[box type=”bio”] What to Learn from this Article?[/box]

Diagnosis of Myositis ossificans progressiva at a young age can only be made if an alert clinician with subtle associated clinical findings looks for heterotropic calcification of soft tissue. Corticosteroids gives good pain relief for acute flare ups while bisphosphonates can be given for long term.

Case Report | Volume 5 | Issue 4 | JOCR Oct-Dec 2015 | Page 10-13 | Ganesan G Ram, Karthik Anand .K, P.V.Vijayaraghavan. DOI: 10.13107/jocr.2250-0685.333 .

Authors: Ganesan G Ram[1], Karthik Anand .K[1], P.V.Vijayaraghavan[1].

[1] Department Of Orthopaedics, Sri Ramachandra Medical College, Porur, Chennai – 600116. India.

Address of Correspondence

Dr. Ganesan G Ram,

Department of Orthopaedics, Sri Ramachandra Medical College, Porur. Chennai – 600116. India.

E mail: Ganesangram@Yahoo.Com

Abstract

Introduction: Myositis ossificans progressiva is very rare with a worldwide prevalence of approximately 1 case in 2 million individuals. No ethnic, racial, or geographic predisposition has been described. Although familial forms inherited on a dominant autosomal basis have been described, most cases are sporadic.

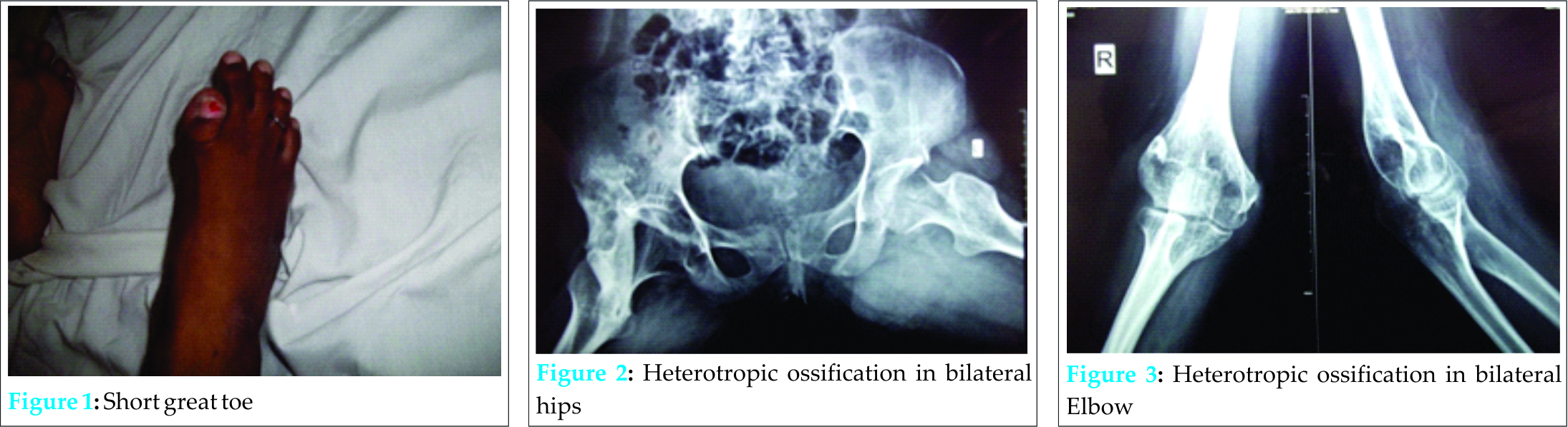

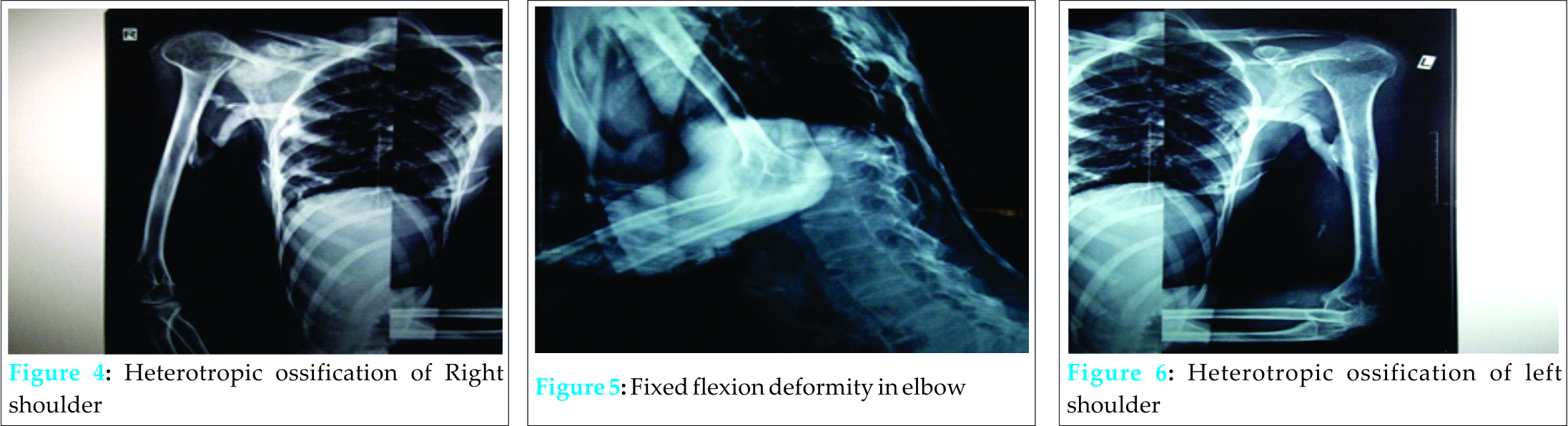

Case Report: 16 yr female came to opd with complaints of progressive restriction of movements of bilateral elbow, bilateral shoulder, bilateral knee and bilateral hip for past 4 years. On examination patient is found to have short great toes of bilateral foot and ffd of all the joints. Patient is bed ridden and had acute pain for past 2 wks. Patient was evaluated and diagnosed to have myositis ossificans progressiva. Patient was treated with short course of steroids and bisphosphonates. Patient’s pain improved and the patient was discharged on request as she was not willing for further management.

Conclusion: Myositis ossificans progressiva is a rare disease with limited treatment options. At present there is no available treatment to completely cure the disease. Short course of steroids and bisphosphonates helps to relieve symptoms of acute pain.

Keywords: Myositis ossificans progressive, Fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva, Bisphosphonates.

Introduction

