Isolated Zone 3 flexor digitorum profundus ruptures can mimic Zone 1 “Jersey finger” injuries clinically, prompt imaging to localize and early direct repair yield the best functional outcomes.

Dr. Nirav Mungalpara, Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, University of Illinois Chicago, Chicago, Illinois. E-mail: nirav@uic.edu

Introduction: Isolated rupture of the flexor digitorum profundus tendon within flexor zone 3 is exceptionally rare and easily mistaken for the far more common zone 1 “Jersey finger” lesion. To the best of our knowledge, only two such middle-finger cases have been documented over the past six decades. Reporting this case, together with a literature synthesis, highlights the diagnostic pitfalls and supports timely, tendon-preserving intervention.

Case Report: A 65-year-old right-hand-dominant White male felt a sudden snap in his right palm while restraining a dog leash, followed by an inability to flex the distal interphalangeal joint of the middle finger. Clinical examination showed loss of the tenodesis effect, but plain radiographs excluded fracture. Initial exploration aimed at tendon reinsertion in zone 1 revealed an intact insertion, prompting proximal extension of the incision. A complete mid-substance rupture was identified in zone 3, approximately one centimeter proximal to the origin of the lumbrical muscle. Primary repair was performed using a four-strand cruciate core technique reinforced with circumferential epitendinous sutures. Post-operative rehabilitation employed early-motion protocols. Twelve months after surgery, the patient regained full strength, achieved a total active finger motion of 230°, and reported 95 percent functional recovery.

Conclusion: This case illustrates how a concealed zone 3 rupture can masquerade as a distal avulsion, emphasizing the need for high clinical suspicion and, when feasible, pre-operative ultrasonography or magnetic resonance imaging to guide incision planning. Early direct repair within days of injury provided an excellent functional result, underscoring that prompt recognition prevents unnecessary grafting or transfer procedures. By adding the first modern case of isolated middle-finger zone 3 rupture and proposing a minimum reporting dataset, this report broadens surgeons’ awareness of an uncommon injury and supports evidence-based management strategies that may preserve grip strength and hand function across orthopedic practice.

Keywords: Tendon injury, flexor zone 3 of hand, tendon repair, tendon transfer, tendon graft, flexor digitorum profundus.

Flexor digitorum profundus (FDP) tendon ruptures are one of the most common injuries in hand surgery practices. The most common traumatic FDP tendon injuries are those that involve the insertion of the tendon (zone 1), with or without a bony avulsion fragment. It is also commonly termed ‘Jersey finger’ [1]. Compared to Zone 1, intrasubstance FDP ruptures in other zones are rare and, as a result, frequently misdiagnosed at initial presentation. Unlike insertional tears, which typically occur in otherwise healthy tendons, mid-substance tears are typically associated with underlying pathologic conditions. Extrinsic causes of rupture include irregularities in the carpus, such as fracture, tumor, osteoarthritis, and inflammatory arthritis, which can cause the tendon to fray against uneven surfaces or bone spikes, leading to rupture due to attrition [2,3,4,5]. Intrinsic causes for rupture are intratendinous steroid injections or diminished tendon vascularity and nutrition, leading to intratendinous weakening of the tendon [6,7,8]. Tendon rupture secondary to inflammation is often associated with swelling in adjacent joints and soft tissues, such as in uncontrolled rheumatoid arthritis. Medications, such as fluoroquinolones, have been linked to a higher risk of developing tendinopathy and tendon rupture, although the precise mechanisms behind it is unclear. Researchers have noted microscopic structural changes associated with such cases [9].

In 1960, Boyes et al. [10] published a series of 80 cases of intrasubstance flexor tendon ruptures in 78 patients, spanning a 13 years. Remarkably, only three cases were documented without an identifiable etiology. Among these, two were localized in Zone 3. The author proposed the term “spontaneous” for those ruptures that occur without any underlying or associated pathological changes. However, the definitions of “spontaneous rupture” are imprecise and vary among authors who have reported this injury afterwards. Recently, Bickley et al. [11] reported a case and literature review of flexor tendon injuries occurring outside Zone 1. To date, no comprehensive review has been published that focuses on flexor tendon injuries occurring specifically within Zone 3.

In this article, we describe a representative case of rupture of the FDP in Zone 3 of the middle finger, accompanied by a comprehensive review of literature on all documented Zone 3 flexor tendon injuries from 1960 to 2025.

A 65-year-old right-hand-dominant male presented with sudden-onset pain and inability to actively flex the right middle finger distal interphalangeal (DIP) joint. The mechanism was described as a sudden eccentric force on a flexed middle finger while holding a dog leash, during which he felt a sudden “pop” in the hand and immediately noted the above symptoms. He denied a history of antecedent hand pain, fracture, inflammatory arthritis, repetitive injury, or tendon-toxic medication use. On examination, the patient was unable to actively flex the DIP joint and had an absent tenodesis effect on the middle finger with passive wrist extension, indicating FDP disruption. He had tenderness diffusely about the middle finger and the palm at a location just proximal to the likely location of the A1 pulley. He was able to actively flex the proximal interphalangeal (PIP) joint, indicating an intact flexor digitorum superficialis (FDS) tendon. The neurovascular examination was normal. Multiple radiographic views of the hand and finger were negative for fractures. Our initial working diagnosis was an Leddy-Packer Type I Zone 1 flexor tendon avulsion, which carries a risk of tendon retraction into the palm. Given the potential for vascular compromise with delayed intervention, pursuing advanced imaging would have delayed surgical repair. Therefore, a prompt plan for surgical exploration and FDP tendon reinsertion was established after thorough discussion with the patient. Three days after the injury, the patient was taken to the operating room after getting necessary clearance.

