Persistent or atypical pubic or suprapubic pain unresponsive to standard therapy should prompt evaluation for underlying tuberculous osteomyelitis, as dual infection with MRSA, though rare, can occur and requires tissue diagnosis for confirmation.

Dr. Vinod Xavier, Department of Internal Medicine, Aster Medcity, Kuttisahib Road Cheranelloor, South Chittoor, Kochi - 682027, Kerala, India. E-mail: winuku@gmail.com

Introduction: Osteomyelitis of the pubic symphysis is rare, representing less than one percent of all osteomyelitis cases, and is frequently misdiagnosed as genitourinary pathology owing to overlapping symptoms and anatomical proximity. Tuberculous involvement at this site is exceptional, and concurrent infection with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) remains infrequently documented. This case contributes to orthopedic literature by demonstrating how reliance on blood and pus cultures alone can delay recognition of occult mycobacterial disease in culture-discordant pelvic osteomyelitis, reinforcing the indispensable role of surgical biopsy and histopathology in guiding combined antimycobacterial and antistaphylococcal therapy.

Case Report: A 40-year-old South-Asian woman with hypothyroidism and recurrent urinary tract infections presented with 2 weeks of progressive suprapubic pain radiating to both lower limbs and high-grade fever. Examination revealed fever, suprapubic tenderness, and restricted bilateral hip movements. Laboratories showed neutrophilic leukocytosis and elevated C-reactive protein. Blood culture grew MRSA; urine and ultrasound-guided prepubic pus cultures were sterile. Magnetic resonance imaging confirmed bilateral pubic bone osteomyelitis, superior rami involvement, abscesses, and myositis. Symptoms persisted despite intravenous teicoplanin, prompting surgical debridement. Curetted bone histopathology demonstrated necrotizing granulomatous inflammation with acid-fast bacilli, establishing tuberculous osteomyelitis complicated by secondary MRSA bacteremia.

Conclusion: Clinicians managing non-resolving pubic osteomyelitis must pursue tissue diagnosis for mycobacterial infection, even when pyogenic pathogens are isolated, and pus is culture-negative. Prompt initiation of anti-tubercular therapy alongside targeted antibiotics yields rapid recovery. This report advances orthopedic infectious disease practice by providing a reproducible diagnostic algorithm for polymicrobial drug-resistant pelvic sepsis, with immediate relevance to orthopedics, infectious diseases, urology, and gynecology in tuberculosis-endemic regions.

Keywords: Tuberculous osteomyelitis, pubic symphysis, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, co-infection, extrapulmonary tuberculosis

Osteomyelitis of the pubic symphysis and bones is an uncommon clinical entity, accounting for <1% of all osteomyelitis cases [1]. Its insidious onset, non-specific symptoms, and anatomical proximity to genitourinary structures often lead to diagnostic delays, with initial misattribution to more common conditions such as urinary tract infections (UTIs), pelvic inflammatory disease, or musculoskeletal strain [2]. While bacterial pathogens, particularly Staphylococcus aureus, are the most frequent etiological agents in acute pubic osteomyelitis [3], tuberculous involvement of the pubic skeleton is exceedingly rare and sparsely documented in the literature [4,5]. Tuberculous osteomyelitis itself constitutes approximately 1–3% of extrapulmonary tuberculosis cases [6,7]. It typically presents with chronic localized pain, low-grade fever, and constitutional symptoms, but can remain clinically silent for prolonged periods. Diagnosis is often complicated by overlapping features with pyogenic infections, and definitive diagnosis requires histopathological or microbiological confirmation [6,8]. Co-infection with methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) is rare and poses additional therapeutic challenges [9]. We present a diagnostically challenging case of tuberculous osteomyelitis of the pubic bones in a middle-aged South Asian woman with a history of recurrent UTIs, complicated by secondary MRSA infection. This case highlights the importance of maintaining a high index of suspicion for skeletal tuberculosis in patients with atypical pelvic pain and non-resolving presumed genitourinary infections, especially in endemic settings.

