Awareness of osteochondroma in atypical sites such as the calcaneum helps avoid diagnostic delay and facilitates definitive surgical management.

Dr. Shreyas Zad, Department of Orthopaedics, Government Medical College and Hospital, Nagpur, Maharashtra, India. E-mail: zad.shreyas97@gmail.com

Introduction: Osteochondroma is the most common benign bone tumor, but its occurrence in the calcaneum is extremely rare. Delayed diagnosis is common due to its atypical location.

Case Report: We report a 19‑year‑old male student who presented with a 2‑year history of bony hard swelling, pain, and discomfort on walking over the inferomedial aspect of the right heel. On examination, there was a 5 × 5 cm bony hard swelling, non‑tender, non‑mobile, with intact overlying skin and no joint restriction. Radiography, computed tomography, and magnetic resonance imaging demonstrated a pedunculated lesion measuring 4.3 × 3.5 × 2.8 cm arising from the calcaneum, with cortex–medullary continuity and a cartilage cap thickness of 4.9 mm. The lesion was excised through a medial approach, and intraoperatively measured 4.5 × 3.5 × 3.0 cm. Histopathology confirmed osteochondroma. The post-operative course was uneventful; full weight-bearing was achieved by 4 weeks. At 6-month follow‑up, the patient remained asymptomatic, fully functional, and with no evidence of recurrence.

Conclusion: Osteochondroma of the calcaneum is rare, but should be considered in the differential diagnosis of chronic heel swelling and pain. Complete surgical excision yields an excellent outcome with minimal recurrence risk.

Keywords: Calcaneum, osteochondroma, benign bone tumor, excision

Osteochondroma, also called osteocartilaginous exostosis, is the most common benign bone tumor, accounting for approximately 20–50% of all benign osseous lesions [1]. It usually presents during the first and second decades of life. It is thought to arise from a defect in the perichondral ring, leading to abnormal cartilage growth that subsequently ossifies [2]. Most osteochondromas occur as solitary lesions, although up to 15% of patients may have multiple lesions as part of hereditary multiple exostoses, an autosomal dominant disorder [3]. Solitary lesions are often detected incidentally, but may become symptomatic depending on their size, location, and relationship to nearby structures [1,2]. Osteochondromas most commonly arise from the metaphyseal regions of long bones such as the distal femur, proximal tibia, and proximal humerus [1,2]. Foot and ankle involvement is rare, representing <10% of cases [4]. Among these, the calcaneum is an especially unusual site, with only isolated case reports available in the literature [5,6,7,8,9]. Due to its rarity, the diagnosis is often delayed or initially mistaken for more common heel pathologies such as plantar fasciitis, calcaneal spur, Haglund’s deformity, or benign cystic lesions [10]. This can lead to prolonged morbidity and functional impairment in affected patients. Radiological evaluation plays a crucial role in establishing the diagnosis. Plain radiographs typically demonstrate a sessile or pedunculated outgrowth with continuity of the cortex and medulla with the parent bone [1]. Computed tomography (CT) scans provide detailed anatomical delineation. They are helpful in surgical planning, whereas magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is the modality of choice for assessing the cartilage cap and evaluating surrounding soft tissues [11]. A cartilage cap thickness exceeding 2 cm in adults is considered suspicious for malignant transformation, usually into secondary chondrosarcoma [12]. Although malignant change is rare in solitary osteochondroma (<1%), the risk is higher in patients with multiple hereditary exostoses (5–25%) [3]. Reports of calcaneal osteochondroma from the Indian subcontinent are even rarer, with very few documented cases [9]. Publishing such cases contributes valuable data to the literature, increases awareness among clinicians, and underscores the importance of including this condition in the differential diagnosis of chronic heel pain and swelling in young patients. In this report, we present the case of a 19‑year‑old male with a symptomatic calcaneal osteochondroma managed successfully with surgical excision. This case adds to the limited Indian literature and highlights the need for awareness, accurate imaging, and timely surgical management in such rare presentations.

