Interphalangeal joint dislocation of the great toe is a rare injury that is often missed on plain radiographs. A high index of suspicion is therefore required during diagnosis to reduce the chances of overlooking this condition.

Dr. Nischay Kaushik, Department of Orthopaedics, Dr BSA Medical College and Hospital, Rohini, New Delhi, India. Email: nikku1280@gmail.com

Introduction: Irreducible interphalangeal (IP) joint dislocation of the hallux is a rare injury, most often caused by interposition of the sesamoid–plantar plate complex. Diagnosis may be delayed due to subtle radiographs, and closed reduction is typically unsuccessful.

Materials and Methods: This retrospective case series reports six patients (ages 25–60 years, 4 males and 2 females) who sustained dorsal or plantar hallux IP dislocations following sports injuries, falls, or crush trauma during 2 years. Four patients presented acutely, while one presented 3 weeks after injury. Closed reduction failed in all cases. Open reduction was performed in all patients, with temporary Kirschner-wire fixation.

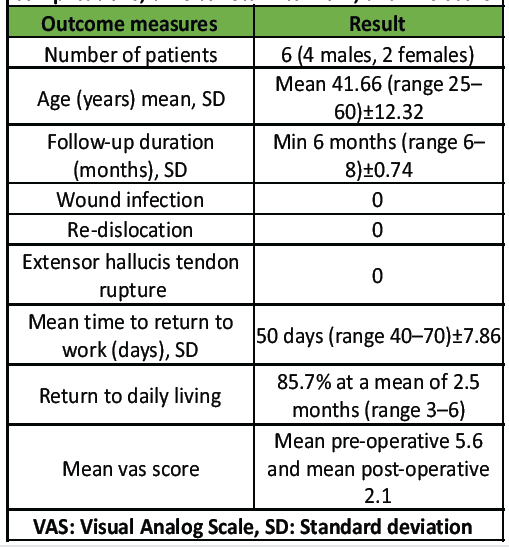

Results: No wound complications were noted; no extensor hallucis longus injuries were observed in any of the patients, and all of them healed well. The mean Visual Analog Scale (VAS) score pre-operative was 5.6, and the post-operative mean VAS score was 2.1; the mean time to return to work was 50 days. The follow-up (mean 6 months), four patients had full pain-free mobility, while two reported mild stiffness without functional limitation.

Conclusion: Irreducible hallux IP dislocations should be suspected when deformity persists after trauma. True-lateral radiographs are essential for diagnosis. Open or percutaneous reduction with temporary fixation provides reliable long-term outcomes.

Keywords: Hallux, interphalangeal joint, sesamoid, dislocation, open reduction, Kirschner-wire.

Dislocation of the great toe’s interphalangeal (IP) joint is an uncommon clinical entity, with most documented cases of great toe dislocations involving the metatarsophalangeal joint [1]. The relative rarity of IP joint dislocations is attributed to the intrinsic stability of the joint, which is reinforced by the strong plantar plate, collateral ligaments, and the sesamoid–plantar complex. When dislocations do occur, irreducible dorsal dislocations represent a particularly unusual subset [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8]. The patho-mechanics of these injuries are closely linked to the sesamoid–plantar plate complex. In cases of irreducible dislocation, this complex becomes incarcerated between the proximal and distal phalanges, preventing anatomical reduction. Miki et al. [3] provided a widely cited classification system, distinguishing between type I injuries, where the plantar plate–sesamoid complex is interposed within the IP joint, and type II injuries, where the complex is displaced dorsally over the proximal phalanx, resulting in a fixed hyperextension deformity. This classification remains clinically relevant, as it has direct implications for both diagnosis and surgical management. Closed reduction is the initial treatment of choice in the emergency setting; however, it often fails in irreducible cases due to mechanical obstruction by the sesamoid complex. Furthermore, delayed presentations are complicated by fibrosis, scarring, and capsuloligamentous attenuation, rendering late closed reductions ineffective [9]. As a result, open exploration and reduction are generally recommended when closed methods fail [10,11,12,13,14]. Various surgical strategies have been reported, ranging from open approaches to the dorsal and plantar aspects to minimally invasive or percutaneous techniques. In some cases, temporary fixation with Kirschner wires has been employed to maintain joint stability following reduction. Despite these reports, the overall literature on great toe IP joint dislocations remains sparse, consisting predominantly of isolated case reports and small case series. Consequently, there is no standardized consensus on the optimal management approach, and treatment is often individualized based on injury type, chronicity, and intraoperative findings. We report six cases of irreducible hallux IP dislocations, highlighting diagnostic challenges, surgical strategies, and long-term functional outcomes.