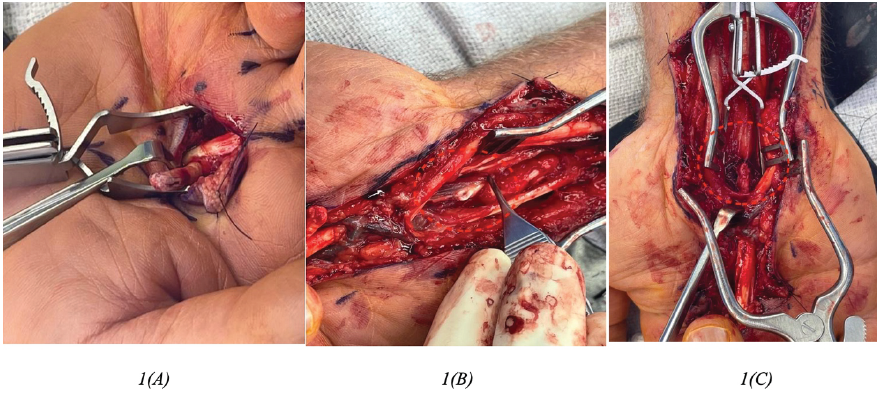

Under regional anesthesia, a Bruner incision was made over the DIP joint of the middle finger, which revealed an intact FDP insertion. Given that Leddy-Packer Type I Zone 1 avulsions are more common and can present with diffuse tenderness, initial exploration was appropriately initiated at the DIP level. A more proximal injury to the FDP tendon was suspected. The patient and his family were intraoperatively notified of these findings and recommended proximal exploration and repair of the FDP tendon. After obtaining consent from both the patient and his wife, a Bruner incision was made over the A1 pulley of the middle finger. The A1 pulley and the flexor tendons were exposed. The distal stump of the FDP tendon was located proximal to the A1 pulley. The tear was found to be in Zone 3 (Fig. 1).

Figure 1: (a) Intraoperative identification of the distal end of the torn tendon. (b) Identification of the proximal retracted end of the tendon. (c) Post-repair condition.

Friable hemorrhagic tissue was noted at the stump site. The A1 pulley was released in a longitudinal fashion. The palmar incision was extended proximally to the proximal aspect of the carpal tunnel. A synovial biopsy was obtained from the carpal tunnel and later resulted a negative for inflammatory or infectious processes. The proximal stump of the FDP was located just proximal to the carpal tunnel. The FDP tendon was then repaired primarily using Arthrex FiberLoop (Naples, FL) suture in a four-strand cruciate fashion, reinforced by 4-0 nylon suture and 5-0 polydioxanone epitendinous locked circumferential suture (Fig. 1). The presence of the tenodesis effect and restoration of the digital flexion cascade were noted on examination intraoperatively. The incision was closed, and a dorsal clamdigger splint was applied.

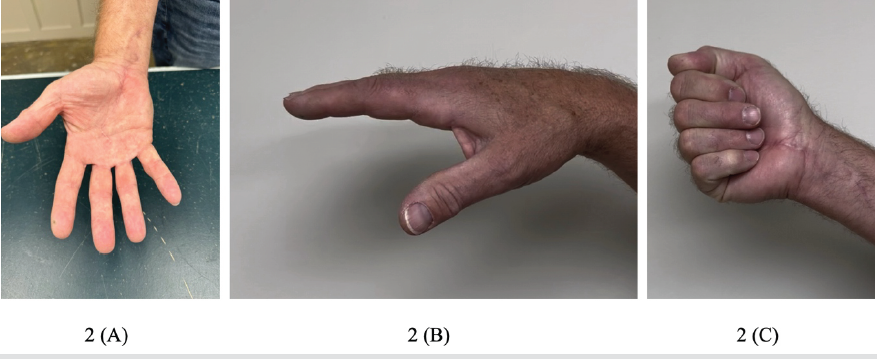

The patient was transitioned to a removable clamdigger splint at the first postoperative visit and occupational therapy with initiated on postoperative day 9 with the following protocol: Buddy strapping middle and ring fingers, initiation and general progression of active, active-assisted, and passive range of motion (ROM). Informed consent was taken from the patient for the scientific publication of his injury, ensuring adherence to ethical standards. 12 months postoperatively, the patient regained 5/5 FDP strength compared to the contralateral side, was at full extension and 5° short of full flexion at the DIP, and reported 95% subjective functional improvement. Fig. 2a, b, c shows the 15-month follow-up. The patient achieved a total active ROM of 230, which is considered a good outcome according to the TAM Scoring system.

Figure 2: (a and b) Illustrating the full extension, while (c) demonstrates the hand forming a fist, 15 months’ follow-up.

Ruptures of the flexor tendon within Zone 3 are infrequent yet complex clinical entities that pose diagnostic and therapeutic challenges. The variability in clinical presentations and therapeutic approaches has led to a scarcity of consensus within the literature regarding the management of these injuries. We present a rare case of middle finger zone 3 FDP rupture without an identifiable underlying cause. In addition, this paper synthesizes a detailed examination of current literature focused on Zone 3 flexor tendon injuries, aiming to elucidate treatment modalities and recommendations based on the most recent evidence. The findings from this evaluation are discussed in the subsequent sections. We have attached supplemental files containing the data from all the studies we have reviewed.

