The extensile direct anterior approach is a viable and effective option for complex acetabular revisions using an anti-protrusion cage, allowing for adequate exposure, component stability, and early mobilization

Dr. Giacomo Moraca, Department of Orthopaedics and Traumatology, Lugano Regional Hospital, Via Tesserete 46, 6900 Lugano, Switzerland. E-mail: moraca.giacomo@gmail.com

Introduction: Periprosthetic acetabular fractures following total hip arthroplasty (THA) represent a rare but challenging condition, particularly in patients with previous surgeries through the direct anterior approach (DAA). The case described is, to our knowledge, the first report of a central dislocation of the acetabular component treated using a Burch–Schneider anti-protrusion cage through an extensile DAA. This surgical choice was aimed at minimizing instability and optimizing exposure in a complex revision setting, thus offering an innovative contribution to the orthopedic literature.

Case Report: A 64-year-old Caucasian female affected by ischemic vascular transverse myelopathy leading to asymmetric paraparesis, with greater involvement of the right lower limb, presented after a fall on her previously operated left hip. She underwent THA 2 years earlier. Radiological evaluation revealed a transverse acetabular fracture with medial cup migration and an associated Vancouver AG fracture. Given the patient’s reliance on the left limb for mobility and the risks of instability from multiple surgical approaches, the revision was performed through an extensile DAA. An antiprotrusio cage specifically designed for anterior implantation was used, and the femoral component was preserved. Early mobilization was initiated postoperatively, with the patient regaining pre-injury mobility within 6 months.

Conclusion: This case demonstrates the feasibility and benefits of using the extensile DAA in managing complex acetabular defects with a Burch–Schneider antiprotrusio cage. It highlights a surgical strategy that may reduce the risk of instability and improve functional outcomes in selected patients. The originality of this case lies in the use of an anterior approach to address a complication with a reconstruction technique typically reserved for posterior approaches. This report contributes to expanding the surgical options in revision hip arthroplasty and provides new insights into optimizing care in patients with complex anatomical and functional constraints.

Keywords: Hip, prosthesis, acetabular fracture, revision, extensile direct anterior approach, antiprotrusio cage.

The incidence of primary total hip arthroplasty (THA) has been rising significantly, leading to a dramatic increase in THA revisions, a trend expected to continue in direct proportion to the exponential growth of primary THA in the upcoming decades [1,2,3]. Despite advancements in surgical technique and technology, revision THA for large acetabular defects remains challenging, even for the most experienced arthroplasty surgeons. In many cases, limited host bone stock hinders the conventional implantation of stable prosthetic components [4]. The antiprotrusio cage was developed to address cases of acetabular bone loss or fractures and has proven to be an effective technique for specific patterns of acetabular deficiency [5].

Revision THA through various surgical approaches, such as the posterior, modified Hardinge, and modified Watson–Jones, has been well documented in the literature [6,7]. Over the past 15 years, the direct anterior approach (DAA) performed through the Smith–Petersen interval has gained increasing popularity [8,9,10]. The extensile version of the DAA has further broadened its indications to include revision hip surgeries [11]. Understanding and being able to perform the extensile DAA is also crucial in primary THA when intraoperative complications arise [12,13]. However, few studies have evaluated its effectiveness in the context of revision arthroplasty [14,15,16]. Moreover, unlike other well-established surgical hip approaches, there is a paucity of literature on post-operative recovery as well as both short- and long-term clinical outcomes following extensile DAA for revision THA.

Our practice has evolved to adopt the DAA as a versatile approach that offers extensile capabilities by providing adequate acetabular and femoral exposure, even in complex cases. Nevertheless, achieving extensile exposure through the DAA can be technically demanding, depending on patient-specific factors and the surgeon’s level of experience. Careful patient selection is therefore crucial for success, particularly during the learning curve of this approach.

In this paper, we present a case of central dislocation of the acetabular component in a THA. As the primary arthroplasty was performed by the DAA, we chose to revise the acetabular component through an extensile DAA to minimize the risk of instability associated with multiple surgical approaches to the hip. To our knowledge, this is the first reported case in the literature of central dislocation treated with a Burch–Schneider cage through the DAA.

A 64-year-old female with asymmetric paraparesis due to ischemic vascular transverse myelopathy presented to our clinic following trauma to her left hip. She underwent THA 2 years earlier after a femoral neck fracture. The index procedure consisted of a dual mobility THA, with excellent post-operative outcomes and no complications at the established follow-up.

