Young patients with anatomically fixed acetabular fractures frequently develop femoral head avascular necrosis, and conversion total hip replacement using meticulous pre-operative planning, selective hardware removal, and careful sciatic nerve protection reliably restores a stable and functional hip.

Dr. M S Nirmal Rathi, Department of Orthopaedics, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Raipur, Chhattisgarh, India. Email: nirmalrathi7@gmail.com

Introduction: Traumatic avascular necrosis (AVN) of the femoral head is a major issue after acetabular fractures, affecting 20–40% of cases even with precise joint realignment. Performing total hip replacement (THR) as a salvage procedure introduces specific surgical obstacles absent in standard primary THR.

Case Report: This report covers a 26-year-old man injured in a motor vehicle collision with an acetabular fracture. After open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF), he had femoral head AVN with superior migration and absorption of superolateral acetabular rim at 18 months, requiring THR. Using a posterior surgical approach to hip, THR was performed by extracting unstable screws and placing cementless acetabular and femoral components. He had an unremarkable recovery, with notable improvements in pain and mobility.

Conclusion: Salvage THR after acetabular ORIF requires expertise, but thorough pre-operative strategy, targeted implants, and effective hardware removal deliver reliable success. Young adults with both-column injuries need ongoing AVN monitoring, regardless of initial perfect alignment.

Keywords: Acetabular injury, femoral head necrosis, salvage total hip replacement, both-column injury, traumatic joint degeneration.

Acetabular fractures occur primarily in young adults following high-energy trauma such as road traffic accidents, falls from height, and industrial injuries. Complex fracture patterns that involve both the anterior and posterior columns compromise the structural integrity of the acetabulum and threaten long-term hip function. Open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF) remains the preferred treatment for such injuries in young patients and aims to restore anatomical joint congruity, preserve the native hip, and delay or avoid arthroplasty. Despite advances in imaging, classification, and surgical technique, post-traumatic complications remain frequent. Post-traumatic osteoarthritis and femoral head avascular necrosis (AVN) develop in approximately 20–40% of patients after acetabular fracture fixation, especially in high-energy, multi-fragmentary patterns. Risk factors include initial cartilage damage, intra-articular debris, residual incongruity, and disruption of femoral-head blood supply. Once AVN or advanced post-traumatic degeneration produces pain, stiffness, and loss of function, conversion total hip replacement (THR) offers effective salvage. However, THR in this setting differs substantially from primary arthroplasty. Distorted bony anatomy, retained or loosened hardware, acetabular bone loss, and dense scar tissue increase the risk of component malposition, instability, neurovascular injury, and infection. Published series report higher complication rates and lower survivorship after conversion THR following acetabular fractures compared with primary THR, particularly with older implants and cemented acetabular components. Newer porous metal cups, enhanced screw fixation, and structured approaches to hardware removal and defect reconstruction have improved results. This case report describes a young adult who developed femoral head AVN and acetabular rim loss 18 months after anatomically performed ORIF for a both-column acetabular fracture and underwent successful conversion to uncemented THR. The report focuses on pre-operative planning, technical execution, and early functional outcome.

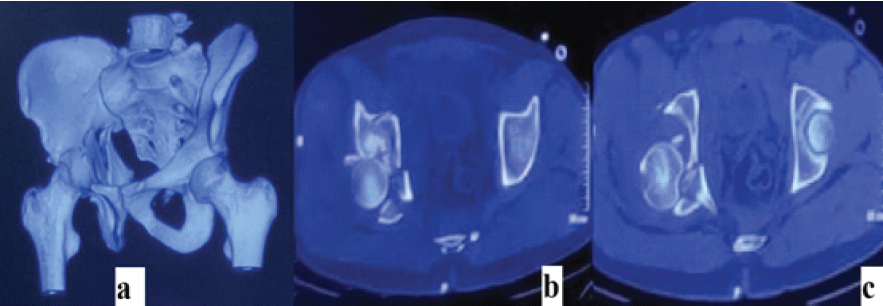

A 26-year-old male presented after a high-velocity road traffic accident with isolated left hip trauma. He was hemodynamically stable with no associated head, thoracoabdominal, or spinal injuries. The left lower limb appeared shortened and internally rotated, with severe hip pain and restricted active and passive motion. Distal pulses were palpable, and sensory and motor examination of the sciatic and femoral nerve distributions was normal. Anteroposterior pelvic radiographs (Fig. 1) and Judet views showed disruption of both the iliopectineal and ilioischial lines, indicating involvement of the anterior and posterior columns, with preservation of the obturator foramen, consistent with a both-column pattern. Computed tomography (CT) with three-dimensional reconstruction confirmed an anterior column posterior hemi-transverse acetabular fracture involving the weight-bearing dome and posterior wall (Fig. 2) according to the Letournel classification.

Figure 1: Anteroposterior radiograph of the pelvis at presentation showing disruption of the iliopectineal and ilioischial lines consistent with a both-column acetabular fracture, with the femur head subluxation.

