his right THA highlights the significance of shared decision-making and positive reinforcement from previous successful experience [34]. This highlights the fact that a well-supported initial encounter with the opioid-free model can foster repeat participation, with patient satisfaction being a key recruitment tool. Recruitment into the PCOFSP relies heavily on informed patient engagement and interdisciplinary collaboration. The NP plays a central role by providing structured pre-operative counseling and education, explaining pharmacologic and non-pharmacologic options, and reinforcing strategies to manage pain and anxiety. This shared decision-making process empowers patients to maintain confidence in their ability to recover without opioids and ensures that they are well prepared for post-operative expectations. Importantly, the PCOFSP does not exclude patients based on medical complexity but instead evaluates their physiological readiness and psychological preparedness. A crucial element is assessing not only the patient’s physiological suitability, but also their belief in their ability to succeed without opioids. Existing literature on opioid-free post-operative pain management shows mixed results, with most studies reporting no significant differences in outcomes, though some highlight better pain relief with non-opioid intervention [7]. Furthermore, very few studies to date have examined combining non-pharmacologic adjuncts with multimodal analgesia, which may be key in optimizing outcomes for opioid-free recovery [22,27,29,30,35]. While existing studies on opioid-sparing approaches for THA typically focus on opioid avoidance during the intraoperative phase, few have demonstrated complete opioid avoidance throughout the entire post-operative period [6,37,38,39]. In addition, only one case study has examined how combining different regional blocks can optimize analgesic coverage and eliminate the need for opioids postoperatively [40]. Limitations of this case study include the fact that it is based on a single patient. As with any case report, studies involving larger numbers of patients are required to better assess the proposed PCOFSP. Another limitation is the lack of a control group; in this context, a control would be defined as a patient refusing opioids and undergoing surgery. Such patients may decline opioids when conscious but are still at risk of receiving them during anesthesia or recovery because of communication gaps or the absence of a systematic approach for managing surgical patients who refuse opioids. Our experience with this challenge led to the development of the PCOFSP program. In this case, outcomes were assessed only during the immediate perioperative and early recovery periods, without long-term data on pain recurrence, functional recovery, or complications. The patient’s high motivation and explicit refusal of opioids introduces selection bias, and the variability in complementary modalities used limits attribution of outcomes to specific interventions. Standardized functional assessments, such as WOMAC, HOOS, or SF-36, were not applied, and implementation depended on surgeon and institutional willingness, which may restrict broader applicability. Economic analyses of multimodal and complementary techniques were not included, and potential publication bias must be acknowledged. Nevertheless, this case demonstrates the feasibility of a PCOFSP, highlighting the value of structured multidisciplinary care, patient engagement, and individualized multimodal strategies. Future studies incorporating larger cohorts, control groups, standardized outcome measures, longitudinal follow-up, and cost-effectiveness analyses are needed to validate the effectiveness and generalizability of the PCOFSP across diverse surgical populations and settings. As the first known report of a successful patient-controlled, opioid-free pathway for bilateral hip arthroplasties, this case is highly relevant to orthopedic surgery and perioperative care. Its implications, however, extend across multiple surgical specialties. Since the PCOFSP’s launch in May 2024, early outcomes have demonstrated both efficacy and scalability. As of this report, 74% of all ambulatory participants (133 of 179) have completed their surgeries without opioids. Specifically, 82.5% (33 of 40) of patients undergoing THA avoided opioids.

This case highlights the importance of a personalized, multidisciplinary approach integrating regional anesthesia, non-opioid pharmacologic therapy, and complementary techniques, education, and teamwork to satisfy a patient’s request to undergo an opioid-free surgery for THA. Beyond avoiding opioids, this case also shows how a patient-centered, controlled program based on a multidisciplinary approach that addresses both the physical and psychological aspects of surgical pain provides a replicable framework that extends across surgical specialties and contributes to broader institutional change, offering valuable insights for advancing pain management and promoting adoption of patient-driven, opioid-free perioperative care models.

This case illustrates the feasibility and effectiveness of a PCOFSP in total hip arthroplasty, demonstrating that individualized, multidisciplinary pain management by combining regional anesthesia, non-opioid medications, and complementary techniques can support successful opioid-free recovery. The PCOFSP is a promising model for other specialties seeking to reduce opioid exposure while maintaining effective pain control, reinforcing that patient engagement is not only beneficial but also essential. Importantly, it highlights how patient advocacy and interdisciplinary collaboration can influence provider practice and institutional culture, offering a model for opioid-free surgical care across specialties.