Literature search strategy

A systematic literature search was conducted utilizing the PubMed, Scopus, and Google Scholar databases. Keywords and Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) terms included “Zone 3,” “Flexor Digitorum Profundus (FDP),” “Flexor Digitorum Superficialis (FDS),” and “Injury” or “Rupture,” combined using Boolean logic “AND.” Our initial search yielded 349 articles. Studies published in languages other than English, review articles, instructional course lectures, and purely technique-focused articles were excluded. Inclusion criteria were limited to original, patient-focused research specifically addressing Zone 3 flexor tendon injuries. Ultimately, 66 articles meeting the defined criteria, case reports and case series specifically describing Zone 3 flexor tendon injuries, were included for analysis. Studies reporting injuries in zones other than Zone 3 were excluded to maintain specificity and relevance.

Demographics

In this comprehensive review, we assimilated data from 27 studies [10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36], encompassing a total of 66 patients, with the range of literature extending from 1960 to 2025 (Table 1 from Supplementary File).

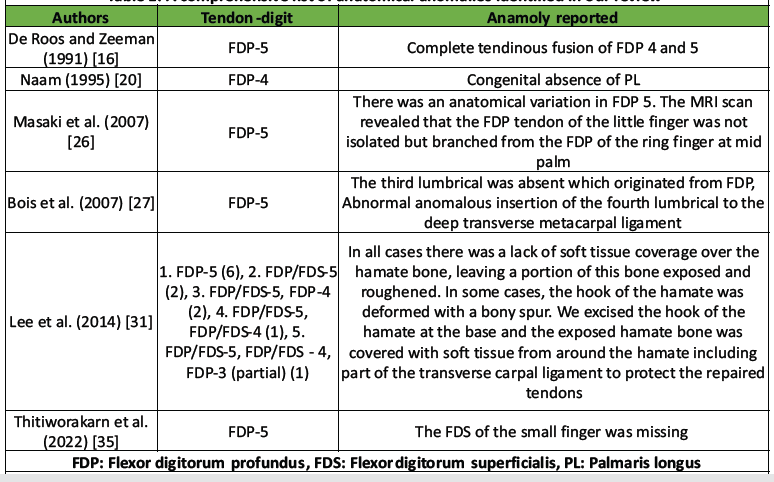

Table 1: A comprehensive list of anatomical anomalies identified in our review

The average age was 52.52 years, with the youngest at 16 years and the eldest at 79 years. We included 17 single case reports, while 10 studies reported on multiple patients. Of these, three studies reported on 2 cases each, two studies on 3 cases each, two studies on 4 cases each, one study on 5 cases, and, notably, two studies reported on 12 cases each. The male-to-female ratio of approximately 3.7:1, with 52 males and 14 females. Occupational details were not disclosed in 17 cases. Notable occupational details include a professional tennis player, as documented by Hang et al. [23], and a group of Korean farmers, comprising all 12 cases in the study by Lee et al. [31]. The review showed a higher incidence of right-sided cases at 42, versus 24 left-sided, yielding a right-to-left ratio of 1.75:1. When considering limb dominance, 40 cases involved the dominant side, while 16 were on the non-dominant side. Data on limb dominance were missing for 10 cases.

Clinical presentations

The most frequent clinical symptom is a sensation of a snap or pop in the palm, often followed by immediate sharp pain. This is a recurrent presentation, reported in various forms such as “snap was felt at the palm,” “small snap followed by pain,” and similar descriptions. Pain, either sharp or dull, occurs suddenly and is sometimes associated with specific activities, such as lifting heavy objects. Descriptions reported by various authors are “sudden onset of pain,” “excruciating pain at the time of injury,” and “sharp pain.” In many cases, this is accompanied by functional impairment, specifically an inability to flex one or more fingers. This symptom is described plainly as “inability to flex the finger” or in more detail, mentioning specific joints like the “distal interphalangeal joint (DIPJ).” Swelling and palpable masses are also noted in some cases. While three patients reported no symptoms at all (Asymptomatic), and five patients had no data reported by the authors.

In our review, the timeframe from injury to clinical presentation varied widely. While five cases did not report the interval, two patients sought immediate medical attention. Among those that specified the duration, the maximum time to presentation was approximately 24 months (730 days), with the minimum being as short as 2 days. On average, patients presented at 40.89 days post-injury. However, this average is influenced by a substantial standard deviation of 118.08 days, indicating varied patient response times to seeking care.

Mechanism of the injury

After reviewing the mechanisms of injury for Zone 3 flexor tendon injuries, the analysis reveals:

- “Resisted flexion” is the most frequently reported mechanism, indicating that injuries often occurred during activities where the fingers were actively flexing against a resistance.

- “Sudden hyperextension” is another common mechanism, where the injury is caused by a rapid and forceful extension of the finger, often beyond its normal ROM. This could be a result of an external force or an abrupt movement by the patient. “Hyperextension” and variations such as “Forced Hyperextension at the level of Metacarpophalangeal joint (MCP)” or

- “Hyperextension of flexed finger” is also noted, pointing to a similar but slightly different pattern of injury compared to sudden hyperextension.

