Initiating antitubercular therapy should follow established national guidelines, especially in an endemic country like India.

Dr. Abhinav Singla, Department of Orthopaedics, Government Medical College and Hospital, House No. 1206, Gmch Campus, Sector 32B, Chandigarh - 160030, India. E-mail: docabsingla@gmail.com

Introduction: Pediatric osteoarticular infections often present diagnostic challenges, especially in regions endemic to tuberculosis (TB). Misinterpretation of imaging findings may lead to inappropriate treatment, including the unwarranted use of anti-tubercular therapy (ATT).

Case Report: We present the case of a 10-year-old child with chronic left ankle swelling and pain for over a year, initially diagnosed with tuberculous arthritis based on magnetic resonance imaging findings. Despite 2 months of ATT, symptoms persisted. Upon referral, further evaluation, including biopsy and culture, revealed a retained foreign body (thorn) within the ankle joint capsule and Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection. ATT was discontinued, and antibiotic therapy, as per culture sensitivity, was initiated, leading to complete clinical recovery.

Conclusion: This case underscores the importance of microbiological or histopathological confirmation before initiating ATT in osteoarticular infections. Reliance solely on imaging may lead to misdiagnosis, delayed appropriate treatment, and potential public health implications. Clinicians should maintain a high index of suspicion for alternative diagnoses, especially in atypical presentations or non-responders to ATT.

Keywords: Osteoarticular tuberculosis, antitubercular therapy, diagnosis, histopathology.

Osteoarticular infections in children present a diagnostic dilemma due to overlapping clinical and radiological features between tuberculous and non-tuberculous etiologies. In tuberculosis (TB)-endemic regions, the threshold for initiating empirical anti-tubercular therapy (ATT) is often low, particularly when imaging suggests possible TB. However, this approach may lead to diagnostic errors, delayed treatment of the actual condition, and unnecessary exposure to the adverse effects of ATT. The diagnosis of tuberculous arthritis requires a comprehensive approach that includes clinical assessment, imaging, and, crucially, microbiological or histopathological confirmation. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), while sensitive, lacks specificity and may mimic other pathologies such as foreign body reactions or pyogenic infections. In children, a history of trauma or foreign body insertion is often overlooked, leading to misdirected management strategies. We are reporting a rare and instructive case of a pediatric patient initially misdiagnosed with tuberculous ankle arthritis based on MRI findings. Further evaluation revealed a retained intra-articular thorn causing chronic synovitis and Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection. This case highlights the critical need for a thorough diagnostic workup before commencing ATT and reinforces the importance of considering alternative diagnoses in atypical cases. Although retrospective in nature, we want to emphasise that if the diagnosis is not clear after radiological investigations, the next step is to do a biopsy, which had not been done at any point in time in our case.

History

This 10-year-old patient presented with left ankle swelling and pain for 13 months. There was a history of trivial trauma while playing in a field before symptom onset. At initial presentation to a hospital near his place, X-rays were done, which were normal, and he was given painkillers and immobilisation for around 3 weeks. After which, he started walking full weight bearing, but he continued to have persistent pain. MRI was performed at another hospital after 9 months of symptom onset, which suggested the possibility of TB infection, and ATT was started empirically. No cultures or biopsies were done. This was the information that we got from the patient after going through his old records. The patient presented to our hospital after 2 months of being on ATT and no resolution of symptoms.

There was no history of fever or other constitutional symptoms such as loss of appetite, loss of weight, or night sweats, which are usually seen in tubercular infections.

On examination

The joint had visible swelling and was warm to the touch. There was localised tenderness on the anterolateral aspect of the ankle joint. The swelling was firm with no visible or dilated veins. The overlying skin was pinchable. The range of motion (mainly dorsiflexion) was restricted. The child walked with an antalgic gait. There was no regional lymphadenopathy. There was no fever or any other systemic findings.

Investigations

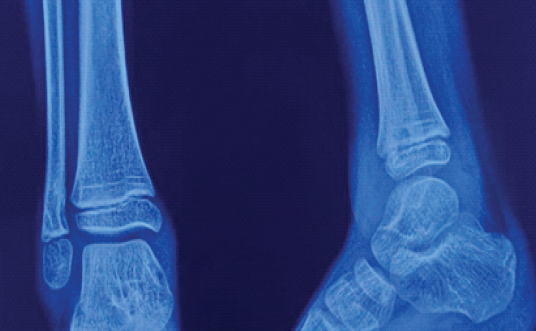

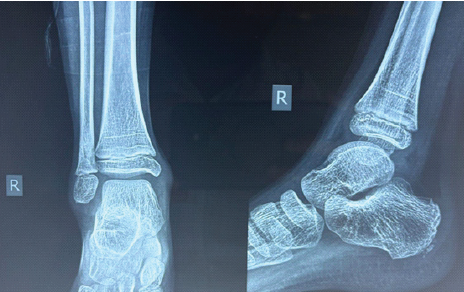

Plain radiographs of the ankle show a lytic lesion in the distal fibula just proximal to the physis (Fig. 2).

