A TenoGlide Tendon Protector Sheet may be used to prevent tendon entrapment of the first extensor compartment after radial column plating for a distal radius fracture.

Dr. David Cinats, Fraser Orthopaedic Institute, 403-233 Nelson’s Cres, New Westminster, British Columbia - V3L 0E4, Canada. E-mail: davidcinats@gmail.com

Introduction: Although volar locking plates are the most commonly used implant method for open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF) of distal radius fractures, complex fractures may require the use of fragment-specific fixation. Radial column plates are placed adjacent to the tendons of the first extensor compartment and may lead to tendon entrapment. This case report demonstrates the use of TenoGlide Tendon Protector Sheet to prevent the formation of tendon adhesions after ORIF of a distal radius fracture.

Case Report: A healthy 35-year-old female suffered a distal radius fracture after a fall from a horse. The patient underwent ORIF with a volar locking and radial column plate, but subsequently developed limited thumb extension postoperatively. Reoperation for hardware removal and tenolysis was performed with a TenoGlide Tendon Protector Sheet placed between the first extensor compartment tendons and adjacent bone. Patient regained full thumb extension by the final follow-up 3 months postoperatively.

Conclusion: Bone-tendon adhesions of the first extensor compartment in the wrist are a possible complication of radial column plating for fixation of distal radius fractures. The TenoGlide Tendon Protector Sheet is effective in preventing first extensor compartment entrapment after radial column plating for distal radius fractures.

Keywords: Distal radius fracture, radial column plate, tendon entrapment.

Fractures of the distal radius are common orthopedic injuries, accounting for 17.5% of all fractures [1,2]. These fractures typically occur after a fall with an outstretched hand but can be seen in more complex polytrauma as well [1]. Although some distal radius fractures can be managed non-operatively, surgical intervention is often required [3,4]. Most distal radius fractures can be stabilized with a volar locking plate; however, more complex fracture patterns may require fragment-specific fixation with radial column, intermediate column, or ulnar column fixation [4,5]. The radial styloid plate, or radial column plate, involves a more lateral approach to visualize the lateral aspect of the radius and radial styloid. This approach requires opening of the tendon sheath of the first and second extensor compartments in the wrist. As a result, the radial styloid plate is implanted near the tendons of the extensor pollicis longus (EPL), extensor pollicis brevis (EPB), and abductor pollicis longus (APL) [6,7]. The proximity of these tendons to the plate increases the risk of post-operative tendon stenosis or entrapment, which may require subsequent intervention to clear adhesions [8]. We present a case of symptomatic first extensor compartment tendon entrapment after ORIF with dual volar locking and radial column plating for a distal radius fracture that was subsequently treated with TenoGlide Tendon Protector Sheet. TenoGlide is a collagen matrix sheath that acts as a barrier between nerves or tendons and surrounding tissue to prevent the formation of adhesions. This report aims to demonstrate the risks around radial column plating and the potential benefits of scar barriers, such as TenoGlide at preventing tendon adhesions around the wrist.

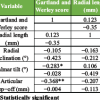

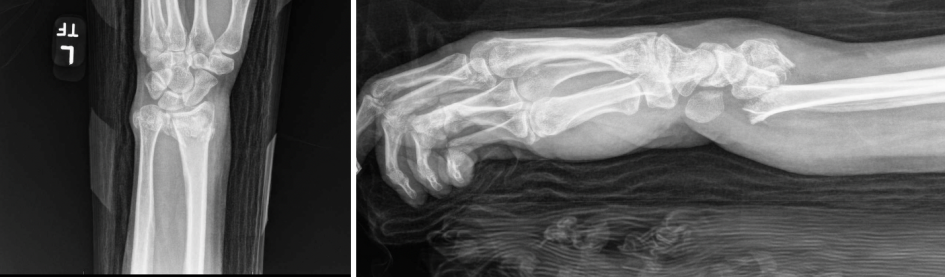

The patient was a healthy 35-year-old schoolteacher who presented with left shoulder, elbow, and wrist fractures after a fall from a horse. The patient had no pertinent past medical history and no prior orthopedic surgeries. Imaging of the left upper extremity revealed a comminuted proximal humerus fracture, terrible triad elbow fracture dislocation, and distal radius fracture with carpal tunnel syndrome (Fig. 1).

