Ulnar shortening osteotomy with temporary DRUJ fixation is an effective option for late-presenting distal radius physeal injuries, even in adolescents requiring >15 mm shortening, with excellent satisfactory functional outcomes.

Dr. Faisal Fahad Almalilk, Department of Pediatric Orthopedic, Orthopedic and Spinal Surgery Center, King Saud Medical City, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. E-mail: faisal.almalikk@gmail.com

Introduction: Pediatric forearm fractures are very common. The distal radius growth physis contributes the majority of the radial length and nearly half of the entire upper extremity. Although growth arrest associated with physeal fractures is rare but the sequelae can be very detrimental and challenging. Partial or complete distal radius physis arrest can lead to radial shortening, alteration of radial tilt or inclination, distal radioulnar joint (DRUJ) incongruity, ulnocarpal abutment syndrome, and injury to the triangular fibrocartilage complex. Post-traumatic distal radius physis arrest is a serious complication that can lead to several disabilities. These disabilities could be devastating as it is related to the functional status of the wrist. In the literature, there are few studies reported post-traumatic distal radius growth arrest. Our case is bilateral post-traumatic distal radius growth arrest with positive ulnar variance that is limiting the patient’s wrist function.

Case Report: A 13-year-old boy presented to the outpatient department with bilateral wrists pain and deformities, 6 years after sustaining bilateral distal radius fractures, which was managed conservatively at that time. On examination, the patient had obvious bilateral wrists deformities and limitation of range of motion (ROM). Radiographic investigations showed: Bilateral central distal radius physeal osseous bar in the background of positive ulnar variance and dorsal subluxation of the DRUJ. After discussing treatment options with his parents, the patient was treated surgically, starting with the left side by ulnar shortening osteotomy and temporary DRUJ fixation. After 8 weeks from the surgical operation, the patient was referred for physiotherapy for gradual supervised sessions to regain full ROM and strength. One year follow-up, the patient showed near normal wrists activity with satisfactory outcome for him and his family, so the same surgical operation was done to the right side.

Conclusion: The treatment of these types of injuries is highly controversial. Options could vary from case to case. We do believe that ulnar shortening osteotomy with temporary DRUJ fixation should be considered in treating late presenting distal radius physeal injury in adolescent patients, aiming for an absolute great outcome.

Keywords: Wrist fractures, physeal injury, ulnar variance, distal radius growth arrest.

Pediatric forearm fractures are a common injury that accounts for 40% of all pediatric long bone fractures [1,2]. The distal radius growth physis contributes around 75% of the radial length, and 40% of the entire upper extremity [3,4]. Although growth arrest associated with physeal fractures is a rare result that accounts for about 1% to 7% of the cases [5,6]. The sequleae can be very detrimental and challenging to address clinically and radiologically. Partial or complete distal radius physis arrest can lead to radial shortening, alteration of radial tilt or inclination, distal radioulnar joint (DRUJ) incongruity, ulnocarpal abutment syndrome, and injury to the triangular fibrocartilage complex (TFCC) [7,8]. These consequences may manifest in gross deformity includes chronic wrist pain, limitation of wrist range of motion (ROM), and decreased grip strength [9]. We present a delayed case with bilateral distal radius growth arrest, positive ulnar variance with gradual wrists deformity and pain managed by staged bilateral acute ulnar shortening osteotomy, ulnar permanent epiphysiodesis, and DRUJ stabilization. The patient had an old medical history with distal radius Salter-Harris type II fractures, which was managed conservatively with close reduction and casting at the age of 7.

A 13-year-old male right-hand-dominant suffered bilateral distal radius fractures (Salter-Harris II) from being involved in a road traffic accident as a passenger at the age of 7-years-old. He was managed conservatively with closed reduction and casting in another institution. He continued to follow-up for a duration of 6 weeks until signs of radiological healing were achieved and then he was discharged. At the age of 13, the patient presented to our clinic, which is 6 years after his initial injury, with complaints of long-standing bilateral wrist pain and gross gradual wrist deformities, which was observed by parents and affected his daily activities. Thorough physical examination of bilateral wrists showed prominent bilateral ulnar styloids, significant limitation of ROM and supination arc (Table 1), as well as hyper-laxity of the DRUJ.