- Traumatic causes such as “Blunt Trauma to the palm” and “Jersey finger” mechanism, the latter typically occurring in sports like rugby, are also listed, though they appear less frequently. “Longitudinal Force” and activities involving “repetitive wrist motion combined with power grip” are described, highlighting occupational and sports-related risk factors.

- Notably, a single case mentions “The patient is on immunosuppression with a history of renal transplant,” suggesting a possible systemic factor contributing to tendon vulnerability. There are three cases categorized as “Atraumatic” by Bois et al. [27]. Four cases lack detailed reports on the mechanism of injury by the authors.

In summary, the dominant mechanism of injury is resisted flexion, followed by various forms of hyperextension in our review. Atraumatic cases and specific situational factors, such as occupational hazards and sports injuries, are also noted but are less common.

The concept of “spontaneous rupture,” of the FDP, defined as tendon rupture without overt pathology or preceding trauma, has been reported in the literature. Lee et al. [37] critically examined this and found that 36 reported cases of FDP ruptures in the little finger were reported “spontaneous,” only one case genuinely lacked associated trauma or discernible pathological condition. The remaining cases were associated with anatomical variations or other predisposing factors. Table 1 summarizes all anatomical anomalies identified in our review of Zone 3 flexor tendon injuries.

Similarly, our analysis with only a single case from Bois et al. [27] characterized it as “spontaneous” in the absence of trauma history. However, the predominant mechanism identified in the literature and within our case report is acute trauma, which suggests that true spontaneous ruptures are exceedingly rare.

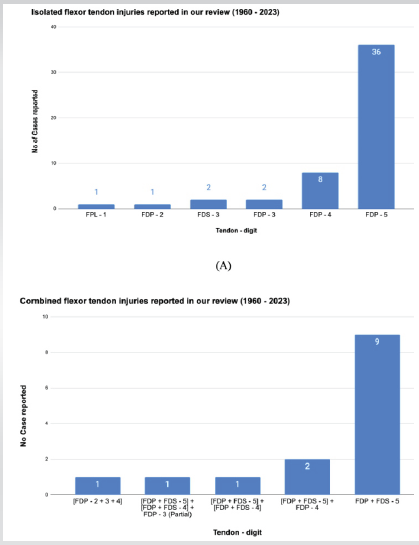

Flexor tendon injury distributions in Zone 3

Flexor tendon injuries in Zone 3 can be classified as either isolated, affecting a single tendon, or complex, involving multiple tendons. Isolated injuries are more prevalent than combined ones. Fig. 3a presents the distribution of flexor tendon injuries reported in Zone 3 as per our review. The data indicate that the FDP of the fifth digit is the most commonly affected tendon in isolation, as well as overall within Zone 3. Specifically, 36 out of 66 involved an isolated rupture of the FDP of the fifth digit, followed by eight isolated injuries of the FDP of the fourth digit, two of the third digit, and one isolated case each for the FDP of the second digit and the flexor pollicis longus (FPL) of the first digit. Only two cases were reported with isolated FDS injuries.

Figure 3: Vertical Bar graph (a) represents the number of isolated flexor tendon injuries reported and (b) represents the number of combined flexor tendon injuries reported.

Regarding combined flexor tendon injuries, the most prevalent involved the FDS and FDP of the fifth digit, with nine cases documented as presented by (Fig. 3b). Lee et al. [31] reported a case series of 12 Korean farmers, two of whom sustained combined injuries of the FDS and FDP of the fifth finger, with concurrent involvement of the FDP of the fourth digit. In addition, there was one case each of combined FDS and FDP injuries of the fifth and fourth digits, and a case involving the FDS and FDP of the fourth and fifth digits with a partial injury to the FDP of the third finger. Injuries involving the FDP of the second, third, and fourth digits in a single case were also reported, although such occurrences are rare.

Anatomical retraction patterns, histological findings

Understanding the extent of tendon retraction in Zone 2 flexor tendon injuries is crucial for surgical planning and prognostication. Our review indicates the location of the retracted tendon end in relation to the lumbrical muscle origins. Specifically, the proximal end of the retracted tendon was found to be at the origin of the lumbrical muscles in 18 cases, distal to the lumbricals in 14 cases, and proximal to the lumbricals in 5 cases. In 29 cases, the data regarding the position of the tendon retraction in relation to the lumbricals were not available.

Histological examination of the tissues, a valuable tool for assessing the integrity and quality of the tendons, was reported as normal in 23 cases. In 21 instances, histological assessments were not performed, which leaves a gap in the comprehensive understanding of the tendon condition. Furthermore, 12 cases lacked applicable histological data.

Pre-operative imaging and Carpal tunnel exploration

Our review noted that 14 cases lacked reported diagnostic methods. Radiography was performed on 32 cases to rule out carpal bone abnormality or fractures, while Coomb and Mutimer [17] used ultrasonography (USG) on two patients for tendon location. Lee et al. [31] used both USG and X-ray for a group of 12 Korean farmers. Yoon et al. [34] employed both USG and Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) preoperatively. MRI was also used by Drape et al. [22] (three patients), Kumar and James [12] (one patient), and Li et al. [30] (one patient) for tendon injury assessment.