A 19‑year‑old male student presented with complaints of swelling, pain, and discomfort on walking over his right heel, with onset approximately 2 years prior. There was no preceding history of trauma, constitutional symptoms, or similar swellings elsewhere in the body. Examination revealed a solitary 5 × 5 cm bony hard swelling over the inferomedial aspect of the right calcaneum, non‑tender, non‑mobile, and overlying skin was normal in appearance, without redness, warmth, or ulceration. Movements at the ankle and subtalar joints were preserved. Plain radiographs of the right ankle lateral and calcaneum axial views demonstrated a well-defined pedunculated bony outgrowth arising from the inferomedial surface of the calcaneum, showing cortical and medullary continuity with the parent bone (Fig. 1).

Figure 1: X‑ray of right calcaneum showing pedunculated bony outgrowth.

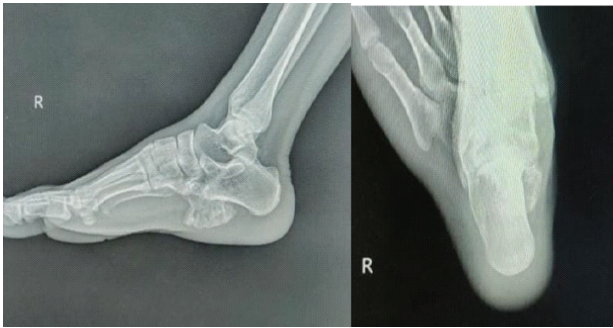

To further delineate the lesion and assess its exact morphology, a CT scan was obtained, which confirmed the pedunculated nature of the lesion, measuring 4.3 × 3.5 × 2.8 cm. MRI of the right ankle was also performed to evaluate the cartilage cap and surrounding soft tissues (Fig. 2).

Figure 2: Computed tomography/magnetic resonance imaging confirming cortex-medullary continuity and cartilage cap.

The lesion was seen to be covered by a cartilage cap measuring 4.9 mm in thickness. No evidence of malignant transformation or soft-tissue invasion was noted.

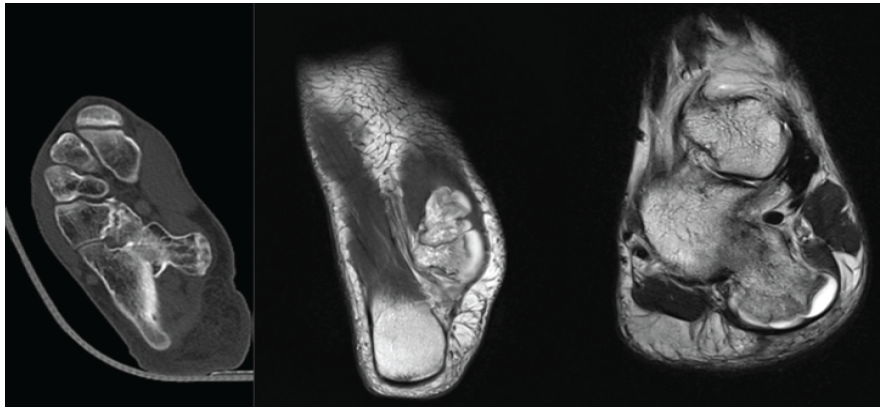

Given the symptomatic nature of the lesion and the progressive discomfort faced in terms of difficulty while walking, surgical excision was planned. Under spinal anesthesia, a medial approach to the calcaneum was utilized. The incision was approximately 6–8 cm and directly centered over the swelling (Fig. 3).

Figure 3: Medial approach to the calcaneum and intraoperative excision using multiple K-wires and osteotome.

