Corrective ulnar osteotomy with annular ligament reconstruction offers reliable functional recovery and stable reduction in neglected pediatric Monteggia fractures.

Dr. Ajay Sharma, Department of Orthopaedics, Dr. BSA Medical College and Hospital, Rohini, New Delhi, India. E-mail: doc.ajaysharma@aol.com

Introduction: Neglected Monteggia fracture-dislocations in children remain challenging due to adaptive deformities of the ulna, chronic radial head dislocation, and soft tissue contractures. While early recognition ensures excellent outcomes, delayed cases often require complex reconstructive surgery. This study presents the clinical and radiological outcomes of a case series involving corrective oblique ulnar osteotomy in neglected Monteggia fractures (NMF), open reduction of the radial head, temporary transcapitellar fixation, and annular ligament reconstruction (ALR).

Materials and Methods: Eight children (5 males and 3 females; mean age 9.9 years) with NMF presenting >4 weeks after trauma were retrospectively reviewed over a 3-year period. The mean delay from injury to surgery was 11.6 months. All underwent oblique flexion osteotomy of the ulna with plate fixation, open reduction of the radial head, temporary Kirschner wire stabilization, and ALR using an extensor carpi radialis fascial sling. Clinical outcomes were assessed by range of motion and the Mayo Elbow Performance Index (MEPI), while radiological outcomes were graded as good, fair, or poor. Mean follow-up was 30.1 months.

Results: At final follow-up, mean flexion improved from 110.6° to 133.1° and mean extension from 9.4° to 3.1°. Forearm supination and pronation averaged 81.9° and 66.3°, respectively. The mean MEPI score increased from 77.6 preoperatively to 91.3 postoperatively, indicating significant functional improvement. Stable reduction of the radial head was maintained in six patients, while one showed subluxation and one developed arthritic changes. Complications included heterotopic ossification in one case and delayed union requiring revision in another.

Conclusion: Corrective ulnar osteotomy combined with open reduction, temporary fixation, and ALR provides reliable functional recovery and stable reduction in neglected pediatric Monteggia fractures. Despite delayed presentation, favorable outcomes can be achieved with this comprehensive surgical approach.

Keywords: Neglected Monteggia, extensor carpi radialis, Mayo elbow performance index, ulnar osteotomy, radial head.

