[box type=”bio”] Learning Points for this Article: [/box]

Minimally invasive cerclage wiring is an excellent alternative to interfragmentary screw fixation as an adjunct to osteosynthesis in femoral fractures.

Case Report | Volume 7 | Issue 4 | JOCR July – August 2017 | Page 39-43| Sanjay Agarwala, Aditya Menon, Sameer Chaudhari. DOI: 10.13107/jocr.2250-0685.842

Authors: Sanjay Agarwala[1], Aditya Menon[1], Sameer Chaudhari[1]

[1] Department of Orthopedics and Traumatology, P D Hinduja Hospital and Medical Research Centre, Mahim, Mumbai, Maharashtra, India.

Address of Correspondence:

Dr. Sanjay Agarwala, Department of Orthopedics and Traumatology, P D Hinduja Hospital and Medical Research Centre, Veer Savarkar Marg, Mahim (West), Mumbai – 400 016, Maharashtra, India.

E-mail: drsa2011@gmail.com

Abstract

Introduction: Cerclage wiring has been used in the past for osteosynthesis of femoral fractures. However, the technique went into disrepute as extensive soft tissue dissection, and periosteal stripping increased the risk of bone necrosis and delayed union. Advent of new instrumentation and minimally invasive technique has significantly reduced these complications. In spite of the limited indications for its application, reduction and stabilization with cerclage wiring can supplement osteosynthesis especially in spiral or oblique fracture morphology or those with a butterfly fragment instead of interfragmentary screw fixation. This series attempts to describe the feasibility and evaluate outcomes of cerclage wiring as an adjunct to osteosynthesis and reestablish its place in reduction and fixation of femur fractures.