References

- 1. Neuprez A, Neuprez AH, Kaux JF, Kurth W, Daniel C, Thirion T, et al. Total joint replacement improves pain, functional quality of life, and health utilities in patients with late-stage knee and hip osteoarthritis for up to 5 years. Clin Rheumatol 2020;39:861-71. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 2. Dawson Z, Stanton S, Roy S, Farjo R, Aslesen HA, Hallstrom BR, et al. Opioid consumption after discharge from total knee and hip arthroplasty: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Arthroplasty 2024;39:2130-6.e7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 3. Stephan BC, Parsa FD. Avoiding opioids and their harmful side effects in the postoperative patient: Exogenous opioids, endogenous endorphins, wellness, mood, and their relation to postoperative pain. Hawaii J Med Public Health 2016;75:63-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 4. Urman RD, Seger DL, Fiskio JM, Neville BA, Harry EM, Weiner SG, et al. The burden of opioid-related adverse drug events on hospitalized previously opioid-free surgical patients. J Patient Saf 2021;17:e76-83. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 5. Fiore JF Jr., El-Kefraoui C, Chay MA, Nguyen-Powanda P, Do U, Olleik G, et al. Opioid versus opioid-free analgesia after surgical discharge: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised trials. Lancet 2022;399:2280-93. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 6. Chassery C, Atthar V, Marty P, Vuillaume C, Casalprim J, Basset B, et al. Opioid-free versus opioid-sparing anaesthesia in ambulatory total hip arthroplasty: A randomised controlled trial. Br J Anaesth 2024;132:352-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 7. Blaber OK, Ioffreda P, Adalbert J, Khan IA, Lonner JH. Opioid-free postoperative pain management in total knee and hip arthroplasty: a scoping review. Journal of Orthopaedic Reports. 2025;4(1):100454. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jorep.2024.100454 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

