Early immersive VR rehabilitation may safely enhance neurological and functional recovery in acute cervical spinal cord injury.

Dr. Takeru Akabane, Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, Yamagata University Faculty of Medicine, Yamagata, Japan/Department of Rehabilitation, Yamagata University Faculty of Medicine, Yamagata, Japan. E-mail: banebanebane73@yahoo.co.jp

Introduction: Virtual reality (VR) rehabilitation has recently been introduced as an innovative rehabilitation technique combining interactive environments with intensive exercise training. This technology has demonstrated benefits in conditions such as stroke and neurodegenerative diseases. However, evidence regarding the application in spinal cord injury (SCI) remains unclear. Early intervention with VR rehabilitation for SCI may promote spontaneous movement and assist recovery with minimal physical burden. We report a case of cervical cord injury in which VR rehabilitation using mediVR KAGURA® was initiated in the acute phase after injury and resulted in excellent recovery.

Case Report: The patient was a 75-year-old male. He sustained a cervical cord injury following a bicycle accident (Frankel grade C1). X-ray and magnetic resonance imaging revealed instability at the C3/4 level and intramedullary signal changes in his cervical spine. He underwent posterior fixation surgery on the day of injury. Stabilization of his cervical spine was achieved, but he suffered from severe muscle weakness, sensory impairment, and marked trunk ataxia. VR rehabilitation using mediVR KAGURA® was started under the supervision of a physical therapist from 1 week postoperatively. The rehabilitation using mediVR KAGURA® was carried out 2–3 times/week, for 20–30 min/day. He performed the program in a sitting position, which encourages active use of the upper limbs and trunk, providing multisensory feedback. He achieved independent sitting within 1 week of starting rehabilitation using mediVR KAGURA® and was able to walk with a walker by the 2nd week. He achieved independence in activities of daily living by 4 months postoperatively, and he was discharged home. At 1 year postoperatively, he had slight residual numbness in the fingertips but lives without any limitations in daily activities. No adverse events occurred during the course of treatment.

Conclusion: This case demonstrated that VR rehabilitation using mediVR KAGURA® could be performed safely and effectively in a patient with cervical cord injury. Early initiation of rehabilitation with mediVR KAGURA® may facilitate voluntary limb activity and enhance functional recovery.

Keywords: Virtual reality, rehabilitation, spinal cord injury, mediVR KAGURA®, somato-cognitive coordination therapy.

In recent years, rehabilitation using robots and virtual reality (VR) has emerged. VR is a category of extended reality (XR) and is defined as “an immersive, completely artificial computer-simulated image and environment with real-time interaction” [1]. XR includes augmented reality and mixed reality in addition to VR. With the recent wave of digital transformation, these technological advances are strongly influencing medical treatment [2]. Among these, immersive VR rehabilitation has been reported to increase the use of the paralyzed limb and promote functional improvement (dose-dependent principle) [3,4]. This was reported to be achieved by blocking the senses, such as vision, from the surrounding environment, and many cases of rehabilitation using immersive VR were reported [5]. Few studies have reported VR rehabilitation for the treatment of acute to subacute spinal cord injury (SCI), such as the improvement of balance and gait function in patients with SCI [6,7]. mediVR KAGURA® (KAGURA, mediVR, Toyonaka City, Japan) has been reported to enhance the therapeutic effects of rehabilitation through somato-cognitive coordination therapy (SCCT), which is described as a therapeutic intervention targeting the somato-cognitive action network (SCAN) as reported by Gordon et al. in 2023 [8,9]. This SCAN is described as an area within the primary motor cortex that controls coordinated motor functions, existing between functional areas such as the hands, feet, and mouth [9]. It has been reported that improving abnormalities in this area (entangled-SCAN) can improve postural instability and gait disorders [8]. SCCT represents a unique therapeutic approach that KAGURA employs in VR rehabilitation. SCCT facilitates the integration of intertwined SCAN in the brain by requiring patients to visualize the overlap of a part of themselves and a target in the VR space and integrating visual, auditory, and tactile feedback to the brain when the objective is achieved [10]. Given the effects of immersive VR rehabilitation as described above, VR rehabilitation was initiated using KAGURA at our facility in 2023. Although the efficacy of KAGURA has been documented for patients with neurodegenerative diseases such as Parkinson’s and Huntington’s disease and cerebrovascular disorders [8,10,11], no studies have reported acute to subacute SCI. However, even in cases of acute SCI in which the general condition is a concern, VR rehabilitation is one of the rehabilitation options that can be employed without a significant physical workload, and rehabilitation may be started earlier in the acute phase. Therefore, this article presents our experience and discussion of the thesis on VR treatment with KAGURA for acute to subacute SCI.