We also review the description of the incision described by the authors. Among authors who described their incision in detail, 46% (31 out of 66) commented that carpal tunnel exploration was required to locate and retrieve the proximal tendon stump. Conversely, the carpal tunnel was not explored in 4 cases, and in another 31 cases, data were not available, indicating an area where reporting could be enhanced.

Management and outcome of the tendon injuries in Zone 3

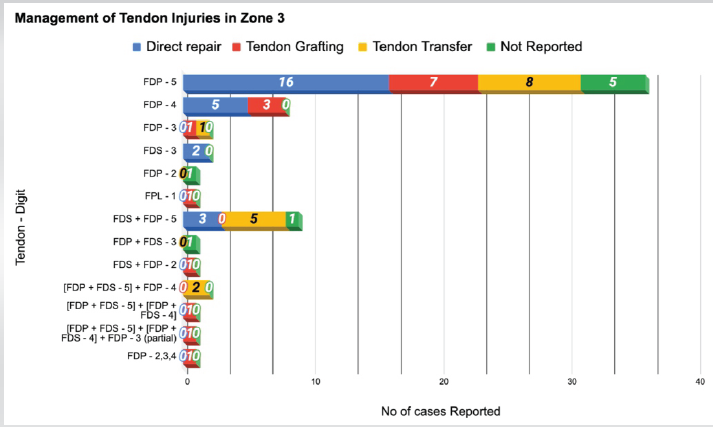

Figure 4: Horizontal bar graph depicting the management strategies described for each tendon injury.

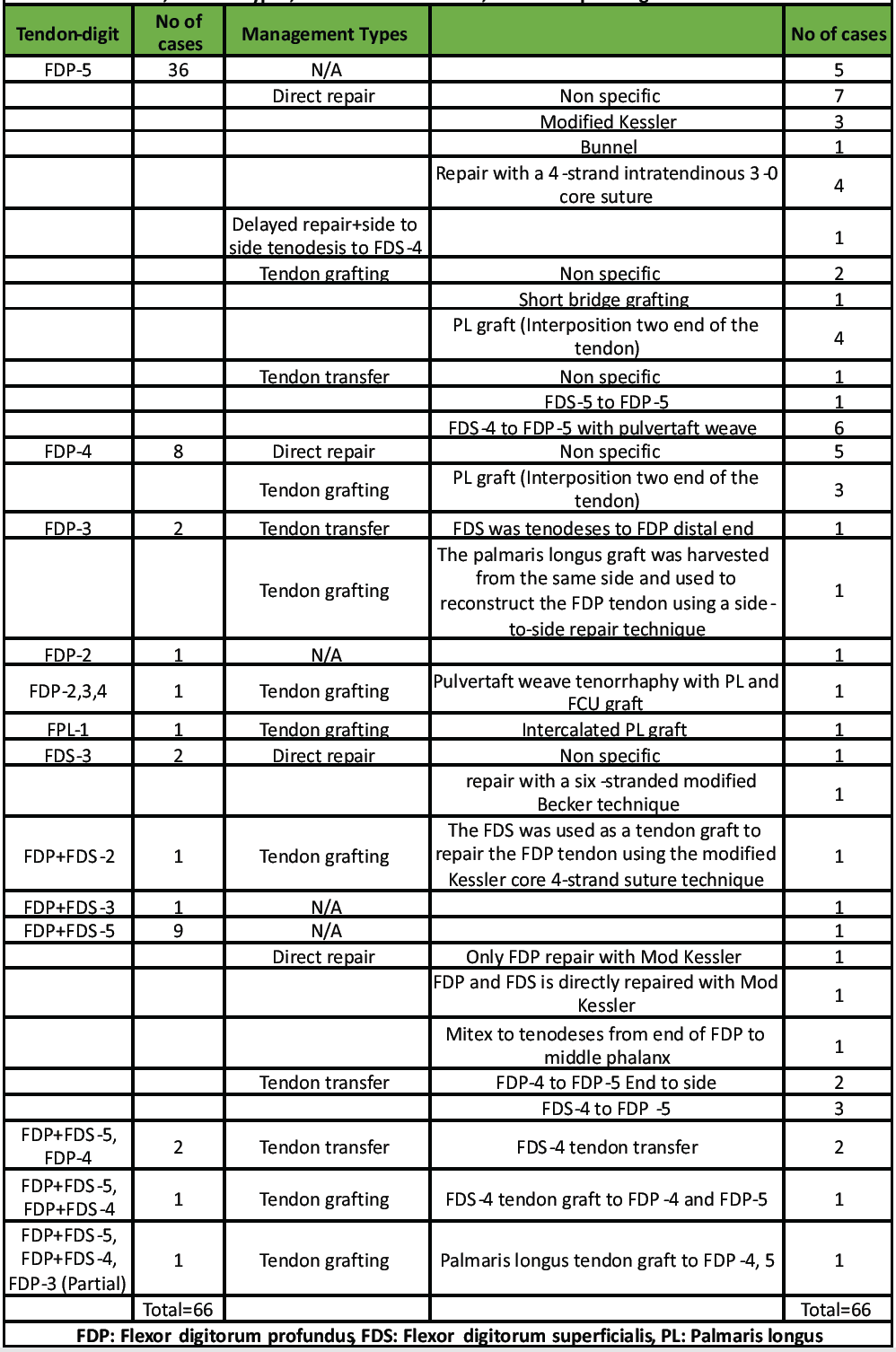

Fig. 4 shows the different management options that have been reported according to the tendon. The most common method of management is the direct repair, for which various types of repair have been reported (Refer to Table 2 from supplementary file).