Figure 2: Computed tomography of the pelvis at presentation – (a) three-dimensional reconstruction demonstrating a complex acetabular fracture involving both anterior and posterior columns; (b and c) axial computed tomography sections confirming fracture extension through the weight-bearing dome with involvement of the posterior wall.

Initial management

The patient underwent ORIF under general anesthesia using a Kocher-Langenbeck approach. After careful dissection and elevation of the short external rotators, the posterior column and wall fragments were identified, debrided, and reduced. Reduction clamps and traction were used to achieve anatomical restoration of joint congruity, guided by fluoroscopy. Fracture fragments were fixed with reconstruction plates and cortical screws along the posterior column, and supplemental screws stabilized the anterior column (Fig. 3).

Figure 3: Anteroposterior radiograph of the pelvis following open reduction and internal fixation of the acetabular fracture, demonstrating anatomically restored acetabular alignment with stable reconstruction plates and screws along the involved column, and a concentrically reduced hip joint.

Intraoperative fluoroscopy and post-operative radiographs confirmed anatomic reduction and restoration of the weight-bearing dome. Toe-touch weight-bearing was allowed for 8 weeks, followed by progressive loading to full weight-bearing by 12 weeks based on clinical and radiographic evidence of union.

Clinical course after fixation

Radiographs at 3 months demonstrated consolidation across the fracture lines with stable hardware. At 6 months, the patient walked without aids, reported minimal pain, and had near-normal hip range of motion; the Harris hip score (HHS) measured 87. At 15 months, he reported gradually increasing groin pain, stiffness, and difficulty with prolonged standing and walking. Examination revealed painful limitation of flexion beyond 60°, reduced abduction and internal rotation, and an antalgic gait. Radiographs at 18 months showed femoral-head collapse, subchondral sclerosis, joint-space narrowing, superior migration of the femoral head, and resorption of the superolateral acetabular rim, consistent with Ficat-Arlet stage IV AVN (Fig. 4). Several acetabular screws showed periscrew lucency, indicating loosening. Non-operative measures, including activity modification, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and physiotherapy, failed to relieve symptoms. Conversion THR was, therefore, planned.

Figure 4: Anteroposterior radiograph of the pelvis demonstrating Ficat-Arlet stage IV avascular necrosis of the femoral head, with collapse, joint space narrowing, and superior migration.

Treatment

Pre-operative workup included inflammatory markers, hip aspiration, and cultures, which excluded infection. CT was reviewed to assess hardware position, acetabular bone stock, and defect morphology. Implant selection included a porous metal multi-hole acetabular cup, highly cross-linked polyethylene liner, uncemented tapered femoral stem, and a 36 mm femoral head.

Conversion THR was performed under combined spinal-epidural anesthesia through the previous Kocher-Langenbeck incision (Fig. 5). Dense scar tissue required meticulous dissection to identify anatomical planes. The sciatic nerve was encased in fibrous tissue posterior to the short external rotators and was carefully exposed and mobilized throughout its course to prevent traction or thermal injury.

Figure 5: Anteroposterior radiograph of the pelvis following total hip arthroplasty, demonstrating a well-positioned uncemented acetabular cup secured with multiple screws and a stable femoral stem, with restoration of hip center, leg length, and overall joint alignment.

The external rotators and posterior capsule were released, providing circumferential acetabular exposure. Hardware that would interfere with reaming or cup placement was removed; deeply seated screws that did not obstruct the planned component position were left in place to preserve bone.

The femoral head was dislocated and removed and showed extensive collapse and degenerative changes. It was prepared as morselized autograft for acetabular defect reconstruction. Fibrous tissue and residual cartilage were debrided from the acetabular fossa. Sequential reaming from 44 mm to 56 mm created a hemispherical cavity with bleeding cancellous bone. Posterosuperior cavitary defects were filled with compacted morselized femoral-head autograft to reconstitute the rim and support the cup. A 58 mm uncemented porous metal acetabular shell was impacted in approximately 40–45° of abduction and 15–20° of anteversion. Multiple 6.5 mm cancellous screws were placed into the posterior column, gluteal pillar, ischium, and anterior column to enhance initial stability. A highly cross-linked polyethylene liner was locked into the shell. The femoral canal was prepared with broaches to accept an uncemented tapered titanium stem (size 4) achieving axial and rotational stability. A 36 mm cobalt-chromium head with +4 mm offset was mounted on the stem to restore leg length and offset. Trial reduction confirmed stable range of motion without impingement. The definitive head was implanted, and the hip was reduced. Posterior capsule and external rotators were repaired anatomically to improve stability, and the wound was closed over a drain.