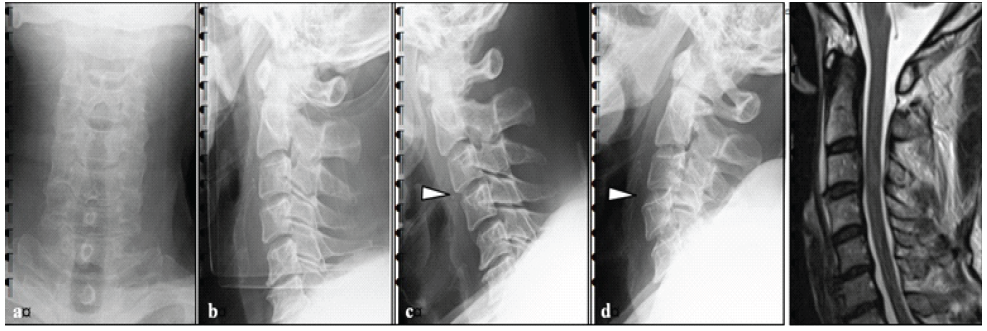

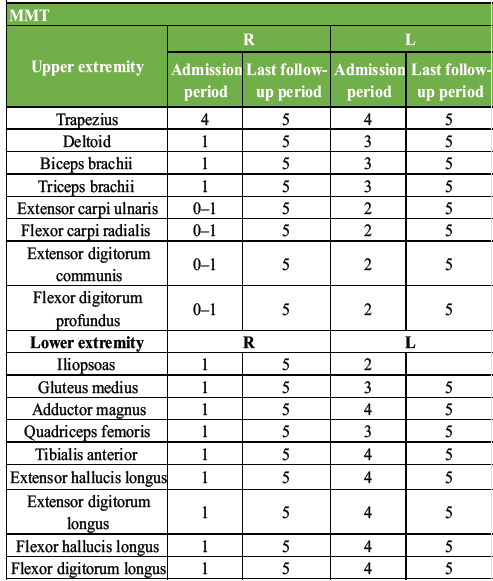

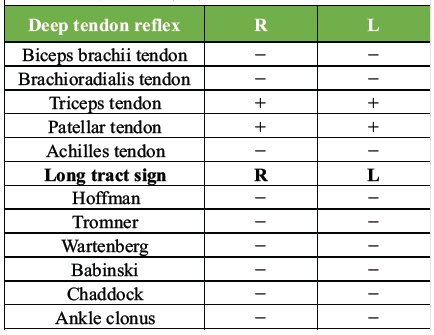

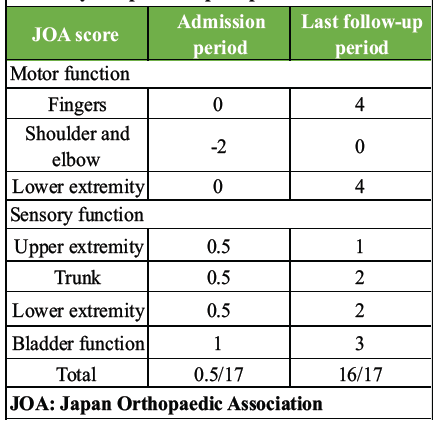

The patient was a 75-year-old male with no previous medical history. He fell off his bicycle while riding. He bruised his forehead and subsequently experienced neck pain and tetraplegia. Therefore, he was transported to a hospital by ambulance. X-ray imaging showed instability in the intervertebral space of the third/fourth cervical vertebrae (C3/4). Magnetic resonance imaging showed a T2 high-signal intensity area within the spinal cord at the C3/4 level (Fig. 1). He had severe muscle weakness and sensory disturbance, particularly on the right side (Table 1). No abnormal reflexes, such as deep tendon hyperreflexia or Babinski reflex, were noted (Table 2). The Japan Orthopaedic Association (JOA) score, which assesses physical dysfunction and the severity of myelopathy [12], was 1.5/17 points (Table 3). He was diagnosed with a cervical SCI (American Spinal Injury Association [ASIA] impairment scale C, Frankel grade C1) with C3/4 disc injury.

Figure 1: Pre-operative imaging findings. (a and b) There was no obvious vertebral fracture, but mild swelling of the retropharyngeal space. (c and d) Flexion and extension imaging of the cervical spine showed C3/4 instability. (e) MRI imaging showed a T2 high signal of the spinal cord on the C3/4 disc level.

Table 1: Physical findings at admission and 1 year after injury. Post-operative MMT improved obviously compared to pre-operative

Table 2: Physical findings at the initial examination. Deep tendon reflexes were absent in the C5 segment immediately after injury

Table 3: JOA score at admission and 1 year after injury. Post-operative JOA scores improved obviously compared to pre-operative scores

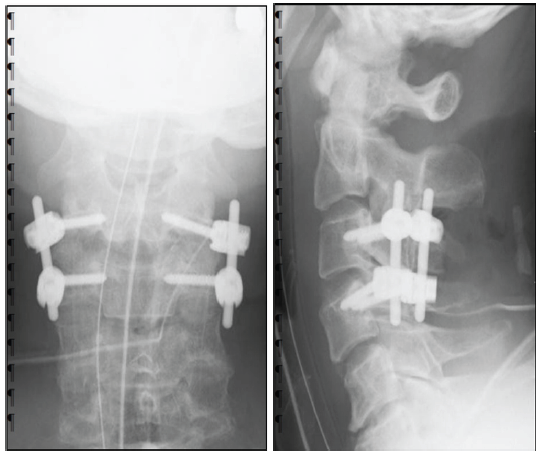