Myositis ossificans progressiva [1] is a severely disabling heritable disorder of connective tissue characterized by congenital malformations of the great toes(hallux valgus, malformed first metatarsal, and/or monophalangism) and progressive heterotopic ossification (HO) that forms qualitatively normal bone in characteristic extraskeletal sites. This condition manifests in childhood and runs a slowly progressive course. “Stone man disease” and “myositis ossificans progressiva” were the names used initially, but “FOP” more accurately reflects the pathogenesis of the disease. Involvement of dorsal, axial, cranial, and proximal anatomic locations precede involvement of ventral, appendicular, caudal, and distal areas of the body [2].

Case report

16 yr female came to out patient department with complaints of progressiva restriction of movements of bilateral elbow, bilateral shoulder, bilateral knee and bilateral hip for past 4 years. On examination patient was found to have short great toes of bilateral foot and ffd of all the joints. Patient was the only child to non consanguineous parents and none of the family members had same problem. Developmental history was normal. Patient is bed ridden and had acute pain for past 2 wks. Patient was evaluated and diagnosed to have fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva. Patient was treated with short course of steroids and bisphosphonates. Patient’s pain improved and the patient was discharged on request as she was not willing for further management.

Discussion

Epidemiology

FOP is very rare with a worldwide prevalence of approximately 1 case in 2 million individuals. No ethnic, racial, or geographic predisposition has been described [3]. Although familial forms inherited on a dominant autosomal basis have been described,most cases are sporadic.

Clinical Description

FOP is the most disabling condition of ectopic skeletogenesis. Children who have FOP appear normal at birth except for congenital malformations of the great toes .Typically, during the first decade of life, sporadic episodes of painful soft tissue swellings (flare-ups) occur and are commonly mistaken for tumors[4]. Although some exacerbations spontaneously regress, flare-ups can transform skeletal muscles, tendons, ligaments, fascia, and aponeuroses through an endochondral process into ribbons, sheets, and plates of heterotopic bone that span the joints, lock them in place, and render movement impossible[5,6] .Progressive episodes of HO occur in specific anatomic patterns, and are typically seen first in the dorsal, axial, cranial, and proximal regions of the body and later in the ventral, appendicular, caudal, and distal regions[7]. Attempts to remove this heterotopic bone usually lead to episodes of explosive new bone formation.

