Traumatic posterior shoulder dislocation can rarely present with an isolated anterior leading edge tear of the subscapularis, a pathology with very few cases documented in the literature. This case highlights the importance of a thorough clinical examination along with diagnostic arthroscopy when identifying this particular pathology. Early recognition and surgical intervention can lead to excellent outcomes and recovery of function.

Dr. Frank McCormick, Department of Orthopedics Surgery, Musculoskeletal Institute of Bayonne University Hospital, 29 E 29th St, Bayonne - 07002, New Jersey, United States. E-mail: drfrankmccormick@yahoo.com

Introduction: A patient presented with traumatic posterior shoulder dislocation and underwent a diagnostic arthroscopy, where an acute subscapularis anterior leading edge tear was identified. This tear patient is exceptionally uncommon, having only been cited in the literature 5 times as of 2013, and to our knowledge, has no known documented cases since. This report seeks to summarize challenges associated with such a rare diagnosis by presenting a case where this rare presentation was timely diagnosed and treated with an optimal outcome, and to highlight pertinent details of the case that are critical to not miss this diagnosis in the future.

Case Report: This patient is a 45-year-old male who suffered a motor vehicle-pedestrian collision and was diagnosed with left posterior shoulder dislocation resulting in shoulder instability. Physical exam demonstrated signs of both shoulder instability as well as cervical radiculopathy. No other workup or history-taking yielded significant results, other than a distant past medical history of acute neurological distress from traumatic brain injury. The treatment plan consisted of diagnostic arthroscopy with the expectation of finding associated soft tissue and labral pathology and possible Bankart and other indicated soft tissue repair for instability. Upon arthroscopic investigation, not only was a posterior labral tear identified, but also an unexpected anterior edge subscapularis tear. The patient demonstrated rapid pain relief in the immediate post-operative period.

Conclusion: Acute posterior shoulder dislocations of the shoulder are seldomly reported in the literature, with even fewer cases reporting on associated rotator cuff tears with this injury. Due to the challenges associated with diagnosing subscapularis tears following posterior shoulder dislocation, we encourage standardization of the variable terminology of subscapularis tear classifications and for surgeons to be aware of the potential of subscapularis pathology with frontal impact injuries. With the increase of motor vehicle accidents, we postulate that this rare scapularis tear patten may become more prevalent and requiring an expanding body of literature on the topic.

Keywords: Posterior shoulder dislocation, posterior shoulder instability, subscapularis, anterior leading edge tear, shoulder arthroscopy, and rotator cuff tear.

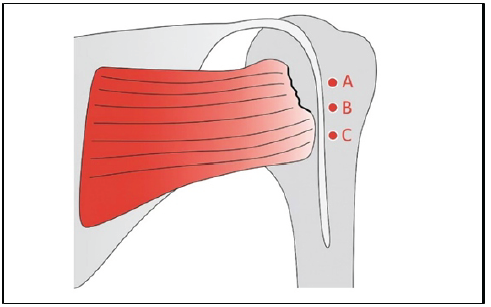

Posterior shoulder dislocation is a rare clinical indication that only accounts for a small percentage of 2–5% of all combined shoulder dislocations [1]. Recent literature places this percentage at close to 3% [2]. For posterior dislocations and resultant posterior shoulder instability, with their relative rarity, an emphasis is placed on diagnostic criteria. Despite the presence of well-described clinical presentations, the rate of misdiagnosing posterior shoulder dislocations remains high, with recent systematic literature reporting approximately 50–79% of cases missed on initial evaluation [2]. Diagnosing posterior shoulder dislocations starts with the initial observation of the patient. A common sign for patients is holding their arm flexed, adducted, and internally rotated [3]. Further examinations can reveal a prominent coracoid process, leveling of the anterior deltoid, and a characteristic skin dimple inferior and medial to the posterolateral edge of the acromion [4]. However, the lack of standardized diagnostic clinical criteria necessitates diagnosis through radiographic imaging, often including anteroposterior (AP), scapular lateral, and axillary views [5]. Even in cases where the AP view appears seemingly indeterminate, identifying the characteristic lightbulb sign [6] can confirm the diagnosis. Furthermore, the diagnosis of dislocation-associated rotator cuff and labral injuries present additional challenges. Isolated subscapularis tears are another rare should pathology, consisting of only 4% of all rotator cuff tears [7]. One particular tear pattern, anterior leading edge tears of the subscapularis, are characterized by peeling off the distal insertion of the subscapularis from the humoral head, as shown in Fig. 1.

