Meticulous surgical technique – especially maintaining central implant placement, bi-cortical distal fixation, and slight valgus alignment – is crucial for optimal outcomes and minimizing complications in femoral neck fracture fixation using the Femoral Neck System.

Dr. Ramesh Govindharaaju, Department of Orthopaedics, Government Medical College, Kozhikode, Kerala, India. E-mail: rams.osum@gmail.com

Introduction: Femoral neck fractures continue to challenge orthopedic surgeons due to their complex biomechanics, high shear stresses, and risk of avascular necrosis (AVN) or non-union. The Femoral Neck System (FNS) is a relatively newer fixed-angle device designed to enhance stability while minimizing soft-tissue damage. This case series presents our clinical experience with the FNS across a spectrum of femoral neck fractures, focusing on technical nuances and lessons that influenced our patients’ outcomes.

Materials and Methods: Eight patients (aged 24–66 years) with femoral neck fractures of varying Garden and Pauwel types were managed with the FNS. Fracture patterns ranged from stable valgus-impacted to high-energy displaced fractures, including cases with concomitant pelvic or shaft injuries. Stable, valgus-impacted fractures treated with in situ fixation and minimal compression consistently achieved union and excellent function by 3 months. Displaced and vertical fractures united reliably when near-anatomical or valgus reduction with central implant placement and bi-cortical distal fixation was achieved. Technical errors such as anterior or eccentric bolt placement, unicortical distal locking, or correction of valgus to neutral alignment were associated with complications including varus collapse, implant back out, and neck shortening. One young patient developed AVN following high-energy trauma despite satisfactory fixation.

Conclusion: The FNS offers a stable and minimally invasive option for femoral neck fracture fixation when applied with precise technique and respect for fracture morphology in selected cases. In situ or slight valgus fixation, especially in osteoporotic bone, yields superior outcomes due to the FNS’s invasive nature, avoidance of rotational torque to the at-risk head fragment and retention of the inherently stable valgus or neutral alignment. Complications were largely attributable to mechanical and technical factors rather than implant design, highlighting the importance of meticulous surgical planning and execution and careful patient selection.

Keywords: Femoral neck system, femoral neck fracture, internal fixation, avascular necrosis, varus collapse.

Adult femoral neck fractures are commonly encountered hip injuries, especially in the elderly and can cause significant morbidity if not managed appropriately. The management protocol varies according to the age of the patient, status of medical co-morbidities, time since injury, and many other factors. Although there is no set age limit, younger patients are given a trial of fracture fixation initially, as the femoral neck has a higher healing potential in younger patients, and if the fixation fails, a secondary replacement surgery is still possible without the risks of multiple surgeries associated with operating on elderly patients with multiple comorbidities. Femoral neck fractures can be fixed with a range of implants including cannulated cancellous screws (CCS), the Dynamic Hip Screw (DHS), proximal femoral nails, and the relatively newer implant – Femoral Neck system (FNS). Several studies claim that the FNS is biomechanically equivalent or superior to the DHS and the commonly used three-CC screw-construct [1,2]. Being a fixed angle device with a side plate, smooth blade, barrel, and an anti-rotation screw and distal locking screws, it is said to be superior to the three CC screw construct in terms of stability and produces less rotational torque than the DHS head screw during insertion, which is a known risk factor for causing avascular necrosis (AVN) of the head of femur.

In this article, we seek to share our experience with the FNS in managing different types of femoral neck fractures in patients from different age groups, highlighting the factors which lead to successful fracture union, and those that could lead to varus collapse, non-union or AVN. In spite of the availability of a large volume of comparative studies and systematic reviews on the usage of the FNS, individual analysis of each case for the reasons for successful union, failure to unite, varus collapse, and implant or surgeon-related factors with descriptive intraoperative and post-operative images is not widely available. This article aims to provide the above in a concise manner so as to guide surgeons in their management of femoral neck fractures with the FNS.

Case 1

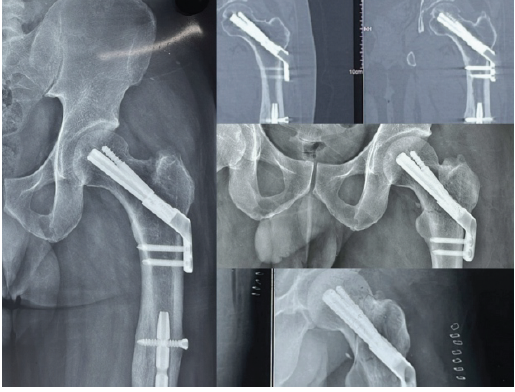

A 66-year-old female presented with a valgus-impacted Garden’s type I, Pauwel’s type I femoral neck fracture after a low-energy fall. Fixation was done in situ with the FNS device, applying mild compression and without any reduction maneuver. The blade and anti-rotation screw were positioned centrally with adequate tip-apex distance, and bi-cortical distal locking screws were used. By 3 months, radiographs showed complete bony union, and the patient returned to full function (Fig. 1). The good outcome could be attributed to the stable fracture pattern, early intervention, and favorable implant positioning.