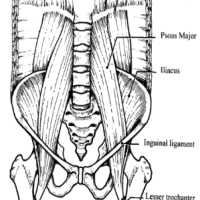

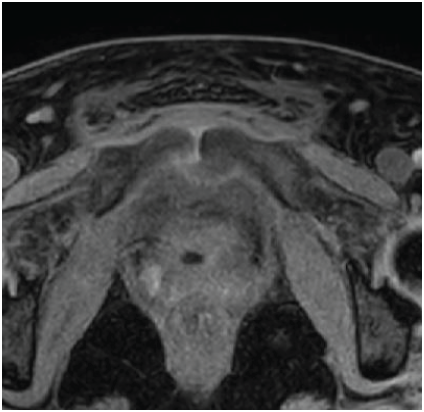

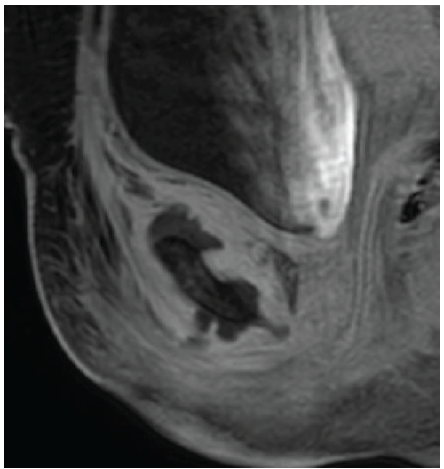

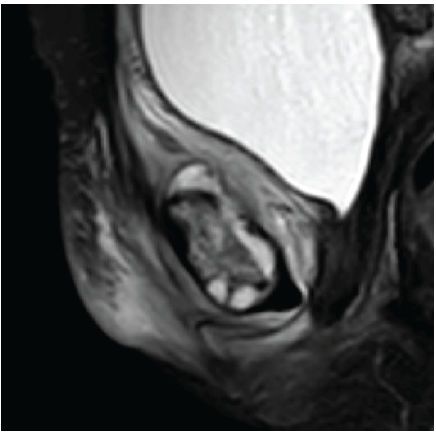

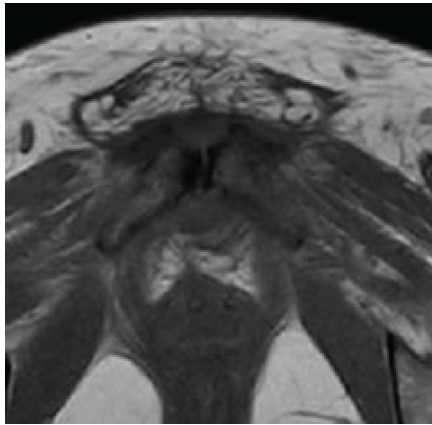

A 42-year-old South Asian woman with a history of hypothyroidism and recurrent UTIs presented with a 2-week history of lower abdominal pain radiating to both lower limbs, associated with high-grade intermittent fever. The pain was spontaneous in onset, progressive, and unrelated to trauma. She had previously received multiple short courses of antibiotics for recurrent UTIs. She presented to our center 10 days after the onset of symptoms. On evaluation, she was febrile (temperature 102°F), with suprapubic tenderness and restriction of active and passive hip movements bilaterally. Initial laboratory investigations revealed neutrophilic leukocytosis (total leukocyte count: 15,000/µL; neutrophils: 13,600/µL) and elevated C-reactive protein (195 mg/L). Urine routine examination demonstrated numerous red blood cells but no pyuria. A contrast-enhanced computed tomography renal stone survey showed perinephric stranding in the retropubic space suggestive of cystitis, with no evidence of collections, hematoma, or pelvic bone fractures. She was empirically started on intravenous piperacillin-tazobactam for presumed acute cystitis, given her history of recurrent UTIs. However, urine culture showed no growth after 48 h, while blood cultures grew MRSA. Antibiotics were escalated to intravenous teicoplanin (400 mg twice daily). Despite 48 h of appropriate therapy, she continued to have high-grade fever and worsening excruciating suprapubic pain radiating to the groin and medial thighs, severely limiting her mobility. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the pelvis with contrast revealed osteomyelitis of the bilateral pubic bones and superior pubic rami, with abscesses (10 mL and 1.5 mL) around the pubic symphysis, fluid collections in the right adductor and obturator externus muscles, and edema of the obturator internus, externus, and pectineus muscles (Figs. 1, 2, 3, 4).

Figure 1: Axial T2-weighted magnetic resonance imaging of the pelvis showing marrow edema and signal alteration involving the bilateral pubic bones and superior pubic rami, consistent with osteomyelitis.

Figure 2: Sagittal magnetic resonance imaging image demonstrating a well-defined collection in the superior aspect of the pubic symphysis (approximately 10 cc), suggestive of an abscess. The collection shows peripheral enhancement without extension into the abdominal cavity.