Figure 1: Graphic showing a Type I anterior leading edge tear of the subscapularis. Point A on the superior fibers shows the location of the described tear in this case.

The mechanism of injury for these tears is often a violent, sudden external rotation of the shoulder with abduction, or forced extension of the shoulder [8]. We seek to expand the knowledge on the topic of the provided etiology of posteromedial compressive forces as being correlated with both posterior shoulder dislocation and subscapularis tears.

Although shoulder injuries are well described in the literature, Liaghat et al. state that there is a lack of common terminology used when discussing the modality of onset of shoulder injuries [9]. Tying these two rare indications together in the clinical setting highlights a rare correlation of injuries, which while uncommon, providers should be aware of to treat promptly and appropriately.

Patient presentation

A 45-year-old man presented with left shoulder pain starting immediately following a motor vehicle-pedestrian collision, where he was struck by a truck while riding his motorized bicycle.

He presented to the orthopedic surgeon for left shoulder pain in the clinic 2 months following the injury, having failed attempts of conservative management. He had consulted a physical medicine and rehabilitation physician for his shoulder pain prior, also investigating concomitant back and neck pain, but was referred to an orthopedic surgeon for his shoulder pain along with a recommendation to get a shoulder magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). The MRI revealed that the patient had suffered a tear in the superior, posterior labrum, a 1 cm cyst in the humerus, along with a partial thickness tear of the subscapularis consistent with a Type I anterior leading edge tear on the Yoo and Rhee classification scale [8]. Physical examination in the orthopedic clinic revealed posterior shoulder instability consistent with a labral tear with a positive O’Brien’s test, along with range of motion limited by pain, and dyskinesis of the shoulder without atrophy or scarring. Tenderness of the anterior shoulder was noted, but non-tender to palpation at the lateral and posterior aspects of the shoulder, acromioclavicular joint, or biceps groove. Provocative testing was done with the Neer, Hawkins, cross-arm, uppercut, and Speed’s test all negative. Following the examination, the patient was recommended left shoulder arthroscopy with labral repair, and the associated risks and recovery process were also discussed with the patient. Pre-operative diagnosis was left shoulder rotator cuff tear, left shoulder impingement, left shoulder biceps tendinitis, and left shoulder posterior labral tear.

Surgical intervention

After diagnosis, the patient chose to undergo the indicated surgery of left shoulder arthroscopy, rotator cuff repair versus debridement, subacromial decompression, labral repair versus debridement, and anticipated biceps tenodesis. Two months later, the surgery took place at an outpatient surgery center.

After consent was reviewed in the pre-operative hold, the operative site was confirmed with the “sign your sign” protocol. The patient was taken to the OR and placed in a beach chair position with care taken to pad all bony prominences. Time out was performed with all agreeing to correct the site, patient, and procedure. Antibiotics were confirmed as well by the surgeon and the rest of the team. Anterior and posterior shoulder working portals were used for the initial debridement with a rotary shaver, along with electro frequency ablation in the anterior interval, rotator cuff, and Superior labral anterior to posterior. Next, the surgeon performed a biceps tenotomy at the biceps labral junction after noting inflammation of the proximal long head of the biceps. Next, the surgeon performed a capsular release at the anterior interval, supraglenoid, and from coracoid to subscapularis. The surgeon then used a separate lateral portal to gain access to the subacromial space for debridement of the significant bursal inflammation. The supraspinatus was noted as being intact with continuous external and internal rotation. The rotating burr was used with a cutting block technique to make a smooth area, and at completion of the subacromial decompression, there was ample bursal debridement and subacromial space.

The surgeon then turned his attention to the posterior labral tear. Starting with a debridement of the posterior labrum, he then inserted a cannula into the posterior superior aspects of the shoulder, where he placed two suture anchors at 6 o’clock and 7 o’clock. Afterward, the surgeon reapproximated the inferoposterior bankart labrum along with the inferior glenohumeral ligament, middle glenohumeral ligament and posterior capsule to restore proper posterior restraint of the shoulder. The humoral head was well centered, and we had a loss of the drive-through sign following approximation.

