This study highlights that zero-profile cervical implants represent an effective evolution in anterior cervical fusion techniques, demonstrating that implant design plays a crucial role in minimizing approach-related complications while maintaining satisfactory radiological fusion and functional recovery in single-level.

Dr. SK Mizanur Rahaman, Department of Orthopaedics, R G Kar Medical College and Hospital, Kolkata, West Bengal, India. E-mail: skmizanur29@gmail.com

Introduction: Anterior cervical discectomy and fusion for single-level degenerative disc prolapse with myelopathy has been traditionally instrumented with an anterior cervical plate with a cage. However, as it has been associated with multiple complications, Zero-profile implants with locking screws have recently been used. The purpose of this study was to analyse the clinical and radiological outcome of Zero-profile devices in treating single-level cervical spondylotic myelopathy in the Indian scenario.

Materials and Methods: In this prospective study, 30 patients have been treated by using two types of zero-profile implant: polyetheretherketone (PEEK) and Titanium. Apart from the per-operative parameters, both radiological and functional parameters (Japanese Orthopedic Association [JOA] and Neck Disability Index [NDI]) have been assessed at regular intervals up to a mean follow-up of 1 year. Complications related to the procedures have been documented and taken care of.

Results: Mean operative time was 65 ± 18 min, mean blood loss 60 ± 12 mL. The Cobb angle was significantly improved. Fusion with both types of implant was noted in around 75% cases at the end of 1 year. Subsidence was noted with PEEK implant in 25% cases. Disturbance of pre-vertebral soft tissue was minimum, which was reflected as only 26% cases of mild dysphagia at the end of 2 weeks. Both JOA score and NDI score improved significantly at the end of 1 year. No major complications were encountered.

Conclusion: Zero-profile implants prove to be effective in the treatment of single-level cervical myelopathy due to their biomechanical stability, ability to restore radiological parameters, and capacity to provide long-term functional improvement. Level of Evidence: III

Keywords: Cervical myelopathy, anterior cervical discectomy and fusion, zero-profile implant, zero-p.

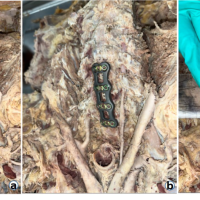

Since its first use in 1958 [1], anterior cervical discectomy and fusion (ACDF) has become the standard surgical procedure for managing single or multiple levels of degenerative cervical spondylosis, particularly in patients with herniated cervical intervertebral discs [2,3] The implementation of the anterior plating system aimed to provide greater stability in the period immediately following bone grafting between vertebral bodies. This technique offers several advantages, including better sagittal alignment, prevention of graft displacement, and improved fusion rates and spinal stability [4,5]. However, the use of anterior cervical plates is not without risks, as it has been linked to complications, such as increased rates of dysphagia, injury to the trachea and esophagus, and degeneration of adjacent spinal segments [6,7,8,9]. To reduce the risk of complications while preserving the advantages of anterior cervical plating, the zero-profile anchored spacer (Zero-P; Synthes GmbH polyetheretherketone [PEEK], Oberdorf, Switzerland) was specifically designed for patients with degenerative cervical spondylosis (Fig. 1a). More recently, titanium implants featuring similar designs have also been introduced and are currently being used for the same clinical indication.

Figure 1: (a) Photograph showing the Zero‑profile polyetheretherketone device (Synthes, GmbH).

The aim of this study was to evaluate the clinical and radiological outcomes of Zero-profile devices in the treatment of single-level cervical spondylotic myelopathy (CSM) caused by intervertebral disc prolapse and resulting neural compression, specifically within the Indian patient population.

Ethics statement, patient anonymity, and informed consent

This study was approved by the institutional review board of Our Hospital (CZ-2015-N016). All subjects provided written informed consent. Research was conducted in accordance with the research principles mentioned in the Declaration of Helsinki.