- 8. Mousad AD, Nithagon P, Grant AR, Yu H, Niu R, Smith EL. Non-opioid analgesia protocols after total hip arthroplasty and total knee arthroplasty: An updated scoping review and meta-analysis. J Arthroplasty 2024;40:1643-52.e6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 9. Olausson A, Svensson CJ, Andréll P, Jildenstål P, Thörn SE, Wolf A. Total opioid‐free general anaesthesia can improve postoperative outcomes after surgery, without evidence of adverse effects on patient safety and pain management: A systematic review and meta‐analysis. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 2022;66:170-85. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 10. Mercado LA, Liu R, Bharadwaj KM, Johnson JJ, Gutierrez R, Das P, et al. Association of intraoperative opioid administration with postoperative pain and opioid use. JAMA Surg 2023;158:854-64. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 11. Feenstra ML, Jansen S, Eshuis WJ, Van Berge Henegouwen MI, Hollmann MW, Hermanides J. Opioid-free anesthesia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Anesth 2023;90:111215. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 12. Matharu GS, Garriga C, Rangan A, Judge A. Does regional anesthesia reduce complications following total hip and knee replacement compared with general anesthesia? An analysis from the national joint registry for England, wales, Northern Ireland and the isle of man. J Arthroplasty 2020;35:1521-8.e5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 13. Mauermann E, Ruppen W, Bandschapp O. Different protocols used today to achieve total opioid-free general anesthesia without locoregional blocks. Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol 2017;31:533-45. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 14. Brandal D, Keller MS, Lee C, Grogan T, Fujimoto Y, Gricourt Y, et al. Impact of enhanced recovery after surgery and opioid-free anesthesia on opioid prescriptions at discharge from the hospital: A historical-prospective study. Anesth Analg 2017;125:1784-92. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 15. Golladay GJ, Balch KR, Dalury DF, Satpathy J, Jiranek WA. Oral multimodal analgesia for total joint arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 2017;32:S69-73. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 16. Passias BJ, Johnson DB, Schuette HB, Secic M, Heilbronner B, Hyland SJ, et al. Preemptive multimodal analgesia and post-operative pain outcomes in total hip and total knee arthroplasty. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2023;143:2401-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 17. Nishio S, Fukunishi S, Fukui T, Fujihara Y, Okahisa S, Takeda Y, et al. Comparison of continuous femoral nerve block with and without combined sciatic nerve block after total hip arthroplasty: A prospective randomized study. Orthop Rev (Pavia) 2017;9:7063. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 18. Macfarlane AJ, Prasad GA, Chan VW, Brull R. Does regional anaesthesia improve outcome after total hip arthroplasty? A systematic review. Br J Anaesth 2009;103:335-45. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 19. Marino J, Russo J, Kenny M, Herenstein R, Livote E, Chelly JE. Continuous lumbar plexus block for postoperative pain control after total hip arthroplasty. A randomized controlled trial. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2009;91:29-37. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 20. Schneider J, Broome B, Keeley D. Narcotic-free perioperative total knee arthroplasty: Does the periarticular injection medication make a difference? J Knee Surg 2021;34:460-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 21. Hanley AW, Gililland J, Garland EL. To be mindful of the breath or pain: Comparing two brief preoperative mindfulness techniques for total joint arthroplasty patients. J Consult Clin Psychol 2021;89:590-600. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 22. Goel SK, Kim V, Kearns J, Sabo D, Zoeller L, Conboy C, et al. Music-based therapy for the treatment of perioperative anxiety and pain-a randomized, prospective clinical trial. J Clin Med 2024;13:6139. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 23. Chelly JE, Orebaugh SL, Rodosky MW, Groff YJ, Monroe AL, Alimi D, et al. Auriculotherapy for prolonged postoperative pain management following rotator cuff surgery: A randomized, placebo-controlled study. Med Acupunct 2025;37:220-30. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 24. Walter N, Leyva MT, Hinterberger T, Rupp M, Loew T, Lambert-Delgado A, et al. Hypnosis as a non-pharmacological intervention for invasive medical procedures – A systematic review and meta-analytic update. J Psychosom Res 2025;192:112117. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 25. Cheng SI, Swamidoss CP, Soffin EM. Perioperative acupuncture: A novel and necessary addition to ERAS pathways for total joint arthroplasty. HSS J 2024;20:122-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 26. Chelly JE, Klatt B, O’Malley M, Groff Y, Kearns J, Khetarpal S, et al. The role of inhalation aromatherapy, lavender and peppermint in the management of perioperative pain and opioid consumption following primary unilateral total hip arthroplasty: A prospective, randomized and placebo-controlled study. J Pain Relief 2023;12(Suppl 1):003. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 27. Chelly JE, Klatt BA, Groff Y, O’Malley M, Lin HH, Sadhasivam S. Role of the neurocuple™ device for the postoperative pain management of patients undergoing unilateral primary total knee and hip arthroplasty: A pilot prospective, randomized, open-label study. J Clin Med 2023;12:7394. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 28. Patsalis PC, Malik-Patsalis AB, Rauscher HG, Schaefers C, Useini D, Strauch JT, et al. Efficacy of auricular acupuncture and lavender oil aromatherapy in reducing preinterventional anxiety in cardiovascular patients: A randomized single-blind placebo-controlled trial. J Integr Complement Med 2022;28:45-50. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 29. Crespin DJ, Griffin KH, Johnson JR, Miller C, Finch MD, Rivard RL, et al. Acupuncture provides short-term pain relief for patients in a total joint replacement program. Pain Med 2015;16:1195-203. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 30. Johnson MI, Paley CA, Jones G, Mulvey MR, Wittkopf PG. Efficacy and safety of transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) for acute and chronic pain in adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis of 381 studies (the meta-TENS study). BMJ Open 2022;12:e051073. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 31. Stone AV, Murphy ML, Jacobs CA, Lattermann C, Hawk GS, Thompson KL, et al. Mood disorders are associated with increased perioperative opioid usage and health care costs in patients undergoing knee cartilage restoration procedure. Cartilage 2022;13:19476035221087703. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 32. Ghoshal A, Bhanvadia S, Singh S, Yaeger L, Haroutounian S. Factors associated with persistent postsurgical pain after total knee or hip joint replacement: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Pain Rep 2023;8:e1052. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 33. Gorsky K, Black ND, Niazi A, Saripella A, Englesakis M, Leroux T, et al. Psychological interventions to reduce postoperative pain and opioid consumption: A narrative review of literature. Reg Anesth Pain Med 2021;46:893-903. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 34. Kuosmanen L, Hupli M, Ahtiluoto S, Haavisto E. Patient participation in shared decision‐making in palliative care – an integrative review. J Clin Nurs 2021;30:3415-28. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 35. Bello CM, Mackert S, Harnik MA, Filipovic MG, Urman RD, Luedi MM. Shared decision-making in acute pain services. Curr Pain Headache Rep 2023;27:193-202. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 36. Kaynar AM, Lin C, Sanchez AG, Lavage DR, Monroe A, Zharichenko N, et al. SuRxgWell: Study protocol for a randomized controlled trial of telemedicine-based digital cognitive behavioral intervention for high anxiety and depression among patients undergoing elective hip and knee arthroplasty surgery. Trials 2023;24:715. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 37. Kukreja P, Schuster B, Northern T, Sipe S, Naranje S, Kalagara H. Pericapsular nerve group (PENG) block in combination with the quadratus lumborum block analgesia for revision total hip arthroplasty: A retrospective case series. Cureus 2020;12:e12233. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 38. Zhang XY, Ma JB. The efficacy of fascia iliaca compartment block for pain control after total hip arthroplasty: A meta-analysis. J Orthop Surg Res 2019;14:33. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 39. Bullock WM, Yalamuri SM, Gregory SH, Auyong DB, Grant SA. Ultrasound‐guided suprainguinal fascia iliaca technique provides benefit as an analgesic adjunct for patients undergoing total hip arthroplasty. J Ultrasound Med 2017;36:433-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 40. Owen RL, Kerfeld MJ, Panchamia JK, Olsen DA, Amundson AW. Opioid‐free perioperative analgesia for revision total hip arthroplasty in a patient with a history of substance use disorder. Case Rep Anesthesiol 2025;2025:5521332. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 41. Margonari HA, Goel SK, Chelly JE. Case report: Use of a patient-driven, opioid-free surgical pathway for left total knee arthroplasty in a patient refusing opioids. A A Pract 2025;19:e01974. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 42. Davis MJ, Luu BC, Raj S, Abu-Ghname A, Buchanan EP. Multidisciplinary care in surgery: Are team-based interventions cost-effective? Surgeon 2021;19:49-60. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]