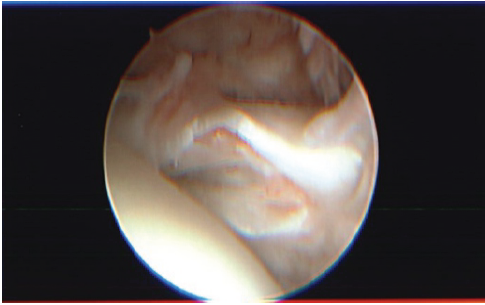

Finally, attention was made to the rotator cuff. There was an identified anterior leading edge tear to the subscapularis, shown in Fig. 2.

Figure 2: Arthroscopic visualization of the subscapularis with a Type I anterior leading edge tear, showing longitudinal splitting of the anterior edge with fraying of the tissue.

The repair began by using a biologic augmentation approach with decortication to allow for a bleeding bone bed. Next, a fiber tape Mason-Allen type stitch was configured from the anterior to the posterior edge of the tear. Then a lateral row suture anchor was used to pass the sutures through, followed by the placement of the suture anchor to the footprint natively. The suture was tensioned to provide a near-anatomic tension-free rotator cuff footprint repair. At completion, the rotator cuff moved in congruity with the movement of the humeral head.

The patient was discharged the same day as the surgery with a sling for comfort and multimodal pain medication. Activity was to be performed as tolerated with 28 days of no heavy lifting.

Post-operative

Post-operative visits were conducted at 2 weeks, 2 months, 6 months, and 1 year. At each post-operative appointment, the patient was noted for being ahead of schedule with no complications post-operatively. One-year post-operative evaluation was conducted by the surgeon with a reported American Shoulder and Elbow Surgeons score of 85 and quality of recovery described as excellent with regards to functional outcome, with no noted posterior shoulder instability. The results are consistent with Rouleau’s meta-analysis of acute posterior shoulder dislocations, showing only 18% of patients have residual instability following surgical intervention [6].

Rotator cuff tears are known to occur in association with traumatic anterior shoulder dislocation, especially in patients over 40 years of age; however, an association with a posterior dislocation is uncommon, regardless of the patient’s age [10]. According to the relevant literature, the most common complication after posterior shoulder dislocations is recurrent instability, which occurs at an early stage in 17.7% of shoulders within the 1st year of dislocation even in the absence of bony lesions, leading to substantial risk when not treated; the risk of posterior instability is highest in patients who are <40 years old [11,12].

Massive rotator cuff tears, defined as involving two or more tendons, in association with posterior shoulder dislocations, have been sparsely reported in the literature. Leunam et al. stated in a 2012 study that only four such cases had been documented [10]. Schoenfield et al. introduced early insight to the rarity of isolated rotator cuff tears, and their association with posterior shoulder dislocations, stating in a 2007 study that only 2 incidences of lone rotator cuff tears secondary to traumatic posterior shoulder dislocation had been described at the time [13]. This case report narrows the scope to isolated subscapularis tears without additional rotator cuff pathology, after identifying a noted gap in the literature.

Robinson et al. found that the prevalence of posterior dislocation was 1.1/100,000 population per year, with peaks in male patients between 20 and 49 years old, as well as in elderly patients over 70-years-old [12 ROBINSON]. Posterior dislocations can be categorized anatomically as subacromial, subglenoid, or subspinous based on where the humeral head ultimately rests; typically, the humeral head results posteriorly positioned relative to the glenoid and inferiorly in relation to the acromion [13]. The mechanisms responsible for posterior shoulder dislocations frequently involve forceful internal rotation, adduction, and shoulder flexion secondary to high-energy shoulder trauma such as motor vehicle accidents [14]. This injury may also be a result of violent muscle contractions produced by electrocution or seizures, and thus it is imperative for providers to consider a patient’s history to guide effective treatment [15,16].

Early recognition and treatment are imperative; a failure to appropriately diagnose and manage an acute posterior dislocation can lead to significant delays and complications such as development into chronic posterior dislocation, thus predisposing patients to degenerative changes in the shoulder joint [15,2]. Young patients in particular require prompt diagnosis based on the dire consequences of both long and short-term disabilities in the event that the tears fail to receive appropriate management [17].