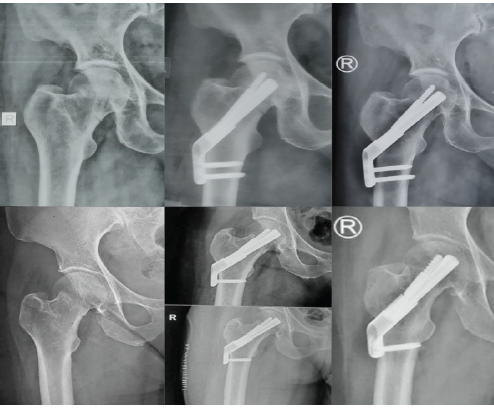

Figure 1: Top left: pre-operative radiograph of Case 1; top center: immediate post-operative radiograph; top right: post-operative radiograph at 3 months. Bottom left – pre-operative AP radiograph of Case 2; bottom center – immediate post-operative radiograph; bottom right: post-operative radiographs at 3 months.

Case 2

A 64-year-old female sustained a valgus-impacted Garden’s type I, Pauwel’s type I fracture. Similar to the previous case, the fracture was fixed in situ with compression using the FNS device, with central implant placement and bi-cortical distal locking. At 3 months, complete union was observed, and functional recovery was achieved (Fig. 1). The predictable healing here may reflect the inherent stability of valgus-impacted fractures combined with timely fixation.

Case 3

A 54-year-old male presented with a Garden’s type III, Pauwel’s type III fracture after a low-energy injury. Closed reduction with minimal traction achieved near-anatomical alignment, followed by fixation with mild compression. Implant placement was satisfactory, with a good tip-apex distance and bi-cortical distal locking. At 3 months, complete union was seen with only minimal neck shortening (Fig. 2), and the patient regained full function. Younger age, good bone quality, and near-anatomical reduction were likely helpful in achieving this result in spite of a vertical fracture pattern (Pauwel’s type III).

Figure 2: Top left: Pre-operative, intraoperative C-arm images and immediate post-operative radiographs of Case 3; Bottom left and right: post-operative radiographs at 3 months

Case 4

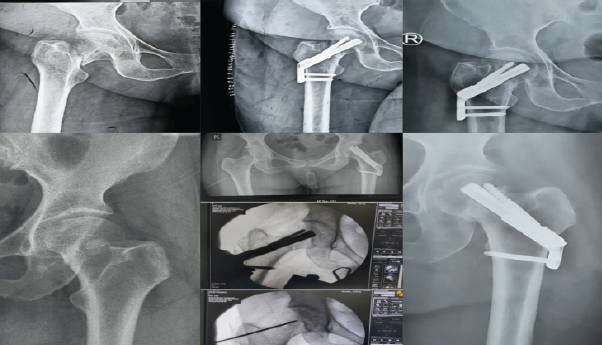

A 24-year-old male sustained a high-energy injury with multiple pelvic fractures in addition to a displaced Garden’s type IV, Pauwel’s type III femoral neck fracture. Mild traction and valgus fixation with compression were achieved using the FNS, with adequate positioning of the blade and anti-rotation screw and bi-cortical distal locking. The patient was lost to follow-up as he was a native of West Bengal. However, we established contact with the patient after 12 months and his latest X-Rays showed that the fracture had united, but by 16 months AVN of the femoral head with secondary degenerative changes developed (Fig. 3). The displacement, comminution, high-energy mechanism, and possible early return to weight-bearing may have contributed to this complication, despite good implant placement and good bone quality.