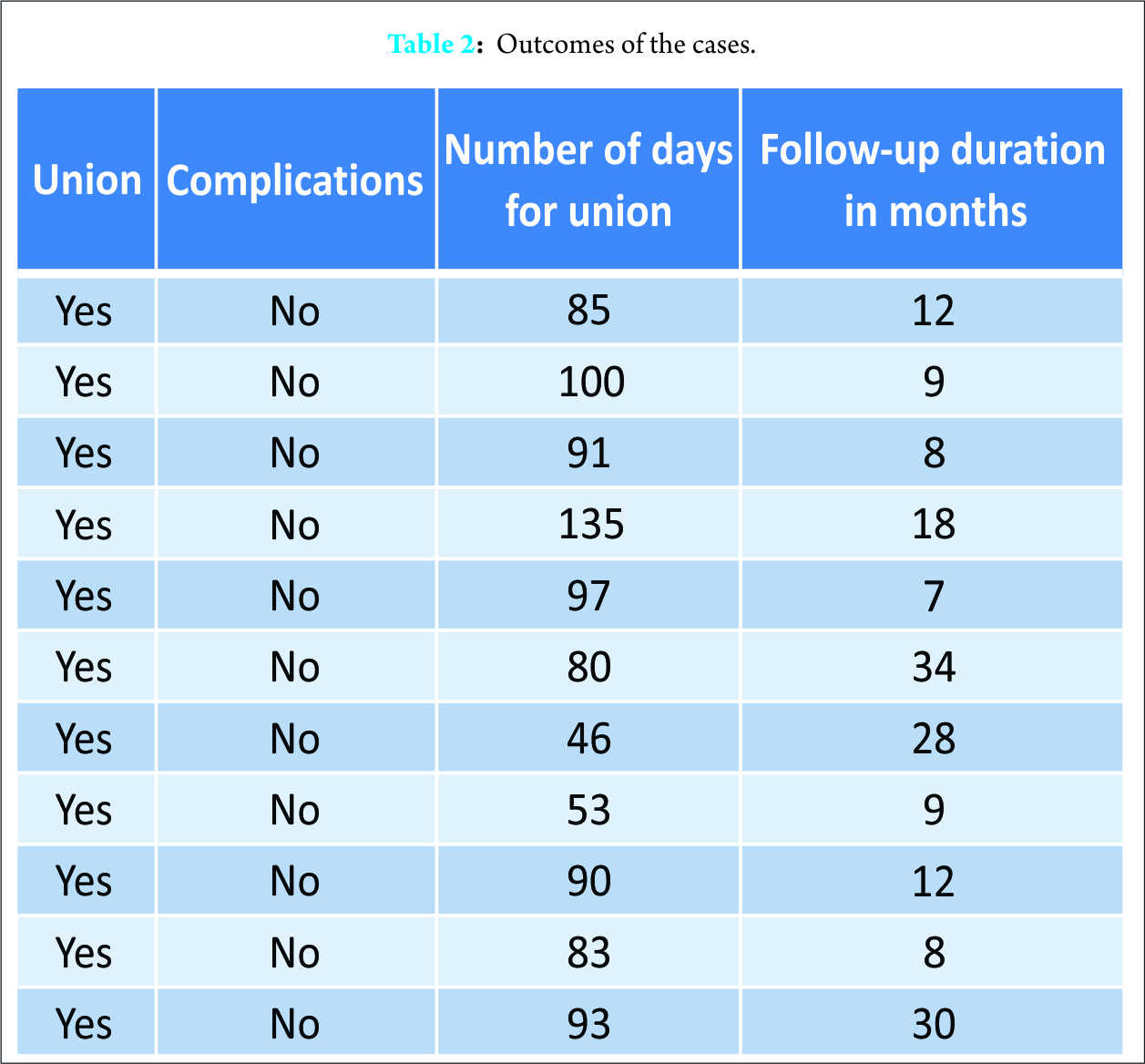

Case Report: This is a retrospective case series of patients (January 2011 to October 2015) in whom cerclage wiring was used as an adjunct to osteosynthesis of primary and periprosthetic fractures of femur. Patient demographics, number of wires used, implant used for osteosynthesis, number of days to union, union rate and complications were recorded and analyzed. The patients were followed up for a minimum of 6 months. 11 patients (7 female and 4 male) with a mean age of 67.10 ± 21.64 years were studied. The number of patients with intertrochanteric, subtrochanteric, diaphyseal, and periprosthetic fractures of the femur was two, five, one, and three, respectively. Internal fixation was done with plates in six and cephalomedullary nails in five patients. Mean total number of wires used was 2.10 ± 0.70. Mean duration of follow-up was 15.91 ± 10.03 months. Union was achieved in all cases with a mean duration of 86.63 ± 22.44 days. There were no complications in our study.

Conclusion: Cerclage wiring technique helps to achieve stable reduction of femoral fractures which can then be supplemented with a nail or a plate. The minimally invasive technique and instrumentation offer the advantage of minimal soft tissue dissection, and the procedure is associated with excellent outcomes without any major complications.

Keywords: Cerclage wiring, femur fracture, percutaneous cerclage wiring, periprosthetic fracture.

Introduction

Cerclage wiring is useful as an adjunct to osteosynthesis of femoral fractures especially spiral, oblique; those with a butterfly fragment and in periprosthetic fractures instead of interfragmentary screws [1, 2]. The objective of cerclage wiring is to optimize fracture fixation which is achieved due to its biomechanical properties, ease of use, reliability of fixation, and stability offered [1]. Traditionally performed cerclage procedure using an open technique resulted in significant soft tissue and periosteal stripping [2]. It also caused strangulation of blood vessels resulting in compromised blood supply to that segment of bone which hampered fracture healing [2]. Moreover, cerclage wiring alone does not provide adequate stability to the fracture, and it needs to be supplemented with a nail or plate. Cerclage wiring technique went into disrepute due to these limitations and poor results and was discarded as a technique to supplement fracture reduction and fixation [3]. However, today; there is renewed interest in cerclage wiring technique, more so in periprosthetic fractures [4]. Minimally invasive cerclage wiring has also been used in combination with plates or intramedullary nails in subtrochanteric fracture or femoral shaft fracture [1, 5, 6]. There is limited published data on the use of cerclage wiring technique in Indian patients [7, 8]. This paper attempts to reestablish the place of correctly utilized cerclage technique to complement fracture reduction and fixation in difficult fractures. The objective of this study was to evaluate the feasibility and outcomes of cerclage wiring with osteosynthesis for the treatment of fractures of the femur.

