Three-stage revision with interim LRS external fixation provides a reliable limb-salvage solution for complex chronic periprosthetic knee infection.

Dr. V. Purushothaman, Department of Orthopaedics, Government Tirunelveli Medical College and Hospital, Tirunelveli, Tamil Nadu, India. E-mail: purushothaman.v4@gmail.com

Introduction: Chronic periprosthetic joint infection (PJI) following total knee arthroplasty (TKA) is a limb-threatening complication, especially in the presence of sinus tract formation, bone loss, and failed prior revisions. While two-stage revision remains the standard of care, its success is limited in complex infections.

Case Report: We present a single case of chronic infected TKA with a discharging sinus managed successfully using a three-stage revision protocol. The treatment involved implant removal and antibiotic-loaded cement spacer insertion, interim stabilization using a Limb Reconstruction System (LRS) external fixator, and definitive revision TKA.

Conclusion: The three-stage revision strategy with interim LRS fixation achieved complete infection eradication, restoration of limb alignment, and satisfactory functional outcome. This approach represents a reliable salvage option in complex chronic PJI cases.

Keywords: Periprosthetic joint infection, total knee arthroplasty, three-stage revision, limb reconstruction system fixator.

Periprosthetic joint infection (PJI) is one of the most devastating complications following total knee arthroplasty (TKA), with an incidence of 1–2% after primary TKA and up to 5% following revision procedures [1]. Two-stage revision arthroplasty remains the gold standard for chronic PJI with reported success rates of 80–90% [2]. However, failure rates are higher in complex infections characterized by sinus tract formation, bone loss, resistant organisms, and multiple prior surgeries [3,4].

Recent literature has emphasized that in such high-risk scenarios, conventional two-stage exchange may be insufficient, and a planned three-stage revision strategy may improve infection eradication and optimize conditions for definitive reimplantation [5,6,7,8,9,10]. The use of interim external fixation allows maintenance of limb alignment while avoiding internal hardware during infection control [11,12]. The diagnosis of chronic periprosthetic joint infection in this case was established based on the Musculoskeletal Infection Society criteria and subsequent consensus definitions. [5]

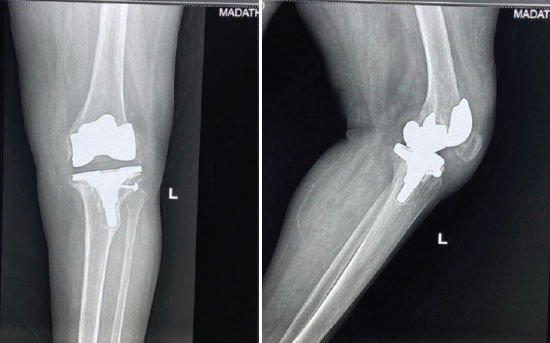

A 60-year-old female presented with pain, swelling, and a chronic discharging sinus over the anterior aspect of the left knee for 8 months following primary TKA performed elsewhere. She complained of difficulty in ambulation and recurrent episodes of fever. Clinical examination revealed a healed midline scar with an active sinus, valgus deformity of approximately 12°, and restricted knee movements (range: 10°–60°). Laboratory investigations showed elevated inflammatory markers (erythrocyte sedimentation rate [ESR]: 68 mm/h, C-reactive protein [CRP]: 42 mg/L). Plain radiographs (Fig. 1) demonstrated loosening of both femoral and tibial components with surrounding osteolysis. Joint aspiration and sinus tract culture grew methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus.

Figure 1: Weight-bearing radiographs showing loosening of both femoral and tibial components with surrounding osteolysis.