Monteggia fracture is a fracture shaft of ulna (proximal 1/3rd) with radial head dislocation, first described by Monteggia et al., in 1814 [1,3]. Incidence of Monteggia fractures is <2% of forearm injuries in children and adults [1-3]. Neglected Monteggia fractures (NMFs) are fractures of the proximal ulna with the dislocation of the radial head, untreated or misdiagnosed, even after 4 weeks of the injury [4]. Typical pathological changes of NMF include malunion and angulation of the ulna, refractory dislocation of the radial head, and soft tissue injury [1,2]. Due to radial head dislocation, the capitellar facet becomes atrophic and flattened, and the radial head loses its crateriform facet due to its growth without the limitation of the humeral facet. Dislocated proximal radio-ulnar joint also results in the degeneration of the radial notch, which could block the reduction of the radial head [2]. As a result, the unmatched humeroradial joint becomes painful and may eventually develop osteoarthritis [1,2,3]. Annular ligament ensures the stability of the radiocapitellar joint by surrounding the radial head. This ligament may get torn or entrapped by the dislocation of the radial head due to an acute Monteggia fracture [5,6]. Unlike an acute fracture, the main symptoms of NMF are usually an antebrachial osseous protuberance and a prolonged history of trauma, rather than pain in the elbow joint, as the fracture has already healed [1,2,3]. On examination, an abnormal osseous protuberance is usually seen or felt in the forearm. Along with various degrees of cubitus valgus, the rotation of the forearm and the flexion of elbow are often limited due to instability of the radial capitellar joint [1,3,4]. Other manifestations may include peripheral nerve involvement (sensory or motor impairment caused by a tardy ulnar nerve palsy or a posterior interosseous nerve palsy) [7,8]. The radiological diagnosis of NMF focuses on recognizing the angulation deformity of the ulna, the dislocation of the radial head, and the rupture of the annular ligament. The ulna fracture in NMF is healed with shortening and angulation. Early surgical intervention is recommended to lessen complications. However, the surgical outcome after open reduction depends on patient age at the time of open reduction and the interval between Monteggia fracture and surgery and remains controversial. With respect to age, Horii et al. [9] reported that open reduction was beneficial for patients younger than 12 years of age without radial head deformity, and this finding was confirmed by Wang and Chang [10]. With regard to the interval between the injury and open reduction, the findings have varied among reports, with Wang and Chang [10] stating that the acceptable interval is 3 years, and Stoll et al. [8] state that it is 4 years. The main aim of surgical intervention is correction of ulna angular deformity, stable reduction of radial head, and restoring alignment of the radiocapitellar joint [1, 2,8-16]. Various studies reported variety of treatments, varying from position to perform ulnar osteotomy, options for fixation, open or closed reduction of radial head, transcapitellar k-wire fixation of radiocapitellar joint and the reconstruction of the annular ligament, or some amalgamation of these techniques, there still remains no standard protocol or guidelines [8,9,10,11,12,13,16]. Ulna osteotomy should be done to correct bony malunion as angular deformity blocks the radial head from reduction [13]. Ulnar osteotomy and gaining length create intrinsic tension in the interosseous membrane to maintain reduction of the radial head [1,2,12]. Park et al. [13] noted location of ulnar angular deformity and its magnitude likely determines whether osteotomy should be performed. Radial head reduction alone could be performed in patients whose maximum ulnar deformity is <4 mm or ulnar deformity lies in distal 40% of ulna shaft [14]. Proximal ulna osteotomy should allow at least 2 screws in the proximal ulna. Di Gennaro et al. [11] reported that proximal 1/3rd ulnar osteotomy presents a significantly lower rate of non-union than osteotomy of the middle and distal ulna. Fixation of ulnar osteotomy can be done internally (k-wires or locking compression plate) or externally. Immediate correction of the bending of ulna requires 10–15° of dorsal or ulnar angulation for simultaneous radial head reduction [2]. Locking compression plate provides adequate stability and another benefit is that it could be shaped to adapt to the position of ulna. Most studies have performed open reduction of the radial head [11]. It remains still controversial whether transcapitellar pinning should be performed after radial head reduction while some studies suggest transcapitellar pinning at 90° elbow flexion to provide stability and soft tissue reconstruction [15]. Various surgical techniques for annular ligament reconstruction (ALR) have been described over the years like using a triceps brachii tendon strip (bell tawse), palmaris longus tendon, extensor carpi radialis longus [2,8]. Recently, techniques using brachioradialis, palmaris longus tendon, and the superficial head of the brachialis muscle have been proposed [1,2,3,16]. On the other hand, annular ligament remnant in chronic Monteggia fracture cases may develop heterogenic tissue of which the reconstruction would result in stenosis of the radial neck, delayed growth of the radius, and limited elbow joint movement [16]. In addition, the outcome of the surgical treatment of chronic radial head dislocation is uncertain, with reports of subluxation and re-dislocation, as well as complications including elbow stiffness, instability, non-union of the osteotomies, avascular necrosis of the radial head, neurovascular injury (posterior interosseous nerve), and infection [2,7]. Secondary degenerative arthritis may also occur. Few reports have described the details related to these operative techniques, but no long-term investigations of clinical or radiographic results in a large number of patients have been published, to our knowledge. We review the clinical and radiological outcome of 8 patients who were treated with a specific technique of ulnar osteotomy with angulation and lengthening and internal fixation with locking compression plate, open reduction of the radial head, and temporary fixation of the radial head with a transcapitellar k-wire for radiocapitellar joint and ALR using extensor carpi radialis longus sling and immobilization which is rare and less described procedure.