Case Report

This is a retrospective case series of patients with femoral fractures (intertrochanteric, subtrochanteric, diaphyseal, and periprosthetic) treated with cerclage wiring and osteosynthesis with a plate or nail at a tertiary care center (PD Hinduja Hospital and Research Center, Mahim) in Mumbai from January 2011 to October 2015. Surgery was done within 24 h following injury in all cases. All patients were given appropriate splintage preoperatively. Postoperatively, patients were treated with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medicines, calcium and oral Vitamin D supplements. Radiographs were taken immediately after surgery and every 4 weeks thereafter till fracture union. Bone grafting was not done in any case. Patients with open fractures, aseptic or infected non-union at presentation to us and those with follow-up of <6 months were excluded from the study. The number of wires used, implant used for osteosynthesis, outcome (union or complication), follow-up duration, and time required for fracture union were recorded. Union was defined as the ability to walk full weight bearing without pain and radiographs showing signs of bony union.

A total of 11 patients (male: 4 [36.4%]; female: 7 [63.6%]) underwent minimally invasive cerclage wiring during the study period. The overall mean age of patients was 67.10 ± 21.64 years while the mean age of males and females was 48.25 ± 26.68 and 80.71 ± 11.34 years, respectively.

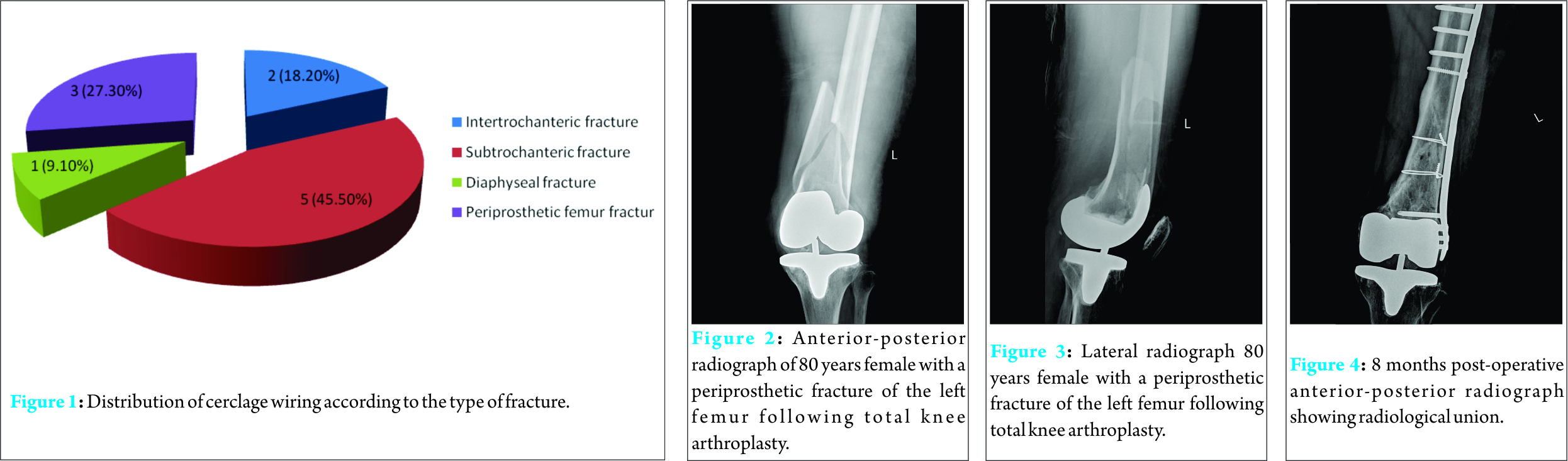

The numbers and percentages of patients with a type of fracture are shown in Fig. 1. The details of each case are given in Table 1. The mean total number of wires used was 2.10 ± 0.70.

