Implant selection in pertrochanteric fractures should be guided by fracture stability. While short PFNs are effective in stable fractures, long PFNs are biomechanically superior in unstable configurations and reduce complication risk.

Dr. Saurabh Damkondwar, Department of Orthopaedics, Government Medical College, Chhatrapati Sambhajinagar, Maharashtra, India. E-mail: saurabhdamkondwar@gmail.com

Introduction: Pertrochanteric femur fractures are common in elderly patients with osteoporosis. Cephalomedullary nails are the standard of care, but the choice between short and long proximal femoral nails (PFNs) remains debated.

Materials and Methods: We present a case series of 30 patients with pertrochanteric fractures treated at our institute between January 2023 and December 2024. Fifteen patients were managed with short PFN and fifteen with long PFN. Functional and radiological outcomes were assessed using Harris hip score, time to union, complication rate, and post-operative mobilization. Long PFNs showed faster union (14.6 ± 1.4 weeks vs. 16.3 ± 1.7 weeks), earlier mobilization, and fewer complications (20% vs. 46.7%). Short PFNs had shorter operative times and lower intraoperative blood loss. Illustrative cases are presented, including implant failures requiring salvage with total hip replacement.

Conclusion: Short PFNs are adequate for stable pertrochanteric fractures, but long PFNs provide superior stability and fewer complications in unstable patterns.

Keywords: Femoral neck fracture, working length, neck of femur fracture, proximal femoral nail, intertrochanteric, proximal femoral nail, cephalomedullary nail.

Pertrochanteric femur fractures are among the most frequent injuries in the elderly population, often associated with osteoporosis and high morbidity [1,2]. Early surgical stabilization allows rapid mobilization and reduces complications such as pneumonia, deep vein thrombosis, and muscle wasting [1,2]. Cephalomedullary nails (CMNs) are now considered the gold standard, offering minimally invasive fixation with strong biomechanical support [1,3].

Short proximal femoral nails (PFNs) are technically easier to insert, with reduced operative time and blood loss [4]. However, their shorter working length may predispose to peri-implant fractures, varus collapse, and implant cut-out [2,5]. Long PFNs, on the other hand, distribute load over a greater length of the femoral shaft and reduce mechanical complications [5,6], though at the expense of longer operative time and more blood loss [4].

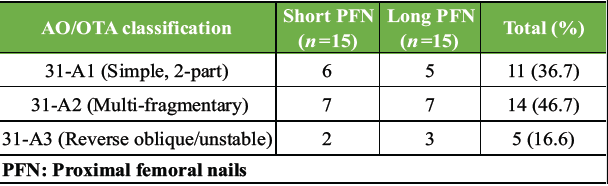

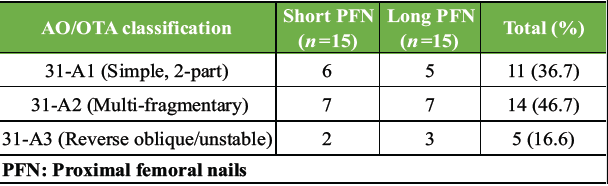

This article reports our institutional experience with 30 patients, highlighting the clinical implications of implant choice, supported by illustrative cases [7,8].The distribution of fracture patterns and implant selection is summarized in Table 1.

Table 1: Distribution of patients by AO/OTA classification

Table 1: Distribution of patients by AO/OTA classification

We retrospectively reviewed 30 patients with pertrochanteric femur fractures treated between January 2023 and December 2024. Fifteen patients underwent fixation with short PFN and fifteen with long PFN. Inclusion criteria were patients aged >18 years with pertrochanteric femur fractures. Pathological fractures, polytrauma cases, and those with inadequate follow-up were excluded.

In our study, short PFNs were preferentially used in stable fracture configurations (AO/OTA 31-A1 to A2.1) with preserved lateral wall integrity and adequate medial cortical support, where the primary goal was rapid fixation with minimal operative blood loss. Long PFNs were selected for unstable patterns (AO/OTA 31-A2.2 to A3), fractures with subtrochanteric extension, reverse obliquity morphology, posteromedial comminution, lateral wall deficiency, or in osteoporotic bone at higher risk of peri-implant fracture, as longer constructs were biomechanically advantageous in dissipating load along the shaft. This selection was based on careful pre-operative radiological assessment and intraoperative evaluation of fracture stability and bone quality.