Stage I

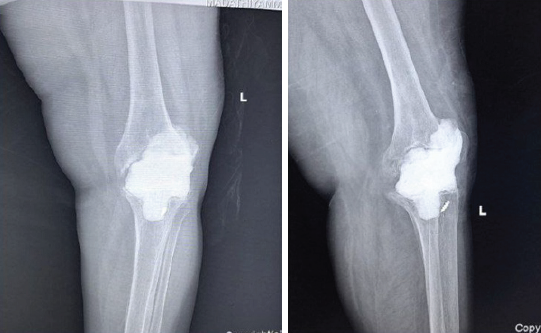

The patient underwent removal of all prosthetic components with radical debridement of infected and necrotic tissue. During tibial component removal, an iatrogenic quadriceps tendon avulsion occurred and was repaired using non-metallic suture anchors, restoring extensor mechanism continuity [13,14,15,16]. Following tendon repair, a hand-moulded antibiotic-loaded cement spacer containing vancomycin and gentamicin was inserted [6] (Fig. 2). Postoperatively, culture-directed intravenous antibiotics were administered for 3 weeks, followed by 3 weeks of oral antibiotics, completing a total antibiotic duration of 6 weeks after Stage I.The duration and sequencing of intravenous followed by oral antibiotic therapy were guided by established antimicrobial treatment principles for implant-associated infections. [13]

Figure 2: Post-operative anteroposterior and lateral radiographs following placement of an antibiotic-impregnated cement spacer after complete implant removal.

Stage II

After completion of 6 weeks of antibiotic therapy and a planned 3-week infection surveillance period, Stage II was undertaken. Although ESR and CRP had normalized, definitive reimplantation was deliberately deferred due to the presence of a chronic sinus tract, compromised soft-tissue envelope, and significant bone loss, placing the patient at a high risk of reinfection with immediate reimplantation.

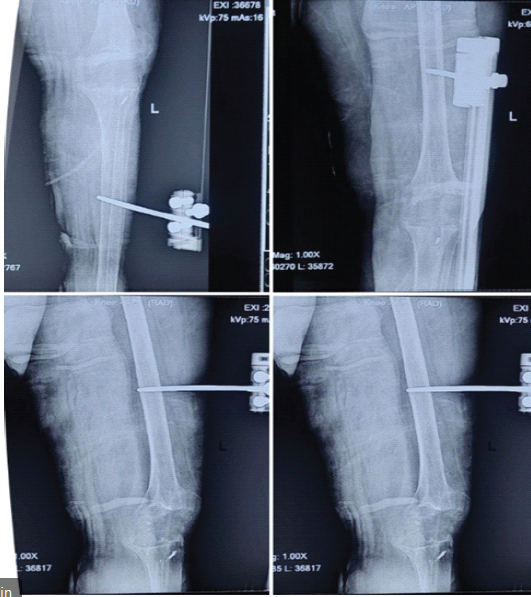

A limb reconstruction system (LRS) external fixator was applied to maintain limb length and alignment while avoiding the introduction of internal hardware that could serve as a nidus for persistent infection (Fig. 3).

Figure 3: Anteroposterior and lateral radiographs following the antibiotic cement spacer exit and fixation with the limb reconstruction system external fixator, maintaining joint alignment and limb length.

During this stage, the patient received an additional 3 weeks of culture-directed oral antibiotics. Partial weight bearing was permitted, and the patient was monitored clinically and biochemically for signs of recurrent infection.

The interval between Stage II and Stage III was 3 weeks. The total duration of six weeks of systemic antibiotic therapy following implant removal is consistent with recommendations for staged revision in prosthetic joint infection. [14]

Stage III

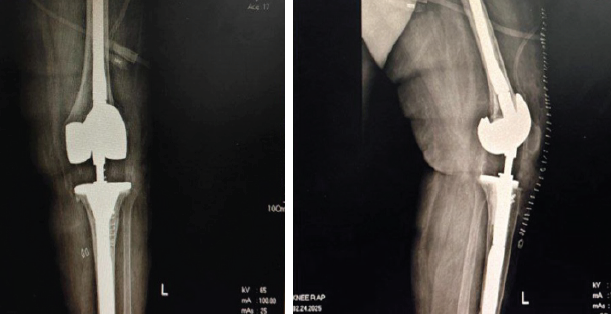

Following confirmation of infection eradication, definitive revision TKA was performed using a rotating hinge knee prosthesis (Fig. 4) due to ligamentous insufficiency and bone loss.