Figure 3: Sagittal magnetic resonance imaging showing a smaller abscess (~1.5 cc) in the inferior aspect of the pubic symphysis. Associated edematous changes are noted in the adductor muscle compartment, obturator externus, and pectineus muscles.

Figure 4: Axial T1-weighted magnetic resonance image of the pelvis showing altered marrow signal intensity involving the bilateral pubic bones and superior pubic rami, consistent with osteomyelitis. The pubic symphysis appears widened with adjacent soft-tissue edema and early abscess formation. Surrounding muscular edema is noted in the adductor and obturator groups.

Ultrasound-guided aspiration of a prepubic abscess yielded 2 mL of pus, which on culture grew MRSA. Tuberculosis diagnostic panel was negative at this stage. Given ongoing pain and abscess formation, she underwent orthopedic surgical exploration with soft tissue dissection, aspiration of abscess, and curettage of underlying bone under spinal anesthesia. The curetted bone specimen was sent for histopathological examination and microbiological culture.

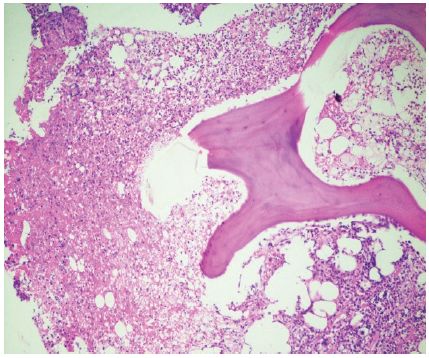

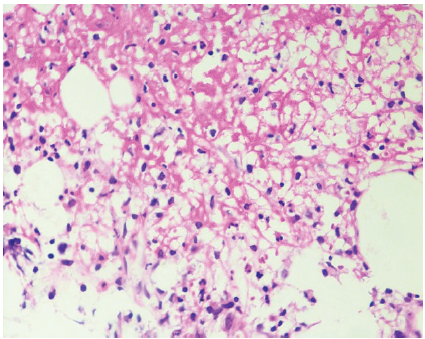

Histopathology revealed necrotizing granulomatous osteomyelitis consistent with a mycobacterial etiology, and Ziehl–Neelsen staining demonstrated occasional acid-fast bacilli (Figs. 5 and 6). Based on these findings, a diagnosis of tubercular osteomyelitis of the pubic symphysis with secondary MRSA infection was established.

Figure 5: Photomicrograph showing bony trabeculae on the right and necrotic material with inflammatory infiltrate on the left side (Hematoxylin and Eosin, ×100).

Figure 6: Photomicrograph showing necrotic material with epithelioid histiocytes, neutrophils, and plasma cells, consistent with necrotizing granulomatous inflammation (Hematoxylin and Eosin, ×400).

The patient was initiated on standard first-line anti-tubercular therapy consisting of rifampicin 600 mg/day, isoniazid 300 mg/day, pyrazinamide 1,500 mg/day, and ethambutol 1,000 mg/day. Anti-tubercular therapy was continued for a total duration of 12 months. For the concurrent MRSA infection, she was initially treated with intravenous daptomycin, which was later transitioned to oral levofloxacin 750 mg once daily based on clinical response and culture clearance. Anti-staphylococcal therapy was administered for a total duration of 3 months. During the course of follow-up, the patient developed a surgical site infection in the suprapubic region, which was managed with wound debridement and application of vacuum-assisted closure therapy, following which the wound healed satisfactorily.

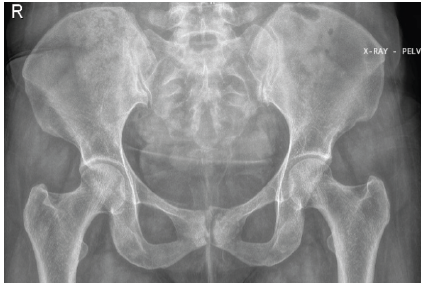

At follow-up, the patient demonstrated sustained clinical improvement with complete resolution of fever and significant recovery of mobility. At the last follow-up visit (3 months), plain radiographs of the pelvis showed no progression of bony destruction and features consistent with healing osteomyelitis (Fig. 7).

Figure 7: Anteroposterior radiograph of the pelvis at follow-up showing preserved pelvic alignment with no evidence of progressive bony destruction of the pubic symphysis or adjacent pubic rami. Findings are consistent with radiological stability/healing following combined anti-tubercular and anti-staphylococcal therapy.