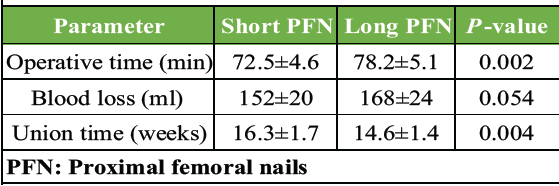

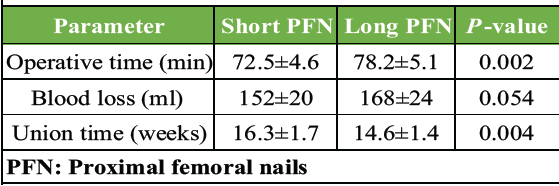

Parameters studied included operative time, blood loss, time to mobilization, Harris hip score at 3, 6, and 12 months, fracture union, and complications. Operative time, blood loss, and union time comparisons are shown in Table 2.

Table 2: Operative and clinical parameters

Table 2: Operative and clinical parameters

Research instrument

Clinical effects of working length of CMN in pertrochanteric femur fractures.

Patient demographics

(Clinical and demographic variables overlapped equally between both groups, consistent with the fracture-type distribution shown in Table 1.)

- Study ID/Case No.-

- Name/Age/Sex-

- Hospital ID-

- Date of surgery-

- Side involved (Right/Left).

Clinical details

- Fracture type (AO/OTA classification)-

- Nail used (Short/Long PFN)-

- Surgery duration (mins)-

- Length of hospital stay (days)-

- Other clinical notes.

Inclusion/exclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria: ✔/✘

- Pertrochanteric femur fracture

- Short/long PFN used

- ≥9 months follow-up.

Exclusion criteria: ✔/✘

- Pathological fracture/metastasis

- Not willing for surgery

- Unfit for surgery

- Other fracture type

- Polytrauma

- Incomplete records/inadequate follow-up.

Post-operative recovery

(Early post-operative recovery patterns, including time to mobilization and physiotherapy duration, are summarized in Table 3.)

Table 3: Duration of recovery time

Table 3: Duration of recovery time

- Pain level (Visual Analog Scale score)-

- Mobility status-

Functional outcomes

(Functional outcomes including range of motion and deformity parameters followed expected trends corresponding to the union times shown in Table 2.)

- Parameters assessed: Pain, function, absence of deformity, and range of motion.

- Score ranges: <70 Poor|70–79 Fair|80–89 Good|90–100 Excellent

- Pain (0–44)-

- Function (0–47)-

- Absence of deformity (0–4)-

- Range of motion (0–5).

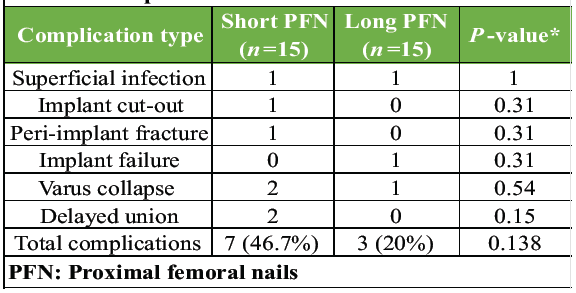

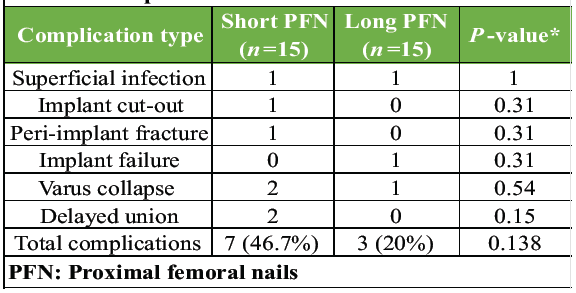

Implant related complications

(Complications such as varus collapse, cut-out, peri-implant fractures, or implant failure were recorded and compared between groups (details in Table 4).

Table 4: Complications

Table 4: Complications

- Hardware failure Yes/No

- Screw cut-out Yes/No

- Breakage Yes/No

- Nail migration Yes/No.

