This is the description of a surgical technique to spare the subtalar joint of the patient, with distal tibia bone defect.

Dr. Tribak Karim, Departement of Orthopaedic Surgery, Cliniques Universitaires Saint-Luc, Brussels, Belgium. E-mail: karim.tribak@saintluc.uclouvain.be

Introduction: The difficulties of managing bone loss in the distal tibia are well known in the literature. The various therapeutic options available to us include custom prosthetic replacement, talocrural arthrodesis with allograft, vascularized or non-vascularized autograft, bone transfer according to Ilizarov and insertion of a metal augment. In the case of non-conservation of the talocrural joint, osteosynthesis is performed using adapted plates and screws or, more conventionally, transplanted centromedullary nailing. We report on a clinical case of bone loss in the distal tibia in an infectious context, using an innovating talocrural arthrodesis reconstruction technique with allograft insertion at the level of the bone defect. Fixation was achieved with an anterograde tibiotalar nailing, which enabled preservation of the subtalar joint and compliance with the biomechanical principles of stable fixation.

Case Report: We report the clinical case of a 40-year-old patient with osteitis of the distal tibia following open trauma which required multiple surgeries of the osteosynthesis and cover flap type. The uncontrolled infection and skin fistulation led to a two-stage operation. The first stage consisted of resection of 9 cm of infarcted distal tibia, bacteriological samples were also taken, a cement spacer was inserted, temporary fixation was provided by an external fixator, and appropriate antibiotic therapy was administered for a period of 3 months. The second stage of the operation took place 6 weeks after the first and consisted of reconstruction using an intercalary distal tibial allograft and stabilization using an anterograde tibiotalar centromedullary nailing with stable static fixation. Demineralized bone matrix (DBM) was placed at the native bone-allograft junction. The patient’s fellow-up is 9 years, the complete bypass has been achieved with consolidation, the subtalar joint is preserved, and the viability of the construct is maintained.

Conclusion: Anterograde tibiotalar centromedullary nailing is a stable and reliable method of fixation in the management of distal tibial bone defects with talocrural arthrodesis.

Keywords: Distal tibial bone defect, infection, allograft, anterograde intramedullary nailing.

The management of distal tibia bone defects in an infectious context remains very challenging in our practice. Depending on the extent of bone loss in a septic setting, amputation may be unavoidable. Amputation is generally very poorly perceived by both the patient and the surgeon [1]. The superiority of bone defect reconstruction over amputation has been demonstrated in certain cases [2]. In the case of bone defects of the distal tibia in a septic context, reconstruction can be ensured by tibiotalocalcaneal arthrodesis [3]. Filling is carried out using a metallic implant or by allograft or autograft. Fixation is usually achieved with a transplantar intramedullary nail [3]. Depending on the extent of the bone defect, the biomechanical stability of the transplantar intramedullary nailing may be compromised in terms of load distribution. This technique also condemns the subtalar joint and exposes it to infectious contamination. We report a case of infection of the distal tibia which led to a wide resection of 9 cm with the insertion of a cement spacer polymethyl methacrylate (PMC) and an external fixator. The second stage took place 6 weeks later with reconstruction using a massive allograft and conventional anterograde tibial intramedullary nailing to ensure tibiotalar arthrodesis with DBM interposition at the host-allograft junction zones. The subtalar joint was spared and the fundamental principles of stable fixation were respected. This is the first case in the literature to report this method of fixation of a talocrural arthrodesis in the context of the management of a major bone defect of the distal tibia of infectious origin.

A 40-year-old patient with antecedent of open trauma to the lower extremity of the left tibia. It was a work accident on the second April 2014. The initial treatment, in another hospital, consisted of an external fixation, and 18 days later, an open reduction and internal fixation were performed. An infection of the fracture site occurred with skin necrosis. This situation led to removal of the material on the distal tibia, the fibular plate was left inside and skin coverage with a serratus free flap and external fixation. The antibiotic therapy was continue. A long time after this episode, in August 2015, the patient presented to the emergency room of our establishment with local inflammatory symptoms (Fig. 1) skin fistulation with purulent discharge, pain, and functional impotence of the left lower limb.

Figure 1: Clinical appearance on admission of the patient to the emergency room.