The mean follow-up duration of all cases was 15.91 ± 10.03 months. The union rate was 100% without any complication (Table 2). The mean duration required for union of fractures was 86.63 ± 22.44 day with a range from 46 to 135 days.

Discussion

The technique of cerclage wiring has been used by orthopedic surgeons for many years [4]; however, it went into disrepute because of some limitations associated with the procedure. Conventional open reduction with extensive soft tissue dissection and periosteal stripping increases the risk of infection, bone necrosis and delayed union [2]. It was postulated that the blood supply to the fractured bone, a necessary prerequisite for bone healing may be compromised due to cerclage usage [2]. The other possible limitations and complications associated with the use of cerclage wiring include insufficient reduction of the fracture, and migration of the broken wire [4]. Moreover, standalone cerclage wiring may be too weak to perform the function of fixation [3, 9]. However, the interest in cerclage wiring technique has been revived in the recent past due to minimal invasive reduction, better understanding of biomechanics [4] and increasing number of periprosthetic fractures [3, 9].

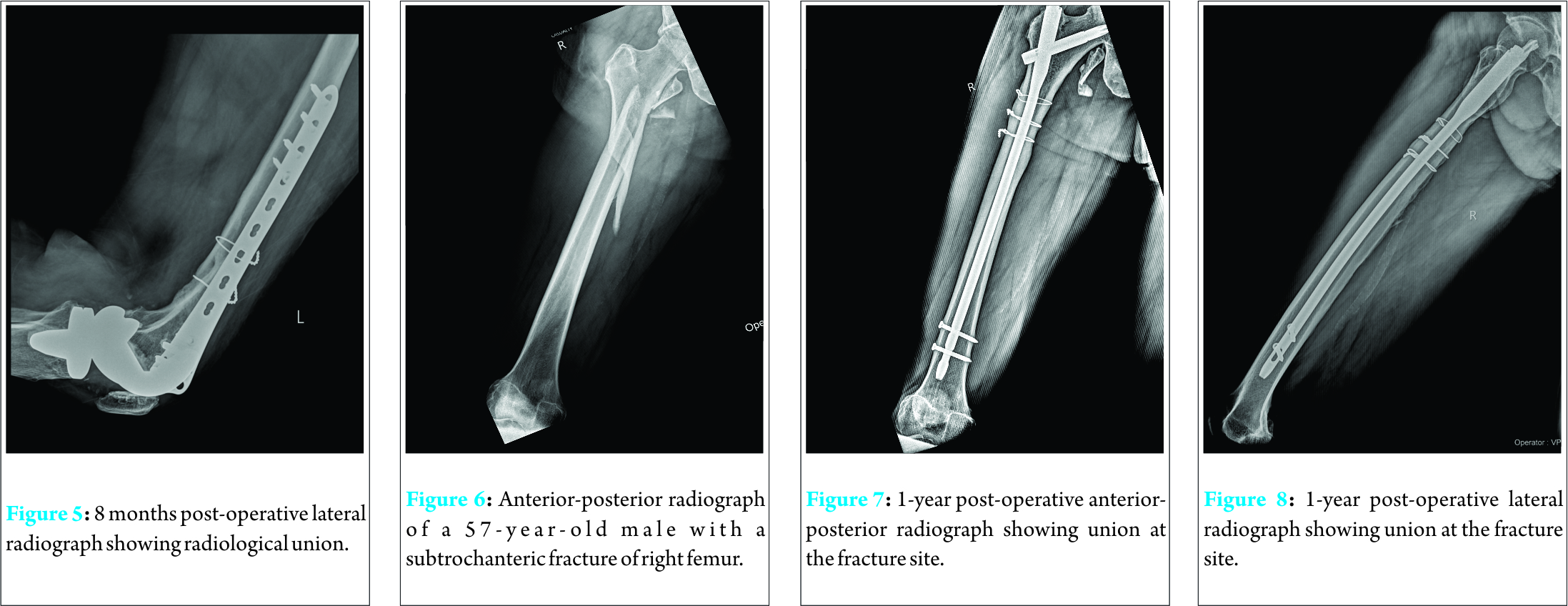

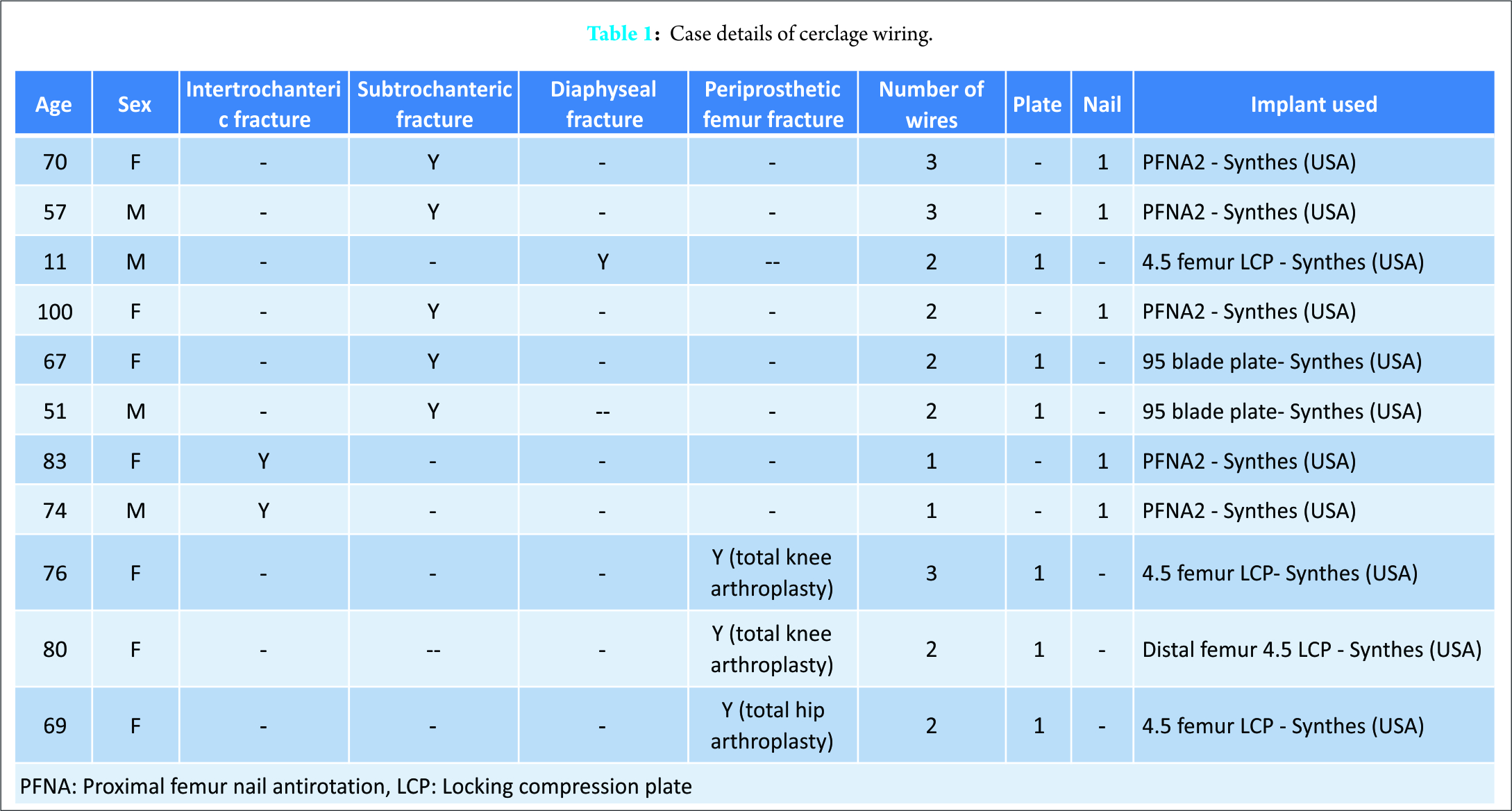

Minimally invasive cerclage technique and instrumentation do not damage the blood supply as there is minimal soft tissue dissection. Moreover, the blood vessels reach the bone primarily in a centripetal direction resulting in minimal disruption by cerclage wiring around the bone [3]. Cerclage wiring provides additional stability to the reduced fracture through centripetal force [3]. Management of periprosthetic femoral fractures can be quite challenging [10]. Cerclage wires are especially useful in stabilizing the proximal femoral fracture after stem insertion in total hip arthroplasty [11]. Cerclage wiring is particularly useful where surgeon faces difficulty for screw placement in periprosthetic fractures, and they provide satisfactory outcomes when used for fixation of periprosthetic