Fracture union

- Radiological union date

- Clinical union date

- Total union time (weeks)

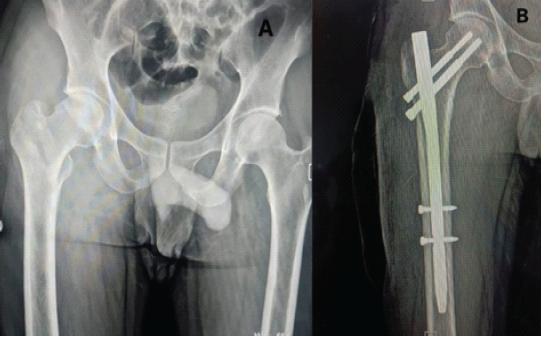

Illustrative cases

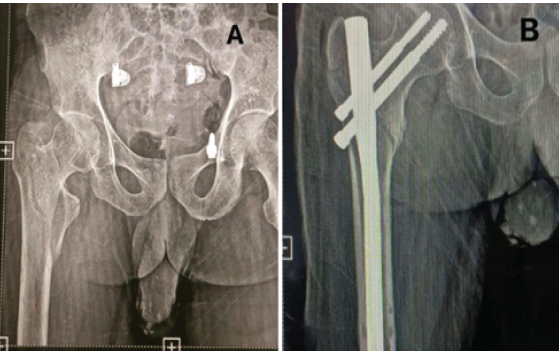

Case 1

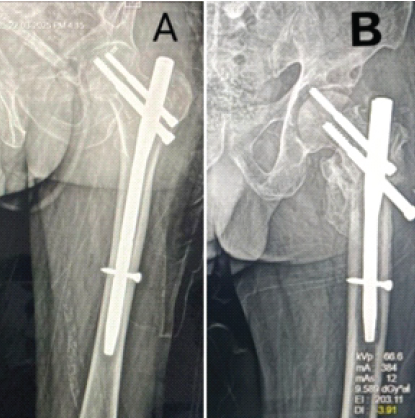

A 30-year-old male patient with TYPE 31-A1.2 pertrochanteric femur fracture of the right side (Fig. 1).

Figure 1: (a) Pre-operative anterior-posterior (A-P) view X-ray showing TYPE 31-A1.2 pertrochanteric femur fracture of the right side. (b) Post-operative A-P view X-ray showing pertrochanteric femur fracture fixed with short proximal femur nail.

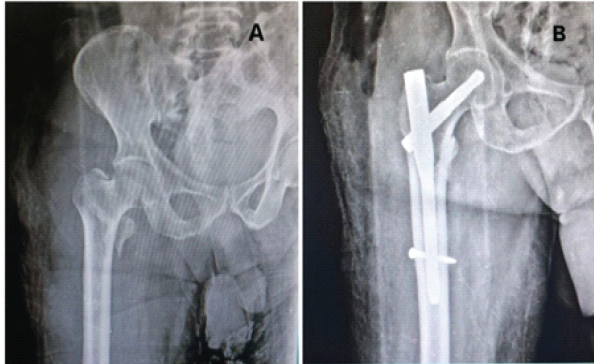

Case 2

A 55-year-old male patient with TYPE 31-A2.1 pertrochanteric femur fracture of the right side (Fig. 2).

Figure 2: (a) Pre-operative anterior-posterior (A-P) view X-ray showing TYPE 31-A2.1 pertrochanteric femur fracture of the right side. (b) Post-operative A-P view X-ray showing pertrochanteric femur fracture fixed with long proximal femur nail.

Case 3

An 80-year-old male patient with TYPE 31-A2.1 pertrochanteric femur fracture of the right side (Fig. 3).

Figure 3: (a) Pre-operative anterior-posterior (A-P) view X-ray showing TYPE 31-A2.1 pertrochanteric femur fracture of the right side. (b) Post-operative A-P view X-ray showing pertrochanteric femur fracture fixed with short proximal femur nail.

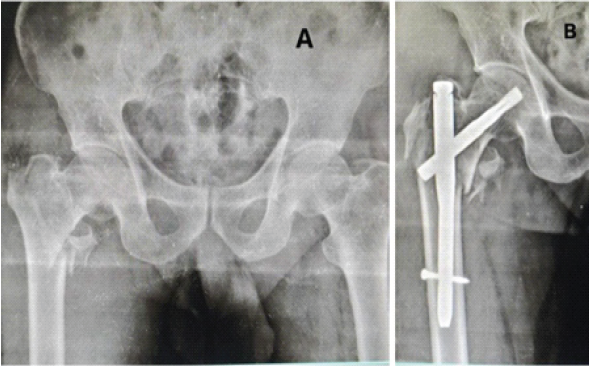

Case 4

A 60-year-old male patient with TYPE 31-A2.2 pertrochanteric femur fracture of the right side (Fig. 4).