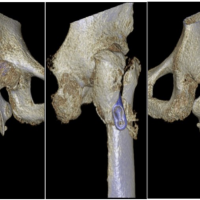

Figure 3: (Case 4) Top right: Pre-operative 3D computed tomography image showing supero-postero-lateral neck comminution; Centre-right: Immediate post-operative AP radiograph; bottom row: intraoperative C-arm images; Top left: 16 months post-operative radiographs showing fracture union and osteoarthritis hip changes secondary to AVN

Case 5

A 35-year-old male with intellectual disability sustained a displaced Garden’s type IV, Pauwel’s type II fracture. Fixation was performed with the FNS, but with only a single unicortical distal locking screw at the level of the cancellous lesser trochanter, and the anti-rotation screw locking mechanism failed, leading to backout. By 15 months, radiographs showed radiolucency and reactive bone formation around the implant, though infection was excluded clinically and with laboratory investigations. The radiographs also revealed generalized osteopenia with thinned out femoral diaphyseal cortices. A Bone Mineral Density scan was done which also revealed osteopenia (T-score – 1.8) (Fig. 4). Hence, factors that might have contributed include poor bone quality, mechanical insufficiency due to unicortical fixation, and possible abnormal femoral version and early weight-bearing on the patient’s side. The patient is now being counseled to undergo a total hip replacement.

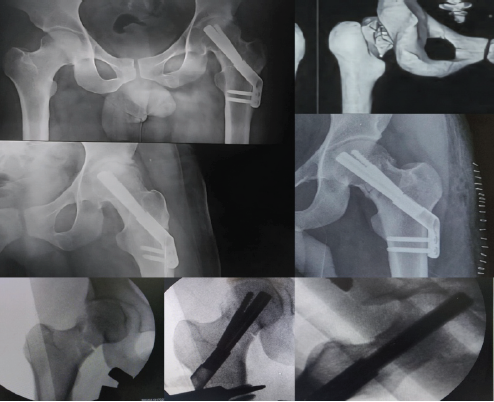

Figure 4: Top left: Pre-operative radiographs of Case 5; Bottom row: immediate post-operative radiographs; top right: follow-up radiographs at 15 months showing fixation failure, non-union, and screw backout.

Case 6

A 34-year-old male sustained a high-energy femoral shaft fracture with a concomitant low-energy, undisplaced, basicervical Garden’s type I, Pauwel’s type II femoral neck fracture. The neck fracture was stabilized anatomically in situ with compression using the FNS, with good implant positioning but a slightly lower tip-apex distance. At 5 months, the femoral neck had united (confirmed with computed tomography) (Fig. 5), but the shaft fracture had gone into non-union, for which exchange nailing and grafting were planned.

Figure 5: Radiographs (left) and computed tomography (top right) confirming complete fracture union in Case 6. Bottom center and right: immediate post-operative radiographs.

Case 7

A 60-year-old female with osteoporosis sustained a displaced Garden’s type IV, Pauwel’s type III fracture. The fracture was fixed in neutral position with the FNS device, but the bolt and anti-rotation screw were placed too anteriorly, leaving a superolateral void at the head–neck junction. Although union was achieved at 5 months, the fracture underwent varus collapse and significant neck shortening, with radiographs showing a widening gap between the plate and lateral femoral cortex compared to immediate post-operative images (Fig. 6). This case emphasizes the importance of central implant positioning and valgus fixation in osteoporotic bone and perhaps a lower threshold for choosing replacement over fixation in osteoporotic bone.

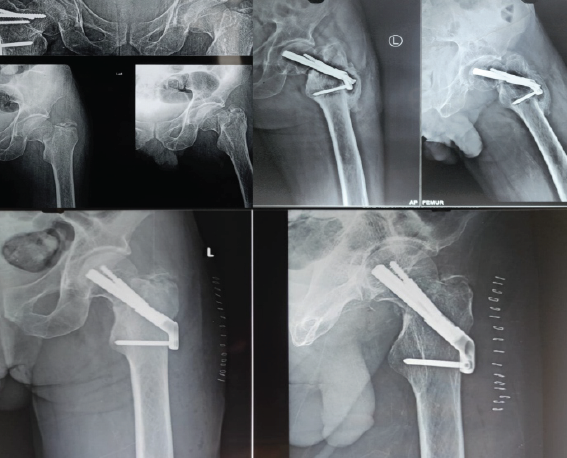

Figure 6 Top left: Pre-operative radiographs of Case 7; top center: immediate post-operative AP radiograph of the fracture; top right: union with a shortened neck and varus collapse. Bottom left: Pre-operative radiograph of Case 8; bottom center: Intraoperative C-arm images following reduction to neutral- clearly showing a supero-lateral bony void; bottom right: varus collapse and neck shortening noticed at 7 months.

Case 8

A 66-year-old female sustained a valgus-impacted Garden’s type I, Pauwel’s type I fracture. During fixation, an attempt was made to correct the valgus to a neutral position, which created a superolateral void and reduced anti-rotation screw purchase. This destabilized the lateral hinge and predisposed the fracture to collapse. By 7 months, the fracture underwent varus collapse and shortening, evident from reduced space between the lateral end of the bolt and barrel compared to immediate post-operative images (Fig. 6). In hindsight, in situ fixation or valgus fixation would likely have been preferable in such cases.