He underwent cervical posterior spinal fusion (C3/4) on the same day. Fig. 2 shows post-operative images. He was released from bed confinement with full assistance on post-operative day 2; however, he had severe ataxia and difficulty in standing with assistance. Therefore, VR rehabilitation using KAGURA, which can be performed in a sitting position with assistance, was started 1 week postoperatively. The use of KAGURA is presented in the figure (Fig. 3). Fig. 3a shows KAGURA being used by a physical therapist at our hospital, which differs not from actual patient use. The patient sat on a chair with a backrest and underwent rehabilitation. When significant trunk instability caused a risk of falling, a chair with armrests was used. One physical therapist attended, fitting a head-mounted display to the patient’s head and having them grip controllers in both hands (Fig. 3b). When gripping was difficult, the patient’s hand and controller were held with a belt, enabling them to grip the controller. There are five games built into KAGURA. In this case, two games were used: One was “a game for reaching out to targets,” and the other was “a game for catching balls falling from the sky,” both designed to be easily understood by elderly players (Fig. 3c and d). During periods of severe motor paralysis, the physical therapist assisted the patient while the game was being played. These interventions were carried out for 20–30 min/day, 2–3 times/week, depending on the patient’s condition.

Figure 2: Post-operative X-ray image of the cervical spine. C3/4 was fixed using a pedicle screw, and stability was achieved. (a) Anteroposterior view of the cervical spine. (b) lateral view of the cervical spine.

Figure 3: Images of rehabilitation with KAGURA. (a and b) Demonstration of virtual reality-guided training by a physical therapist. (c and d) In the 3D virtual space, the user catches red or blue falling objects or touches targets with a right- or left-hand controller. These tasks are presented in a video game style.