Table 2: Various tendon transfer techniques used in Zone 3 flexor tendon injuries, detailing the injured tendons, transfer types, donor tendon deficits, and corresponding clinical outcomes

Modified Kessler, Bunnel, 4-core stranded suture techniques, and Pulvertaft weave technique have been reported. Many case of direct repair was specified as “Non-specific” by the author. Twenty-three out of 66 cases of various tendon injury have been reported to be managed by direct repair. All the cases of the “Direct repair” reported excellent outcomes, except one case reported by Davis and Armstrong [24], which was managed by the intratendinous 3-0 core suture and 5-0 nylon epitendinous suture. This patient was not compliant with the post-operative physical therapy and eventually lost to follow-up, as per the author. All cases managed by direct repair have shown excellent outcomes with no residual deformity.

Tendon grafting has been reported in 18 cases each in our review. For Tendon grafting, the most commonly used graft is palmaris longus (PL) (10 out of 16). One case report used the PL with the Flexor carpi Ulnaris (FCU) graft. Ostric et al. [29] reported case of the FDP tendon injury of 2nd, 3rd and 4th digit which was managed by Pulverate weave technique with PL and FCU graft, This case has a moderately good outcome reported with full flexion at MCP, PIP but lacked the full DIP flexion at closed fist, and at 18 months his finger grip was 50% of the opposite side. In 3 cases, the author reported “ruptured FDS of same or nearby digit” or “the intact FDS of the nearby normal digit” also used as the graft to repair the FDP. It seems like the continuation of the FDP is more important than the FDS for the normal function of the hand and digit. Three cases were reported that underwent non-specific “Tendon transfer” by the author. All the reported tendon transfers were performed in a single-stage procedure as a primary reconstruction.

The outcome of the Tendon grafting is not as good as direct repair. Three cases that has been managed with PL tendon grafting, reported the poor outcome, one case was FPL tendon the thumb, which ended up having TAM of 62°, another case was reported by Lee et al. [31] had a FDP and FDS of the 4th and 5th finger was injured, which was managed by PL grafting for FDP of the both digit. TAM for the 4th digit was reported to be 120. Another case reported by Zahid et al. [33] of FDP of the 3rd digit was ruptured, ended up having stiffness in the adjacent digits.

Figure 5: Illustrations of tendon transfer techniques summarized in Table 2. Each sub-figure shows specific tendon transfers: (6.1) FDS-5 to FDP-5, (6.2) FDS-4 to FDP-5, (6.3) end-to-side FDP-4 to FDP-5, (6.4) FDS-3 to FDP-3, (6.5) FDS-4 to FDP-4 and FDP-5, and (6.6) FDP-3 to FDP-4 and FDP-5.

For Tendon transfer, 16 cases were reported to be managed by it. Table 2 and Fig. 5 collectively illustrate the various tendon transfer techniques used in Zone 3 flexor tendon injuries, detailing the injured tendons, transfer types, donor tendon deficits, and corresponding clinical outcomes.

The reporting on the management of flexor tendon injuries lacked uniformity, with considerable variations in the methods of documentation. The total active motion (TAM) scale [38] is a widely recognized method for quantifying hand surgery outcomes, categorizing them as <130 for “poor”, 130–194 for “fair,” 195–259 for “good,” and over 260 for “excellent.” In an analysis of 66 case reports, 7 did not report any management strategy, and 8 failed to mention outcomes, merely describing the management techniques used. Of the 51 reports that did document outcomes, 13 utilized vague, non-specific terms such as “full recovery” or “normal range.” Only 11 reports provided actual objective ROM data. The TAM, which is the most objective measure, was used by only two authors, Naam [20] and Lee et al. [31], each presented a case series involving 12 patients. McLain and Steyers [19], who discussed a case series involving three patients with Zone 3 injuries, objectively reported the outcomes for two patients using TAM.

Given the observed inconsistencies in current literature reporting, we propose the following minimum dataset for standardized documentation of Zone 3 flexor tendon injuries

- Baseline demographics:

- Age

- Gender

- Dominant hand

- Occupation or relevant physical activity

- Injury characteristics

- Mechanism of injury (e.g., resisted flexion, sudden hyperextension, blunt trauma, atraumatic)

- Specific tendon(s) involved

- Time elapsed from injury to diagnosis

- Clinical findings and imaging

- Clinical symptoms (e.g., “pop” sensation, inability to flex joints, swelling)

- Physical examination findings (e.g., tenodesis effect, tenderness location)

- Imaging modalities used for diagnosis (e.g., X-ray, Ultrasound, MRI)

- Surgical details

- Surgical approach and incisions

- Surgical technique used (e.g., direct repair, tendon grafting, tendon transfer)

- Specific suture techniques and materials

- Extent of tendon retraction and anatomical reference points (e.g., lumbrical muscle origin)

- Intraoperative findings, including tissue quality and any associated anomalies

- Postoperative rehabilitation protocol

- Type and duration of immobilization (e.g., splint type, duration)

- Timeline for initiating active and passive range-of-motion exercises

- Details of occupational therapy protocol

- Outcome reporting

- Functional outcome measured by TAM score

- Strength comparison to the contralateral side

- Patient-reported subjective recovery percentage

- Complications or additional procedures, if any

Establishing this minimum dataset will facilitate better comparative analyses, improve clinical understanding, and enhance patient outcomes in Zone 3 flexor tendon injuries.