Figure 4: (a) Pre-operative anterior-posterior (A-P) view X-ray showing TYPE 31-A2.2 pertrochanteric femur fracture of the right side. (b) Post-operative A-P view X-ray showing pertrochanteric femur fracture fixed with short proximal femur nail.

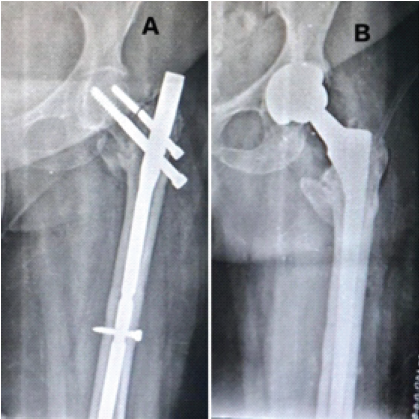

Case 5

A 70-year-old female with a long PFN presented with screw breakage at 5 months, requiring revision to total hip replacement (Fig. 5).

Figure 5: (a) 5 months post-operative anterior-posterior (A-P) view X-ray showing screw-breakage in pertrochanteric femur fracture of the left side fixed with short proximal femoral nail. (b) Post-operative A-P view X-ray showing total hip replacement done after implant removal.

Case 6

A 65-year-old male patient with an operated left pertrochanteric fracture presented 5 months post-operatively with a classical “Z” effect of proximal femoral nail (Fig. 6).

Figure 6: (a) Post-operative anterior-posterior (A-P) view X-ray showing pertrochanteric femur fracture of the left side fixed with a short proximal femoral nail. (b) Post-operative A-P view X-ray showing “Z” effect of proximal femur nail.

• Union time: Long PFN group (14.6 ± 1.4 weeks) versus short PFN group (16.3 ± 1.7 weeks), P = 0.004. Table 2

Table 2: Operative and clinical parameters

• Operative time: Slightly longer in long PFN group (78.2 min vs. 72.5 min, P = 0.002).Table 2

• Complications: 46.7% in the short PFN versus 20% in the long PFN group. Table 4

Table 4: Complications

• Mobilization: Patients with long PFN ambulated earlier (5–7 days vs. 7–9 days).Table 3

Table 3: Duration of recovery time

5. Fracture type distribution (A1/A2/A3) between groups is presented in Table 1, forming the basis for implant selection.

Table 1: Distribution of patients by AO/OTA classification

The concept of working length plays a pivotal role in understanding the biomechanical performance of CMNs. Working length refers to the effective segment of the nail spanning the fracture site and contributing to stress distribution during axial and rotational loading [1]. A shorter working length, as seen with short PFNs, concentrates mechanical forces near the proximal femur, increasing the risk of varus collapse, peri-implant fracture, and screw cut-out in unstable fracture patterns [7]. In contrast, long PFNs offer a greater working length, resulting in more uniform stress dispersion along the femoral shaft and superior resistance to deformation [5].

This difference in load-sharing alters the biological environment of fracture healing. Short nails may permit excessive micromotion at the fracture site in unstable configurations, predisposing to delayed union or nonunion [7]. Long PFNs provide better axial control and controlled micromotion, which supports callus formation and more predictable healing outcomes [5]. These biomechanical advantages are especially relevant in comminuted, reverse oblique, or subtrochanteric extension fractures, where the extended working length of a long PFN acts as a more effective load-bearing construct [1,5]. In our series, long PFNs provided superior outcomes in unstable fracture patterns, with faster union (14.6 ± 1.4 weeks vs. 16.3 ± 1.7 weeks, P = 0.004), earlier mobilization (5–7 days vs. 7–9 days), and fewer complications (20% vs. 46.7%) as sown in Table 2, 3, 4. This aligns with previous studies indicating that long PFNs distribute load over a greater femoral length, reduce varus collapse, and lower the risk of peri-implant fractures in unstable configurations [1,3,4,7,6]. Biomechanical simulations have shown that longer working lengths increase construct stability, particularly in reverse oblique and multifragmentary fractures [6].

Short PFNs remain effective for stable fractures (AO/OTA 31-A1), providing reduced operative time (72.5 min vs. 78.2 min, P = 0.002) and lower intraoperative blood loss as demonstrated in Table 2. These advantages make them suitable in resource-limited settings or in patients with comorbidities where operative morbidity must be minimized [1,7,8]. However, caution is warranted in unstable fracture patterns, as higher mechanical failure rates have been reported with short nails [1,7,5].