Trauma such as minor soft tissue injury, muscular stretching, over-exertion and fatigue, intramuscular immunizations, injections for dental work, falls, and influenza-like illnesses can induce flare-ups of the condition. Immobility is cumulative and most patients are wheelchair-bound by the end of the second decade of life. The diaphragm, tongue, and extra-ocular muscles are spared from HO. Cardiac muscle and smooth muscle is also spared in FOP. Neck stiffness is an early finding and can precede the appearance of HO at that site. Cervical spine abnormalities include large posterior elements, tall narrow vertebral bodies, and fusion of the facet joints between C2 and C7 [8]. The cervical spine often becomes ankylosed early in life. Other skeletal features associated with FOP are short malformed thumbs, clinodactyly, short broad femoral necks, and proximal medial tibial osteochondromas[9,10,11]. In addition to progressive immobility, other life-threatening complications include severe weight loss following ankylosis of the jaw, as well as pneumonia and right-sided heart failure resulting from thoracic insufficiency syndrome (TIS)[12]. Features of FOP that contribute to TIS include costovertebral malformations with orthotopic ankylosis of the costovertebral joints, ossification of intercostal muscles, paravertebral muscles and including kyphoscoliosis or thoracic lordosis. Limb swelling seen with flare-ups may be substantial and lead to extra-vascular compression of nerves and tissue lymphatics.

Some patients with advanced FOP involving the lower limbs have venous stasis and/or lymphedema. Hearing loss is usually conductive and may be due to middle ear ossification, but in some patients the hearing impairment is sensorineural, involving the inner ear, cochlea, or the auditory nerve[13].

Diagnosis and diagnostic methods

Clinical suspicion of FOP early in life on the basis of malformed great toes can lead to early clinical diagnosis and the avoidance of harmful diagnostic and treatment procedures. Routine biochemical evaluations do not contribute to making the diagnosis. Plain X-rays can substantiate more subtle great toe abnormalities and the presence of HO. Abnormal findings on bone scan occur before HO can be detected by conventional radiography, but sophisticated imaging studies are generally superfluous from a diagnostic standpoint. Confirmatory genetic testing is available on a clinical and research basis at several laboratories[14].

Differential Diagnosis

FOP is commonly misdiagnosed as aggressive juvenile fibromatosis, lymphedema, or soft tissue sarcoma. Other diagnostic considerations are lymphoma, desmoids tumors, isolated congenital malformations, brachydactyly

(isolated), and juvenile bunions

Preventative measures

In children, restriction of activity to less physically interactive play may be helpful to reduce falls. Physical rehabilitation should be focused on enhancing activities of daily living through approaches that avoid passive range of motion which could lead to disease flare-ups. Acceptable modification of activity, improvement in household safety, ambulatory devices, and use of protective headgear are all strategies to prevent falls and minimize injury when falls occur. Prophylactic measures that minimize respiratory decline (e.g., incentive spirometry) and prevent influenza and pneumonia (i.e.,appropriate immunizations) may decrease morbidity and mortality associated with thoracic insufficiency syndrome. Intramuscular injections, including immunizations, must be avoided, but vaccinations administered by subcutaneous injection and routine venipuncture pose little risk. Great care is necessary in administering dental care, particularly in avoiding overstretching of the jaw and intramuscular injections of local anesthetic .Preventive oral and dental health care measures are essential. Successful anesthesia in mandibular primary teeth can be achieved by infiltration through the dentalpulp. Interligamentary infiltration may be helpful, if performed carefully. General anesthesia with awake nasotracheal Fiber optic intubation may be needed for dental care in some patients. Conductive hearing loss is common and children should generally have audiology evaluations at least every other year. Surgical attempts to remove heterotopic bone will provoke explosive new bone growth and should not be attempted.

Pharmacotherapy

Corticosteroids are indicated as first-line treatment at beginning of flare-ups. A brief 4 day course of high-dose corticosteroids, started within the first 24 hours of a flare-up, may help reduce the intense inflammation and tissue edema seen in the early stages of the disease. The use of corticosteroids should be restricted to treatment of flare-ups that affect major joints, the jaw, or the submandibular area. When prednisone is discontinued, a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) or cox-2 inhibitor (in conjunction with a leukotriene inhibitor) may be used symptomatically for the duration of the flare-up. The use of mast cell inhibitors and amino bisphosphonates can be used at the physician’s discretion. Many flare-ups are extremely painful and may require a brief course of well-monitored narcotic analgesia in addition to the use of NSAIDs, cox-2 inhibitors, and oral or intravenous glucocorticoids. The cautious short term use of muscle relaxants such as cyclobenzaprine (Flexeril), metaxalone (Skelaxin), or Lioresal (Baclofen) may help to decrease muscle spasm and maintain more functional activity.

Prognosis

The median lifespan is approximately 40 years of age. Most patients are wheelchair-bound by the end of the second decade of life and commonly die of complications of thoracic insufficiency syndrome[15].

Conclusion

Myositis ossificans progressiva is a rare disease with limited treatment options. Presently- there are no treatment options to completely cure it. Short course of steroid and bisphosphonate can relieve patients with acute pain.