Figure 2: Plain radiograph of the ankle joint showing a lytic lesion at the anteromedial cortex of the distal fibula just proximal to the physis.

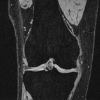

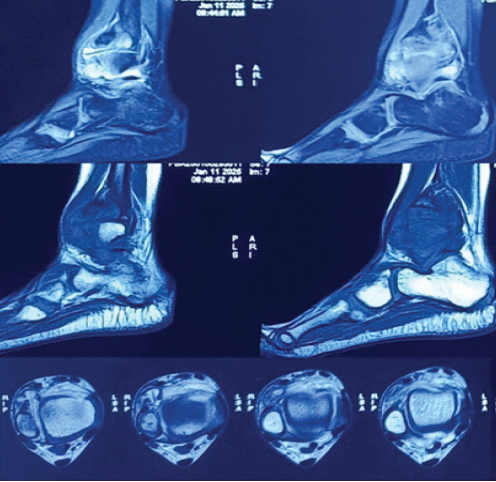

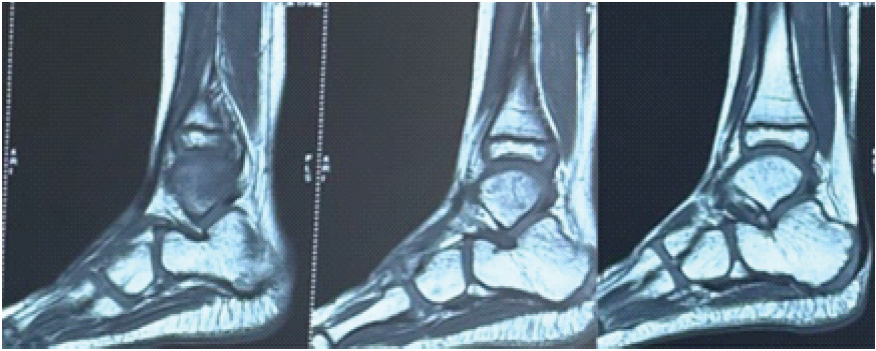

Review of MRI at our institute showed a T2 hyperintense lesion at the lower end of the fibula reaching up to the cortex medially with cortical irregularity. The lesion was surrounded by marrow oedema (Fig. 3). It was possible to see mild joint effusion, synovial effusion, and synovial hypertrophy. The diagnosis of TB was not definitive.

Figure 3: Sections of magnetic resonance imaging showing a foreign body just anterior to the syndesmosis and ankle joint effusion.

Management

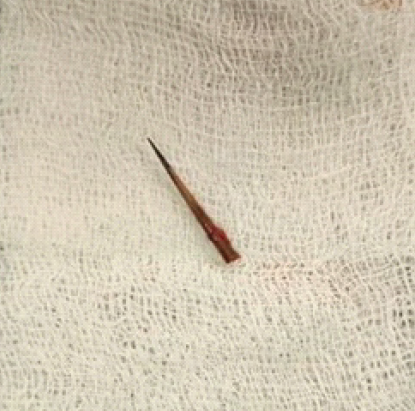

The patient was planned for needle biopsy proceeding to open biopsy if needed, and drainage. There was no frank pus during the procedure, but tissue yield was very less on needle biopsy, so the plan was changed to do an open biopsy. There was no collection found inside the joint except the hypertrophied synovial tissue. A foreign body, likely to be a thorn (Fig. 1), was found inside the joint capsule.

Figure 1: Clinical picture of a foreign body, likely a thorn, extracted from the ankle joint.

Bony biopsy, synovial biopsy samples sent for acid-fast bacilli (AFB) stain, tubercular cultures, and Cartridge-Based Nucleic Acid Amplification Test (CBNAAT) were all negative. The material that was sent for culture sensitivity grew P. aeruginosa. ATT was stopped. Culture-specific antibiotics for Pseudomonas were started. At present, around 10 months post-biopsy and drainage, he was walking without any pain and full weight bearing. X-rays at 10 months showed a healing lytic lesion of the fibula (Fig. 4). MRI showed resolution of synovitis: Joint effusion and marrow oedema (Fig. 5).

Figure 4: Plain radiograph of the ankle 10 months postoperatively showing the healing of a lytic lesion in the distal fibula.

Figure 5: Magnetic resonance imaging 10 months postoperatively showing resolved synovitis and no marrow edema.