Soon et al. describe the operative plan in a 2017 study showing the usage of an open technique to reduce the posterior shoulder dislocation, as well as using the same access to place two 4.5 mm anchors in both the subscapularis and the supraspinatus [18]. The surgical treatment for the previously mentioned case only utilized an open technique, while this case report details a more conservative approach to treating the subscapularis tear by way of arthroscopy. We believe that with proper diagnosis and effective clinical examination, it is possible to maintain a conservative approach to rotator cuff tears stemming from traumatic posterior shoulder dislocation.

Festbaum et al. stated that conservative treatment is a viable option for patients with only soft tissue or minor bony lesions after an acute posterior shoulder dislocation [19]. According to the available sources, patients with an atraumatic history of posterior shoulder instability tend to have more favorable outcomes with non-operative management compared to patients with a traumatic onset [20]. In cases of unsuccessful closed reduction, the reduction can be performed with the assistance of arthroscopy or by an open approach; available sources demonstrate that arthroscopy is an excellent tool to assist in reduction, diagnostic evaluation, and treatment [19]. Moreover, arthroscopically assisted reduction followed by arthroscopic posterior stabilization can allow the reduction of the dislocation without performing an open arthrotomy, consequently minimizing the overall morbidity of the patient [21]. Furthermore, an arthroscopic technique utilized for stabilization allows visualization of the entire glenohumeral joint and provides the surgeon the ability to directly address posterior disease as opposed to compensating for the defect with an anteriorly based transfer [17].

As previously discussed, there is scarce existing literature describing the association between posterior shoulder dislocations and rotator cuff tears. These rare comorbidities are commonly overlooked in young adults and thus must be considered when high-impact trauma to the shoulder is involved [21]. Upon examination, the relevant finding that should raise a provider’s index of suspicion for associated rotator cuff tears, is persistent severe pain following reduction of a dislocation; similarly, Goubier et al. suggest that the failure of abduction post-reduction should be considered as a potential indication for rotator cuff rupture [22].

With the increase of motor vehicle accidents in states such as Florida [23,24], we postulate that this indication could become more prevalent with the pressing need to expand the literature on the topic.

Surgical technique specificity in similar cases exists through the variance of resources, as well as surgeon expertise. This case was conducted as an elective surgery, with the necessary specific implants and tools available at the surgeon’s request. Similar cases where the subscapularis tear remains occult until diagnostic arthroscopy may not be able to utilize the described technique, which further emphasizes the need for thorough clinical evaluation before the operation. This study also contains other limitations, largely attributed to its nature as a single case report and an inability to generalize findings to a larger population.

Acute posterior dislocation of the shoulder by itself is rarely cited in the literature, with only 205 documented patients per a systematic review done in 2015. Rotator cuff tears associated with posterior dislocations only yielded 5 documented cases as of 2013, with subscapularis tears as the lone rotator cuff tendinopathy having no known mentions in the given period of time, to our knowledge. Although seldom literature exists regarding the stated case, this could be associated with a high frequency of misdiagnosis or missed entirely due to more readily apparent comorbidities. We encourage further research into traumatic posterior shoulder dislocations of the shoulder with associated lone subscapularis tears, as this association is of quite rarity, as evidenced by this case report.

Subscapularis tears secondary to traumatic posterior shoulder dislocation can often go unnoticed in polytrauma orthopedic cases, with sparse literature on the association between the two pathologies. This case report provides an example of the rare pathology along with the appropriate management leading to a successful outcome.