Clinical Message

Despite the growth in knowledge of metabolic bone diseases, little progress has been made in understanding the pathophysiology of myositis ossificans progressiva. The progressive, disabling nature of myositis ossificans progressiva underscores the importance of studies that treat patients with early disease. The most promising approaches currently under investigations are angiogenesis inhibition(thalidomide),mast cell inhibition(montelukast), and BMP4 inhibition(experimental treatments).

References

1. OMIM: Mendelian Inheritance in Man.[http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/omim].

2. Pignolo RJ, Shore EM, Kaplan FS. Fibrodysplasia OssificansProgressiva: Clinical andGenetic Aspects. Pignoloet al. Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases 2011, 6:80.http://www.ojrd.com/content/6/1/80.

3. Shore EM, Feldman GJ, Xu M, Kaplan FS: The genetics of fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva. Clin Rev Bone Miner Metab 2005,3:201-204.

4 .Kitterman JA, Kantanie S, Rocke DM, Kaplan FS: Iatrogenic harm caused by diagnostic errors in fibrodysplasiaossificansprogressiva. Pediatrics 2005;116:e654-e661.

5. Cohen RB, Hahn GV, Tabas JA, Peeper J, Levitz CL, Sando A, et al. The natural history of heterotopic ossification inpatients who have fibrodysplasiaossificansprogressiva. A study of fortyfourpatients. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1993;75:215-219.

6. Kaplan FS, Glaser DL, Shore EM, Deirmengian GK, Gupta R, Delai Pet al. The phenotype of fibro dysplasia ossificans progressiva. Clin Rev Bone MinerMetab 2005;3:183-188.

7. Pignolo RJ, Suda RK, Kaplan FS. The fibrodysplasiaossificans progressive lesion. Clin Rev Bone Miner Metabol 2005;3:195-200.

8. Schaffer AA, Kaplan FS, Tracy MR, O’Brien ML, Dormans JP, Shore EM et al.Developmental anomalies of the cervical spine in patients with fibrodysplasiaossificansprogressiva are distinctly differentfrom those in patients with Klippel-Feil syndrome. Spine 2005;30:1379-1385.

9. Kaplan FS, Strear CM, Zasloff MA. Radiographic and scintigraphic features of modeling and remodeling in the heterotopic skeleton of patients who have fibrodysplasiaossificansprogressiva. ClinOrthopRelat Res 1994;238-47.

10. Deirmengian GK, Hebela NM, O’Connell M, Glaser DL, Shore EM, Kaplan FS. Proximaltibialosteochondromas in patients with fibrodysplasiaossificansprogressiva. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2008;90:366-374.

11. Kaplan FS, Xu M, Seemann P, Connor M, Glaser DL, Carroll L et al. Classic andatypical fibrodysplasiaossificansprogressiva (FOP) phenotypes are caused by mutations in the bonemorphogenetic protein (BMP) type I receptor ACVR1. Hum Mutat 2009;30:379-90.

12. Kaplan FS, Glaser DL. Thoracic insufficiency syndrome in patients with fibrodysplasiaossificansprogressiva. Clin Rev Bone Miner Metab 2005;3:213-216.

13. Levy CE, Lash AT, Janoff HB, Kaplan FS. Conductive hearing loss in individuals with fibrodysplasiaossificansprogressiva. Am J Audiol1999;8:29-33.

14.Kaplan FS, Xu M, Glaser DL, Collins F, Connor M, Kitterman J et al. Early diagnosis of fibrodysplasiaossificansprogressiva. Pediatrics 2008;121:e1295-e1300.

15.Kaplan FS, Zasloff MA, Kitterman JA, Shore EM, Hong CC, Rocke DM. Early mortality and cardiorespiratory failure in patients with fibrodysplasiaossificansprogressiva. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2010;92:686-691.doi:10.1186/1750-1172-6-80.Cite this article as: Pignoloet al.: FibrodysplasiaOssificansProgressiva:Clinical and Genetic Aspects. Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases 2011 6:80.

| How to Cite This Article: Ram GG, Karthik AK, Vijayaraghavan PV. The stone women-Myositis ossificans Progressiva . Journal of Orthopaedic Case Reports 2015 Oct-Dec;5(4): 10-13. Available from: https://www.jocr.co.in/wp/2015/10/01/2250-0685-333-fulltext/ |

[Full Text HTML] [Full Text PDF] [XML]

[rate_this_page]

Dear Reader, We are very excited about New Features in JOCR. Please do let us know what you think by Clicking on the Sliding “Feedback Form” button on the <<< left of the page or sending a mail to us at editor.jocr@gmail.com