Untreated retained foreign bodies in the pediatric population can have variable osteoarticular manifestations. Gupta et al. [1] reported a case where a neglected thorn injury presented as a soft tissue mass in the foot. D’Souza et al. [2] reported a case where a retained rubber foreign body mimicked midfoot osteomyelitis. Regmi et al. [3] reported a case where a thorn prick injury presented as osteomyelitis of the hand. Gupta et al. [4] reported two unusual cases highlighting how forgotten rubber or thread-based foreign bodies can closely mimic chronic osteomyelitis, leading to prolonged misdiagnosis. Kumar et al. [5] reported a case of retained plant thorn in the knee mimicking pigmented villonodular synovitis, leading to months of pain and a misleading radiographic picture. The case we are reporting presented to us as a misdiagnosed tubercular arthritis of the ankle. 15–20% of all TB cases worldwide are extrapulmonary TB (EPTB), with regional variations up to 24% in some places [6]. In India, EPTB comprises about 15–24% of TB cases and is more prevalent among human immunodeficiency virus-positive individuals, where incidence may exceed 50% [7]. About 10–15% of EPTB cases and 1–3% of all TB cases are osteoarticular TB (OATB), a kind of EPTB [8]. While spinal TB is most common, making up around 72% of OATB cases in India, extraspinal sites—including the ankle—account for the remainder [9]. Ankle TB is rare globally, forming <5% of OATB [8], but Indian studies have reported higher frequencies, with ankle involvement seen in 15.7–18.75% of extraspinal OATB cases [10,11]. These figures highlight the need for clinical vigilance, especially in endemic regions, where atypical presentations may delay diagnosis. In any child with chronic monoarticular swelling, TB is a key differential in endemic regions, but confirming the diagnosis is paramount. National guidelines (INDEX-TB) recommend obtaining microbiological and histopathological confirmation whenever possible before initiating therapy [12]. In practice, this means that aspiration of joint fluid or, preferably, a biopsy of synovium or bone should be performed for AFB smear, culture, histopathology, and molecular tests (e.g., GeneXpert) [13]. A thorough evaluation combining clinical assessment, imaging, and laboratory tests is needed because pediatric skeletal TB often has a slow, insidious presentation that overlaps with other musculoskeletal conditions [14]. Employing a multimodal diagnostic approach significantly improves accuracy and helps avoid misdiagnosis in pediatric osteoarticular infections [14]. MRI is a sensitive tool for detecting early musculoskeletal TB changes (e.g., synovial thickening, marrow edema, abscesses) and delineating the extent of disease [13]. Characteristic MRI features (such as lack of diffuse marrow enhancement, subligamentous abscesses, or “skip” lesions in vertebrae) can suggest TB over pyogenic infection [8]. However, MRI has limited specificity, as its findings can overlap with other chronic infections, malignancies, or inflammatory arthritis [15]. In our patient’s case, the MRI changes were misinterpreted as TB when the true pathology was a retained foreign body granuloma. This exemplifies how sole reliance on MRI can mislead; radiologic evidence must be corroborated with microbiological or histological proof before labeling a lesion as TB [15]. Histological examination of bone or synovial tissue remains a cornerstone of diagnosis. Finding caseating granulomas with Langhans giant cells on biopsy is highly suggestive of TB and is often considered confirmatory in the appropriate clinical context [16]. Histopathology is relatively sensitive for OATB, with a sensitivity of around 71.05% and a specificity of about 72.73%, although granulomatous inflammation can occur in other infections or chronic inflammatory conditions [17]. Thus, while typical histopathology strongly supports TB, microbiological confirmation is ideal. CBNAAT/GeneXpert rapidly detects Mycobacterium tuberculosis DNA and rifampicin resistance. GeneXpert shows high specificity (69.71%) and good sensitivity (89.47%) for OATB, providing quick confirmation and screening for rifampicin resistance [17]. Our patient’s negative GeneXpert result, consistent with negative culture and histology, permitted cessation of unnecessary treatment [18]. Although GeneXpert enhances diagnostic yield, it is not a replacement for culture or histopathology [18]. Culture is the gold standard, but positivity rates are around 53.52% due to the paucibacillary nature of the disease [17]. Obtaining a culture is strongly recommended despite its limited sensitivity [16] (Fig. 5). According to Agashe et al., initiating ATT is significant, and every effort must be made to rule out TB mimics before starting therapy [19]. Misdiagnosis exposes patients to months of potentially toxic drugs and delays correct treatment [19]. Both WHO and national guidelines emphasize confirming TB whenever possible [6,12]. The Indian INDEX-TB guidelines explicitly highlight the necessity of tissue sampling when diagnosis is uncertain [12]. At our hospital, adherence to these principles led to accurate diagnosis, whereas reliance solely on MRI at the previous treating center led to a diagnostic pitfall. Especially in children, who often do not manifest classic systemic TB signs, obtaining microbiological confirmation is crucial to avoid frequent misdiagnosis [14].