Ischemic vascular transverse myelopathy is a rare spinal cord disorder caused by impaired blood supply to the medullary segments, leading to variable motor, sensory, and autonomic dysfunction depending on the level involved [17]. In this patient, the lesion, diagnosed in 2012, affected the D11-L1 segments and resulted in asymmetric paraparesis with predominant weakness of the right lower limb and sensory impairment below L1. The patient also suffered from a right equinus foot deformity, for which she underwent Achilles tendon lengthening surgery in 2016, followed by botulinum toxin injections. She further presented with a neurological lower urinary tract dysfunction characterized by autonomic dysregulation, hypocontractile low-pressure bladder, neurogenic bowel, and sexual dysfunction. Aside from her neurological condition, the patient was otherwise in good general health. She was wheelchair-bound but also used a rolling walker, relying primarily on her left leg for ambulation and transfers, as it was her stronger, weight-bearing limb.

She presented to our emergency department after falling on her left hip while using a rolling walker. On examination, the left leg appeared shortened, with range of motion not assessable and no distal neurovascular deficits.

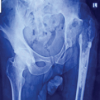

Radiographic evaluation, including computed tomography, revealed the protrusion of the acetabular cup into the pelvis, associated with a transverse acetabular fracture and a Vancouver AG-type fracture (Figs. 1 and 2).

Figure 1: Pre-operative pelvis antero-posterior X-ray.

Figure 2: Pre-operative pelvis computed tomography scan.

The prior THA was implanted through a DAA, so we decided to avoid additional surgical approaches due to the high risk of instability, particularly in a patient reliant on a wheelchair and at risk for complications from dual incisions.

We planned the use of an antiprotrusio cage (3D Metal-B Cage, Medacta), specifically designed to facilitate implantation through the anterior approach. This implant features a biomaterial structure that provides a robust construct, promotes bone ingrowth, and combines lag screws with polyaxial locking screws capable of delivering compression.

The DAA was performed with the patient in the supine position on a traction operating table, with only the left leg prepped and draped. A standard skin incision was made from a point midway between the anterior superior iliac spine (ASIS) and the tip of the greater trochanter. For extensile acetabular procedures, the incision was extended proximally to the ASIS and then continued laterally along the iliac crest. Careful cauterization of the perforating branches of the lateral femoral circumflex vessels was carried out to prevent bleeding complications, with particular attention paid to avoiding injury to the terminal inferior branch of the superior gluteal nerve (SGN) [18].

Deep proximal dissection was carried out through the interval between the rectus femoris and the gluteus medius. Palpation of the superior femoral neck through this interval was used to guide the positioning of a Charnley retractor, placed medially over the superior capsule and laterally over the tensor fasciae latae (TFL).

A curved Hohmann-style retractor was then placed inferiorly and medially over the capsule surrounding the femoral neck. A Cobb elevator was then used to sweep the rectus femoris off the anterior capsule medially, down to the level of the anterior column, while adhesions were released using electrocautery. A second curved Hohmann-style retractor was placed superior to the femoral neck. An arthrotomy was performed from the acetabular rim to the intertrochanteric line, inferior to the neck. The capsule was then released superiorly from both the acetabulum and the femur, and subsequently locked under the lateral blade of the Charnley retractor to protect the TFL. The inferior and superior Hohmann retractors were then repositioned within the capsule.

At this stage, in revision cases where the femoral stem is retained, the femur is typically dislocated using traction, external rotation, and a bone hook, followed by removal of the femoral head. Elevating the foot allows the femoral neck to shift posteriorly, facilitating placement of a retractor behind the acetabulum to gain full acetabular exposure and retract the femur posteriorly. In our case, after dislocation and removal of the femoral head, the femoral stem was found to be stable; therefore, we proceeded without stem removal. However, the patient also presented with a Vancouver AG fracture, which required a more extensive proximal exposure. To achieve this, the TFL was released from the anterior ilium to allow posterior mobilization of the femur for cage placement and to facilitate fixation of the greater trochanter following acetabular reconstruction.

The outer surface of the iliac wing was exposed in a subperiosteal fashion, and partial release of the TFL was necessary to achieve adequate exposure for placement of the cage or its flange on the ilium. In addition, when needed, the inner surface of the iliac wing can be accessed by releasing the sartorius and inguinal ligament from the ASIS, followed by subperiosteal elevation of the iliacus from the internal aspect of the iliac crest. Further extension into the inner table of the acetabulum can be accomplished by releasing the rectus femoris from the anterior inferior iliac spine, allowing full exposure of the acetabulum and anterior column.