This retrospective series included six patients with irreducible IP joint dislocations of the hallux, which is a rare injury in itself. The study duration is 2 years, from August 2023 to July 2025. The mean age of presentation was 41.66, and the mean follow-up was 6 months (duration 6–8 months). The study was conducted after institutional clearance.

Inclusion criteria

All the patients present with IP joint dislocations of the hallux during the time period between August 2023 and July 2025. Age >18 years and <65 years.

Exclusion criteria

All the patients present with reducible IP joint dislocation and the age group <18 and >65 years.

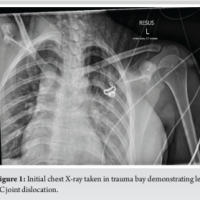

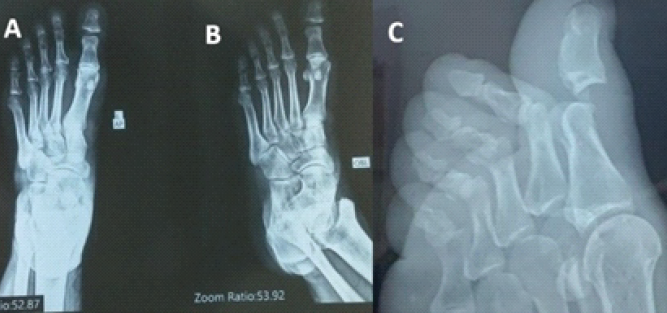

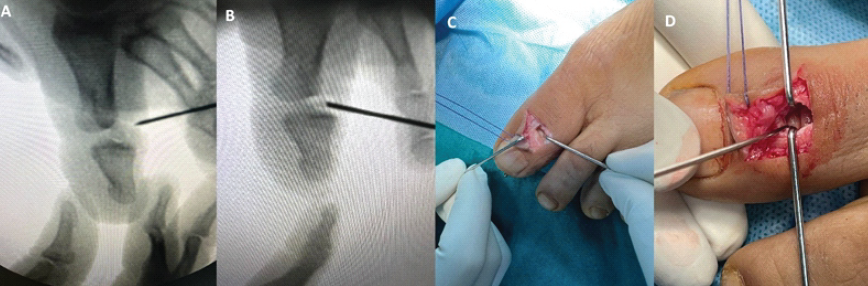

Mechanisms of injury included sports-related trauma, accidental falls, and workplace injuries. Four patients sustained acute injuries, while one presented 3 weeks after trauma with a neglected dislocation. All patients had visible deformity, swelling, and pain of the affected hallux. Standard radiographs confirmed dorsal type II dislocations in four cases and a plantar dislocation in one. True-lateral views were critical in detecting sesamoid incarceration in the delayed case. In all cases, closed reduction failed because the interposed sesamoid bone acted as a mechanical block, preventing congruent reduction of the IP joint. Open reduction was performed in all patients: through medial, dorsal, or L-shaped approaches, depending on chronicity and soft-tissue involvement. Temporary Kirschner-wire fixation was required in all cases to address capsuloligamentous instability. All procedures were performed by a single person (senior author). We present a case of Miki type II dorsal dislocation of the great toe IP joint with incarcerated sesamoid, demonstrating the stepwise approach and management. All the cases were dealt similarly, as described below. Here is an example of a case with a pre-operative radiograph as shown in Fig. 1.

Figure 1: This is a preoperative image of an interphalangeal joint dislocation of the great toe with an incarcerated sesamoid, as shown in anteroposterior, oblique, and lateral images of the left foot (a, b, c).

Surgical technique

Approach

The IP joint of the left hallux was accessed through a dorsal L-shaped incision, as shown in Fig. 2. The extensor expansion was incised longitudinally to provide adequate exposure of the joint. Care was taken to preserve the surrounding soft-tissue structures.