Patient population

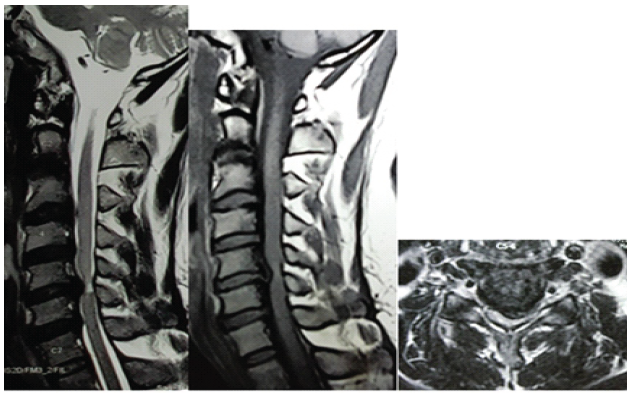

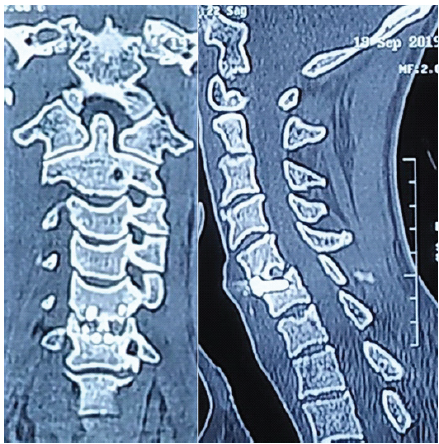

A prospective study was carried out involving 30 patients who presented to our institution between January 2020 and November 2022. Patients with classical symptoms and signs of degenerative CSM with radiological signs of single-level cervical disc prolapse causing cord compression with hyper-intensity signal at T2 ± T1 sequence were selected for this study (Fig. 2a, b and c).

Figure 2: (a-c) Sagittal T2 and T1 and axial T2 image showing C5-6 postero-central prolapsed disc producing hyperintensity signal at T2 sequence.

All of these patients had failed to respond toward conservative treatment for at-least 6 months. Patients with predominant axial and/or radicular symptoms, associated cervical fractures, tumor, ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament, ossification of the ligamentum flavum and a history of past cervical surgery were excluded from the study. Patients who needed simultaneous anterior and posterior surgery for CSM were also excluded.

Surgical techniques

For ACDF procedures utilizing the Zero-Profile implant, patients were positioned supine under general anesthesia. Fluoroscopy was used to accurately identify and confirm the target cervical level. A horizontal incision was then made along the natural skin crease corresponding to the targeted disc level. Following the removal of the intervertebral disc and meticulous preparation of the endplates, thorough decompression of the bilateral neuroforamina was carried out. To relieve nerve root compression, a Kerrison punch and a high-speed electric drill were employed to remove osteophyte overgrowth from the uncovertebral joints and the posterior vertebral body lips. Throughout the drilling and milling process, continuous saline irrigation was maintained to ensure a clear surgical field and to minimize the risk of thermal injury [10]. Following anterior decompression and, if necessary, lesion reduction to restore physiological alignment, trial spacers were used to select the appropriate implant shape. Two types of Zero-Profile implants were utilized by the authors: Type A, the Zero-P (Synthes GmbH, PEEK, Oberdorf, Switzerland), and Type B, a titanium implant with two cephalo-caudal screws. After trial spacer fitting, stabilization was achieved by placing the Zero-Profile implant, with screws inserted under intraoperative fluoroscopic guidance. After releasing the Casper distractor, the stability of the segments was verified using a manual pull-out test. All cages were packed with locally harvested bone grafts and osteophytes. Proper placement of the cage was confirmed with an image intensifier in both lateral and anteroposterior views. Ideally, the device was positioned approximately 2 mm posterior to the anterior column in the lateral view and centered within the disc space in the anteroposterior view. Upon full insertion, the zero-profile characteristic of the Zero-P implant was distinctly visible. The two types of Zero-Profile implants were alternately utilized among the fifteen patients [10]. Post-operatively, all patients were advised to wear a Philadelphia neck brace for 3 weeks. Following this period, supervised passive and active neck mobilization exercises were initiated. Upon discharge, patients were referred to physical medicine departments for appropriate rehabilitation therapy [10,11].