Our case of isolated FDP injury in Zone 3 of the middle finger is unique, as there were only two cases reported between 1960 and 2025. One was reported by Walker and Lesavoy [15], which was managed by tendon transfer, 7 weeks post-injury, with the distal part of the FDP tenodesed to the FDS of the same finger. Another one was reported by Zahid et al. [33], which was managed with a PL autograft and side-to-side repair, 2 weeks post-injury. We managed our case with direct repair, 4 days post-injury.

Notably, both Zahid et al. [33] and our case shared the challenge of initial misdiagnosis as a Zone 1 injury, likely Leddy-Packer Type I, leading to initial distal exploration. This highlights a key learning point: While clinical examination remains paramount, the use of bedside ultrasonography should be considered to localize the proximal tendon stump and more accurately determine the zone of injury before surgery. Incorporating preoperative imaging when feasible may avoid unnecessary distal incisions and improve surgical planning. Even if the diagnosis had been established preoperatively using imaging modalities, the rarity of an isolated Zone 3 FDP rupture in the middle finger provides significant novelty and clinical value to the literature. Our findings of the literature review of Zone 3 flexor tendon injuries can be summarized as follows:

- Men are 3.7 times more likely to have Zone 3 injuries, predominantly affecting the right dominant hand.

- The FDP of the fifth digit is the most common tendon injured in Zone 3. Injuries to other tendons and combined tendon injuries occur but are less common.

- Zone 3 injuries are most commonly a result of resisted flexion or sudden hyperextension. Blunt trauma or repetitive wrist motion are less common causes.

- Clinical symptoms typically begin with a snapping sensation in the palm, leading to sharp pain and often resulting in functional impairment, particularly the inability to flex the fingers. Symptom severity and functional impact vary, with some patients being asymptomatic.

- X-ray is the most commonly reported imaging technique to exclude bone abnormalities. USG and MRI should be used for precise localization and assessment of tendon injuries, particularly when injuries are suspected outside of Zones 1 and 2. MRI can also locate anatomical anomalies such as tendinous fusion and variations in lumbrical muscles, which may predispose to injury.

- The predominant treatment method reported is direct repair, with tendon grafting and transfers also reported, though these methods yield less favorable outcomes compared to direct repair. All grafting and tendon transfer procedures were conducted as single-stage primary reconstructions. The use of the TAM scale for outcome reporting is recommended but not consistently applied.

- Tendon transfer procedures typically utilize the FDS of an adjacent, non-injured digit, or from the same injured digit, to repair the FDP. Despite this sacrifice, functional outcomes do not significantly differ.

This case highlights the challenges posed by isolated Zone 3 FDP injuries in the middle finger, especially when they mimic more common Zone 1 avulsions. A thorough clinical examination remains the cornerstone of diagnosis. However, in the presence of diffuse tenderness or equivocal findings, bedside ultrasonography can serve as a valuable adjunct to improve preoperative localization. We propose a minimum dataset for future reporting of Zone 3 injuries to facilitate standardized documentation and encourage broader recognition of this rare entity. Early recognition and appropriate surgical planning are essential for optimizing functional outcomes in these uncommon injuries.

Loss of DIP flexion with an intact distal insertion should trigger suspicion for a hidden Zone 3 FDP rupture; early imaging and prompt primary repair can restore full function.