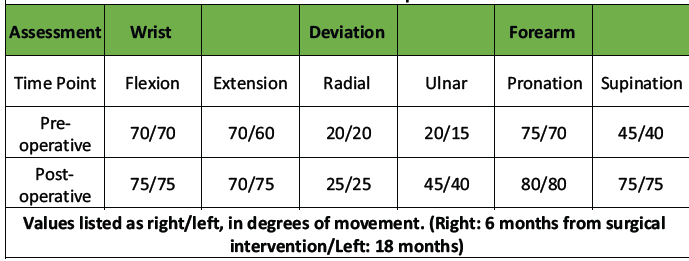

Table 1: Bilateral wrist range of motion pre -operatively and at the time of the most recent follow -up

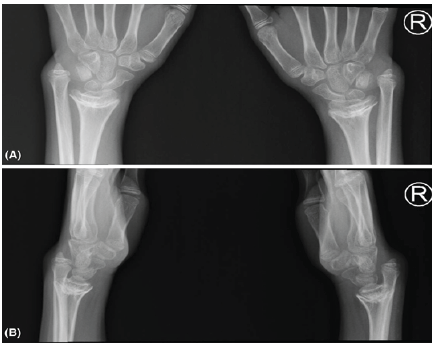

No point tenderness at the level of the elbow or shoulders. His distal neurovascular status intact. Furthermore, there was a positive ulnar ballottement test and a positive ulnar impaction test as well. Comprehensive radiological investigations, including X-Rays (Fig. 1), and magnetic resonance images revealed multiple abnormalities.

Figure 1: (a) Pre-operative of bilateral wrist X-ray anteroposterior view. (b) Pre-operative of bilateral wrist X-ray lateral view.

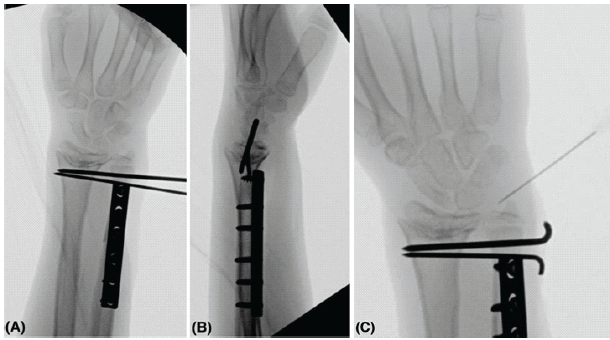

The radiographs showed bilateral symmetrical central distal radius physeal osseous bar in the background of positive ulnar variance and dorsal subluxation of the DRUJ. MRI showed evidence of stretching of the dorsal and volar radioulnar ligaments but no evidence of tears on the distal radioulnar ligament or TFCC, and a congruent distal radius joint line without arthritic changes. Due to the patient’s symptoms and deformity, the boy and parents were informed about his condition and the possible management plan for the complicated wrist joint, and they agreed to proceed with operative treatment, starting with the left wrist, which was the non-dominant but the more painful wrist joint. At 6-years and 6-months post-injury, the patient was prepared electively and underwent left side ulnar shortening osteotomy with 3.5 mm 6-holes locking compression plate fixation through direct ulnar approach, with a shortening of 1.7 cm was made as planned pre-operatively, followed by permanent distal ulnar physeal epiphyseodesis with 4.5 mm cannulated drill bit under guidance of image intensifier. The ulnar osteotomy was performed with an oscillating saw 5cm proximal to the joint line. Furthermore, intraoperatively, the patient underwent distal radioulnar joint (DRUJ) temporary fixation with two Kirschner-wires, size 2.5 mm in full supination and ulnar-to-radial fashion parallel to the joint line, followed by steroid injection of TFCC to relieve the pain (Fig. 2).

Figure 2: (a) Final intra-op left wrist anteroposterior X-ray. (b) Final intra-op left wrist lateral X-ray. (c) Intra op left wrist X-ray while doing a steroid injection of the triangular fibrocartilage complex to relieve the pain.

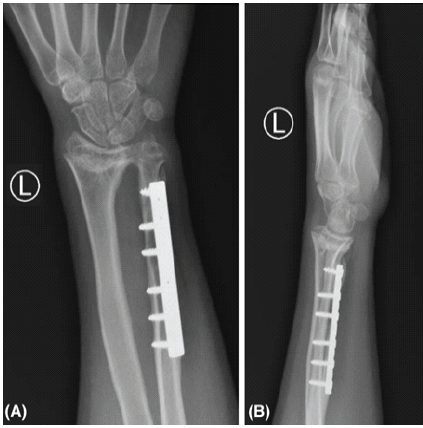

The k-wires were bent and cut before closure of the wound, which was done subcuticularly. The closure was done with vicryl 2–0 for the subcutaneous tissue and monocryle 3–0 subcuticular for the skin. The patient was positioned on a backslab with near full forearm supination position post-correction. The boy had an uneventful post-operative course, and he was evaluated 2 weeks post-operative, which showed a well-healed surgical wound, then 8 weeks post-operativelyK-wires and backslab were removed. After removal of K-wires and backslab, the patient was referred to physiotherapy early on treatment with gradual supervised sessions from regaining range of motion to full-weight-bearing instruction and increasing the hand/wrist power and strength. He continued follow-ups in our pediatric orthopedic clinic after 2, 4, and 8 months consecutively after removal of the slab. Clinically, the patient was off-pain and had increased ROM of the wrist with almost full forearm supination, full forearm pronation, full wrist radial and ulnar deviation, and near full wrist flexion and extension in the final follow-up at 1 year post-surgical intervention (Table 1). Radiologically, the ulnar bone was fully healed and well-aligned radioulnar and wrist joint, and carpal bones (Fig. 3).

