The forced drop leg test (FDLT) is an intraoperative method designed to dynamically check femoroacetabular joint stability during total hip replacement (THR). Unlike conventional assessments, the FDLT rigorously assesses the hip’s resistance to dislocation by simulating high-risk movements—ensuring stability during the most extreme of movement. This technique fills a vital gap in surgical practice by enabling the real-time optimization of implant positioning and component selection to prevent post-operative instability

Dr. Sanjay Agarwala, Department of Orthopaedics, P D Hinduja Hospital and Medical Research Centre, Veer Savarkar Marg, Mahim (West), Mumbai - 400016, Maharashtra, India. E-mail: drsa2011@gmail.com

Introduction: Prosthetic instability remains a major challenge in total hip replacement (THR), which can result in dislocation, reduced mobility, and prosthetic loosening, requiring revision surgery. The forced drop leg test (FDLT) introduces a proactive approach by assessing hip stability under forced flexion, adduction, and rotation mimicking real-world dislocation mechanisms.

Technique: Standard exposure and trial implants are utilized to evaluate fit and alignment. With the trial components in place, the leg is abducted to 30–40°, then forcefully dropped into a sterile pouch in front. The hip joint is subsequently examined for dislocation or subluxation. In case of any dislocation or subluxation, reassessment of the component size and position is necessary.

Conclusion: Preliminary evidence suggests that FDLT enhances existing stability checks, although broader clinical validation and protocol standardization are necessary to confirm its effectiveness.

Keywords: Total hip replacement, intraoperative stability, hip dislocation, forced drop leg test.

Total hip replacement (THR) success hinges on the intraoperative stability of the artificial hip. The post-operative dislocation rates range from <1% to 22% [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8], with most occurring within 3 months [9,10,11,12]. Posterior dislocation, often triggered by forced flexion-adduction-rotation, dominates these cases. Current stability tests fail to replicate the dynamic forces behind dislocations, highlighting the need for innovations such as the forced drop leg test (FDLT). By rigorously evaluating high-risk positions, FDLT can help ensure prosthetic stability.

- Hip exposure and implant placement

Standard exposure and trial implants are utilized to evaluate fit and alignment.

Stability tests are done to look for potential impingement. The acetabular component may be fixed during this phase of surgery. Trial femoral head and stem are used before final fixation.

- Leg positioning

The surgeon meticulously ensures that the femoral head moves freely within the acetabulum without undue restriction from the surrounding soft tissues. A comprehensive assessment of impingement-free range of motion (ROM) is conducted across all planes of movement.

- FDLT:

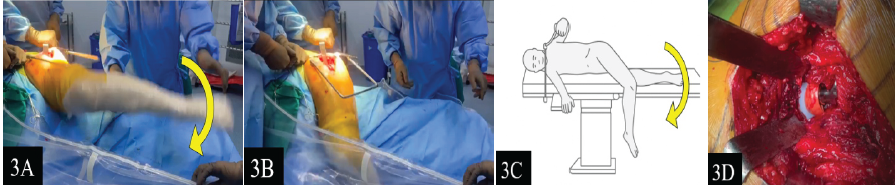

From the starting neutral position of the leg (Fig. 1), abduct the leg to 30–40° (Fig. 2), then forcefully drop it into a sterile pouch in front (Fig. 3). The hip joint is subsequently examined for signs of dislocation or subluxation. The FDLT test should be performed with controlled force and under direct visualization to avoid undue excessive stress on periarticular soft tissues or implant interfaces.

Figure 1: Starting position of leg while performing forced drop leg test. (a) Clinical photograph from the foot-end perspective. (b) Clinical photograph from the front view. (c) Diagrammatic illustration corresponding to (b).

Figure 2: 30–40° abduction position of the leg. (a) Clinical photograph viewed from the foot-end. (b) Clinical photograph from the front view. (c) Diagrammatic illustration corresponding to (b).

Figure 3: Forceful drop and confirmation of hip stability. (a) Clinical photograph showing the leg in the act of forceful dropping from the abducted position. (b) Clinical photograph showing the position of the leg at the end of the forced drop leg test. (c) Diagrammatic illustration corresponding to (b). (d) Clinical photograph confirming a stable, Undisplaced hip joint following the forceful drop manoeuvre.

Dislocation during this maneuver prompts a reassessment of the component size and position. This technique specifically evaluates hip stability under conditions of forceful flexion, adduction, and rotation, providing valuable insights into the joint’s resilience against dislocation force.

- Adjustments and confirmation:

If instability is identified, adjustments are made to the positioning and/or size of the components. The test is then repeated to ensure adequate stability before proceeding with the final fixation of the implants.

Prosthetic dislocation is a common and debilitating complication of THR. This often stems from inadequate intraoperative testing of high-risk movements. While traditional impingement and ROM tests are useful, they lack the dynamic force and movement replication of real-life dislocation scenarios [13,14]. FDLT bridges this gap by simulating these forces and offering actionable feedback on implant alignment and soft tissue balance. The FDLT is most easily performed through posterior and lateral approaches, where adequate visualization and mobility are achievable. Its application in anterior or minimally invasive approaches may be limited, and modifications to adapt the maneuver in these settings should be explored in future studies.