This retrospective review included eight patients presenting with NMF at the orthopedic outpatient department of our institution, characterized by proximal ulnar fractures with persistent radial head dislocation for more than 4 weeks after the initial trauma. Inclusion criteria consisted of delayed surgery beyond 4 weeks, radiological evidence of unreduced radial head dislocation, and clinical findings such as pain, deformity, or functional restriction requiring operative correction. Patients were excluded if they had acute Monteggia injuries, a history of previous elbow surgeries, ongoing site infections, or pathological fractures. At the time of presentation, time of injury, Bado’s classification, range of motion (ROM) at elbow, and Mayo Elbow Performance Index (MEPI) score were noted. Informed consent for corrective osteotomy was obtained from the guardian of the patient. All corrective procedures were performed by the same orthopedic team under general anesthesia using a standardized surgical approach. Before surgery, each patient underwent a comprehensive clinical assessment to document general health status, mechanism of injury, and any accompanying trauma. Radiological confirmation was achieved through anteroposterior and lateral X-rays of the forearm and elbow. A radial head dislocation was defined if the longitudinal axis of the radial neck did not intersect the central third of the capitellum on the lateral view. When doubt persisted, additional lateral X-rays were obtained in varying positions (supination, pronation, or extension) (Fig. 1). Pre-operative investigations included hematological and biochemical profiles, renal function tests, electrolyte estimation, blood glucose levels (fasting and postprandial), electrocardiography, and chest X-ray.

Figure 1 : Pre-operative radiograph showing Bado’s type 1 neglected Monteggia fracture.