In our series, the mean length of the long PFN used was 360–400 mm, whereas the mean length of the short PFN was 250 mm, with a uniform diameter of 10 mm chosen according to femoral canal morphology and reaming tolerance. These findings are comparable to those reported by Shannon et al. [3], who demonstrated similar shaft engagement principles in long nails conferring improved rotational control and reduced peri-implant stress, and by Selim et al. [1], who noted that a diameter of 9–10 mm optimizes intramedullary canal fill while minimizing iatrogenic cortical splitting. Das et al. [7] also observed that longer nails with adequate medullary fit generate better axial stability in unstable pertrochanteric fractures, supporting our radiological union trends. Rahman et al. [4] further highlighted that longer implants reduce stress risers at the distal tip, decreasing the risk of secondary femoral fractures, while Tan et al. [8] in a meta-analysis confirmed the biomechanical advantage of longer constructs in preventing varus collapse and re-operation in unstable fracture patterns.

Complication management is an important consideration. In our study, short PFNs showed a higher incidence of peri-implant fractures, varus collapse, and need for revision surgery, as shown in Table 4. These complications increase patient morbidity and healthcare costs, reinforcing the need for careful pre-operative assessment and implant selection [2,5,10].

Both short and long PFNs provide reliable fixation in pertrochanteric femur fractures. Short PFNs are adequate for stable fracture configurations, offering reduced operative time and lower intraoperative morbidity. In contrast, long PFNs are biomechanically superior in unstable fractures, leading to faster union, earlier mobilization, and fewer complications. Careful pre-operative assessment of fracture stability is essential to guide implant selection and optimize patient outcomes.

Implant choice in pertrochanteric fractures should be individualized. Long PFNs are recommended for unstable patterns to enhance mechanical stability and reduce complication risk, while short PFNs remain appropriate for stable fractures where operative morbidity and technical ease are priorities.

References

- 1. Selim AA, El-Ganainy S, El-Boghdady M, Ahmed AR, El-Sherbiny M, Hassan A, et al. Management of unstable pertrochanteric fractures: A review of treatment options and outcomes. SICOT J. 2020;6:8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 2. Haslhofer DJ, Kerschbaum M, Gabl M, Schmid R, Benedetto KP, Weninger P, et al. Complication rates after proximal femoral nailing in pertrochanteric fractures: A single-center experience. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg. 2023;49:507–13. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 3. Shannon SF, McGwin G, McGwin J, Ponce BA, O’Toole RV, Hsu JR, et al. Short versus long cephalomedullary nails for pertrochanteric hip fractures: A randomized controlled trial. J Orthop Trauma. 2019;33:480–6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 4. Rahman MA, Rahman MM, Rahman MM, Islam MS, Alam MS, Sarker MA, et al. Short versus long proximal femoral nail in the management of intertrochanteric fractures: A prospective randomized study. Int J Biol Med Res. 2023;13:1414–20. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 5. Parola R, Gagliardi G, Lippiello M, Longo UG, Denaro V, Meccariello L, et al. Quality differences in multifragmentary pertrochanteric fractures treated with short versus long cephalomedullary nails. Injury. 2022;53:1042–7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 6. Boonyanuwat W, Sutharoj T, Suksathit S, Rungprai C, Chareancholvanich K, Pornrattanamaneewong C, et al. Comparative efficacy of short and long cephalomedullary nails in pertrochanteric fractures: A randomized controlled trial. Injury. 2025;56:765–73. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 7. Das C, Yadav S, Sharma A, Gupta A, Singh S, Kumar P, et al. Functional outcome of long proximal femoral nail versus short proximal femoral nail in the treatment of pertrochanteric fractures. Indian J Orthop. 2022;56:56–62. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 8. Tan GK, Tan SH, Tan YH, Lee KB, Goh SK, Yeo NE, et al. Clinical outcomes following long versus short cephalomedullary nails in the treatment of pertrochanteric fractures: A meta-analysis. Sci Rep. 2021;11:20762. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 9. Udin G, Lutz M, Soni A, Rieger M, Schwendinger P, Erhart J, et al. Long versus short intramedullary nails for reverse pertrochanteric fractures: A biomechanical simulation study. Injury. 2024;55:1045–50. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 10. Lee KB, Lee BT, Park YH, Choi HS, Kim JH, Lee HS, et al. Complications of femoral pertrochanteric fractures treated with proximal femoral nail. J Korean Fract Soc. 2007;20:33–9 [Google Scholar] [PubMed]