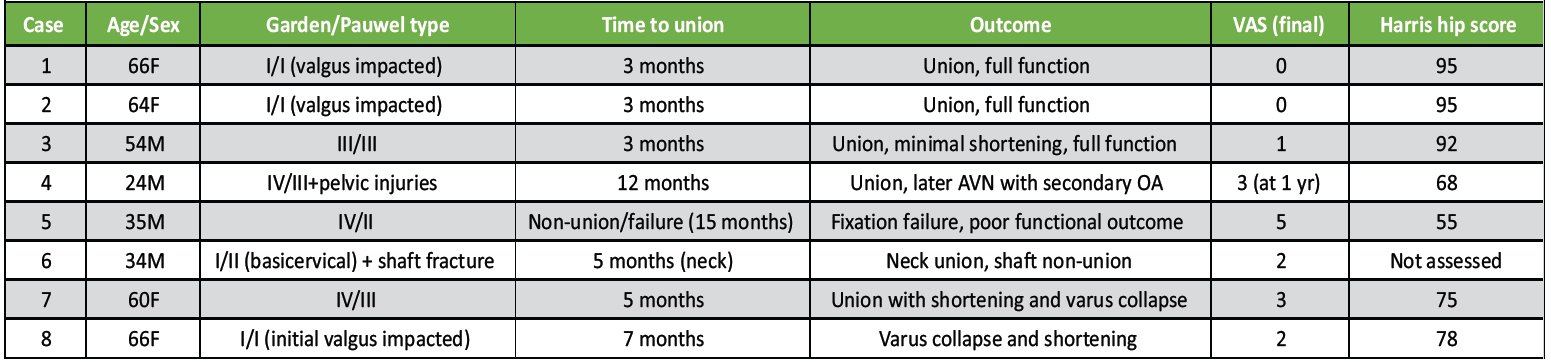

This series illustrates a wide spectrum of femoral neck fractures managed with the FNS, ranging from stable valgus-impacted fractures in elderly patients to high-energy displaced fractures in young adults with associated injuries. Patient demographics, fracture type and classification, time to fracture union, and post-operative outcomes from the above eight cases have been summarized in a table (Table 1).

Table 1: Summary of fracture type, union time, and functional outcomes after Femoral Neck System fixation, including final VAS and Harris Hip scores.

Across all cases, several patterns and learning points emerge. Femoral neck fractures in adults, particularly those under 60 years of age, continue to pose a challenge because of their unique blood supply, shear stresses, and the risk of non-union or AVN. While CCS and the DHS have been traditional options, the FNS represents a recent advancement designed to enhance construct stability and simplify fixation.

Stoffel et al. [2] established the biomechanical superiority of the FNS compared with both DHS and CCS in unstable Pauwels III fractures, citing higher axial and torsional stability owing to its fixed-angle bolt-plate construct and controlled compression. The biomechanical rationale aligns with the broader principles outlined by Panteli et al., who emphasized that angular-stable devices better resist shear in non-elderly patients with high Pauwels-angle patterns [3]. Hu et al. reported that patients younger than 60 years achieved satisfactory outcomes with either CCS or FNS, but the FNS group demonstrated superior construct stability and lower rates of shortening [4]. Likewise, Yan et al. found that the FNS reduced fluoroscopy exposure, femoral neck shortening, and implant migration compared with the three-CC screw construct [5]. In comparative studies, Tang et al. and Zhou et al. also noted earlier union and less shortening in the FNS cohort, confirming its clinical reliability in unstable configurations [6,7]. A recent prospective Indian series by Kumar et al. involving 84 patients further supported these findings, demonstrating improved functional and radiological outcomes with the poly-axial screw-in-bolt construct (analogous to the FNS) compared with multiple cancellous screws [8]. Despite these advantages, complications persist. Slobogean et al. highlighted the high complication burden – non-union, fixation failure, and AVN – in young femoral neck fractures, often influenced by comminution and technical error [9]. Han et al. confirmed that comminution in displaced or Pauwels III fractures independently increases postoperative complications and delays recovery [10]. These findings emphasize the need for precise reduction, stable fixation, and avoidance of excessive varus alignment. Our case series reflects these observations. Undisplaced or valgus-impacted fractures (Garden I, Pauwels I) consistently united with in situ fixation and mild compression using the FNS, echoing the predictable healing patterns noted by Hu et al. and Yan et al. The rigid angular stability and controlled compression of the FNS likely contributed to these outcomes while minimizing soft-tissue disruption and fluoroscopy time. Conversely, displaced fractures (Garden III/IV, Pauwels II/III) required accurate anatomical to valgus reduction to counteract shear. When reduction and central implant placement were achieved, union was reliable – even in high-shear patterns – consistent with biomechanical data from Stoffel et al. [2] Complications in our series – such as varus collapse, neck shortening, and implant backout – correlated strongly with technical factors. Anterior or off-center bolt placement and unicortical distal locking reduced the lateral buttress effect and permitted collapse, findings also stressed by Zhou et al. [7]. Similarly, attempts to neutralize valgus-impacted fractures by converting them to neutral alignment created a superolateral void and precipitated varus collapse – an intraoperative pitfall highlighted by our experience. In osteoporotic bone, maintaining slight valgus alignment appears biomechanically safer and consistent with the literature’s emphasis on preserving cortical contact. Bone quality and patient factors were equally decisive. Osteoporosis and mechanical insufficiency, as in one case with unicortical fixation, led to non-union despite adequate initial alignment. Younger patients with good bone stock, however, demonstrated rapid healing, reinforcing that host biology and implant mechanics are co-determinants of outcome. Associated injuries, such as femoral shaft or pelvic fractures, did not preclude femoral neck union when the FNS was correctly applied – suggesting that the stability provided by the device is sufficient even under complex load conditions. These intraoperative advantages mirror our clinical impressions, though the economic burden remains a limitation in low-resource environments, as observed by Kumar et al. [8].