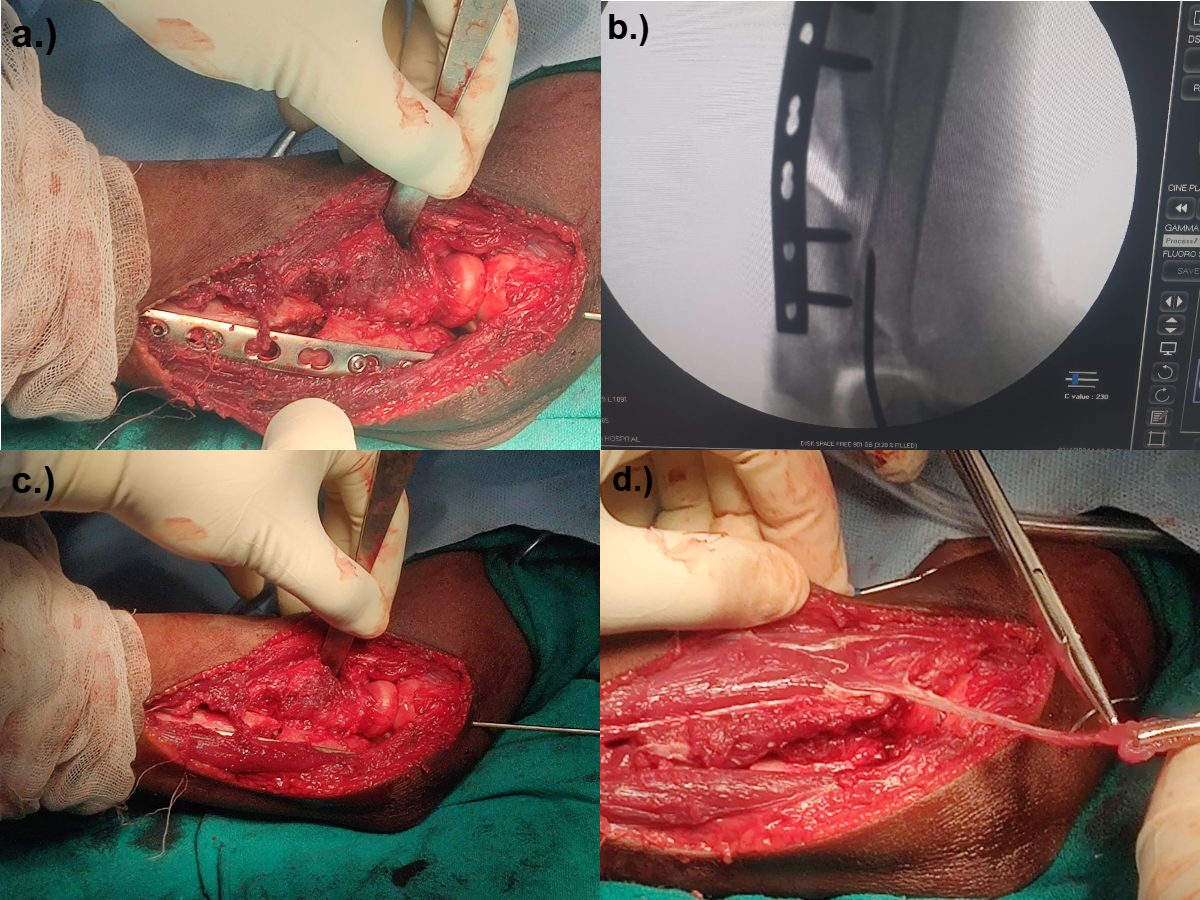

The fracture was approached through the extended Boyd’s approach. First, proximal ulna was exposed. The surgical technique involved an oblique flexion osteotomy of the ulna. The angular cut enabled correction of both length and alignment while maximizing bone-to-bone contact to promote union. If required, lengthening and slight overcorrection were performed to maintain radial head stability. Internal fixation was achieved using contoured plates and cortical screws. The radial head was approached through the same incision. The dislocated radial head was reduced by releasing fibrous adhesions and periarticular contractures, followed by direct visualization and repositioning. To secure reduction, a temporary radio-capitellar Kirschner wire was inserted with care to prevent articular surface injury. ALR was also carried out using a fascial sleeve from the extensor carpi radialis longus sheath, which was looped around the radial head to mimic ligamentous stabilization and re-enforced with 3-0 proline. In five individuals, the K-wire was removed intraoperatively, whereas in three, it was retained and removed 6 weeks later. Wound was closed in layers over 12- size Romo Vac drain. Sterile dressing and above-elbow slab were given (Fig. 2).

Figure 2: (a and b) Fixation of osteotomy of proximal ulna with LCP, (c and d) radial head reduced and temporary fixation with k-wire (C-arm and intra-operative image), Fascial sheath taken from extensor carpi radialis which was tied around head and K-wire was removed.

Postoperatively, the upper limb was immobilized in a cast with the elbow flexed at 90° and the forearm supinated for 4–6 weeks. After confirming stability with follow-up imaging, K-wire removal was performed, followed by a structured rehabilitation program emphasizing progressive mobilization and strengthening (Fig. 3). All patients additionally underwent a supervised institutional shoulder rehabilitation protocol to improve ROM and rotator cuff strength. Monitoring continued for at least 48 weeks, after which plate removal was considered. An additional evaluation was performed 8 weeks following implant removal.

Figure 3: Post-operative radiograph showing radial head reduction.

Radiographic assessments were scheduled at the 6th, 10th, and 16th post-operative weeks, as well as at 8 weeks after plate removal. Functional recovery was assessed using the MEPI at the same intervals. Radiographic outcomes were graded as good (complete reduction of the radial head and no arthritic changes), fair (reduction with subluxation or degenerative changes), and poor (persistent dislocation).

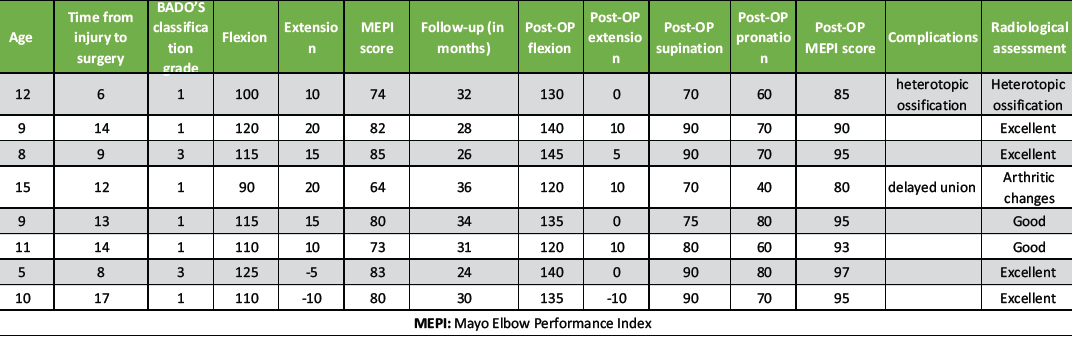

We operated 8 patients (5 males and 3 females) of neglected Monteggia fracture dislocation within a period of 3 years from July 2023 to July 2025 (Table 1).