Radiological evaluation

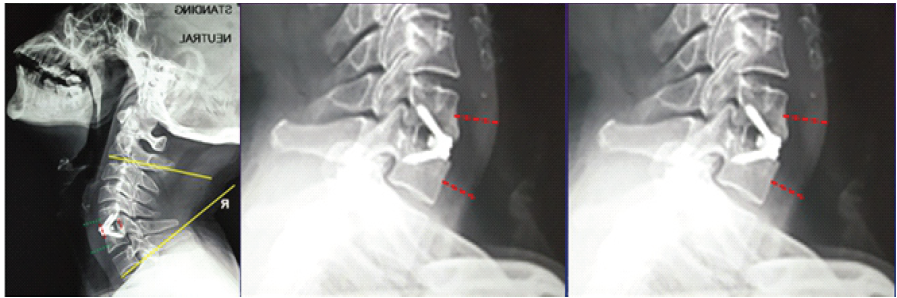

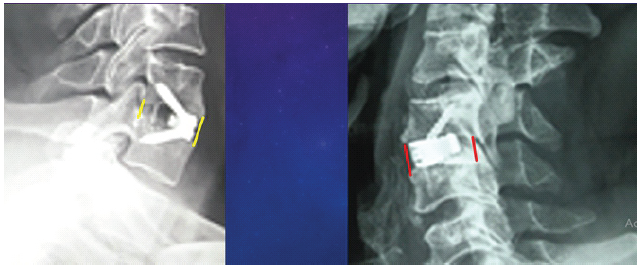

In addition to tracking operative time, intraoperative blood loss (BL), and length of hospital stay, radiological evaluations were conducted pre-operatively, post-operatively, and during follow-ups at roughly 3, 6, and 12 months. These assessments included cervical anteroposterior and lateral X-rays as well as computed tomography (CT) scans of the cervical spine [10]. The cervical Cobb angle was determined by measuring the acute angle formed between lines drawn along the inferior endplates of the C2 and C7 vertebral bodies on a lateral X-ray. The fused segment disc height (FSDH) was calculated as the average of the anterior and posterior disc heights, measured from the lower endplate of the upper vertebra to the upper endplate of the lower vertebra within the fused segment (Fig. 3a) [12].

Figure 3: (a) Cobb angle measuring between the inferior end plates of C2 and C7. Fused segment disc height is the average of the anterior and posterior Red lines.

Fusion assessment was conducted using dynamic cervical X-rays and sagittal CT reconstructions at 12 months post-operatively. Fusion was defined by the following criteria: (1) Interspinous distance changes of no more than 2 mm on lateral flexion-extension radiographs, (2) absence of a radiolucent gap between the cage and the endplate, and (3) presence of continuous bridging bony trabeculae across the intervertebral space [13,14]. Cage subsidence was defined as a reduction in FSDH exceeding 3 mm at 1 year post-surgery compared to the measurement taken 1 month after surgery, reflecting the combined displacement between the superior and inferior vertebral body surfaces adjacent to the cage [14,15]. Pre-vertebral soft tissue thickness was evaluated during the pre-operative assessment, as well as at 2 weeks and 3 months post-surgery. On lateral cervical X-rays, this thickness was assessed by calculating the average distance between the anterior surface of each vertebral body or implant plate and the air shadow of the airway. Screw loosening was identified by the presence of a radiolucent zone >1 mm surrounding the screws on both anteroposterior and lateral plain radiographs [16]. Adjacent segment degeneration (ASD) was defined by the occurrence of anterior osteophyte enlargement or new osteophyte formation, disc height reduction of 30% or more, and segmental instability visible on plain radiographs, or by decreased disc signal intensity and intervertebral herniation at adjacent segments (cranial, caudal, or intermediate) on T2-weighted magnetic resonance imaging scans [17]. The presence and severity of heterotopic ossification (HO) were graded on dynamic lateral radiographs following McAfee’s criteria [6].

Clinical evaluation

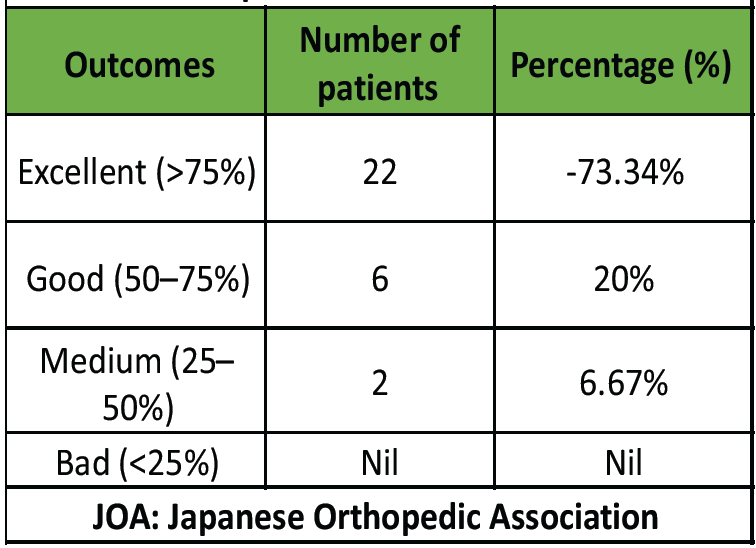

Clinical outcomes were evaluated pre-operatively, post-operatively, and at the final follow-up by utilizing the Neck Disability Index (NDI) and Japanese Orthopedic Association (JOA) scores. The JOA improvement rate (IR) was calculated as ([post-treatment score – pre-treatment score] / [17– pre-treatment score]) × 100%, and categorized as excellent (>75%), good (50–75%), fair (25–50%), or poor (<25%) [18,19]. Post-operative dysphagia rates were evaluated based on the criteria by Bazaz et al. at immediate post-operative day 1, 2 weeks, and 3 months [19]. Dysphagia severity was classified as none, mild, moderate, or severe, according to patient reports. In addition, dysphagia was assessed using the modified Swallowing Quality of Life (SWAL-QOL) questionnaire [20], which all patients completed before surgery and at 2 weeks and 3 months post-operatively.