Figure 1: Pre-operative lateral (left) and anteroposterior (right) left wrist X-rays.

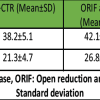

All three injuries were treated during a single procedure. Open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF) was performed on the left shoulder and elbow first, followed by ORIF of the wrist (Fig. 2).

Figure 2: Post-operative lateral left elbow (left) and anteroposterior left shoulder (right) X-rays.

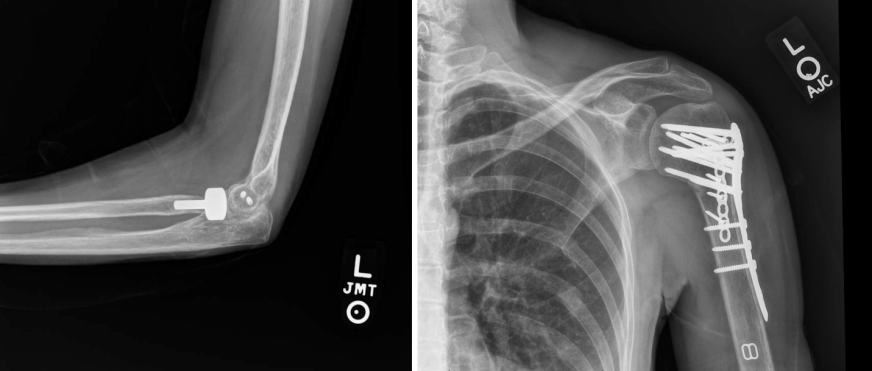

A modified volar Henry approach to the distal radius was utilized in which the incision was made between the radial artery and the flexor carpi radialis tendon. The high-energy nature of the multilevel injury to the left upper extremity resulted in a highly unstable distal radius fracture pattern with a significant amount of metaphyseal radial column comminution. The decision was made to proceed with fragment-specific fixation, and a radial column plate was placed underneath the first extensor compartment in addition to a volar locking plate (Fig. 3).

Figure 3: Post-operative left wrist X-ray. Status post internal fixation with a radial column plate and volar locking plate.

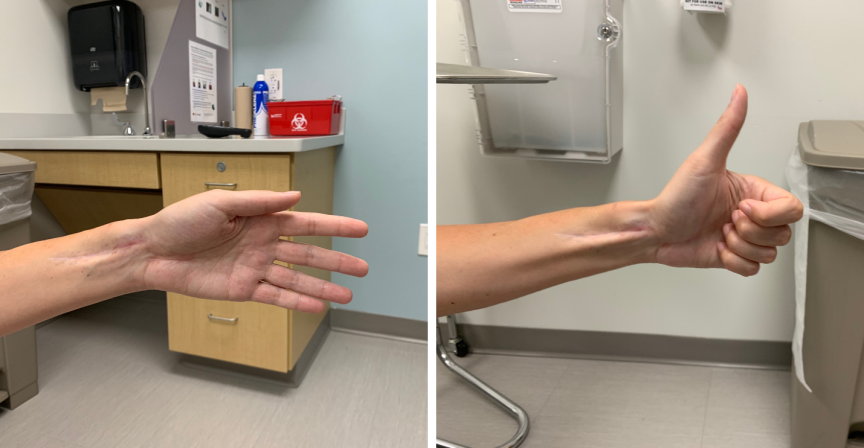

The patient did not experience any perioperative complications and was discharged with a volar wrist splint. At 4 months postoperatively, the patient had recovered a full range of motion (ROM) of the left shoulder, elbow, and fingers, but was limited to 50% of full extension of the left thumb (Fig. 4).

Figure 4: Four-month post-operative thumb extension (left) and thumb extension following subsequent tenolysis and TenoGlide placement (right).