Table 1: Master chart of all the cases of neglected Monteggia fracture

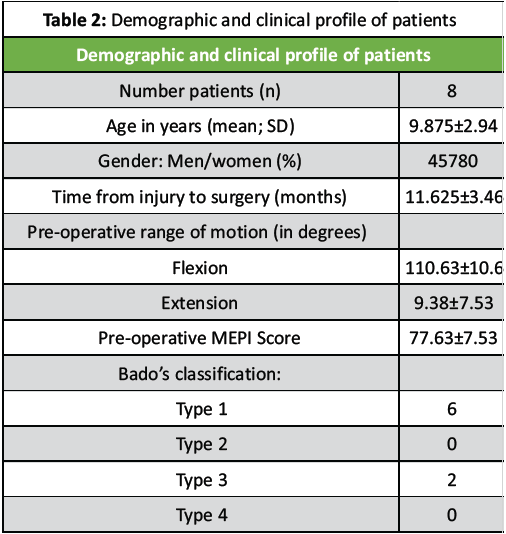

All patients had a history suggestive of trauma. The mean age of the patients was 9.875 ± 2.94 years. The fracture was considered as being neglected when the time of presentation was more than 4 weeks from injury. The mean interval from injury to surgery was 11.625 ± 3.46 (range = 6–17). The injuries of all patients were classified according to Bado’s classification: 6 were classified as Bado’s type 1 and 2 were classified as Bado’s type 3. Pre-operatively, the mean flexion and the mean extension were 110.625 ± 10.6 (range = 90–125) and 9.375 ± 7.53 (range=−10–20). The MEPI score pre-operatively was 77.625 ± 6.46 (Table 2).

Table 2: Demographic and clinical profile of patients

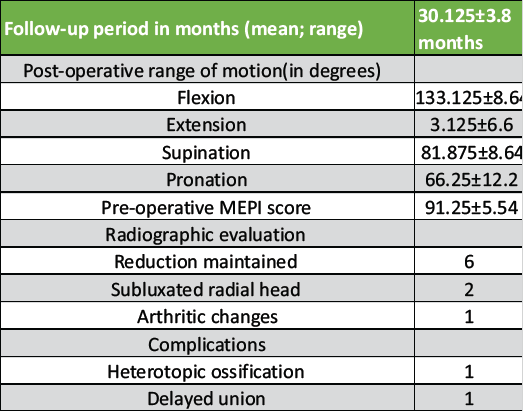

Patients were followed up till 1months post-implant removal. The mean follow-up time was 30.125 ± 3.8 months. Post-operatively, the flexion, extension, supination, and pronation were recorded at 16th week post-operatively and at the final follow-up. The mean post-operative flexion, extension, supination, and pronation were 133.125 ± 8.64, 3.125 ± 6.6, 81.875 ± 8.64, and 66.25 ± 12.2, respectively. The post-operative MEPI score at final follow-up was 91.25 ± 5.54 (Table 3).

Table 3: Post-operative clinical and radiological evaluation at final follow-up

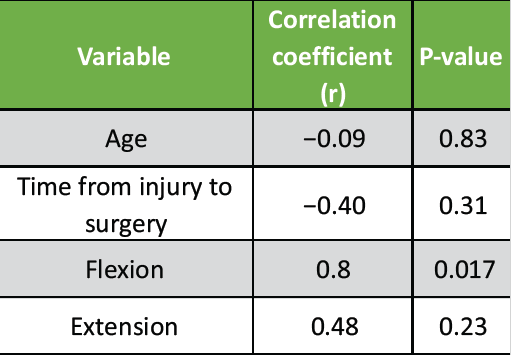

Flexion is the only factor with statistically significant positive correlation with MEPI (P < 0.05) meaning greater elbow flexion is strongly associated with better functional outcome. Extension shows a moderate, but non-significant, positive relationship. Time to surgery tends to reduce MEPI scores but this is not statistically significant. In our dataset, age and time from injury to surgery show a positive correlation with MEPI score (Table 4).