Outcome and follow-up

The patient received thromboprophylaxis with low-molecular-weight heparin and early physiotherapy. Partial weight-bearing with a walker started on post-operative day 1, with progression to full weight-bearing as tolerated over 3 weeks. No dislocation, wound complication, or early infection occurred [1,2,3,4]. Radiographs at 6 weeks showed a well-positioned cup and stem with intimate contact between the cup and host bone and maintained graft position. At 3 months, the patient reported pain-free walking with a near-normal gait, and hip range of motion was 0–100° flexion, 0–40° abduction, and 0–20° internal rotation. At 6 months, he walked independently without support and performed activities of daily living without limitation; HHS measured 80. At 1-year follow-up, the patient remained pain-free with independent ambulation. Radiographs displayed stable implant position, evidence of osseointegration of the femoral stem, and incorporation of acetabular autograft. HHS was 76, reflecting sustained good function.

This case highlights the risk of late AVN and post-traumatic arthritis in young patients after acetabular fracture fixation and demonstrates that conversion THR, although demanding, provides reliable symptom relief and function when executed with defined principles [1,2,3,4,5]. Both-column patterns with posterior wall involvement carry high risk for vascular compromise and cartilage damage. Even with anatomic reduction and stable fixation, the femoral head may lose its blood supply at the time of injury, leading to collapse within 2 years. The present case reflects this pattern, with excellent early outcome followed by rapid deterioration at 18 months. Conversion THR after acetabular fixation presents several technical challenges: Distorted bone morphology, presence of hardware, acetabular rim loss, and dense scar tissue around the sciatic nerve and posterior structures [3,4,5,7]. The strategy in this case integrated selective hardware removal, use of a porous multi-hole cup with screw fixation, autograft reconstruction of contained defects, and meticulous nerve protection. Porous metal cups with multiple screw options improve fixation and survival in acetabular reconstructions after fractures compared with older cemented designs. Autogenous femoral-head graft effectively manages contained acetabular defects, permits biological incorporation, and reduces the need for bulk allograft or cages. Larger femoral heads and careful soft-tissue repair reduce instability, which remains more common in conversion THR than primary THR. Reported series describe HHS in the 70–80 range and complication rates of 10–20% in similar conversions. The present patient’s HHS of 76 at 1 year and absence of early major complications fall within this expected range. Existing literature predominantly focuses on elderly patients with degenerative disease; long-term durability of conversion THR in young, active post-traumatic patients remains less clearly defined [3,4,5,7,10]. Larger studies with extended follow-up will clarify survivorship and identify optimal bearing surfaces and implant design [3,8,9,10].

Conversion THR after acetabular fracture fixation in young adults represents a technically demanding procedure but yields reliable pain relief and functional improvement when performed with thorough pre-operative planning, selective hardware removal, reconstruction of contained acetabular defects with autograft, modern porous metal cups with multiple screws, and meticulous sciatic nerve protection and posterior soft-tissue repair. Young patients with complex acetabular fractures require clear counseling regarding the risk of late AVN and post-traumatic degeneration and systematic follow-up to detect deterioration early and offer timely salvage THR.

Young adults with anatomically fixed acetabular fractures frequently develop femoral-head avascular necrosis and progressive hip dysfunction; conversion total hip replacement using selective hardware removal, autograft reconstruction, porous acetabular components, and careful sciatic-nerve protection reliably restores a stable, pain-free hip.

References

- 1. Cimerman M, Kristan A, Jug M, Tomaževič M. Fractures of the acetabulum: From yesterday to tomorrow. Int Orthop 2021;45:1057-64. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 2. Li J, Jin L, Chen C, Zhai J, Li L, Hou Z. Predictors for post-traumatic hip osteoarthritis in patients with transverse acetabular fractures following open reduction internal fixation: A minimum of 2 years’ follow-up multicenter study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2023;24:811. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 3. Shaker F, Esmaeili S, Nakhjiri MT, Azarboo A, Shafiei SH. The outcome of conversion total hip arthroplasty following acetabular fractures: A systematic review and meta-analysis of comparative studies. J Orthop Surg Res 2024;19:83. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 4. Gautam D, Gupta S, Malhotra R. Total hip arthroplasty in acetabular fractures. J Clin Orthop Trauma 2020;11:1090-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 5. Nicol GM, Sanders EB, Kim PR, Beaulé PE, Gofton WT, Grammatopoulos G. Outcomes of total hip arthroplasty after acetabular open reduction and internal fixation in the elderly-acute vs delayed Total Hip Arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 2021;36:605-11. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 6. Solano A, Serra M, Mereddy P, Godinho M, Le Baron M, Mauffrey C. Acetabular reconstruction: From fracture pattern to fixation – part 1. Injury 2025;56:112578. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 7. Tannast M, Najibi S, Matta JM. Two to twenty-year survivorship of the hip in 810 patients with operatively treated acetabular fractures. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2012;94:1559-67. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 8. Matta JM. Fractures of the acetabulum: Accuracy of reduction and clinical results in patients managed operatively. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1996;329:141-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 9. Harris WH. Traumatic arthritis of the hip after dislocation and acetabular fractures: Treatment by mold arthroplasty. An end-result study using a new method of result evaluation. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1969;51:737-55. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 10. Bombaci H, Deniz G, Tekin M. Outcomes of delayed conversion total hip arthroplasty following operatively treated acetabular fractures. J Orthop Traumatol 2022;23:12. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]