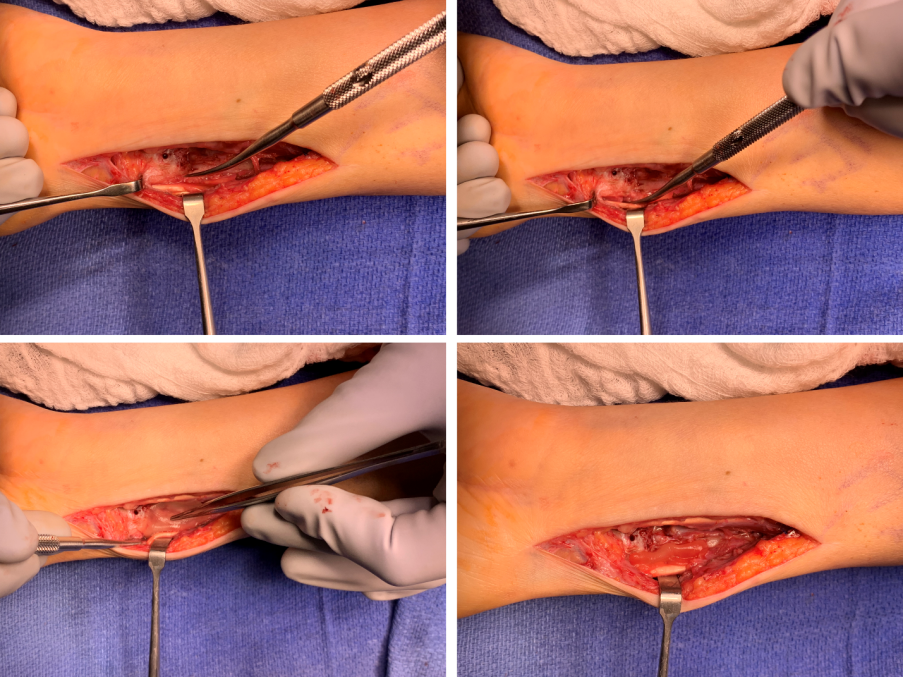

It was suspected that the thumb extension was limited by the radial column plate. The patient elected to proceed with the removal of the radial column plate and tenolysis of the first extensor tendons. The previous incision was used to remove the volar locking plate. The EPB and APL – were observed directly adjacent to the radial column plate and were mobilized to facilitate the removal of the plate. Exploration of the first extensor compartment tendons beyond the footprint of the plate demonstrated adhesions to the surrounding bone and soft tissues. Complete tenolysis of the EPB and APL was then performed. To prevent further scarring of the tendons, a 2.5 cm by 2.5 cm segment of TenoGlide Tendon Protector Sheet was placed between the first extensor compartment tendons and bone (Fig. 5).

Figure 5: Subsequent reoperation with first extensor compartment tenolysis and TenoGlide placement.

TenoGlide is a porous matrix of cross-linked highly purified Type I collagen and glycosaminoglycan that aims to reduce scar tissue formation between tendons and adjacent tissue. The patient was started on an early, active mobilization program. At the 2-week follow-up, the patient already reported substantial improvement in thumb function. Thumb extension was measured at 75% of the predicted. At a final 3-month follow-up, the patient demonstrated continued improvement of thumb ROM with hyperextension of the interphalangeal joint and full extension of the metacarpophalangeal joint.

This report describes a case of EPB and APL entrapment after radial styloid plating for a distal radius fracture that was treated with tenolysis and a TenoGlide Tendon Protector Sheet for subsequent adhesion barrier protection. Peritendinous adhesions are a possible complication after many orthopedic surgeries. Such adhesions are thought to form as a result of inflammatory processes after tissue injury, which can be due to the initial trauma, as well as surgical procedures [9]. Tendon adhesions have been identified as one of the most common complications in the management of distal radius fractures [10,11,12]. The first extensor compartment adhesions observed in this case were likely due to manipulation and retraction of the EPL and APB tendons when fixating with the radial column plate. The TenoGlide Tendon Protector sheet has shown efficacy in animal models [13], but currently, no clinical studies have evaluated its use for preventing tendon adhesions in human subjects. The use of TenoGlide has been documented in prior orthopedic studies with favorable clinical outcomes [14,15,16]. Rioux-Forker and Shin [17] previously presented a case in which TenoGlide was used to create a barrier between EPL tendon and an adjacent bony defect. Our presented case further demonstrates the utility of TenoGlide in barrier protection to prevent bony adhesions. There are alternative scar barriers that have the potential to reduce tendon stenosis, including seprafilm, a hyaluronic acid and carboxymethyl cellulose membrane, and waterborne biodegradable polyurethane films. Finally, research has been directed at barrier protection sheets that are loaded with anti-adhesion pharmacologic agents such as ibuprofen or celecoxib [9]. This study is limited largely by the case report design. It is possible that the prevention of tendon stenosis would have occurred without the use of a scar barrier; however, it is well established that multiple surgical procedures and revision surgery further increases scar tissue formation. In this case, the tendon protector sheet was utilized to prevent potential recalcitrant tendon stenosis during revision surgery in an individual with a known propensity for adhesion formation.