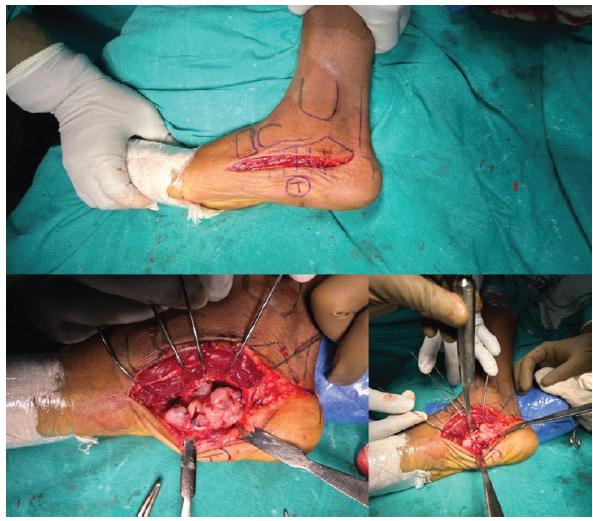

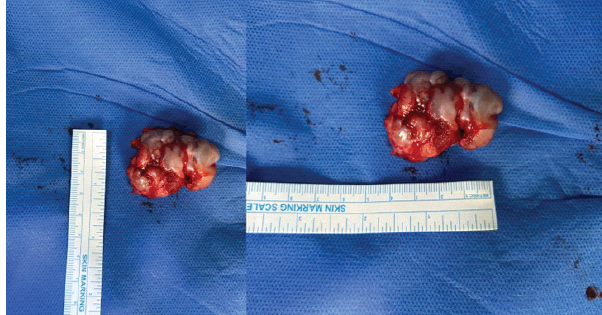

Intraoperatively, during dissection, stretching of the plantar fascia and flexor hallucis brevis was seen. The medial plantar nerve was identified and isolated. This provided adequate exposure to the inferomedial surface of the bone. The lesion appeared as a pedunculated, firm bony projection with a broad stalk. It was carefully excised flush with the underlying cortex by making multiple holes with 2 mm K-wires and interconnected using an osteotome, ensuring complete removal of the cartilaginous cap and stalk (Fig. 4). The excised specimen measured approximately 4.5 × 3.5 × 3.0 cm (Fig. 5). Adequate hemostasis was achieved, bony crater was covered with bone wax to prevent further bleeding from cancellous bone, and the wound was closed in layers over a suction drain.

Figure 4: Excised specimen.

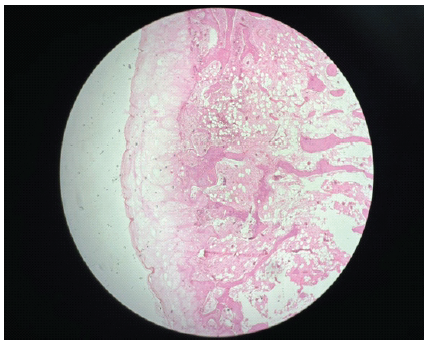

Figure 5: Histopathological slide confirming the osteochondroma.

The excised specimen was sent for histopathological analysis. Microscopic examination revealed trabecular bone with medullary continuity covered by a hyaline cartilage cap without evidence of malignant transformation, confirming the diagnosis of a benign osteochondroma (Fig. 6).

Figure 6: Post-operative 6 months follow-up plain radiographs showing no signs of recurrence.

The post-operative recovery was uneventful, with full weight bearing achieved at 4 weeks. At 6 months follow‑up, the patient was asymptomatic with significant functional improvement and showed no recurrence clinically as well as radiologically (Fig. 6).

Calcaneal osteochondroma remains an unusual diagnosis within the broad spectrum of benign bone tumors. Unlike lesions of the long bones, which are frequently discovered incidentally, calcaneal lesions are usually symptomatic due to the mechanical role of the heel in weight bearing, thus demanding surgical attention. This makes calcaneal osteochondroma an important diagnostic consideration in young patients presenting with persistent heel pain and swelling. The literature on calcaneal osteochondroma is sparse. Blitz and Lopez [5] reported a giant solitary osteochondroma of the inferior medial calcaneal tubercle in a middle-aged male, emphasizing the rarity of such a location. Nogier et al. [6] described an enlarging calcaneal osteochondroma in an adult, raising concern for malignant transformation, although histopathology remained benign. Koplay et al. [7] presented a case of recurrent calcaneal osteochondroma in a skeletally mature patient, which, despite regrowth, did not show malignant change. In addition to osteochondroma, the calcaneum can host other rare, benign, and soft‑tissue tumors that mimic its presentation. Case reports exist of soft‑tissue osteochondromas in the heel pad presenting as firm swellings [13], as well as benign entities such as intraosseous lipoma or unicameral bone cysts that may radiologically resemble exostoses [14]. These differentials reinforce the need for advanced imaging. MRI, in particular, is invaluable for characterizing the cartilage cap, looking for malignant changes, and differentiating such lesions [11,12]. Avramidis et al. [8] recently published a rare case of massive growth after maturity, further emphasizing the unpredictable behavior and varied presentation of osteochondroma. Histopathological examination remains the gold standard, confirming the diagnosis by demonstrating a hyaline cartilage cap with underlying trabecular bone [8].