Table 4: Pearson correlation coefficients (r) and P-values to test strength and significance

At the time of our latest follow-up, the radial head was maintained in its position in 6 of our patients. Radiographs at the last follow-up revealed subluxation of radial head in 1 patient. There were arthritic changes in 1 of our patients (Table 3). We encountered complications of heterotopic ossification and delayed union in 2 of our patients. The patient with delayed union was managed by re-freshening the bony edges at the osteotomy non-union site and re-plating with bone grafting.

Neglected Monteggia fracture-dislocations remain a complex and challenging condition in pediatric orthopedics due to adaptive changes in the proximal ulna, chronic dislocation of the radial head, and associated soft tissue contractures. Despite significant advances in diagnosis and treatment strategies, management continues to be debated, particularly with respect to timing of surgery, surgical technique, and long-term outcomes. Our study of eight children with neglected Monteggia lesions contributes to this body of evidence by demonstrating that ALR, combined with corrective osteotomy where needed, can restore near-normal function and yield satisfactory clinical outcomes. The average interval between injury and surgical correction in our cohort was approximately 11.6 months. Delay in treatment has been consistently associated with increased technical difficulty and poorer outcomes. Ramski et al. [17], Wintges K [18], and Lädermann A [19] emphasized that early recognition and management of Monteggia fractures in children generally lead to excellent results, whereas missed or neglected injuries often require more extensive surgery. Similarly, Zivanovic et al. [20], Yi [21], Zhang [22], Eamsobhana [23], and Tan [24] demonstrated that longer delays before intervention correlated with reduced ROM and higher complication rates. Nakamura et al. [25], in a long-term follow-up of surgically treated neglected cases, also reported that late presentations had higher rates of residual deformity and restricted forearm rotation. In this context, our results, showing a mean post-operative flexion–extension arc of 130° and forearm rotation with supination of 82° and pronation of 66°, are encouraging despite the relatively long delays, highlighting that meaningful recovery is possible even in delayed cases when anatomical reduction and annular. Multiple surgical strategies have been described for neglected Monteggia lesions, including open reduction of the radial head alone, corrective ulnar osteotomy, ALR, or combinations thereof. Eamsobhana et al. [23] reported that open reduction of the radial head without addressing the ulna often resulted in recurrence of dislocation, stressing the importance of restoring ulnar alignment. Tan et al. [24] and Goyal T et al [26], in a systematic review and meta-analysis, concluded that the combination of ulnar osteotomy and ALR produced the most reliable results. Our series aligns with these findings, as all patients underwent ALR and corrective osteotomy when required, leading to stable reductions and improved motion. The role of ALR remains debated. Some authors caution that over-tightening or inappropriate reconstruction may limit motion [22,24], while others highlight its necessity for stability [27,28]. In our cohort, consistent reconstruction of the annular ligament produced favorable outcomes without significant stiffness, supporting the view that it is a key component of surgical management in neglected cases. Post-operative functional outcomes in our series were favorable. The mean Mayo elbow performance score improved from 77.6 preoperatively to 91.25 postoperatively, reflecting the transition from a “fair–good” to a “good–excellent” category. This degree of functional improvement is consistent with results from prior series. Nakamura et al. [25] observed long-term functional gains after open reduction and osteotomy, although mild limitations in pronation persisted in some cases. Wintges et al. [18] proposed a treatment algorithm that emphasized individualized surgical planning, reporting satisfactory function in the majority of cases when stability and alignment were restored. Lädermann et al. [19] similarly documented that corrective osteotomy and soft tissue balancing yielded reliable improvement in elbow function, with residual deficits in forearm rotation being the most common limitation. Compared with these reports, our patients achieved comparable or slightly superior forearm motion, with supination (82°) nearing normal values and pronation (66°) falling within the functional range required for daily activities. This suggests that reconstructing the annular ligament in all cases may have contributed to the stability necessary for functional recovery. Complications following surgery for NMF are common and include loss of reduction, redislocation of the radial head, stiffness, and neurovascular compromise. Yi et al. [21] emphasized the importance of addressing both osseous and soft tissue deformities to minimize such risks. In our cohort, complications were limited, and none of the patients experienced redislocation during follow-up. The preservation of satisfactory motion arcs suggests that our reconstruction techniques were effective in balancing stability with mobility.