Statistical analysis

Patient characteristics and clinical outcomes were analyzed descriptively, with quantitative variables presented as mean (standard deviation) and median (interquartile range), and qualitative variables expressed as frequency (percentage). P-values are reported for all findings that reached statistical significance. Statistical analyses were performed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences for Windows, version 19.0 (IBM, Chicago, IL, USA). All statistical tests were two-sided, and a P < 0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance [10,11].

The background characteristics of the patients among the 30 individuals included in the study, the male-to-female ratio was 12:3. The mean age was 55.4 ± 7.2 years, ranging from 52 to 68 years. The most frequently involved vertebral segment was C6/7 (14 cases), followed by C5/6 (10 cases), C4/5 (4 cases), and C3/4 (2 cases). Regarding intraoperative outcomes, the authors encountered no technical difficulties during implantation, except for one case involving the C3/4 level, which required increased soft tissue retraction. The average surgical time was 65 ± 18 min (range 50–100 min), with an estimated average BL of 60 ± 12 mL (range 40–90 mL). The average hospital stay was 4.5 ± 2.4 days. No patients experienced neurological deterioration following surgery. All patients were monitored for at least 1 year, with a mean follow-up duration of 14 months and a range of 12–28 months. Throughout the study, no patients were lost to follow-up.

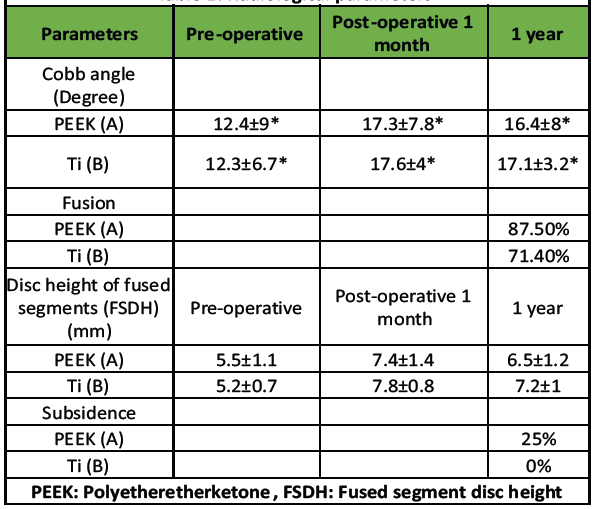

Table 1: Radiological parameters

Regarding radiological outcomes (Table 1), the authors evaluated parameters separately for the two implant types used: Group A (PEEK) and Group B (titanium). In Group A, the mean Cobb angle increased from 12.4 ± 9° pre-operatively to 17.3 ± 7.8° post-operatively, stabilizing at 16.4 ± 8° at 1 year. In Group B, the Cobb angle improved from 12.3 ± 6.7° pre-operatively to 17.6 ± 4° post-operatively, settling at 17.1 ± 3.2° after 1 year. Fusion was achieved in 87.5% of cases in Group A and 71.4% of cases in Group B at the 1-year mark (Fig. 4a and b).

Figure 4: (a and b) computed tomography coronal (a) and sagittal (b) images showing signs of additional new bone formation with bony bridging across the disc space indication of fusion.

The FSDH in Group A increased from 5.5 ± 1.1 mm pre-operatively to 7.4 ± 1.4 mm post-operatively, then settled at 6.5 ± 1.2 mm at 1 year. Similarly, Group B showed an improvement in FSDH from 5.2 ± 0.7 mm pre-operatively to 7.8 ± 0.8 mm post-operatively, stabilizing at 7.2 ± 1 mm at 1 year. Cage subsidence was observed in 2 of 8 cases (25%) in Group A, while no subsidence was noted in Group B (Fig. 5a and b).

Figure 5: (a and b) Polyetheretherketone implant shows signs of subsidence (left) compared with the titanium implant (right).

Concerning pre-vertebral soft tissue thickness, it increased from pre-operative 12.1 ± 3.3 mm to post-operative 14.4 ± 2.6 mm and again decreased to 13 ± 1.2 mm at the end of 3 months.