Asymptomatic lesions may be observed, but when symptoms interfere with daily activities, as in our case, surgery is the treatment of choice [12]. Indications for surgery include pain, restriction of footwear, progressive swelling, or neurovascular compromise. In this patient, the pedunculated lesion caused chronic discomfort and difficulty in shoe wear, warranting surgical excision. The outcome was favorable with no recurrence at 6 months. Recurrence of osteochondroma is rare after skeletal maturity, but it has been reported, particularly in cases where excision was incomplete [7]. Thus, meticulous surgical technique, removing the lesion flush with the cortex and ensuring excision of the cartilaginous cap, is essential to reduce recurrence risk [6].

While osteochondroma is a common benign tumor overall, its occurrence in the calcaneum remains rare and thus should not be overlooked in young adults with persistent heel swelling. These tumors can mimic other pathologies but usually have excellent outcomes after excision. Raising awareness of such presentations will aid clinicians in timely recognition and appropriate management. Complete excision provides an excellent functional outcome and low recurrence.

Osteochondroma, though benign, may present in unusual locations like the calcaneum. Awareness of this rare presentation helps in early diagnosis and effective management.

References

- 1. Kitsoulis P, Galani V, Stefanaki K, Paraskevas G, Karatzias G, Agnantis NJ, et al. Osteochondromas: Review of the clinical, radiological and pathological features. In Vivo 2008;22:633-46. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 2. Unni KK. Dahlin’s Bone Tumors: General Aspects and Data on 11,087 Cases. 5th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott-Raven; 1996. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 3. Schmale GA, Conrad EU 3rd, Raskind WH. The natural history of hereditary multiple exostoses. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1994;76:986-92. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 4. Murphey MD, Choi JJ, Kransdorf MJ, Flemming DJ, Gannon FH. Imaging of osteochondroma: Variants and complications with radiologic-pathologic correlation. Radiographics 2000;20:1407-34. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 5. Blitz NM, Lopez KT. Giant solitary osteochondroma of the inferior medial calcaneal tubercle: A case report and review of the literature. J Foot Ankle Surg 2008;47:206-12. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 6. Nogier A, De Pinieux G, Hottya G, Anract P. Case reports: Enlargement of a calcaneal osteochondroma after skeletal maturity. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2006;447:260-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 7. Koplay M, Toker S, Sahin L, Kilincoglu V. A calcaneal osteochondroma with recurrence in a skeletally mature patient: A case report. Cases J 2009;2:7013. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 8. Avramidis K, Katounis C, Krikis P, Skoufogiannis P. A solitary, large calcaneal osteochondroma growing extensively after skeletal maturity: A case report and review of the literature. Cureus 2023;15:e42570. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 9. Patnala AK, Babu ME, Naidu MC, Kumar SS, Kumar PV. Osteochondroma of the OsCalcaneum – a case report. J Clin Diagn Res 2013;7:1737-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 10. Kumar S, Suresh S. Osteochondroma of calcaneum: A rare cause of heel pain. Foot Ankle Spec 2015;8:153-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 11. Pierz KA, Womer RB, Dormans JP. Malignant transformation of osteochondroma to chondrosarcoma: Incidence and natural history. J Pediatr Orthop 2001;21:604-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 12. Ahmed AR. Malignant transformation of solitary osteochondroma: A case report and review of literature. Cases J 2009;2:7796. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 13. Singh R, Jain M, Siwach RC, Sen R, Rohilla RK, Kaur K. Soft‑tissue osteochondroma of the heel pad: A case report and review of literature. Foot Ankle Surg 2010;16:e76-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 14. Milgram JW. Intraosseous lipomas: Radiologic and pathologic manifestations. Radiology 1988;167:155‑60. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]