Study limitations and future directions

While our results are promising, several limitations must be acknowledged. The sample size of eight patients is modest, which restricts the generalizability of our findings. In addition, the mean follow-up of 30 months, although sufficient to document early functional outcomes, may not fully capture late complications such as degenerative changes of the radial head or elbow joint. Previous long-term studies, such as those by Nakamura et al. [25], have demonstrated that even with good early outcomes, degenerative changes may develop over time. Larger, multicenter studies with extended follow-up would be valuable in further defining the role of ALR and in refining prognostic indicators.

Our series adds to the growing evidence that neglected Monteggia fracture–dislocations, even when treated after significant delay, can achieve good functional outcomes with appropriate surgical strategies. The consistent use of ALR in our patients yielded stable reductions and significant improvements in motion and MEPS scores. When compared with published data, our outcomes are in line with or superior to prior reports, particularly with respect to forearm rotation. While early recognition and treatment remain the ideal, reconstructive surgery remains a viable option for restoring function in children with neglected lesions.

Even in delayed presentations, neglected Monteggia fracture–dislocations in children can be effectively managed with corrective ulnar osteotomy, open reduction, temporary fixation, and annular ligament reconstruction. This comprehensive approach restores stability and function, highlighting the importance of early recognition but offering a reliable surgical solution when diagnosis is delayed.

References

- 1. Soni JF, Valenza WR, Pavelec AC. Chronic monteggia. Curr Opin Pediatr 2019;31:54-60. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 2. Hubbard J, Chauhan A, Fitzgerald R, Abrams R, Mubarak S, Sangimino M. Missed pediatric Monteggia fractures. JBJS Rev 2018;6:e2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 3. Delpont M, Louahem D, Cottalorda J. Monteggia injuries. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res 2018;104:S113-20. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 4. Chin K, Kozin SH, Herman M, Horn BD, Eberson CP, Bae DS, et al. Pediatric monteggia fracture-dislocations: Avoiding problems and managing complications. Instr Course Lect 2016;65:399-407. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 5. Tan J, Mu M, Liao G, Zhao Y, Li J. Biomechanical analysis of the annular ligament in Monteggia fractures using finite element models. J Orthop Surg Res 2015;10:30. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 6. Canton G, Hoxhaj B, Fattori R, Murena L. Annular ligament reconstruction in chronic Monteggia fracture-dislocations in the adult population: Indications and surgical technique. Musculoskeletal Surg 2018;102 Suppl 1:93-102. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 7. Nishimura M, Itsubo T, Horii E, Hayashi M, Uchiyama S, Kato H. Tardy ulnar nerve palsy caused by chronic radial head dislocation after Monteggia fracture: A report of two cases. J Pediatr Orthop B 2016;25:450-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 8. Stoll TM, Willis RB, Paterson DC. Treatment of the missed Monteggia fracture in the child. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1992;74:436-40. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 9. Horii E, Nakamura R, Koh S, Inagaki H, Yajima H, Nakao E. Surgical treatment for chronic radial head dislocation. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2002;84:1183-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 10. Wang MN, Chang WN. Chronic posttraumatic anterior dislocation of the radial head in children: Thirteen cases treated by open reduction, ulnar osteotomy, and annular ligament reconstruction through a Boyd incision. J Orthop Trauma 2006;20:1-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 11. Di Gennaro GL, Martinelli A, Bettuzzi C, Antonioli D, Rotini R. Outcomes after surgical treatment of missed Monteggia fractures in children. Musculoskelet Surg 2015;99 Suppl 1:S75-82. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 12. Najd Mazhar F, Jafari D, Shariatzadeh H, Dehghani Nazhvani H, Taghavi R. Surgical outcome of neglected Monteggia fracture-dislocation in pediatric patients: A case series. J Res Orthop Sci. 2019;6(1):e85225. doi:10.5812/soj.85225.Najd Mazhar F, Jafari D, Shariatzadeh H, Dehghani Nazhvani H, Taghavi R. Surgical outcome of neglected Monteggia fracture-dislocation in pediatric patients: A case series. J Res Orthop Sci 2019;6(1). [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