Figure 2: These are the intraoperative clinical images showing an L-shaped dorsal incision with the medial flap retracted with the help of Vicryl suture.

Intraoperative findings

Fluoroscopic evaluation confirmed a dorsal dislocation of the IP joint with an interposed sesamoid bone (Fig. 3a, b, c, d). On direct inspection, the sesamoid was visualized within the joint space, obstructing anatomical reduction.

Figure 3: These are the intraoperative clinical fluoroscopic and clinical images of an incarcerated sesamoid in between the interphalangeal joint of the great toe (a, b, c, d).

Procedure

The interposed sesamoid was carefully excised (Fig. 4). Subsequent intraoperative joint ranging confirmed the absence of bony or soft-tissue blocks. Despite this, spontaneous joint reduction was not achievable, likely due to periarticular soft-tissue contractures associated with the subacute presentation.

Figure 4: The intraoperative removal of the incarcerated sesamoid between the interphalangeal joint of the great toe.

Fixation and stabilization

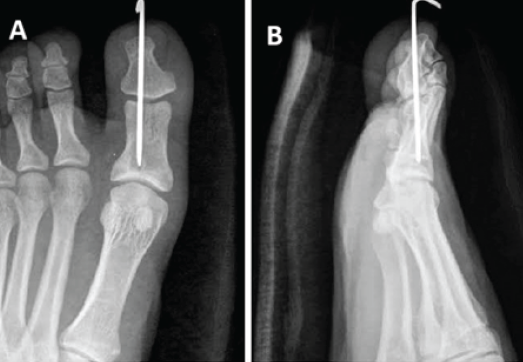

To maintain the reduction, temporary stabilization was performed. A 2.5 mm Kirschner-wire was inserted percutaneously across the IP joint under fluoroscopic guidance. Image intensification confirmed anatomical reduction and satisfactory alignment.

Closure

The extensor expansion was meticulously repaired to restore tendon continuity. Layered closure of the wound was performed, followed by the application of a sterile dressing. The hallux was immobilized postoperatively to protect fixation and facilitate healing, as shown in post-operative image (Fig. 5a and b). The mean K-wire removal time was 6–8 weeks. At a mean follow-up of 6 months (Fig. 6a and b), three patients had a full, pain-free range of motion, while two developed mild stiffness but were asymptomatic in daily activities. None had residual pain, instability, or recurrence of dislocation.

Figure 5: These are the post-operative images in anteroposterior and lateral view showing temporary fixation of the interphalangeal joint of the great toe with a 2.5 mm K-wire due to instability (a and b).

Figure 6: These are the 6 months post op images in anteroposterior and oblique view after K-wire removal with well-reduced interphalangeal joint of the great toe (a and b).