References

- 1. Paparoidamis G, Iliopoulos E, Narvani AA, Levy O, Tsiridis E, Polyzois I. Posterior shoulder fracture-dislocation: A systematic review of the literature and current aspects of management. Chin J Traumatol 2021;24:18-24. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 2. Kelly MJ, Holton AE, Cassar-Gheiti AJ, Hanna SA, Quinlan JF, Molony DC. The aetiology of posterior glenohumeral dislocations and occurrence of associated injuries: A systematic review. Bone Joint J 2019;101-B:15-21. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 3. Rowe CR, Zarins B. Chronic unreduced dislocations of the shoulder. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1982;64:494-505. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 4. Robinson CM, Aderinto J. Posterior shoulder dislocations and fracture-dislocations. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2005;87:639-50. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 5. Neer CS 2nd. Displaced proximal humeral fractures. I. Classification and evaluation. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1970;52:1077-89. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 6. Rouleau DM, Hebert-Davies J, Robinson CM. Acute traumatic posterior shoulder dislocation. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 2014;22:145-52. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 7. Deutsch A, Altchek DW, Veltri DM, Potter HG, Warren RF. Traumatic tears of the subscapularis tendon. Clinical diagnosis, magnetic resonance imaging findings, and operative treatment. Am J Sports Med 1997;25:13-22. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 8. Ghasemi SA, McCahon JA, Yoo JC, Toussaint B, McFarland EG, Bartolozzi AR, et al. Subscapularis tear classification implications regarding treatment and outcomes: Consensus decision-making. JSES Rev Rep Tech 2023;3:201-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 9. Liaghat B, Pedersen JR, Husted RS, Pedersen LL, Thorborg K, Juhl CB. Diagnosis, prevention and treatment of common shoulder injuries in sport: Grading the evidence – a statement paper commissioned by the Danish Society of Sports Physical Therapy (DSSF). Br J Sports Med 2023;57:408-16. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 10. Luenam S, Kosiyatrakul A. Massive rotator cuff tear associated with acute traumatic posterior shoulder dislocation: Report of two cases and literature review. Musculoskelet Surg 2013;97:273-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 11. Brelin A, Dickens JF. Posterior shoulder instability. Sports Med Arthrosc Rev 2017;25:136-43. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 12. Robinson CM, Seah M, Akhtar MA. The epidemiology, risk of recurrence, and functional outcome after an acute traumatic posterior dislocation of the shoulder. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2011;93:1605-13. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 13. Schoenfeld AJ, Lippitt SB. Rotator cuff tear associated with a posterior dislocation of the shoulder in a young adult: A case report and literature review. J Orthop Trauma 2007;21:150-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 14. Kammel KR, El Bitar Y, Leber EH. Posterior shoulder dislocations. In: StatPearls. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing; 2025. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/nbk441919 [Last accessed on 2025 Jun 13]. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 15. Abrams R, Akbarnia H. Shoulder dislocations overview. In: StatPearls. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing; 2025. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/nbk459125[Last accessed on 2025 Jun 13]. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 16. Saupe N, White LM, Bleakney R, Schweitzer ME, Recht MP, Jost B, et al. Acute traumatic posterior shoulder dislocation: MR findings. Radiology 2008;248:185-93. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 17. Perron AD, Jones RL. Posterior shoulder dislocation: Avoiding a missed diagnosis. Am J Emerg Med 2000;18:189-91. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 18. Soon EL, Bin Abd Razak HR, Tan AH. A rare case of massive rotator cuff tear and biceps tendon rupture with posterior shoulder dislocation in a young adult – surgical decision-making and outcome. J Orthop Case Rep 2017;7:82-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 19. Festbaum C, Minkus M, Akgün D, Hupperich A, Maier D, Auffarth A, et al. Conservative treatment of acute traumatic posterior shoulder dislocations (Type A) is a viable option especially in patients with centred joint, low gamma angle, and middle or old age. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2022;30:2500-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 20. Paul J, Buchmann S, Beitzel K, Solovyova O, Imhoff AB. Posterior shoulder dislocation: Systematic review and treatment algorithm. Arthroscopy 2011;27:1562-72. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 21. Verma NN, Sellards RA, Romeo AA. Arthroscopic reduction and repair of a locked posterior shoulder dislocation. Arthroscopy 2006;22:1252.e1-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 22. Goubier JN, Duranthon LD, Vandenbussche E, Kakkar R, Augereau B. Anterior dislocation of the shoulder with rotator cuff injury and brachial plexus palsy: A case report. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2004;13:362-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 23. “Crash Dashboard.” Florida Department of Highway Safety and Motor Vehicles; 2019. Available from: https://www.flhsmv.gov/traffic-crash-reports/crash-dashboard [Last accessed on 2025 Jun 13]. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 24. Traffic Crash Statistics Report 2010 – Florida Highway Safety and Motor. Available from: https://www.flhsmv.gov/pdf/crashreports/crash_facts_2010.pdf [Last accessed on 2025 Jun 13]. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]