Figure 4: Immediate post-operative anteroposterior and lateral radiographs following revision total knee arthroplasty showing well-aligned and stable prosthetic components.

Rotating hinge knee prostheses have been shown to provide reliable stability and acceptable functional outcomes in complex revision total knee arthroplasty with severe ligamentous insufficiency. [17] Intraoperative cultures were sterile. Post-operative rehabilitation focused on gradual range-of-motion exercises and strengthening (Fig. 5). The Knee Society Score improved from 40 preoperatively to 86 postoperatively. Radiographs demonstrated stable implant fixation and satisfactory mechanical alignment. At the final follow-up of 20 months, the patient was pain-free, ambulating independently, and showed no evidence of recurrent infection.

Figure 5: Clinical photograph at final follow-up showing a healed surgical scar with satisfactory knee range of motion and absence of signs of infection.

PJI following TKA represents one of the most complex and resource‑intensive problems in contemporary orthopedic practice. Chronic PJI, in particular, is characterized by mature biofilm formation, sinus tract development, compromised host immunity, and poor local soft‑tissue environment, all of which significantly reduce the success of implant‑retaining procedures and single-stage revision strategies [3,4]. Two‑stage revision arthroplasty is widely regarded as the gold standard for chronic PJI, with reported infection eradication rates of 80–90% [2,6]. However, failure of two‑stage revision has been increasingly recognized in patients with resistant organisms, poor bone stock, ligamentous insufficiency, and those with multiple previous surgeries [7]. In such scenarios, reinfection risk remains substantial, often leading to repeated debridements, prolonged immobilization, or even limb-threatening situations. The three‑stage revision strategy was developed to address these high‑risk cases by introducing an additional interim phase that allows extended infection surveillance and biological recovery before definitive reimplantation [7]. Kildow et al. highlighted that three‑stage exchange arthroplasty may offer superior infection control in patients with sinus tracts, polymicrobial infections, and prior failed revisions, albeit at the cost of prolonged treatment duration [7]. In our case, the presence of a chronic sinus, component loosening, and bone loss made a conventional two‑stage revision less predictable. A key component of our protocol was the use of an LRS external fixator during the interim stage. Conventional static cement spacers, while effective for local antibiotic delivery, often fail to maintain limb alignment and may lead to stiffness, extensor mechanism shortening, and difficulty during reimplantation [6]. The LRS fixator provided stable mechanical alignment, preserved limb length, and allowed controlled partial weight bearing without introducing additional intramedullary or internal hardware that could serve as a nidus for persistent infection [8,9]. External fixation in the setting of infected arthroplasty has been described previously, particularly in cases with massive bone loss or instability. Tan et al. reported favorable outcomes using external fixation in complex periprosthetic knee infections, emphasizing its role in maintaining stability while minimizing reinfection risk [8]. Our experience aligns with these findings, as the LRS fixator facilitated soft‑tissue healing and optimized conditions for definitive reimplantation. Functional restoration remains an important endpoint in PJI management. Although the need for a rotating hinge knee prosthesis reflects the severity of bone and ligament loss, modern hinged designs have demonstrated acceptable mid‑ to long‑term outcomes in salvage situations [10,11]. In the present case, the patient achieved significant pain relief, stable ambulation, and meaningful improvement in Knee Society Score, underscoring that satisfactory function can still be achieved even in complex revision scenarios. Modern kinematic rotating hinge designs have demonstrated satisfactory mid- to long-term survivorship and functional outcomes in salvage revision knee arthroplasty. [18] Despite its success, the three‑stage approach is not without limitations. It requires prolonged treatment duration, multiple surgeries, increased cost, and strict patient compliance. However, when weighed against the morbidity of persistent infection, repeated failures, or amputation, the benefits may outweigh these disadvantages in carefully selected patients. This case reinforces the importance of individualized treatment planning in chronic PJI and supports the role of three‑stage revision with interim external fixation as a valuable salvage option when standard protocols are likely to fail.