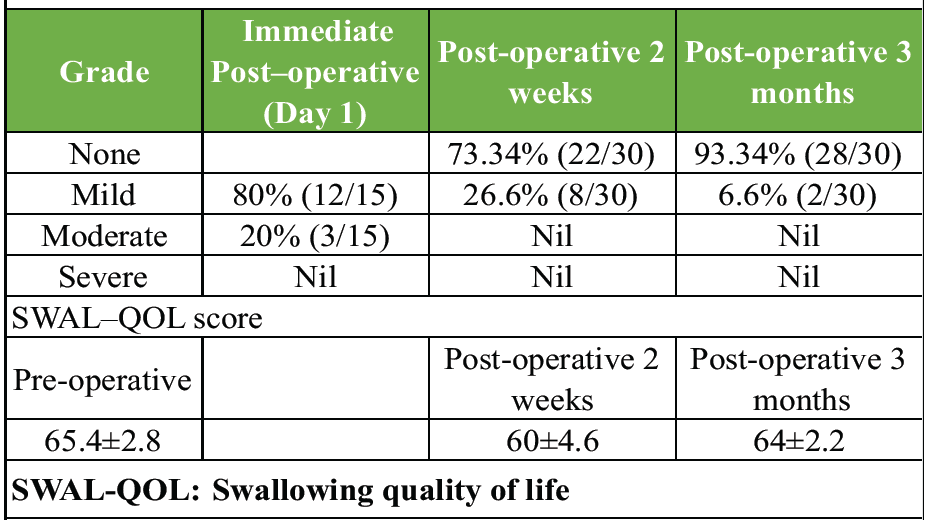

Table 2: Incidence of dysphagia

The incidence of dysphagia (Table 2) on immediate post-operative day 1 was mild in 80% of patients (24/30) and moderate in 20% (6/30). Symptoms improved over the following 2 weeks, with 73.4% of patients (22/30) experiencing complete resolution, while 26.6% (8/30) continued to have mild symptoms. At 3 months post-surgery, only one patient (6.6%) still reported mild dysphagia. Based on the modified SWAL-QOL questionnaire, the pre-operative score averaged 65.4 ± 2.8, decreased to 60 ± 4.6 immediately post-operative, and then improved to 64 ± 2.2 at the 3-month follow-up.

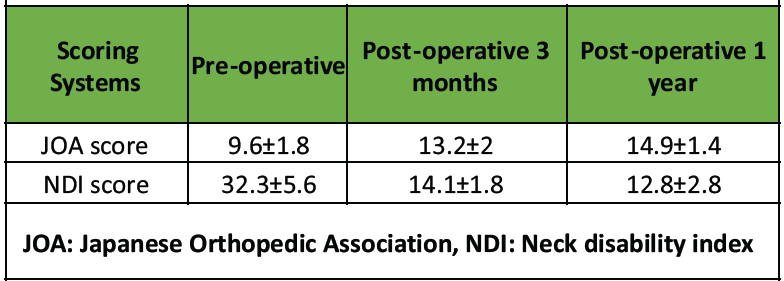

Table 3: Assessment of functional outcome

All patients demonstrated functional improvement through the final follow-up. The mean pre-operative JOA score was 9.6 ± 1.8, which increased to 13.2 ± 2 at 3 months post-operatively and further improved to 14.9 ± 1.4 at 1 year (Table 3). Similarly, the mean pre-operative NDI score of 32.3 ± 5.6 decreased to 14.1 ± 1.8 at 3 months and improved further to 12.8 ± 2.8 at 1 year (Table 3). The JOA IR (Table 4) indicated that 22 patients (73.3%) achieved “Excellent” improvement, 6 patients (20%) had ‘Good’ improvement, and 2 patients (6.7%) showed “Medium” improvement.

Table 4: Improvement ratio of JOA score

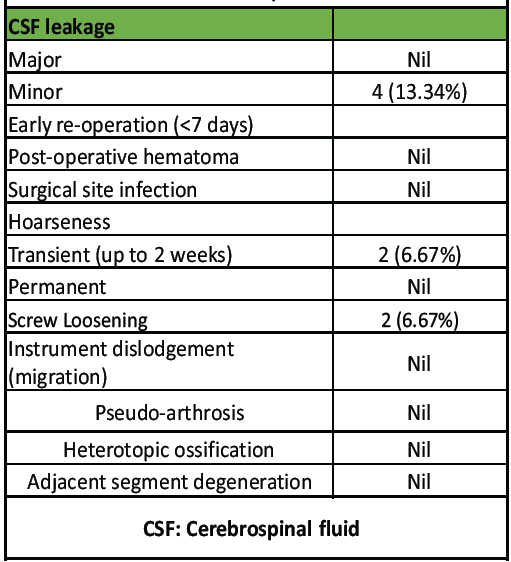

Regarding complications (Table 5), no major cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leaks were observed. Two cases of minor CSF leaks resolved with the use of gel-foam and methylcellulose patties. One patient experienced transient hoarseness of voice, which improved over time.