femoral fractures. Blocking of the intramedullary canal by prosthesis makes it difficult to use a screw with bicortical purchase [12]. The wires do not interfere with fixation or obstruct the intramedullary canal [3, 11, 13]. In our case series, three patients had periprosthetic fractures. All cases of periprosthetic fracture were treated with cerclage wiring and plating and resulted in excellent outcome with the union without any complication or need for revision surgery (Fig. 2, 3, 4, 5).

The limitation of extensive surgical handling for passing the wires can be minimized or avoided by using principles of minimally invasive procedure which may improve the clinical utility of cerclage wiring [10]. In this regard, the cerclage passing instrument can be of great help for direct fracture reduction. The newer instruments can allow passage of the wire through a small incision (2-3 cm) resulting in less disruption of blood supply compared to an open wiring method. A cadaveric study has shown that percutaneous cerclage wiring results in minimal disruption of the femoral blood supply [2]. Subtrochanteric femur fractures also pose a challenge for management due to their anatomical and biomechanical features [14]. Fracture malalignment and nonunion are common concerns after the treatment of subtrochanteric fractures with intramedullary nailing [5]. Cerclage wiring is an option for the treatment of such cases. It can assist and maintain a reduction in subtrochanteric fractures and complement intramedullary or extramedullary fixation resulting in a better outcome [5]. In our series, subtrochanteric fractures were the most common indication for the use of cerclage wiring. Cerclage wires helped achieve stable near anatomical reduction which was then augmented with a cephalomedullary nail or plate. We used a combination of cephalomedullary nail and cerclage wiring in three out of five cases while in the other two, it was used in conjunction with 95° blade plate. Union was seen in all cases without any complications (Fig. 6, 7, 8). Titanium locking plates and stainless steel cerclage wires have been