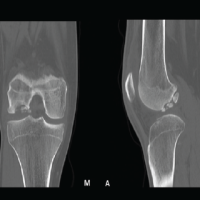

Radiological assessment (radiograph, computed tomography-scan, and magnetic resonance imaging) showed osteitis of the distal tibia over an area of 9 cm (Figs. 2 and 3).

Figure 2: X-ray on admission showing osteitis of the distal tibia.

Figure 3: Pre-operative computed tomography scan showing the extent of osteitis in the distal tibia over 9 cm.

The patient was managed surgically with lifting of the covering flap using a lateral surgical approach, removal of the material from the lateral malleolus, osteotomy of the fibula, resection of 9 cm of distal tibia involving the metaphysis and the epiphysis, intramedullary curettage of the tibia at the section area, filling with a cement PMC and Hoffman-type external fixation (Fig. 4).

Figure 4: Bone distal tibia resection, external fixator and filling with polymethyl methacrylate.

Bacteriology revealed a staphylococcus aureus and appropriate antibiotic therapy was administered first intravenously (Vancomycin) for 15 days and then orally (Bactrim Forte and Rifadine) until the second surgery.

Six weeks after the first surgery, we proceeded with the second surgical step, which consisted of repeating the same lateral approach, lifting the covering flap, removing the cement spacer while respecting the induced membrane, curettage and removal of tissue from the proximal tibial medullary shaft, complete removal of the cartilaginous surface of the talus, and placement of a massive 9 cm distal tibial allograft at the defect. To respect the principles of osteoconduction and interfragmentary contact between the allograft and the native bone, a step cut was made at the junction between the distal native tibia and the allograft. The distal part of the tibial allograft was also petalized before being anchored in the cancellous bone of the talus.

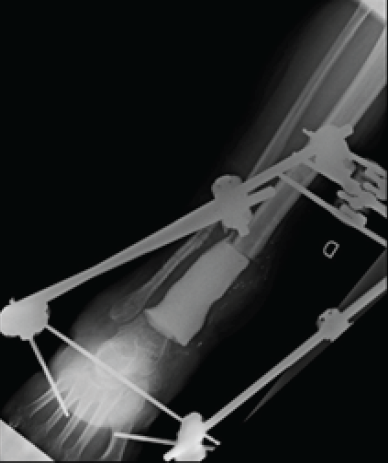

We opted for an anterograde tibiotalar intramedullary nailing with a conventional tibial nail, ensuring tibiotalar arthrodesis with stable static fixation at proximal tibial and talar level (Fig. 5).

Figure 5: Post-operative X-ray, distal tibia allograft, and anterograde tibia–talus intramedullary nailing

The subtalar joint was spared to avoid possible contamination and also to preserve continuity of load absorption at this level. A mixture of bone marrow taken from the patient’s iliac crest and demineralized bone matrix (DBM) was placed in the proximal and distal junction zones, host-graft junctions, to ensure osteoinduction. Strict absence of weight-bearing was maintained for a period of 3 months with thromboprophylaxis by daily low-molecular-weight heparin. Vitamin C was also administered during this period.

Antibiotic therapy was continued for a further 6 weeks postoperatively (Bactrim Forte and Rifadine), because the identified germ was staphylococcus aureus which has high virulence rate and also because the reconstruction of the defect was performed by allograft and intramedullary nail type osteosynthesis material. The patient was followed up in consultation on a regular basis with biological, radiological, and clinical monitoring. The follow-up was marked by a very good clinical evolution with complete healing of the surgical wound, improvement and normalization of the various parameters of the patient’s blood pressure, and normalization of the various parameters of the blood test. Several radiographic and scanographic controls were carried out and showed the appearance of filling and bridging tissues with very good progress. The callus first appeared at the proximal junction of the allograft and the native bone (Fig. 6). Subsequently, filling tissue gradually appeared at the distal level, with a different rate of appearance. The process of filling and bridging at the two junctions continued on its own over the years.

Figure 6: Computed tomography scan showing the callus appearance in a proximal junction first.

Resection of the infection, appropriate antibiotic therapy over a sufficient period of time, and the stability of the reconstruction have enabled the patient to gradually gain in comfort and autonomy. The current fellow-up is 9 years (Fig. 7).

Figure 7: Post-operative X-ray at 9 years fellow-up.