Table 5: Complications

Radiologically, one case of screw loosening was detected without any clinical consequences. There were no occurrences of post-operative hematoma, surgical site infection requiring reoperation, instrument dislodgement (migration), pseudoarthrosis, HO, or ASD.

Although the use of an anterior cage and plate construct for ACDF in single-level degenerative cervical myelopathy is a well-established surgical technique, it is frequently associated with complications arising from soft tissue injury. In an effort to minimize these potential complications while retaining the benefits of anterior cervical plating, zero-profile implants have been introduced. Biomechanical studies, such as that by Scholz et al. [21], have demonstrated no significant difference in stability between Zero-P implant fixation and traditional titanium plate with cage fixation. In this study, we aimed to evaluate the efficacy and safety of zero-profile implants (both PEEK and titanium) based on radiological and functional outcomes in the treatment of single-level degenerative cervical myelopathy. Regarding intraoperative parameters, the average operating time and BL in our study were comparable to values reported in the literature (BL: Sung et al. [22] 74.4 ± 17 mL; Wang et al. [23] 56.8 ± 19 mL / Operating time: Sung et al. [22] 113.3 ± 19 min; Wang et al. [23] 80 ± 12 min). The simplified procedure, involving only a few steps for cage insertion and a one-step locking mechanism for screw fixation, contributes to reduced operating time and BL, which in turn helps minimize hospital stay duration. Restoration of the Cobb angle was effectively achieved with both PEEK and titanium implants, and this improvement was maintained for up to 1 year. The fusion rate at 1 year was also comparable to that reported in other studies. The disc height of the FSDH showed significant improvement in the early post-operative period in both groups (A and B). However, due to subsidence observed with PEEK implants, the FSDH significantly decreased after 1 year. This may be explained by the fact that the elastic modulus of the PEEK cage closely matches that of normal human cortical bone, which can result in some settling or subsidence after fusion with the endplates in certain cases. To prevent subsidence, careful preservation of the bony endplates, selecting an appropriately sized cage, and avoiding over-distraction are likely important measures [14]. Although a 25% subsidence rate was noted with PEEK implants, it did not significantly affect overall sagittal alignment parameters. To date, no other studies have compared PEEK implants with zero-profile titanium implants regarding these radiological outcomes. Chronic dysphagia is the most common complication following ACDF, with reported incidence rates ranging from 3% to 21% [6,7,8,9]. Factors potentially contributing to post-operative dysphagia include soft tissue swelling, hematoma formation at the surgical site, esophageal injury, duration of surgery, adhesion development around the implant, and implant thickness [24]. Zero-profile implants, due to their smaller size, require a smaller incision, reduced exposure, and less soft tissue retraction, and they are fully contained within the intervertebral disc space, thereby minimizing irritation to surrounding structures. Incidence rates of dysphagia reported in the literature include 14.5% by Son et al. [25], 20% at 2 weeks by Wang et al., [23] and 3.6% at 3 months by Lu et al., [26] In our study, dysphagia incidence was 26% at 2 weeks and 6% at 3 months, aligning with these reports. The SWAL-QOL scores at 2 weeks and 3 months post-operatively in our study were also comparable to those reported by Qizhi et al. [20], who observed scores changing from 68.06 ± 2.11 pre-operatively to 65.64 ± 3.53 post-operatively, then improving to 67.65 ± 2.57 at final follow-up. Our measurements of pre-vertebral soft tissue thickness showed no significant difference between pre-operative and 3-month post-operative values. Therefore, we conclude that the use of Zero-profile implants minimally disrupts pre-vertebral soft tissues, resulting in a lower risk of chronic dysphagia following ACDF. The authors reported a single case of hoarseness and dysphonia, which was managed through aerosol inhalation therapy consisting of Dexamethasone 5 mg combined with Chymotrypsin, along with the use of a humidifier 3 times daily for a duration of 10 days. This treatment ultimately led to an improvement in symptoms within a 2-week period. Furthermore, the functional outcomes, as assessed by the JOA score and the NDI score, demonstrated a statistically significant enhancement at the 1-year post-operative mark. Approximately 75% of the patients exhibited an “Excellent” level of improvement in their myelopathy scores, a result that was consistent and comparable with findings reported in other studies [22,24,25,27]. The authors closely monitored the isolated case involving a single instance of screw loosening; however, this has not resulted in any pressure-related symptoms to date. Matsumoto et al. [28] reported a significantly higher rate of radiographic progression of ASD in patients who underwent ACDF compared to healthy control subjects. It was hypothesized, based on biomechanical studies, that hypermobility and increased stress at the adjacent spinal segments contributed to the development of ASD [29]. The reduction in the range of motion at the fused level is typically compensated for by increased motion at the adjacent levels, which in turn leads to heightened compensatory stress within the adjacent intervertebral discs following fusion [30]. In the present study, the authors did not observe any cases of radiological ASD that manifested with clinical symptoms. Consequently, the incidence of ASD in this study is considerably lower than that reported by Qizhi et al. [20]. Nonetheless, this study has several limitations, including (a) a relatively small sample size of patients with degenerative cervical myelopathy (n=15), (b) a relatively short follow-up duration, (c) the inclusion of two different types of Zero-profile implants, which, although possessing similar mechanisms and structural designs, could potentially influence the functional outcomes, (d) the inclusion criteria were somewhat subjective, (e) radiological adjacent segment pathology and clinical adjacent segment pathology were not analyzed separately, and finally, (f) the study did not include a control group receiving either conservative treatment or cervical plating for comparison.