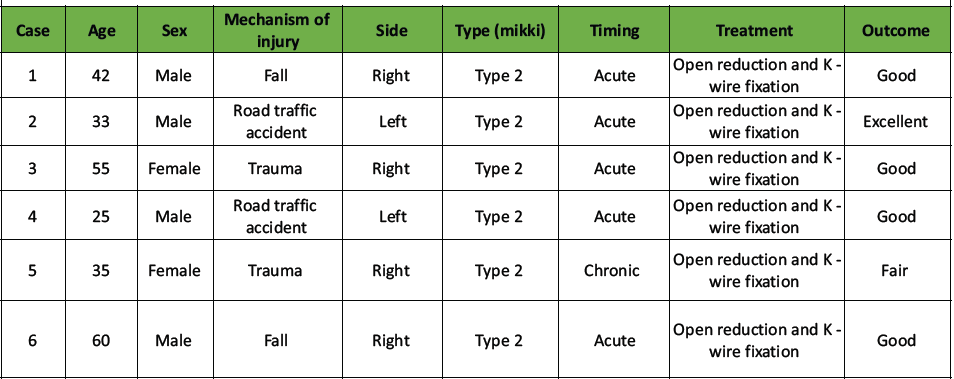

There were 6 patients in the case series: 4 males and 2 females of an age range of 25–60, who sustained dorsal or plantar hallux IP dislocations following sports injuries, falls, or crush trauma. Five patients presented acutely, while one presented 3 weeks after injury between August 2023 and July 2025. Closed reduction failed in all cases. Open reduction was performed in all patients, with temporary Kirschner-wire fixation. There were no recorded complications related to the procedure. Specifically, there were no cases of wound infection, extensor hallucis longus tendon rupture, or any other complication observed in this series. The pre-operative Visual Analog Scale (VAS) score was 5.6 (mean) and the post-operative VAS score was 2.1 (mean). The mean time to return to work was 50 days, with a range of 40–70 days. Indicating good-to-excellent functional outcomes across the study. The outcomes were graded (fair, good, excellent) based on clinical parameters (pain, range of motion, and joint stability), radiological evaluation, and joint congruity at the final follow-up. The summary is mentioned in Tables 1 and 2.

Table 1: A summary of the patients, mechanism of injury, classification, timing of presentation, treatment, and outcome

Table 2: A summary of follow-up duration, any complications, time to return to work, and VAS score

Irreducible IP dislocations of the hallux remain uncommon, with fewer than 50 cases reported in the English-language literature. The primary obstacle to reduction is entrapment of the sesamoid–plantar plate complex. Dorsal dislocation of the IP joint of the hallux is an uncommon injury. The anatomical configuration of the joint renders closed reduction challenging [15]. Suwannahoy et al. [16] performed a cadaveric analysis of 100 fresh halluces to characterize the morphology, quantity, dimensions, and positioning of intra-articular ossicles within the IP joint space. Radiographic evaluation indicated that 86% of identified bony masses were either sesamoid bones or intra-articular ossicles. Notably, 88% of these bony structures were located on the dorsal aspect of the plantar capsule of the IP joint. The difficulty in achieving closed reduction is likely attributable to the interposition of the plantar capsule with the sesamoid, as inferred from the findings of Suwannahoy et al. [16]. In the present cases, initial radiographs obtained at the emergency department were less indicative of a hallux IP joint dislocation compared to subsequent imaging. This observation aligns with findings by Miki et al. [3], who noted that in up to 44% of cases, the IP sesamoid is radiographically occult, complicating the diagnosis of sesamoid interposition and verification of successful reduction. In our patient, the dislocation was not identified on initial imaging, which included only dorsoposterior and oblique views of the hallux (Fig. 1). Given the rarity of this condition, we recommend acquiring both dorsoposterior and true lateral radiographic views when clinical findings suggest a potential hallux dislocation. Open reduction is indicated following unsuccessful attempts at closed reduction. The literature describes both dorsal [2,3,6] and medial [11,12] surgical approaches. In the dorsal approach, the extensor tendon may be retracted laterally or longitudinally divided, as was performed in our patient, with the latter technique providing enhanced surgical exposure [6]. Miki et al. [3] provided a comprehensive analysis of the hallux anatomy and its sesamoid, identifying key features: (1) the robust plantar plate is distinct from the flexor hallucis longus tendon and is prone to displacement into the joint space; (2) the sesamoid is nearly fully embedded within the plantar plate, enabling the sesamoid-plantar plate complex to function as a unified structure; (3) fibrous connections link the plantar plate to the proximal and distal phalanges, stabilizing against dislocation; (4) the plantar plate remains outside the joint space if its attachment to either the proximal or distal phalanx is preserved; and (5) dislocation of the plantar plate into the joint space requires disruption of both proximal and distal phalangeal attachments. Based on this anatomical framework, IP joint dislocations are classified into two types. Type-I dislocations involve the sesamoid-plantar plate complex slipping into the IP joint, causing mild elongation of the hallux without significant deformity. In type-II dislocations, the complex displaces plantarly, emerges dorsally, and overrides the proximal phalanx head, resulting in a hyperextension deformity of the distal phalanx. All our patients exhibited a type-II dislocation. Clinical and radiographic assessments distinguish these types. In type-I dislocations, the distal phalanx maintains a neutral position with resistance to both dorsiflexion and plantarflexion, and radiographs reveal the sesamoid within a widened joint space with coaxial phalanges. In type-II dislocations, the distal phalanx is hyperextended with minimal resistance to dorsiflexion, and radiographs show the sesamoid dorsal to the proximal phalanx head with a hyperextended distal phalanx. In both types, reduction is challenging due to intact collateral ligaments, as observed in our patient on presentation to our clinic. Following open reduction of the IP joint in our patient, the joint exhibited increased laxity, attributable to overstretching of the joint capsule and collateral ligaments during the initial trauma [3,6]. In accordance with Woon’s recommendation [8], we opted for temporary stabilization using Kirschner-wire fixation. Alternative stabilization techniques reported in the literature include the application of a bulky dressing [2], buddy taping [11], and immobilization in a short leg cast [3] for up to 4 weeks. We elected to immobilize the IP joint for 6 weeks before Kirschner-wire removal and initiation of mobilization. Leung and Wong [6] noted that, following Kirschner-wire extraction, recurrent dislocation is infrequent, and the long-term prognosis is favorable. We had a similarly positive outcome for our patients.