Inferiorly, subperiosteal dissection was carried out along the pubis and ischium until adequate exposure was obtained. This was maintained with careful placement of Hohmann retractors, anteriorly above the pubis and posteriorly along the ischium, ensuring that the retractor tips remained on bone to avoid any possible contact with the sciatic nerve. The acetabulum was prepared by lightly reaming until bleeding bone was achieved. The site for the ischial flange was prepared from the internal aspect of the acetabulum, and the implant was inserted by impacting the inferior flange into the ischial bone. Once the cage was well seated, superior acetabular screws were placed through the superior flange into the ilium. The acetabular cup was then cemented into the cage. Based on trial reduction and intraoperative stability, the appropriate femoral neck length was selected, with careful attention to restoring leg length and joint stability. A dual mobility bearing was chosen to minimize the risk of post-operative dislocation.

Finally, the greater trochanter was fixed with K-wires and a figure-of-eight cerclage. During surgery, the patient lost approximately 800 mL of blood and received two units of packed red blood cells intraoperatively, followed by one additional unit postoperatively. Her post-operative course was otherwise uneventful. She began full weight bearing on post-operative day 1 and was transferred to a rehabilitation facility on day 9.

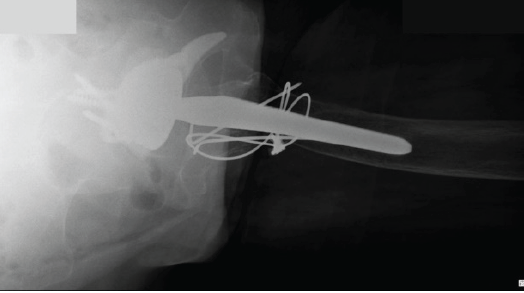

At 8 weeks postoperatively, the patient was pain-free, with a range of motion of 0–100° flexion, 30° abduction, 30° adduction, 30° internal rotation, and 30° external rotation. She had successfully resumed mobility, taking several steps with the assistance of a wheeled walker. At the 6-month follow-up, the patient reported walking and moving as she did before the trauma and surgery. Radiographic evaluation at that time confirmed implant stability and showed signs of bony consolidation of the greater trochanter (Figs. 3 and 4).

Figure 3: Six months post-operative pelvis antero-posterior X-ray.

Figure 4: Six months post-operative axial hip X-ray.

With the rising popularity of the DAA for primary THA over the past two decades, there has been increasing interest in its application in revision settings. Revision THA is well known to carry significantly higher complication rates compared to primary procedures. Among these, dislocation is the most common complication, often attributed to greater soft-tissue damage and post-operative scarring, which can lead to muscle weakness [19,20]. The posterior approach, in particular, has been associated with higher rates of post-operative dislocation in revision surgery when compared to the DAA [18,19,21,22,23].

Soft-tissue dissection of the abductor musculature to achieve acetabular exposure carries risks not only of muscle damage but also of nerve injury. The posterior approach involves a gluteal split, which may place the SGN at risk due to traction. In contrast, the extensile DAA employs a gluteal elevation technique to access the outer table of the ilium, thereby avoiding SGN traction and potentially reducing the risk of nerve injury [24]. In addition, the sciatic nerve is more at risk with the posterior approach, with higher reported rates of post-operative palsy compared to the anterior approach. On the other hand, the DAA is associated with a higher incidence of femoral nerve palsy [24].

Another advantage of the anterior approach in the revision setting is the excellent acetabular exposure it provides. The minimally invasive DAA can offer sufficient visualization for liner exchanges and selected cup revisions [12]. For more complex acetabular reconstructions, the extensile DAA can be employed, with proximal extension achieved through tenotomy of the TFL at its origin and subperiosteal elevation of the abductor musculature. Supine positioning, as used in the DAA, also offers intraoperative advantages. With the patient placed supine on a standard operating table, both legs can be prepped and draped, allowing for accurate intraoperative assessment of leg length. Furthermore, intraoperative fluoroscopy enables precise evaluation of cup and screw positioning, as well as radiographic assessment of leg length and offset [25,26].

Moreover, in the revision setting, the preservation of both the posterior capsule and external rotators may offer an advantage by reducing the risk of post-operative complications, especially in patients who have already undergone anterior capsulotomy during primary THA through DAA.