The initiation of ATT must be grounded in a rigorous diagnostic protocol incorporating clinical assessment, imaging, and crucially, microbiological or histopathological confirmation. Imaging alone, especially MRI, is insufficient for diagnosis due to its low specificity. Biopsy and microbiological tests remain the cornerstone for confirming OATB. Reckless or empirical ATT without adequate evidence risks misdiagnosis, delays in appropriate treatment, drug resistance, and avoidable toxicity. This approach aligns with the WHO recommendations and is essential for effective TB control and patient safety.

In TB-endemic areas, do not rely solely on imaging to diagnose OATB. Always confirm with biopsy or culture whenever in doubt to avoid misdiagnosis and inappropriate treatment.

References

- 1. Gupta M, Kumar D, Jain VK, Naik AK, Arya RK. Neglected thorn injury mimicking soft tissue mass in a child: A case report. J Clin Diagn Res 2015;9:RD03-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 2. D’Souza A, Chauhan N, Pathak A, Jeyaraman M. Retained rubber foreign body mimicking mid foot multi focal osteomyelitis – a case report. J Orthop Rep 2022;1:100032. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 3. Regmi M, Desai S, Patwardhan S, Deshmukh W, Kapoor T, Patil N. Foreign body induced osteomyelitis in the hand – commonly missed clinical and radiological diagnosis. J Orthop Case Rep 2021;11:80-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 4. Gupta A, Ghosh AK, Khatri J, Rangasamy K, Gopinathan NR, Sudesh P. Forgotten foreign bodies mimicking osteomyelitis, a diagnostic dilemma – a report of two cases. J Orthop Case Rep 2023;13:64-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 5. Kumar N, Singh DK, Hassan M, Rustagi A, Batta NS, Botchu R. Thorn-induced Injury of the knee mimicking pigmented villonodular synovitis (PVNS): A case report. Apollo Med 2024;21 1 suppl:S55-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 6. WHO. Global Tuberculosis Report. Geneva: WHO; 2024. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 7. Sharma SK, Mohan A. Extrapulmonary tuberculosis. Indian J Med Res 2004;120:316-53. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 8. Tuli SM. General principles of osteoarticular tuberculosis. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2002;398:11-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 9. Tuli SM. General principles of osteoarticular tuberculosis. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2002 May;(398):11-9. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200205000-00003. PMID: 11964626.. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

- 10. Dhillon MS, Goel A, Prabhakar S, Aggarwal S, Bachhal V. Tuberculosis of the elbow: A clinicoradiological analysis. Indian J Orthop 2012;46:200-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 11. Tuli SM. Tuberculosis of the Skeletal System. 4th ed. New Delhi: Jaypee Brothers; 2016. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 12. Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. INDEX-TB Guidelines. New Delhi: MoHFW; 2016. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 13. Leonard MK, Blumberg HM. Musculoskeletal Tuberculosis. Microbiol Spectr. 2017 Apr;5(2):10.1128/microbiolspec.tnmi7-0046-2017. doi: 10.1128/microbiolspec.TNMI7-0046-2017. PMID: 28409551; PMCID: PMC11687488. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

- 14. Herdea A, Marie H, Negrila IA, Abdel Hamid Ahmed AD, Ulici A. Reevaluating pediatric osteomyelitis with osteoarticular tuberculosis: Addressing diagnostic delays and improving treatment outcomes. Children (Basel) 2024;11:1279. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 15. Pattu R, Chellamuthu G, Sellappan K, Chendrayan K. Total elbow arthroplasty for active primary tuberculosis of the elbow: A curious case of misdiagnosis. Clin Shoulder Elb 2022;25:158-62. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 16. Chen SH, Lee CH, Wong T, Feng HS. Long-term retrospective analysis of surgical treatment for irretrievable tuberculosis of the ankle. Foot Ankle Int 2013;34:372-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 17. Singh D, Meena AK, Vahora N, Kumar R, Khanna G, Nair D, et al. CB-NAAT MTB/RIF assay and histopathology correlation in diagnosis of osteoarticular tuberculosis using culture as reference standard. J Clin Orthop Trauma 2019;10 Suppl 1:S53-6. Erratum in: J Clin Orthop Trauma 2020;11:1176. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 18. Nishal N, Arjun P, Arjun R, Ameer KA, Nair S, Mohan A. Diagnostic yield of CBNAAT in the diagnosis of extrapulmonary tuberculosis: A prospective observational study. Lung India 2022;39:443-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 19. Agashe VM, Rodrigues C, Soman R, Shetty A, Deshpande RB, Ajbani K, et al. Diagnosis and management of osteoarticular tuberculosis: A drastic change in mind set needed-it is not enough to simply diagnose TB. Indian J Orthop 2020;54 Suppl 1:60-70. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]