Reconstruction of bone defects in the distal tibia remains a challenge, with multiple difficulties in terms of skin coverage, filling, and respect for the tibiotalar joint. For a long time, transtibial amputation was the reference treatment for these bone defects, and the results reported in the literature were satisfactory [2]. Today, amputation is clearly less accepted by the majority of patients. A large number of techniques and therapeutic options for reconstructing bone defects in the distal tibia have been developed, with no proven superiority of one technique over another [4]. The best reconstruction should provide good osteoconduction and osteoinduction combined with good biomechanical stability with a minimum of complications. Filling with tantalum augments ensures early functional restoration, but the risk of sepsis and loosening is not negligible, and may lead to amputation, which is considered a failure by both the patient and the surgeon. Allografts are also used to fill bone defects, and the availability of this material can be difficult depending on the center [5], but we have not encountered this difficulty. The use of allografts is not without complications, namely, fractures (12–20%), pseudarthrosis (11–17%), malunion (12–15%), and infections [6]. Autografting is indicated for medium-sized bone defects of around 4–5 cm. Autografting through the fibula has been reported in the literature to give good results with a healing rate of 83%. Centralization of the fibula has also been described with good results [7].

For large bone defects, a vascularized autograft can also be performed and is widely used in the literature [8], but it remains a technique that requires a certain learning curve and requires an experienced team with this type of surgery and the donor site could be the site of a certain morbidity. It should also be noted that fixation will be provided either by plate or external fixation. Tibial bone distraction according to Ilizarov is an effective and proven procedure [9]. The Ilizarov bone transfer technique is a stable assembly on three planes of space. This procedure does not require a bone graft and reduces the risk of vascular damage associated with conventional surgery [10]. Furthermore, this technique has certain drawbacks, notably the relatively long duration of treatment compared to patient tolerance, it’s also need numerous X-ray control and radiation exposure. The duration of treatment depends on the size of the defect; in our case, the defect was 9 cm, knowing that the elongation is 1 mm per day. There are other disadvantages to this technique, namely, soft-tissue incarceration, loosening of the pins, and a potentially significant risk of infection [10]. There may also be a loss of osteogenic activity in the bone tissue at the extremity of the bone defect after prolonged traction (X). Circular external fixation in this context of bone transfer is far superior to lateral external fixation [9], but, in this case, the external fixator must be kept in place for a long time, with the risk of infection. Given that the loss of bone substance involved the tibiotalar joint, we did not consider this technique. There is also the concept of bone distraction according to Ilizarov using an external fixator and an additional intramedullary nail for guidance. This option was not retained either, given the extent of the bone defect and its topography involving the distal talocrural joint line. Each reconstruction technique has its advantages and disadvantages. In our clinical case, the defect was 9 cm in the distal tibia. Filling with an autograft or augmentation with Dentalium was not possible given the extent of the bone loss. We, therefore, opted for a custom-cut distal tibia allograft and prepared the proximal side with a cut step to ensure good primary stability. Distally, the allograft was petaled and then overlapped in the cancellous bone of the talus. Given that the defect involved the tibiotalar joint, a tibiotalar arthrodesis was inevitable. The fixation by a tibiotalocalcaneal arthrodesis by transplantar nail gives good stability [2,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11]. In our clinical case, we wanted to preserve the subtalar joint from any possible infection. Apart from ordering a custom-made transplant nail of the appropriate length, no transplant implant was of sufficient length to ensure a good lever arm and good biomechanical load distribution. All commercially available transplant implants were short with maximum 30 cm length. We opted for allograft filling and stabilization using an anterograde tibial nail of sufficient length to bridge the talus and ensure talocrural arthrodesis, with stable static screw fixation. The reaming – irrigation – aspiration procedure was interesting insofar as it preserves the bone capital [12], but we have not used this procedure. The length of the centromedullary nailing was two-thirds of the length of the distal tibial bone defect, and the principle of a sufficient lever arm was fully respected by this technique. The bone marrow associated with the DBM was placed at the junctions to ensure good osteoinduction. The appearance of bone callus first appeared after 17 months, at the proximal junction, where axial compression was maximal, followed by the appearance of callus at the distal junction. This situation had never compromised the stability of the construct and had always been clinically tolerable. The same observation was made by Xu et al., [13] who described the appearance of callus at the proximal junction after 26.5 months, with a mean bone defect of 14.2 cm (range, 11–18 cm). Xu et al., [13] also described the combination of a plate at the proximal junction of the allograft with screw fixation on either side of the transplantar nail, to increase stability at this level. We did not use this procedure in our case. In the series by Zhao et al. [14], in which the distal tibial defect averaged 12.7 cm ± 4.0 cm and was filled by a contralateral fibular autograft and fixation with a medial tibiotalar plate, the time to consolidation at the proximal and distal junctions was 10.5 ± 1.6 months and 8.7 ± 2.3 months, respectively. Subsequently, callus filling also occurred at the proximal and distal junctions and continued to develop at both junctions over several years. Compliance with the concept of a sufficient lever arm would appear to be essential in the fixation of bone defects filled by allograft.