The advantages of FDLT include that it provides immediate feedback on component position, size, and soft-tissue tension. This allows a surgeon to make required adjustments to component selection and alignment before final implantation, thereby reducing the risk of post-operative instability.

Despite its promise, the FDLT has limitations that warrant further investigation. The technique’s efficacy and reproducibility need to be validated through larger clinical studies. As this is being introduced as a novel intraoperative technique, long-term prospective trials will be carried out in due course to evaluate its impact on post-operative dislocation rates and long-term functional outcomes. Standardization of the FDLT protocol, including specific thresholds for identifying instability, is required to ensure consistent outcomes. Like many intraoperative stability tests, the degree of force during the FDLT is based on the surgeon’s clinical judgment and experience. While this introduces some variability, it allows for patient-specific assessment. In addition, the learning curve associated with FDLT may vary among surgeons, necessitating adequate training and familiarity with the technique. The outcome of the FDLT may vary depending on the surgeon’s interpretation. However, with increasing familiarity and structured training, inter-surgeon variability can be minimized, improving the test’s reproducibility and reliability.

The broader implications of FDLT extend beyond its immediate application in THR. By enhancing intraoperative evaluation methods, the FDLT may contribute to a paradigm shift in the way surgeons approach prosthetic joint stability. Its adoption could lead to improved patient outcomes and reduced rates of dislocation and revision surgeries, thereby lowering healthcare costs associated with complications.

The use of FDLT ensures intraoperative stability assessment in THR, putting the surgeon’s mind at ease that even the most extreme and sudden movements will not result in prosthetic dislocation. FDLT provides immediate feedback on soft-tissue balance and implant alignment, thus enhancing surgical precision. Although the early results are encouraging, further research is essential to validate its reliability, refine the protocols, and establish its routine use in THR procedures.

The FDLT is a valuable intraoperative tool for assessing hip stability during THR. By replicating the forces associated with dislocation, the FDLT provides dynamic feedback that guides the adjustment of implant positioning and component selection. This technique has the potential to empower surgeons to pre-empt instability, thus preventing dreaded complications and improving patient outcomes.

References

- 1. National Joint Registry for England, Wales, Northern Ireland and the Isle of Man. 15th Annual Report. Hemel Hempstead: NJR Centre; 2018. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 2. Berry DJ, Von Knoch M, Schleck CD, Harmsen WS. Effect of femoral head diameter and operative approach on risk of dislocation after primary total hip arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2005;87:2456-63. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 3. Parvizi J, Picinic E, Sharkey PF. Revision total hip arthroplasty for instability: Surgical techniques and principles. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2008;90:1134-42. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 4. Meek RM, Allan DB, McPhillips G, Kerr L, Howie CR. Late dislocation after total hip arthroplasty. Clin Med Res 2008;6:17-23. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 5. Bozic KJ, Kurtz SM, Lau E, Ong K, Vail TP, Berry DJ. The epidemiology of revision total hip arthroplasty in the United States. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2009;91:128-33. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 6. Gwam CU, Mistry JB, Mohamed NS, Thomas M, Bigart KC, Mont MA, et al. Current epidemiology of revision total hip arthroplasty in the United States: National inpatient sample 2009 to 2013. J Arthroplasty 2017;32:2088-92. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 7. Bozic KJ, Kamath AF, Ong K, Lau E, Kurtz S, Chan V, et al. Comparative epidemiology of revision arthroplasty: Failed THA poses greater clinical and economic burdens than failed TKA. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2015;473:2131-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 8. Kunutsor SK, Barrett MC, Beswick AD, Judge A, Blom AW, Wylde V, et al. Risk factors for dislocation after primary total hip replacement: Meta-analysis of 125 studies involving approximately five million hip replacements. Lancet Rheumatol 2019;1:e111-21. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 9. Woo RY, Morrey BF. Dislocations after total hip arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1982;64:1295-306. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 10. Fessy MH, Putman S, Viste A, Isida R, Ramdane N, Ferreira A, et al. What are the risk factors for dislocation in primary total hip arthroplasty? A multicenter case-control study of 128 unstable and 438 stable hips. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res 2017;103:663-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 11. Tamaki T, Oinuma K, Miura Y, Higashi H, Kaneyama R, Shiratsuchi H. Epidemiology of dislocation following direct anterior total hip arthroplasty: A minimum 5-year follow-up study. J Arthroplasty 2016;31:2886-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 12. Berlinberg EJ, Burnett RA, Rao S, Serino J, Forlenza EM, Nam D. Early prosthetic hip dislocation: Does the timing of the dislocation matter? J Arthroplasty 2024;39:S259-65.e2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 13. Brush PL, Santana A, Toci GR, Slotkin E, Solomon M, Jones T, et al. Surgeon estimations of acetabular cup orientation using intraoperative fluoroscopic imagining are unreliable. Arthroplast Today 2023;20:101109. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 14. Tanino H, Sato T, Nishida Y, Mitsutake R, Ito H. Hip stability after total hip arthroplasty predicted by intraoperative stability test and range of motion: A cross-sectional study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2018;19:373. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]