Fixation and outcomes

Temporary Kirschner-wire fixation is recommended when instability persists after reduction. Excision of an incarcerated sesamoid did not impair functional outcomes in our series. Although delayed presentations increase the risk of stiffness, satisfactory pain-free function is still achievable with timely surgical management.

Irreducible hallux IP joint dislocation is a rare but significant injury. Sesamoid interposition should be suspected when closed reduction fails. True-lateral radiographs are critical for diagnosis. Open or percutaneous reduction with temporary fixation provides reliable long-term outcomes.

Dislocation of the IP joint of the great toe is rare and may be missed due to subtle radiographic findings. A high index of suspicion is essential for diagnosis. While closed reduction is preferred, irreducible cases often require open reduction with or without internal fixation.

References

- 1. Hatori M, Goto M, Tanaka K, Smith RA, Kokubun S. Neglected irreducible dislocation of the interphalangeal joint of the great toe: A case report. J Foot Ankle Surg 2006;45:271-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 2. Nelson TL, Uggen W. Irreducible dorsal dislocation of the interphalangeal joint of the great toe. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1981;157:110-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 3. Miki T, Yamamuro T, Kitai T. An irreducible dislocation of the great toe. Report of two cases and review of the literature. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1988;230:200-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 4. Yasuda T, Fujio K, Tamura K. Irreducible dorsal dislocation of the interphalangeal joint of the great toe: Report of two cases. Foot Ankle 1990;10:331-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 5. Dave D, Jayaraj VP, James SE. Intra-articular sesamoid dislocation of the interphalangeal joint of the great toe. Injury 1993;24:198-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 6. Leung HB, Wong WC. Irreducible dislocation of the hallucal interphalangeal joint. Hong Kong Med J 2002;8:295-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 7. Sorene ED, Regev G. Complex dislocation with double sesamoid entrapment of the interphalangeal joint of the hallux. J Foot Ankle Surg 2006;45:413-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 8. Woon CY. Dislocation of the interphalangeal joint of the great toe: Is percutaneous reduction of an incarcerated sesamoid an option?: A report of two cases. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2010;92:1257-60. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 9. Jahss MH. Stubbing injuries to the hallux. Foot Ankle 1981;1:327-32. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 10. Eibel P. Dislocation of the interphalangeal joint of the big toe with interposition of a sesamoid bone. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1954;36-A:880-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 11. Crosby LA, McClellan JW 3rd, Prochaska VJ. Irreducible dorsal dislocation of the great toe interphalangeal joint: Case report and literature review. Foot Ankle Int 1995;16:559-61. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 12. Kursunoglu S, Resnick D, Goergen T. Traumatic dislocation with sesamoid entrapment in the interphalangeal joint of the great toe. J Trauma 1987;27:959-61. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 13. Imao K, Miwa H, Watanabe K, Imai N, Endo N. Dorsal-approach open reduction for irreducible dislocation of the hallux interphalangeal joint: A case series. Int J Surg Case Rep 2018;53:316-21. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 14. Wolfe J, Goodhart C. Irreducible dislocation of the great toe following a sports injury. A case report. Am J Sports Med 1989;17:695-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 15. Ward SJ, Sheridan RP, Kendall IG. Sesamoid bone interposition complicating reduction of a hallux joint dislocation. J Accid Emerg Med 1996;13:297-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 16. Suwannahoy P, Srisuwan T, Pattamapaspong N, Mahakkanukrauh P. Intra-articular ossicle in interphalangeal joint of the great toe and clinical implication. Surg Radiol Anat 2012;34:39-42. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]