References

- 1. Netscher DT, Badal JJ. Closed flexor tendon ruptures. J. Hand Surg 2014;39:2315-23. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 2. Ertel AN. Flexor tendon ruptures in rheumatoid arthritis. Hand Clin 1989;5:177-90. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 3. Jebson PJ, Ferlic RJ, Engber WF. Spontaneous rupture of ulnar-sided digital flexor tendons: Don’t forget the hamate. Iowa Orthop J 1995;15:225-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 4. Masada K, Kanazawa M, Fuji T. Flexor tendon ruptures caused by an intraosseous ganglion of the hook of the hamate. J Hand Surg Edinb Scotl 1997;22:383-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 5. Roberts JO, Regan PJ, Roberts AH. Rupture of flexor pollicis longus as a complication of Colles’ fracture: A case report. J Hand Surg Br 1990;15:370-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 6. Anzel SH, Covey KW, Weiner AD, Lipscomb PR. Disruption of muscles and tendons; an analysis of 1, 014 cases. Surgery 1959;45:406-14. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 7. Fitzgerald BT, Hofmeister EP, Fan RA, Thompson MA. Delayed flexor digitorum superficialis and profundus ruptures in a trigger finger after a steroid injection: A case report. J Hand Surg 2005;30:479-82. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 8. Lundborg G, Myrhage R, Rydevik B. The vascularization of human flexor tendons within the digital synovial sheath region–structureal and functional aspects. J Hand Surg 1977;2:417-27. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 9. Kannus P, Józsa L. Histopathological changes preceding spontaneous rupture of a tendon. A controlled study of 891 patients. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1991;73:1507-25. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 10. Boyes JH, Wilson JN, Smith JW. Flexor-tendon ruptures in the forearm and hand. J Bone Jt Surg 1960;42-A:637-46. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 11. Bickley RJ, Deal JB, Frazier RL, Daner WE. Closed rupture of flexor digitorum profundus in zone III. BMJ Case Rep 2020;13:e234393. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 12. Kumar S, James R. Closed rupture of flexor profundus tendon in the palm. J Hand Surg Br 1985;10:193-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 13. Imbriglia JE, Goldstein SA. Intratendinous ruptures of the flexor digitorum profundus tendon of the small finger. J Hand Surg Am 1987;12:985-91. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 14. Wray RC Jr., Parlin LS. Spontaneous flexor tendon rupture in the palm. Ann Plast Surg 1989;23:352-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 15. Walker LG, Lesavoy MA. Traumatic rupture of the profundus tendon proximal to the lumbrical origin. J Hand Surg 1990;15:484-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 16. De Roos WK, Zeeman RJ. A flexor tendon rupture in the palm of the hand. J Hand Surg Am 1991;16:663-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 17. Coombs CJ, Mutimer KL. Closed flexor tendon rupture in the palm: An unusual but predictable clinical entity. Aust N Z J Surg 1993;63:910-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 18. Takami H, Takahashi S, Ando M. Rupture of the flexor digitorum profundus tendon in the palm caused by repeated, chronic direct trauma. J Hand Surg 1993;18:65-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 19. McLain RF, Steyers C, Blair W. Spontaneous rupture of digital flexor tendons. Orthopedics 1994;17;292-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 20. Naam NH. Intratendinous rupture of the flexor digitorum profundus tendon in zones II and III. J Hand Surg Am 1995;20:478-83. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 21. Yang SS, McCormack RR, Weiland AJ. Closed rupture of the flexor digitorum profundus tendon in the palm of a non-rheumatoid patient. Orthopedics 1998;21:205-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 22. Drapé JL, Tardif-Chastenet De Gery S, Silbermann-Hoffman O, Chevrot A, Houvet P, Alnot JY, et al. Closed ruptures of the flexor digitorum tendons: MRI evaluation. Skeletal Radiol 1998;27:617-24. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 23. Hang YS, Hang DW, Liu TK, Hou SM. Rupture of the flexor digitorum profundus tendon of the small finger. Am J Sports Med 2002;30:903-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 24. Davis C, Armstrong J. Spontaneous flexor tendon rupture in the palm: The role of a variation of tendon anatomy. J Hand Surg Am 2003;28:149-52. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 25. Krishnamurthy A, Golla D, Lee WA, Rubin JP. Traumatic intratendinous flexor digitorum profundus rupture: A case report. Can J Plast Surg 2005;13:151-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 26. Masaki F, Isao T, Aya Y, Ryuuji I, Yohjiroh M. Spontaneous flexor tendon rupture of the flexor digitorum profundus secondary to an anatomic variant. J Hand Surg Am 2007;32:1195-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 27. Bois AJ, Johnston G, Classen D. Spontaneous flexor tendon ruptures of the hand: Case series and review of the literature. J Hand Surg Am 2007;32:1061-71. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 28. Lin CJ, Lin MJ, Tsai CH. Simultaneous spontaneous ruptures of both flexor tendons in the little finger. J Hand Surg Eur Vol 2010;35:236. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 29. Ostric SA, Russell RC, Petrungaro J. Closed Zone III rupture of the flexor digitorum profundus tendons of the right index, long, and ring fingers in a bowler: Gutterball syndrome. Hand (N Y) 2010;5:378-81. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 30. Li WY, Rommer E, Kulber DA. Bilateral spontaneous flexor digitorum profundus tendon rupture of the fifth digit: Case report and literature review. Hand (N Y) 2013;8:239-41. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 31. Lee GJ, Kwak S, Kim HK, Ha SH, Lee HJ, Baek GH. Spontaneous Zone III rupture of the flexor tendons of the ulnar three digits in elderly Korean farmers. J Hand Surg Eur Vol 2015;40:281-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 32. Melamed E, Fineberg SJ, Beldner S. Closed rupture of the flexor profundus tendon of ring finger: Case report and treatment recommendations. Am. J. Orthop (Belle Mead NJ) 2015;44:373-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 33. Zahid R, Qazi U, Farner S. Spontaneous midsubstance rupture of the flexor digitorum profundus tendon of the long finger. J Hand Surg Glob Online 2022;4:306-10. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 34. Yoon JH, Jung JS, Kim H. Spontaneous zone III flexor tendon rupture of the little finger: A case report. J Wound Manag Res 2022;18:53-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 35. Thitiworakarn N, Vinitpairot C, Jianmongkol S. Closed spontaneous rupture of the flexor tendon in zone 3: A case series. J Southeast Asian Orthop 2022;46:39-43. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 36. Bouziane W, Missaoui Z. A rare case of an isolated neglected subcutaneous rupture of the flexor digitorum Superficialis in a climber: Successful surgical treatment and review of the literature. Cureus 2023;15:e36055. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 37. Lee JS, McGrouther DA. Are flexor tendon ruptures ever spontaneous? – a literature review on closed flexor tendon ruptures of the little finger. J Hand Surg Asian Pac Vol 2019;24:180-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 38. Magnani PE, Ferreira AM, Rodrigues EK, Barbosa RI, Mazzer N, Elui VM, et al. Is there a correlation between patient-reported outcome assessed by the disabilities of the arm, shoulder and hand questionnaire and total active motion after flexor tendon repair? Hand Ther 2012;17:37-41. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]