Severe acetabular defects and periprosthetic acetabular fractures remain among the greatest challenges in revision hip reconstruction. Several implant options are available to address substantial bone loss, including highly porous hemispherical cups, metal acetabular augments combined with revision shells, antiprotrusio cages, custom triflange components, and cup-cage constructs. Despite this wide range of available solutions, there is no established consensus regarding the optimal implant choice. Instead, surgeon experience, clinical judgment, and patient-specific factors, such as defect morphology and bone quality, continue to guide individualized decision-making in complex revision scenarios.

The Burch–Schneider antiprotrusio cage (BS-APC), as used in the presented case, represents a reliable option for the management of medial acetabular defects, particularly Paprosky type 3A and 3B, where other cages with medial fixation hooks (such as the Ganz or Kerboull cage) may not be feasible [27,28]. The BS-APC has shown favorable results when compared to other devices, particularly in terms of long-term implant survival rates [29,30]. In contrast to this, a recent review by Malahias et al. analyzed 374 cases treated with BS-APCs. They reported a short-term survival rate of 90.6% (339 out of 374 cases), a mid-term survival rate of 85.6% (320 out of 374 cases), and a long-term survival rate of 62% (54 out of 87 cases) [31]. The relatively high failure rate observed in the long term (38%) was attributed to the lack of biological fixation provided by antiprotrusio cages. Based on these findings, the authors concluded that routine use of modern BS-APCs in complex revision THA may not be recommended. Despite these concerns, in our experience, BS-APCs remain a valuable option in selected cases. We believe that the satisfactory short- to mid-term outcomes, combined with the significantly lower cost compared to highly porous acetabular implants, support their use in carefully selected patients. In particular, we consider BS-APCs to be a reasonable option in elderly or low-demand individuals who do not present with severe superomedial acetabular bone loss. Furthermore, when a structural allograft is used in conjunction with the cage, even if the reconstruction eventually fails, re-revision surgery with an uncemented acetabular component may still be feasible once the allograft has fully incorporated [32].

The presented case highlighted the feasibility of using an extensile DAA for complex acetabular revision in the setting of central dislocation with severe medial bone loss. The use of a BS-APC through the DAA allowed for adequate exposure, stable reconstruction, and early mobilization in a patient with significant comorbidities. While long-term outcomes of anti-protrusio cages remain variable, this technique may represent a valuable and cost-effective option in selected low-demand patients, particularly when anatomical constraints or prior approaches limit surgical alternatives.

This case highlights the effectiveness of the extensile DAA for complex acetabular revisions, suggesting it as a valuable alternative to traditional approaches. Its adoption may reduce surgical morbidity and improve outcomes in selected revision THA cases.