Pubic symphysis osteomyelitis is an uncommon condition and is frequently misdiagnosed because of its insidious onset, non-specific symptoms, and close anatomical proximity to the genitourinary and pelvic organs [1,2]. Patients often present with suprapubic or groin pain and fever, leading to initial attribution to UTI or musculoskeletal pathology. S. aureus, including MRSA, is the most commonly implicated pathogen in acute pubic osteomyelitis and pelvic sepsis [3,9]. However, persistence of symptoms despite appropriate culture-directed anti-staphylococcal therapy should prompt reconsideration of the diagnosis and evaluation for atypical organisms. Tuberculous osteomyelitis accounts for a small proportion of extrapulmonary tuberculosis and rarely involves the pubic bones, making diagnosis particularly challenging [4,5,6,7,8,10]. Radiological findings may overlap with pyogenic infection, and microbiological confirmation is often limited by the paucibacillary nature of skeletal tuberculosis. Recent reports describe pubic symphysis tuberculosis as a rare presentation that often mimics other pelvic disorders and requires MRI and tissue biopsy for definitive diagnosis [11]. Contemporary case series have also broadened understanding of pubic bone osteomyelitis by documenting varied presentations and outcomes beyond classic pyogenic causes [12]. The principal strength of this case lies in demonstrating a rare coexistence of tuberculous osteomyelitis with secondary MRSA infection and highlighting the risk of diagnostic anchoring when a pyogenic pathogen is isolated. Surgical biopsy with histopathological examination proved decisive in establishing the diagnosis and guiding appropriate combined therapy. The limitations of this report include its single-case design and limited microbiological confirmation of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Nevertheless, this case underscores the importance of tissue diagnosis in non-resolving pubic osteomyelitis, particularly in tuberculosis-endemic regions, to ensure timely and targeted treatment.

Persistent symptoms in pubic symphysis osteomyelitis, despite appropriate antibiotic therapy, warrant biopsy to evaluate for tuberculosis, even when pyogenic organisms are present. Combined antimicrobial therapy yields favorable outcomes when diagnosis is timely.

Osteomyelitis of the pubic symphysis, though rare, should be considered in patients with persistent suprapubic or groin pain unresponsive to conventional therapy for presumed urinary or gynecologic infections. Even when a pyogenic pathogen such as MRSA is identified, failure to improve should prompt evaluation for underlying tuberculosis, particularly in endemic areas. Tissue diagnosis through biopsy or curettage remains essential for detecting atypical or dual infections and ensuring appropriate, targeted therapy.

References

- 1. Kato H, Takeda T, Yamaguchi T. Osteomyelitis of the pubic symphysis: A rare condition mimicking urinary tract infection. Case Rep Infect Dis 2017;2017:2792635. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 2. Lew DP, Waldvogel FA. Osteomyelitis. Lancet 2004;364:369-79. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 3. Ross JJ, Hu LT. Septic arthritis of the pubic symphysis: Review of 100 cases. Medicine (Baltimore) 2003;82:340-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 4. Raoult D. Necrotizing granulomatous osteomyelitis due to Mycobacterium tuberculosis: A report of four cases. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 1999;18:333-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 5. Tuli SM. Tuberculosis of the Skeletal System (Bones, Joints, Spine and Bursal Sheaths). 4th ed. New Delhi: Jaypee Brothers Medical Publishers; 2010. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 6. Agarwal R, Gupta R. Tuberculous osteomyelitis: A diagnostic dilemma. Indian J Tuberc 2013;60:197-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 7. David MZ, Daum RS. Community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: Epidemiology and clinical consequences of an emerging epidemic. Clin Microbiol Rev 2010;23:616-87. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 8. Zhang Y. Tuberculous osteomyelitis: Diagnosis and treatment. J Clin Orthop Trauma 2016;7:285-91. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 9. David MZ, Daum RS. Community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: Epidemiology and clinical consequences of an emerging epidemic. Clin Microbiol Rev 2010;23:616-87. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 10. Abdelwahab IF, Bianchi S, Martinoli C, Klein M. Tuberculous osteomyelitis: A review with illustrative cases. Eur Radiol 2016;26:1311-21. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 11. Oliveira Pinheiro F, Madureira P, Seabra Rato M, Costa L. Tuberculous osteomyelitis of the pubic symphysis – a case report of a rare entity mimicking spondyloarthritis. ARP Rheumatol 2023;2:74-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 12. Lewis AM, Vaynrub M, Mead PA, Betchen M, Kamboj M, Kaltsas A. Pubic bone osteomyelitis outcomes in patients with malignancies: A case series from an academic cancer center. J Bone Jt Infect 2025;10:571-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]