Adhesions of the first extensor compartment in the wrist may develop after distal radius fractures fixed with radial styloid plating. These adhesions can lead to deficits in thumb extension postoperatively and may require subsequent tenolysis to regain full ROM. TenoGlide, a collagen matrix sheet, can be used as a form of barrier protection between the first extensor compartment tendons and adjacent bone to prevent tendon entrapment due to tendon-to-bone adhesions and possibly avoid secondary surgeries to remove implants or perform tenolysis.

The TenoGlide Tendon Protector Sheet can be used to prevent first extensor compartment tendon adhesions after radial column plating for distal radius fractures.

References

- 1. Candela V, Di Lucia P, Carnevali C, Milanese A, Spagnoli A, Villani C, et al. Epidemiology of distal radius fractures: A detailed survey on a large sample of patients in a suburban area. J Orthop Traumatol 2022;23:43. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 2. Court-Brown CM, Caesar B. Epidemiology of adult fractures: A review. Injury 2006;37:691-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 3. Toon DH, Premchand RA, Sim J, Vaikunthan R. Outcomes and financial implications of intra-articular distal radius fractures: A comparative study of open reduction internal fixation (ORIF) with volar locking plates versus nonoperative management. J Orthop Traumatol 2017;18:229-34. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 4. Ochen Y, Peek J, Van der Velde D, Beeres FJ, Van Heijl M, Groenwold RH, et al. Operative vs nonoperative treatment of distal radius fractures in adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Netw Open 2020;3:e203497. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 5. Dabash S, Potter E, Pimentel E, Shunia J, Abdelgawad A, Thabet AM, et al. Radial plate fixation of distal radius fracture. Hand (N Y) 2020;15:103-10. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 6. Tang P, Ding A, Uzumcugil A. Radial column and volar plating (RCVP) for distal radius fractures with a radial styloid component or severe comminution. Tech Hand Up Extrem Surg 2010;14:143-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 7. Hozack BA, Tosti RJ. Fragment-specific fixation in distal radius fractures. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med 2019;12:190-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 8. Seigerman D, Lutsky K, Fletcher D, Katt B, Kwok M, Mazur D, et al. Complications in the management of distal radius fractures: How do we avoid them? Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med 2019;12:204-12. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 9. Akhlaghi S, Ebrahimnia M, Niaki DS, Solhi M, Rabbani S, Haeri A. Recent advances in the preventative strategies for postoperative adhesions using biomaterial-based membranes and micro/nano-drug delivery systems. J Drug Deliv Sci Technol 2023;85:104539. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 10. Oren TW, Wolf JM. Soft-tissue complications associated with distal radius fractures. Oper Tech Orthop 2009;19:100-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 11. Kozin SH, Wood MB. Early soft-tissue complications after fractures of the distal part of the radius. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1993;75:144-53. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 12. Mathews AL, Chung KC. Management of complications of distal radius fractures. Hand Clin 2015;31:205-15. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 13. Turner JB, Corazzini RL, Butler TJ, Garlick DS, Rinker BD. Evaluating adhesion reduction efficacy of type I/III collagen membrane and collagen-GAG resorbable matrix in primary flexor tendon repair in a chicken model. Hand (N Y) 2015;10:482-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 14. Elhassan B. Lower trapezius transfer for shoulder external rotation in patients with paralytic shoulder. J Hand Surg Am 2014;39:556-62. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 15. O’Callaghan PK, Matthews JH, Kirn PT, Angermeier EW, Kokko KP. Bone grafting in total wrist arthrodesis with large bone defects using the reamer-irrigator-aspirator: A case study of 2 patients. J Hand Surg Am 2019;44:620.e1-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 16. Ladak A, Shin AY, Smith J, Spinner RJ. Carpometacarpal boss: An unusual cause of extensor tendon ruptures. Hand (N Y) 2015;10:155-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 17. Rioux-Forker D, Shin AY. Extensor pollicis longus tendon rupture from dorsal nail plate distal radius fixation with concomitant myostatic atrophy. BMJ Case Rep 2020;13:e232659. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]