The overall outcomes of ACDF using Zero-Profile implants for single-level CSM have demonstrated satisfactory clinical and radiological results within a relatively short period. Although this study has certain limitations, we believe that, given the limited scientific literature on the use of these implants in the Indian context, multicentric trials involving a larger patient population and extended follow-up periods should be initiated.

Zero-profile implants (PEEK and titanium) provide safe, stable, and are equally effective for single-level ACDF in cervical spondylotic myelopathy with good fusion rates, minimal dysphagia, and significant functional recovery.

References

- 1. Cloward RB. The anterior approach for removal of ruptured cervical disks. J Neurosurg 1958;15:602-17. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 2. Korinth MC. Treatment of cervical degenerative disc disease – current status and trends. Zentralbl Neurochir 2008;69:113-24. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 3. Mummaneni PV, Kaiser MG, Matz PG, Anderson PA, Groff MW, Heary RF, et al. Cervical surgical techniques for the treatment of cervical spondylotic myelopathy. J Neurosurg Spine 2009;11:130-41. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 4. Kim SW, Limson MA, Kim SB, Arbatin JJ, Chang KY, Park MS, et al. Comparison of radiographic changes after ACDF versus Bryan disc arthroplasty in single and bi-level cases. Eur Spine J 2009;18:218-31. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 5. Pitzen TR, Chrobok J, Stulik J, Ruffing S, Drumm J, Sova L, et al. Implant complications, fusion, loss of lordosis, and outcome after anterior cervical plating with dynamic or rigid plates: Two-year results of a multi-centric, randomized, controlled study. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2009;34:641-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 6. Bazaz R, Lee MJ, Yoo JU. Incidence of dysphagia after anterior cervical spine surgery: A prospective study. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2002;27:2453-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 7. Kalb S, Reis MT, Cowperthwaite MC, Fox DJ, Lefevre R, Theodore N, et al. Dysphagia after anterior cervical spine surgery: Incidence and risk factors. World Neurosurg 2012;77:183-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 8. Park JB, Cho YS, Riew KD. Development of adjacent-level ossification in patients with an anterior cervical plate. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2005;87:558-63. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 9. Zhong ZM, Jiang JM, Qu DB, Wang J, Li XP, Lu KW, et al. Esophageal perforation related to anterior cervical spinal surgery. J Clin Neurosci 2013;20:1402-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 10. Mandal S, Bandyopadhyay U, MIzanur Rahman SK, Patel S, Roy R, Mandal S. Evaluation of outcome of zero-profile implant for anterior cervical discectomy and fusion in traumatic cervical sub-axial disc injury in Indian population: A prospective study. Int J Orthop Sci 2024;10:179-85. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 11. Son DK, Son DW, Kim HS, Sung SK, Lee SW, Song GS. Comparative study of clinical and radiological outcomes of a zero-profile device concerning reduced postoperative dysphagia after single level anterior cervical discectomy and fusion. J Korean Neurosurg Soc 2014;56:103-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 12. Chen YQ, Lu GH, Wang B, Li L, Kuang L. A comparison of anterior cervical discectomy and fusion (ACDF) using self-locking stand-alone polyetheretherketone (PEEK) cage with ACDF using cage and plate in the treatment of three-level cervical degenerative spondylopathy: A retrospective study with 2-year follow-up. Eur Spine J 2016;25:2255-62. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 13. Fraser JF, Härtl R. Anterior approaches to fusion of the cervical spine: A metaanalysis of fusion rates. J Neurosurg Spine 2007;6:298-303. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 14. Fujibayashi S, Neo M, Nakamura T. Stand-alone interbody cage versus anterior cervical plate for treatment of cervical disc herniation: Sequential changes in cage subsidence. J Clin Neurosci 2008;15:1017-22. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 15. Gercek E, Arlet V, Delisle J, Marchesi D. Subsidence of stand-alone cervical cages in anterior interbody fusion: Warning. Eur Spine J 2003;12:513-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 16. Sanden B, Olerud C, Petren-Mallmin M, Johansson C, Larsson S. The significance of radiolucent zones surrounding pedicle screws. Definition of screw loosening in spinal instrumentation. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2004;86:457-61. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 17. Song KJ, Choi BW, Jeon TS, Lee KB, Chang H. Adjacent segment degenerative disease: Is it due to disease progression or a fusion-associated phenomenon? Comparison between segments adjacent to the fused and non-fused segments. Eur Spine J 2011;20:1940-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 18. McAfee PC, Cunningham BW, Devine J, Williams E, Yu-Yahiro J. Classification of heterotopic ossification (HO) in artificial disk replacement. J Spinal Disord Tech 2003;16:384-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 19. Hirabayashi K, Miyakawa J, Satomi K, Maruyama T, Wakano K. Operative results and postoperative progression of ossification among patients with ossification of cervical posterior longitudinal ligament. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1981;6:354-64. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 20. Qizhi S, Peijia L, Lei S, Junsheng C, Jianmin L. Anterior cervical discectomy and fusion for noncontiguous cervical spondylotic myelopathy. Indian J Orthop 2016;50:390-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 21. Scholz M, Schnake KJ, Pingel A, Hoffmann R, Kandziora F. A new zero-profile implant for stand-alone anterior cervical interbody fusion. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2011;469:666-73. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 22. NohSH, Zhang HY. Comparison among perfect-C®, zero-P®, and plates with a cage in single-level cervical degenerative disc disease. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2018;19:33. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 23. Wang Z, Jiang W, Li X, Wang H, Shi J, Chen J, et al. The application of zero-profile anchored spacer in anterior cervical discectomy and fusion. Eur Spine J 2015;24:148-54. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 24. Lee MJ, Bazaz R, Furey CG, Yoo J. Influence of anterior cervical plate design on Dysphagia: A 2-year prospective longitudinal follow-up study. J Spinal Disord Tech 2005;18:406-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 25. Son DK, Son DW, Kim HS, Sung SK, Lee SW, Song GS. Comparative study of clinical and radiological outcomes of a zero-profile device concerning reduced postoperative dysphagia after single level anterior cervical discectomy and fusion. J Korean Neurosurg Soc 2014;56:103-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 26. Lu Y, Bao W, Wang Z, Zhou F, Zou J, Jiang W, et al. Comparison of the clinical effects of zero-profile anchored spacer (ROI-C) and conventional cage-plate construct for the treatment of noncontiguous bilevel of cervical degenerative disc disease (CDDD): A minimum 2-year follow-up. Medicine (Baltimore) 2018;97:e9808. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 27. Wang Z, Zhu R, Yang H, Shen M, Wang G, Chen K, et al. Zero-profile implant (Zero-p) versus plate cage benezech implant (PCB) in the treatment of single-level cervical spondylotic myelopathy. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2015;16:290. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 28. Matsumoto M, Okada E, Ichihara D, Watanabe K, Chiba K, Toyama Y, et al. Anterior cervical decompression and fusion accelerates adjacent segment degeneration: Comparison with asymptomatic volunteers in a ten year magnetic resonance imaging follow-up study. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2010;35:36-43. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 29. Lopez Espina CG, Amirouche F, Havalad V. Multilevel cervical fusion and its effect on disc degeneration and osteophyte formation. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2006;31:972-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 30. Gao Y, Liu M, Li T, Huang F, Tang T, Xiang Z. A meta analysis comparing the results of cervical disc arthroplasty with anterior cervical discectomy and fusion (ACDF) for the treatment of symptomatic cervical disc disease. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2013;95:555-61. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]