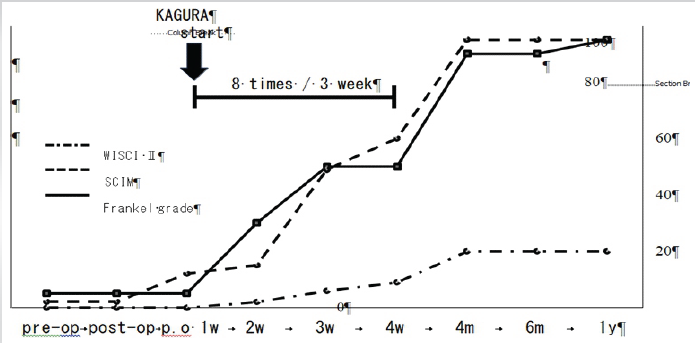

Before the rehabilitation, his activities of daily living (ADLs) were 0 points in the walking index for SCI (WISCI) II evaluation and 2 points in the spinal cord independence measure (SCIM) evaluation. 1 week after the start of rehabilitation with KAGURA (2 weeks postoperatively), he was able to maintain a sitting position independently. Another week later, he was able to practice walking. 3 weeks after the start of the KAGURA rehabilitation, he was able to walk independently using a walker and was transferred to another hospital. Between 1 and 4 weeks postoperatively, rehabilitation with KAGURA was performed 8 times. At the time of the hospital transfer, his physical function had improved to ASIA impairment scale D and Frankel grade D1, and ADL had improved to 10 points on the WISCI II and 60 points on the SCIM. In this case, rehabilitation with KAGURA did not cause complications.

Four months postoperatively, the patient achieved fully independent ADLs and was discharged home. At the 6-month follow-up, his JOA score was 14/17, indicating an improvement in his condition, with ASIA impairment scale D, Frankel grade D3, 20 points on WISCI II, and 100 points on the SCIM. At the 1 year follow-up, his condition had further improved, with a JOA score of 16/17, ASIA disability classification D, and Frankel classification E. The WISCI II score and SCIM score remained at full points (Fig. 4, Tables 1 and 3).

Figure 4: The course of walking index for spinal cord injury II, spinal cord independence measure, Frankel grade. Improvement in activities of daily living has been observed since the start of rehabilitation with KAGURA.