Figure 3: (a) Final postoperative left wrist anteroposterior X-ray. (b) Final post-operative left wrist lateral X-ray.

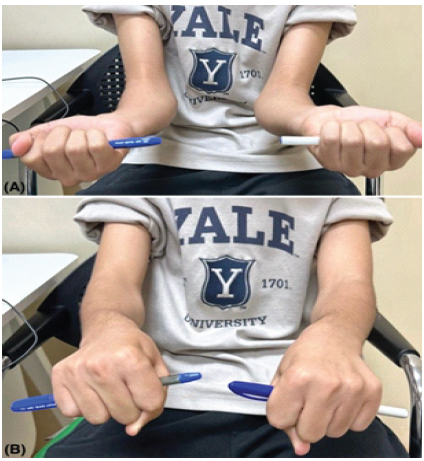

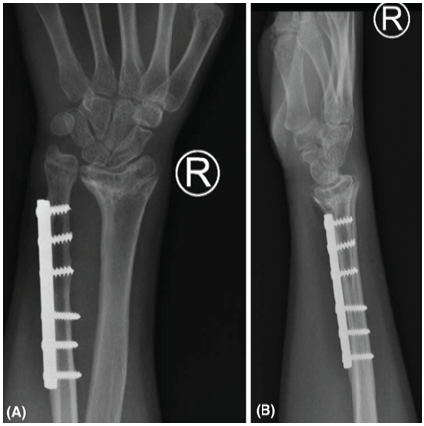

In-terms of patient-related outcome, the patient and his parents were extremely satisfied with the surgical outcome in terms of increased functional ROM and cosmetic appearance of the hand and wrist. After these satisfactory results and outcomes, the patient and his parents were asked to proceed with operative treatment for the right wrist. At 7 years and 6 months post-injury, he underwent the exact same surgical intervention for the right side under general anesthesia. The ulnar shortening was almost 1.9 cm to aligned distal radioulnar joint. The boy had an uneventful post-operative course, and he was evaluated at 2 and 8 weeks post-surgical intervention, as same as previous post-operative course then to be followed by 2, 4, and 8 months consecutively. At 4 months post-operative, clinical evaluation demonstrated improved ROM, including supination/pronation, with pain-free wrist (Fig. 4 and Table 1). The radiographs showed adequate union of the osteotomy site with an ulnar neutral wrist in aligned position (Fig. 5). In-terms of patient-related outcome, the patient and his family were satisfied with the results. At the time of reporting the case, the patient is 6 months post-surgical intervention for the right side with an improving range of motion, and he is currently following with physiotherapy along with our pediatric orthopedic clinic.

Figure 4: (a) Bilateral wrist clinical photo in almost near full supination. (b) Bilateral wrist clinical photo in almost near full pronation.

Figure 5: (a): Final right wrist anteroposterior X-ray. (b) Final right wrist lateral X-ray.