Overall, the FNS provided reliable fixation across a spectrum of femoral neck fractures when used with appropriate technique and attention to fracture and patient factors. Complications largely arose from either fracture-related risk factors or technical nuances in implant positioning, emphasizing the educational value of careful surgical planning and execution.

Successful outcomes with the Femoral Neck System depend not only on its design but also on an individualized approach to each fracture and patient. Recognizing subtle differences in fracture morphology and respecting native alignment – especially preserving valgus in stable patterns – can prevent avoidable complications and promote fracture union, thereby ensuring good functional outcomes.

References

- 1. Park YC, Um KS, Kim DJ, Byun J, Yang KH. Comparison of femoral neck shortening and outcomes between in situ fixation and fixation after reduction for severe valgus-impacted femoral neck fractures. Injury 2021;52:569-74. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 2. Stoffel K, Zderic I, Gras F, Sommer C, Eberli U, Mueller D, et al. Biomechanical evaluation of the femoral neck system in unstable Pauwels III femoral neck fractures: A comparison with the dynamic hip screw and cannulated screws. J Orthop Trauma 2017;31:131-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 3. Panteli M, Rodham P, Giannoudis PV. Biomechanical rationale for implant choices in femoral neck fracture fixation in the non-elderly. Injury 2015;46:445-52. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 4. Hu H, Cheng J, Feng M, Gao Z, Wu J, Lu S. Clinical outcome of femoral neck system versus cannulated compression screws for fixation of femoral neck fracture in younger patients. J Orthop Surg Res 2021;16:370. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 5. Yan SG, Cui Y, Li D, Liu F, Hua X, Schmidutz F. Femoral neck system versus three cannulated screws for fixation of femoral neck fractures in younger patients: A retrospective cohort study. J Invest Surg 2023;36:2266752. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 6. Tang Y, Zhang Z, Wang L, Xiong W, Fang Q, Wang G. Femoral neck system versus inverted cannulated cancellous screw for the treatment of femoral neck fractures in adults: A preliminary comparative study. J Orthop Surg Res 2021;16:504. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 7. Zhou XQ, Li ZQ, Xu RJ, She YS, Zhang XX, Chen GX, et al. Comparison of early clinical results for femoral neck system and cannulated screws in the treatment of unstable femoral neck fractures. Orthop Surg 2021;13:1802-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 8. Kumar V, Agrawal GK, Siwach K, Siwach RC, Therattil P, Garg AM, et al. Prospective randomised study comparing functional and radiological outcomes of fracture neck of femur fixation using poly-axial screw in bolt construct versus multiple cancellous screws. J Orthop Rep 2025;4:100323. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 9. Slobogean GP, Sprague SA, Scott T, Bhandari M. Complications following young femoral neck fractures. Injury 2015;46:484-91. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 10. Han M, Li C, Han N, Sun G. Safe range of femoral neck system insertion and the risk of perforation. J Orthop Surg Res 2023;18:703. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]