The severity at the time of injury is important for the prognosis of SCI. In the case of cervical cord injury, approximately 70% of patients with grade C, as proposed in the ASIA, achieved the ability to walk [13]. However, in this classification, grade C is a broad assessment of severity. A detailed study using the modified Frankel classification reported that 36% of Frankel grade C1 cases could walk outdoors after more than 6 months of follow-up [14]. In light of this finding, VR rehabilitation could potentially improve the walking ability of the presented patient. To our knowledge, no studies have described the extent of improvement in neurological symptoms in a shorter period after injury, such as weekly or monthly intervals. Consequently, although the patient may have been able to walk without VR rehabilitation, the early intervention of VR rehabilitation may have contributed to the early achievement of walking ability. Some researchers have reported that VR rehabilitation for SCI has been reported. For example, VR rehabilitation with Nintendo™ Wii Fit was reported to significantly improve gait speed and trunk balance in patients with SCI [15]. In addition, SCCT with KAGURA was reported to improve postural stability and gait disorders such as disuse syndrome [16], and more recently, it has been reported to improve static or dynamic postural stability for persistent sensorineural posture-induced vertigo [17]. However, no studies have reported rehabilitation using KAGURA for acute to subacute SCI, with only case reports of its use in patients with spinal cord infarction in the chronic phase of the disease [18]. In this case, VR rehabilitation for SCI during the acute to subacute phase could be conducted to restore neurological function without complications. In recent years, studies have reported treatment with Hybrid Assisted Limb® (HAL) in robotic rehabilitation. Its therapeutic effects have been reported in acute to chronic phases of SCI [19,20,21]. An interactive biofeedback system has been proposed as the main mechanism of HAL treatment [21]. However, the effects of KAGURA on the spinal cord are still unclear, since it is assumed to affect the cranial nerves, such as vision and hearing. However, some cases have been reported in which the use of KAGURA for SCI resulted in symptomatic improvement, suggesting the possibility of neural redistribution through spinal reflex pathways or plastic changes within the central nervous system [22]. For motor impairments caused by stroke or disuse syndrome, an immersive VR environment improves attention and cognition, and sitting exercises improve balance. This effect has been reported to improve walking ability and ataxia [11,16]. Although this mechanism differs from that of HAL, the effort to move the limb may influence the brain and achieve rehabilitation based on the SCCT principles to resolve the tangle. We are currently considering the use of KAGURA for patients who cannot maintain a standing position due to severe ataxia or who experience difficulty standing because of circulatory effects. At our hospital, we view this to be a difference from HAL’s indications, which primarily focus on rehabilitation in a standing position. Although further studies are needed, HAL, which mainly offers full-body exercise, is anticipated to cause greater physical exertion than KAGURA. Consequently, it may be feasible to start rehabilitation with KAGURA in cases at risk of circulatory effects and subsequently transition to rehabilitation with HAL as the patient’s tolerance for physical exertion improves. In any case, KAGURA, which is presumed to be able to initiate rehabilitation with low physical exertion, is expected to provide rehabilitation intervention at an earlier phase. In this case, compared with conventional therapy for the paralyzed limbs following SCI, patients make more effort to move their limbs by themselves and feel more fatigue after the rehabilitation. Thus, this may be a medical treatment that achieves the “dose-dependent” concept, which is important in acute-phase rehabilitation. Early intervention in immersive VR rehabilitation may increase the use of the paralyzed limb and promote functional improvement without complications. This study has some limitations. First, as this is a case report, increasing the number of cases and reconsidering the results of the use of the KAGURA are crucial. However, we believe that this study will help promote rehabilitation with the patient’s motivation, if the patient’s general condition is at least stable, and if the patient can maintain a sitting position with assistance. Second, no comparative data are available because this is a case report. Thus, prospective studies including multicenters and large populations may help further demonstrate the usefulness of VR rehabilitation. Finally, the mechanism by which SCCT affects the spinal cord remains unclear. While accumulating evidence for the therapeutic efficacy of KAGURA, it is considered necessary to elucidate the mechanism of SCCT’s therapeutic effect for the spinal cord through basic research in the future.

This case study suggests that immersive VR rehabilitation using KAGURA can be safely performed during the acute to subacute phase of cervical cord injury and may promote earlier functional recovery. Although further research using large cohorts and analysis of the mechanisms for the therapeutic effect on the spinal cord are required, early intervention of VR rehabilitation using SCCT holds the potential to enhance patient motivation, promote the use of paralyzed limbs, and lead to dose-dependent neurological and functional improvements.

VR rehabilitation can increase the use of the limb suffering from motor paralysis, promote the ‘‘dose-dependent principle’’ and facilitate functional improvement. VR rehabilitation for acute to subacute SCI may improve neurological function, in addition to recovery in the natural course of the injury.