Chronic PJI following TKA remains a formidable challenge, particularly in the presence of sinus tracts, bone loss, and failed prior interventions. This case demonstrates that a three‑stage revision strategy incorporating antibiotic‑loaded cement spacer, interim stabilization with an LRS external fixator, and definitive revision TKA can achieve reliable infection eradication and satisfactory functional recovery. The additional interim stage allows prolonged infection surveillance, optimization of the soft‑tissue envelope, and restoration of limb alignment before final reimplantation. The use of LRS external fixation provides mechanical stability without increasing the risk of reinfection and facilitates early mobilization, which is crucial for overall rehabilitation. While this approach involves multiple procedures and extended treatment duration, it should be considered a valuable limb‑salvage option in carefully selected high‑risk patients where conventional two‑stage revision may be insufficient. Larger studies with longer follow‑up are required to further define the role of three‑stage revision protocols; however, this case adds meaningful evidence supporting its use in complex chronic periprosthetic knee infections.

In chronic periprosthetic knee infections with sinus tract and bone loss, adding an interim stabilization stage using LRS external fixation can enhance infection control and improve functional outcomes before definitive revision TKA.

References

- 1. Kurtz SM, Lau E, Watson H, Schmier JK, Parvizi J. Economic burden of periprosthetic joint infection in the United States. J Arthroplasty 2012;27:61-5.e1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 2. Garvin KL, Hanssen AD. Infection after total knee arthroplasty: Past, present, and future. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1995;77:1576-88. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 3. Tsukayama DT, Goldberg VM, Kyle R. Diagnosis and management of infection after total knee arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1996;78:512-23. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 4. Zimmerli W, Trampuz A, Ochsner PE. Prosthetic-joint infections. N Engl J Med 2004;351:1645-54. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 5. Parvizi J, Zmistowski B, Berbari EF, Bauer TW, Springer BD, Valle CJ, et al. New definition for periprosthetic joint infection. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2011;469:2992-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 6. Masri BA, Duncan CP, Beauchamp CP. Long-term elution of antibiotics from bone cement. J Arthroplasty 1998;13:331-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 7. Kildow BJ, Della Valle CJ, Springer BD. Is two-stage exchange always sufficient for periprosthetic joint infection? J Arthroplasty 2020;35:S238-44. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 8. Tan TL, Shohat N, Rondon AJ, Foltz C, Goswami K, Ryan SP et al. Reimplantation timing and outcomes in chronic periprosthetic joint infection. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2021;103:558-68. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 9. Lichstein PM, Gehrke T, Parvizi J. Management of complex periprosthetic joint infection: When two stages may not be enough. Bone Joint J 2022;104-B:11-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 10. Ahmed SS, Haddad FS. Three-stage exchange arthroplasty for recalcitrant periprosthetic knee infection. EFORT Open Rev 2023;8:245-53. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 11. Corona PS, Vicente M. External fixation as an adjunct in infected total knee arthroplasty with bone loss. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2020;28:2765-73. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 12. Zahar A, Kendoff D, Gehrke T. Avoiding internal hardware during infection control in revision knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 2021;36:S291-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 13. Sendi P, Zimmerli W. Antimicrobial treatment concepts for orthopaedic implant-associated infections. Clin Microbiol Infect 2022;28:353-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 14. Aboltins CA, Page MA. Duration of antimicrobial therapy after staged revision for prosthetic joint infection. ANZ J Surg 2021;91:1763-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 15. Browne JA, Hanssen AD. Extensor mechanism complications following total knee arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2019;101:1681-92. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 16. Chalidis B, Petsatodis G, Papadopoulos P,Christoforidis J, Christodoulou A, Pournaras J. Suture anchor repair of quadriceps tendon rupture after total knee arthroplasty. Knee 2020;27:1189-95. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 17. Hsu RW, Hsu WH, Shen WJ. Use of hinged knee prosthesis in revision total knee arthroplasty. J Formos Med Assoc 2007;106:306-14. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 18. Springer BD, Hanssen AD, Sim FH, Lewallen DG. The kinematic rotating hinge prosthesis for complex knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2001;392:283-91. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]