- 13. Park H, Park KW, Park KB, Kim HW, Eom NK, Lee DH. Impact of open reduction on surgical strategies for missed Monteggia fracture in children. Yonsei Med J 2017;58:829-36. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 14. Shinohara T, Horii E, Koh S, Fujihara Y, Hirata H. Mid- to long-term outcomes after surgical treatment of chronic anterior dislocation of the radial head in children. J Orthop Sci 2016;21:759-65. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 15. Lu X, Wang YK, Zhang J, Zhu Z, Guo Y, Lu M. Management of missed Monteggia fractures with ulnar osteotomy, open reduction, and dual-socket external fixation. J Pediatr Orthop 2013;33:398-402. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 16. Datta T, Chatterjee N, Pal AK, Das SK. Evaluation of outcome of corrective ulnar osteotomy with bone grafting and annular ligament reconstruction in neglected Monteggia fracture dislocation in children. J Clin Diagn Res 2014;8:LC01-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 17. Ramski DE, Hennrikus WP, Bae DS, Baldwin KD, Patel NM, Waters PM, et al. Pediatric monteggia fractures: A multicenter examination of treatment strategy and early clinical and radiographic results. J Pediatr Orthop 2015;35:115-20. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 18. Wintges K, Cramer C, Mader K. Missed Monteggia injuries in children and adolescents: A treatment algorithm. Children (Basel) 2024;11:391. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 19. Lädermann A, Ceroni D, Lefèvre Y, De Rosa V, De Coulon G, Kaelin A. Surgical treatment of missed Monteggia lesions in children. J Child Orthop 2007;1:237-42. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 20. Zivanovic D, Marjanovic Z, Bojovic N, Djordjevic I, Zecevic M, Budic I. Neglected Monteggia fractures in children-a retrospective study. Children (Basel) 2022;9:1100. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 21. Yi Y, Liu C, Xu Z, Xie Y, Cao S, Wen J, et al. What do we need to address when we treat neglected Monteggia fracture in children. Front Pediatr 2024;12:1430549. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 22. Zhang R, Wang X, Xu J, Kang Q, Hamdy RC. Neglected Monteggia fracture: A review. EFORT Open Rev 2022;7:287-94. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 23. Eamsobhana P, Chalayon O, Kaewpornsawan K, Ariyawatkul T. Missed Monteggia fracture dislocations treated by open reduction of the radial head. Bone Joint J 2018;100-B:1117-24. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 24. Tan SH, Low JY, Chen H, Tan JY, Lim AK, Hui JH. Surgical management of missed pediatric monteggia fractures: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Orthop Trauma 2022;36:65-73. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 25. Nakamura K, Hirachi K, Uchiyama S, Takahara M, Minami A, Imaeda T, et al. Long-term clinical and radiographic outcomes after open reduction for missed Monteggia fracture-dislocations in children. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2009;91:1394-404. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 26. Goyal T, Arora SS, Banerjee S, Kandwal P. Neglected Monteggia fracture dislocations in children: A systematic review. J Child Orthop B 2015;9:445-54. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 27. Pari C, Puzzo A, Paderni S, Belluati A. Annular ligament repair using allograft for the treatment of chronic radial head dislocation: A case report. Acta Biomed 2018;90:154-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 28. Maniar A, Kakatkar S. A novel technique of annular ligament reconstruction using extensor carpi radialis longus tendon fascia: A report of 3 cases. Int J Res Orthop 2021;7:679-82. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]