References

- 1. Morimoto T, Hirata H, Ueno M, Fukumori N, Sakai T, Sugimoto M, et al. Digital transformation will change medical education and rehabilitation in spine surgery. Medicina (Kaunas) 2022;58:508. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 2. Morimoto T, Kobayashi T, Hirata H, Otani K, Sugimoto M, Tsukamoto M, et al. XR (extended reality: Virtual reality, augmented reality, mixed reality) technology in spine medicine: Status Quo and QuoVadis. J Clin Med 2022;11:470. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 3. Ase H, Honaga K, Tani M, Takakura T, Wada F, Murakami Y, et al. Effects of home-based virtual reality upper extremity rehabilitation in persons with chronic stroke: A randomized controlled trial. J Neuroeng Rehabil 2025;22:20. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 4. Schweighofer N, Han CE, Wolf SL, Arbib MA, Winstein CJ. A functional threshold for long-term use of hand and arm function can be determined: Predictions from a computational model and supporting data from the Extremity Constraint-Induced Therapy Evaluation (EXCITE) Trial. Phys Ther 2009;89:1327-36. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 5. Kiper P, Godart N, Cavalier M, Berard C, Cieślik B, Federico S, et al. Effects of immersive virtual reality on upper-extremity stroke rehabilitation: A systematic review with meta-analysis. J Clin Med 2023;13:146. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 6. Miguel-Rubio A, Rubio MD, Salazar A, Moral-Munoz JA, Requena F, Camacho R, et al. Is virtual reality effective for balance recovery in patients with spinal cord injury? A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Med 2020;9:2861. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 7. Abou L, Malala VD, Yarnot R, Alluri A, Rice LA. Effects of virtual reality therapy on gait and balance among individuals with spinal cord injury: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurorehabil Neural Repair 2020;34:375-88. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 8. Hara M, Murakawa Y, Wagatsuma T, Shinmoto K, Tamaki M. Feasibility of somato-cognitive coordination therapy using virtual reality for patients with advanced severe Parkinson’s disease. J Parkinsons Dis 2024;14:895-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 9. Gordon EM, Chauvin RJ, Van AN, Rajesh A, Nielsen A, Newbold DJ, et al. A somato-cognitive action network alternates with effector regions in motor cortex. Nature 2023;617:351-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 10. Shinmoto K, Torikai Y, Hara M. Impact of somato-cognitive coordination therapy on activities of daily living in a patient with Huntington’s disease. BMJ Case Rep 2024;17:e262695. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 11. Takimoto K, Omon K, Murakawa Y, Ishikawa H. Case of cerebellar ataxia successfully treated by virtual reality-guided rehabilitation. BMJ Case Rep 2021;14:e242287. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 12. Yonenobu K, Abumi K, Nagata K, Taketomi E, Ueyama K. Interobserver and intraobserver reliability of the japanese orthopaedic association scoring system for evaluation of cervical compression myelopathy. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2001;26:1890-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 13. Khorasanizadeh M, Yousefifard M, Eskian M, Lu Y, Chalangari M, Harrop JS, et al. Neurological recovery following traumatic spinal cord injury: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Neurosurg Spine 2019;30:683-99. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 14. Fukuda F, Ueta T. Prediction of prognosis using modified Frankel classification in cervical spinal cord injured patients. Jpn J Rehabil Med 2001;38:29-33. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 15. Wall T, Feinn R, Chui K, Cheng MS. The effects of the Nintendo™ Wii Fit on gait, balance, and quality of life in individuals with incomplete spinal cord injury. J Spinal Cord Med 2015;38:777-83. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 16. Omon K, Hara M, Ishikawa H. Virtual reality-guided, dual-task, body trunk balance training in the sitting position improved walking ability without improving leg strength. Prog Rehabil Med 2019;4:20190011. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 17. Yamaguchi T, Miwa T, Tamura K, Inoue F, Umezawa N, Maetani T, et al. Temporal virtual reality-guided, dual-task, trunk balance training in a sitting position improves persistent postural-perceptual dizziness: Proof of concept. J Neuroeng Rehabil 2022;19:92. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 18. Michibata A, Haraguchi M, Murakawa Y, Ishikawa H. Electrical stimulation and virtual reality-guided balance training for managing paraplegia and trunk dysfunction due to spinal cord infarction. BMJ Case Rep 2022;15:e244091. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 19. Zieriacks A, Aach M, Brinkemper A, Koller D, Schildhauer TA, Grasmücke D. Rehabilitation of acute vs. Chronic patients with spinal cord injury with a neurologically controlled hybrid assistive limb exoskeleton: Is there a difference in outcome? Front Neurorobot 2021;15:728327. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 20. Soma Y, Kubota S, Kadone H, Shimizu Y, Takahashi H, Hada Y, et al. Hybrid assistive limb functional treatment for a patient with chronic incomplete cervical spinal cord injury. Int Med Case Rep J 2021;14:413-20. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 21. Kubota S, Abe T, Kadone H, Shimizu Y, Funayama T, Watanabe H, et al. Hybrid assistive limb (HAL) treatment for patients with severe thoracic myelopathy due to ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament (OPLL) in the postoperative acute/subacute phase: A clinical trial. J Spinal Cord Med 2019;42:517-25. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 22. Murakawa Y, Shinmoto K, Hara M. Applications of somato-cognitive coordination therapy using virtual reality technology. Orthop Surg Traumatol 2024;67:1483-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]