The forearm fractures in the pediatric population are a common injury [1,2]. Salter-Harries classification is used to classify the fractures related to physeal injuries. Salter-Harries fracture type II is the most common fracture account for approximately 75%, while SH type V is the least common, with <1% prevalence [4,10]. Salter Harries type V fracture is a very tricky type of physeal injury and well known to be diagnosed retrospectively with later presentation of clinical or radiological evidence of deformity, as initial images mostly do not show a clear injury, as our presenting case. This type is considered the least favorable prognosis type with growth arrest, in which the mechanism is a compression injury transmitted through the physis and causes a permanent damage to the physis [10]. There are multiple surgical techniques used to manage of complete physeal injury of the distal radius include gradual distraction osteogenesis lengthening of the radius, acute radial correction-lengthening osteotomy, and acute ulnar shortening osteotomy with either internal or external fixation devices. The use of these techniques depends on the patient’s age, time of injury, and how much growth potential remaining in the patient’s physis. As our patient has a good body built with near skeletal maturity bone age, the patient elected for ulnar shortening osteotomy with DRUJ fixation. In our opinion, the use of shortening osteotomy in the upper extremity is a more tolerable option functionally and cosmetically in compare to the lower limb with more quicker healing time and early physiotherapy. The injury has been occurred, and our concerns were to regain upper limb ROM specially supination and ulnar deviation, and to decrease the patient’s reported pain. In addition, the use of this technique decreases the reported complication of other option, such as pin site infection due to external fixator or risk of delayed union due to grafting in the lengthening option. Hove and Engesater reported as series of 6 patients, with 3 patients underwent ulnar shortening and 3 radial lengthening [9]. The shortening group due to moderate malalignment, with 1 patient underwent 4 mm shortening with distal ulna epiphysiodesis, and 2 patients underwent 8 mm shortening with TFCC repair without reported complications. Waters et al have done a series of 30 cases with 18 patients underwent ulnar shortening osteotomy with an average 4.5 mm shortening from positive variance to neutral variance without reported complications [11]. In the same series, the highest shortening was 12.5 mm of the ulnar shortening group. These results supporting ulnar shortening osteotomy as a valid option with good results post-operatively and without reported complications. The reported shortening levels in both studies were 8 mm and 12.5 mm, respectively, while in our study, we shorten up to 17 mm and 19 mm as time passed between both procedures. There is no clear-cut number of shortening in literature, which ulnar shortening osteotomy will be used as an option in compare to other techniques. We believe the ulnar shortening is a good option in case of a near skeletal maturity patient, without severe radial angular deformity, and without big radial-ulnar length variance (>20 mm). Other options with distal radius physeal injury include radius corrective osteotomy and distraction osteogenesis. De Oliveira et al., reported two cases with severe angular deformity and shortening who underwent acute open wedge osteotomy of the radius with iliac crest autograft [12]. The reported outcomes were satisfying with promising technique, especially for severe angular deformities. Page and Szabo reported four cases who underwent distraction osteogenesis with good outcomes post-operatively, but the patients experienced a long journey of management, with 2 patients having pin site infection, and 1 patient had elbow stiffness, and 2 patients required unplanned return to operation theatre [13]. They summarize their experience with the need of committed patient and surgeon to treat the complication of distal radius physeal injury with distraction osteogenesis. We believe all techniques are valid options with each have its own advantages and disadvantages based on patient type.

Ulnar shortening osteotomy with temporary DRUJ fixation is a good option to treat late presenting distal radius physeal injury (SH V) in adolescent patient even if there is 15–20 mm variance with easy reduction intraoperatively, an uneventful post-operative course, quick healing process radiologically, non-painful physiotherapy, and near full ROM after 2-years of follow-up.

Ulnar shortening osteotomy with temporary DRUJ fixation showed satisfactory, excellent results in the treatment of late presenting distal radius physeal injury with limited wrist functional status.

References

- 1. Chung KC, Spilson SV. The frequency and epidemiology of hand and forearm fractures in the United States. J Hand Surg Am 2001;26:908-15. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 2. Cheng JC, Shen WY. Limb fracture pattern in different pediatric age groups: A study of 3,350 children. J Orthop Trauma 1993;7:15-22. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 3. Ottomeyer C, Iobst CA. Physeal fracture of the distal radius. In: Pediatric Orthopedic Trauma Case Atlas. Germany: Springer; 2020. p. 289-94. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 4. Noonan KJ, Price CT. Forearm and distal radius fractures in children. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 1998;6:146-56. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 5. Lee BS, Esterhai JL Jr., Das M. Fracture of the distal radial epiphysis. Characteristics and surgical treatment of premature, post-traumatic epiphyseal closure. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1984;185:90-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 6. Buterbaugh GA, Palmer AK. Fractures and dislocations of the distal radioulnar joint. Hand Clin 1988;4:361-75. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 7. Kallini JR, Fu EC, Shah AS, Waters PM, Bae DS. Growth disturbance following intra-articular distal radius fractures in the skeletally immature patient. J Pediatr Orthop 2020;40:e910-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 8. Khan H, Green G, Arnander M, Umarji S, Gelfer Y. What are the risk factors and presenting features of premature physeal arrest of the distal radius? A systematic review. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol 2021;31:893-900. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 9. Hove LM, Engesæter LB. Corrective osteotomies after injuries of the distal radial physis in children. J Hand Surg (Eur Vol) 1997;22:699-704. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 10. Levine RH, Thomas A, Nezwek TA, Waseem M. Salter-Harris fracture. In: StatPearls. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing; 2023. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 11. Waters PM, Bae DS, Montgomery KD. Surgical management of posttraumatic distal radial growth arrest in adolescents. J Pediatr Orthop 2002;22:717-24. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 12. De Oliveira RK, Serrano PJ, Badia A, Ferreira MT. Corrective osteotomy after damage of the distal radial physis in children: Surgical technique and results. Tech Hand Up Extrem Surg 2011;15:236-42. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 13. Page WT, Szabo RM. Distraction osteogenesis for correction of distal radius deformity after physeal arrest. J Hand Surg Am 2009;34:617-26. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]