The management of major bone defects of the distal tibia involving the joint space, in a septic context, must comply with specifications ensuring maximum stability of the filling material. Intramedullary nailing is a very stable fixation procedure in this case, which provided that a sufficient lever arm is used in relation to the extent of the bone loss. Stabilization using an anterograde tibial nail, which ensures tibiotalar arthrodesis while sparing the subtalar joint, seems to us to be a reliable and effective procedure in the management of large distal tibial bone loss in a septic context. This technique enabled the patient to achieve consolidation of his allograft and avoid amputation.

Tibiotalar arthrodesis using anterograde tibia nail in septic context with distal tibial bone defect represents an innovating and stable procedure, preserving the sub-talar joint and leading to healing.

References

- 1. Laitinen M, Hardes J, Ahrens H, Gebert C, Leidinger B, Langer M, et al. Treatment of primary malignant bone tumours of the distal tibia. Int Orthop 2005;29:255-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 2. Mavrogenis AF, Abati CN, Romagnoli C, Ruggieri P. Similar survival but better function for patients after limb salvage versus amputation for distal tibia osteosarcoma. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2012;470:1735-48. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 3. Ochman S, Evers J, Raschke MJ, Vordemvenne T. Retrograde nail for tibiotalocalcaneal arthrodesis as a limb salvage procedure for open distal tibia and talus fractures with severe bone loss. J Foot Ankle Surg 2012;51:675-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 4. Kunz P, Bernd L. Methods of biological reconstruction for bone sarcoma: Indications and limits. Recent Results Cancer Res 2009;179:113-40. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 5. Delloye C, Cornu O, Druez V, Barbier O. Bone allografts: What they can offer and what they cannot. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2007;89:574-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 6. Thompson RC Jr., Garg A, Clohisy DR, Cheng EY. Fractures in large – segment allografts. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2000;370:227-35. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 7. Puri A, Subin BS, Agarwal MG. Fibular centralisation for the reconstruction of defects of the tibial diaphysis and distal metaphysis after excision of bone tumours. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2009;91:234-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 8. Campanacci DA, Scoccianti G, Beltrami G, Mugnaini M, Capanna R. Ankle arthrodesis with bone graft after distal tibia resection for bone tumors. Foot Ankle Int 2008;29:1031-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 9. Song X, Shao X. Effect of annular external fixator-assisted bone transport on clinical healing, pain stress and joint function of traumatic massive bone defect of Tibia. Comput Math Methods Med 2022;2022:9052770. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 10. Cao Z, Zhang Y, Lipa K, Qing L, Wu P, Tang J. Ilizarov bone transfer for treatment of large tibial bone defects: Clinical results and management of complications. J Pers Med 2022;12:1774. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 11. Dieckmann R, Ahrens H, Streitburger A, Budny TB, Henrichs MP, Vieth V, et al. Reconstruction after wide resection of the entire distal fibula in malignant bone tumours. Int Orthop 2011;35:87-92. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 12. O’Malley NT, Kates SL. Advances on the Masquelet technique using a cage and nail construct. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2012;132:245-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 13. Xu L, Zhou J, Wang Z, Xiong J, Qiu Y, Wang S. Reconstruction of bone defect with allograft and retrograde intramedullary nail for distal tibia osteosarcoma. Foot Ankle Surg 2018;2:149-53. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 14. Zhao Z, Yan T, Tang X, Guo W, Yang R, Tang S. Novel “double-strut” fibula ankle arthrodesis for large tumor-related bone defect of distal tibia. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2019;20:367. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]