References

- 1. Bozic KJ, Kurtz SM, Lau E, Ong K, Vail TP, Berry DJ. The epidemiology of revision total hip arthroplasty in the United States. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2009;91:128-33. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 2. Kurtz S, Mowat F, Ong K, Chan N, Lau E, Halpern M. Prevalence of primary and revision total hip and knee arthroplasty in the United States from 1990 through 2002. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2005;87:1487-97. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 3. Sloan M, Premkumar A, Sheth NP. Projected volume of primary total joint arthroplasty in the U.S., 2014 to 2030. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2018;100:1455-60. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 4. Morgan S, Bourget-Murray J, Garceau S, Grammatopoulos G. Revision total hip arthroplasty for periprosthetic fracture: Epidemiology, outcomes, and factors associated with success. Ann Jt 2023;8:30. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 5. Marx A, Beier A, Richter A, Lohmann CH, Halder AM. Major acetabular defects treated with the Burch-Schneider antiprotrusion cage and impaction bone allograft in a large series: A 5- to 7-year follow-up study. Hip Int 2016;26:585-90. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 6. Kerboull L. Selecting the surgical approach for revision total hip arthroplasty. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res 2015;101:S171-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 7. Masterson EL, Masri BA, Duncan CP. Surgical approaches in revision hip replacement. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 1998;6:84-92. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 8. Barrett WP, Turner SE, Leopold JP. Prospective randomized study of direct anterior vs postero-lateral approach for total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 2013;28:1634-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 9. Connolly KP, Kamath AF. Direct anterior total hip arthroplasty: Comparative outcomes and contemporary results. World J Orthop 2016;7:94-101. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 10. Post ZD, Orozco F, Diaz-Ledezma C, Hozack WJ, Ong A. Direct anterior approach for total hip arthroplasty: Indications, technique, and results. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 2014;22:595-603. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 11. Kennon R, Keggi J, Zatorski LE, Keggi KJ. Anterior approach for total hip arthroplasty: Beyond the minimally invasive technique. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2004;86-A Suppl 2:91-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 12. Mast NH, Laude F. Revision total hip arthroplasty performed through the Hueter interval. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2011;93 Suppl 2:143-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 13. Thaler M, Dammerer D, Krismer M, Ban M, Lechner R, Nogler M. Extension of the direct anterior approach for the treatment of periprosthetic femoral fractures. J Arthroplasty 2019;34:2449-53. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 14. Honcharuk E, Kayiaros S, Rubin LE. The direct anterior approach for acetabular augmentation in primary total hip arthroplasty. Arthroplast Today 2018;4:33-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 15. Manrique J, Chen AF, Heller S, Hozack WJ. Direct anterior approach for revision total hip arthroplasty. Ann Transl Med 2014;2:100. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 16. Nogler MM, Thaler MR. The direct anterior approach for hip revision: Accessing the entire femoral diaphysis without endangering the nerve supply. J Arthroplasty 2017;32:510-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 17. Zalewski NL. Vascular myelopathies. Continuum (Minneap Minn) 2021;27:30-61. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 18. Alberton GM, High WA, Morrey BF. Dislocation after revision total hip arthroplasty: An analysis of risk factors and treatment options. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2002;84:1788-92. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 19. Faldini C, Stefanini N, Fenga D, Neonakis EM, Perna F, Mazzotti A, et al. How to prevent dislocation after revision total hip arthroplasty: A systematic review of the risk factors and a focus on treatment options. J Orthop Traumatol 2018;19:17. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 20. Horsthemke MD, Koenig C, Gosheger G, Hardes J, Hoell S. The minimal invasive direct anterior approach in aseptic cup revision hip arthroplasty: A mid-term follow-up. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2019;139:121-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 21. Fackler CD, Poss R. Dislocation in total hip arthroplasties. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1980;151:169-78. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 22. Hailer NP, Weiss RJ, Stark A, Kärrholm J. The risk of revision due to dislocation after total hip arthroplasty depends on surgical approach, femoral head size, sex, and primary diagnosis. An analysis of 78,098 operations in the Swedish Hip Arthroplasty Register. Acta Orthop 2012;83:442-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 23. Wetters NG, Murray TG, Moric M, Sporer SM, Paprosky WG, Della Valle CJ. Risk factors for dislocation after revision total hip arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2013;471:410-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 24. Slaven SE, Ho H, Sershon RA, Fricka KB, Hamilton WG. Motor nerve palsy after direct anterior versus posterior total hip arthroplasty: Incidence, risk factors, and recovery. J Arthroplasty 2023;38:S242-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 25. Chen P, Liu W, Wu C, Ruan P, Zeng J, Ji W. Fluoroscopy-guided direct anterior approach total hip arthroplasty provides more accurate component positions in the supine position than in the lateral position. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2023;24:884. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 26. Ji W, Stewart N. Fluoroscopy assessment during anterior minimally invasive hip replacement is more accurate than with the posterior approach. Int Orthop 2016;40:21-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 27. Kerboull M, Hamadouche M, Kerboull L. The Kerboull acetabular reinforcement device in major acetabular reconstructions. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2000;378:155-68. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 28. Tanaka C, Shikata J, Ikenaga M, Takahashi M. Acetabular reconstruction using a Kerboull-type acetabular reinforcement device and hydroxyapatite granules: A 3- to 8-year follow-up study. J Arthroplasty 2003;18:719-25. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 29. Coscujuela-Mañá A, Angles F, Tramunt C, Casanova X. Burch-Schneider antiprotrusio cage for acetabular revision: A 5- to 13-year follow-up study. Hip Int 2010;20 Suppl 7:S112-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 30. Wachtl SW, Jung M, Jakob RP, Gautier E. The Burch-Schneider antiprotrusio cage in acetabular revision surgery: A mean follow-up of 12 years. J Arthroplasty 2000;15:959-63. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 31. Malahias MA, Sarantis M, Gkiatas I, Jang SJ, Gu A, Thorey F, et al. The modern Burch-Schneider antiprotrusio cage for the treatment of acetabular defects: Is it still an option? A systematic review. Hip Int 2023;33:705-15. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 32. Hsu CC, Hsu CH, Yen SH, Wang JW. Use of the Burch-Schneider cage and structural allografts in complex acetabular deficiency: 3- to 10-year follow up. Kaohsiung J Med Sci 2015;31:540-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]