successfully used in minimally invasive closed reduction and internal fixation of femoral fractures without any adverse impact on fracture healing [1]. Our results are in accordance with these findings. Stainless steel cerclage wires are preferred in the clinical practice due to their biomechanical characteristics, ease of use and reliability for internal fixation with good stability [14, 16, 17]. Minimal invasive technique used to pass wires achieves rotational, sagittal and coronal alignment after which the fracture is spanned with either a plate which may be passed submuscularly or an intramedullary nail. A study by Han et al. evaluated the number of wires required for the management of proximal femur fracture in cementless total hip arthroplasty. In this study, three wires were needed to achieve stability [18]. In a comparative experimental study, Lenz et al. [9] have shown that double looped wires perform significantly better in terms of providing fixation stability compared with single looped wires. Thus, multiple wires provide better strength for reduction and maintenance of fracture compared to a single wire. A study has shown that cerclage wire or cable provides excellent mid- to long-term results in the management of intraoperative fracture associated with cementless, tapered femoral prosthesis [14]. Average number of wires used in our study was 2.10 ± 0.70. In our series, intertrochanteric fractures were fixed with a single wire each, while two wires were used in the diaphyseal fracture (Fig. 9, 10, 11). Of the five subtrochanteric fractures, three were fixed with two wires while the other two cases were stabilized with three wires each. Two of the periprosthetic fractures were fixed with two wires each while the third case had three cerclage wires. Our results suggest that the use of cerclage wiring in combination with standard fixation techniques helps achieve primary near anatomical stable alignment and therefore facilitates fracture healing with no significant complications. Minimally invasive procedure and instrumentation preserve soft tissue attachments thus preserving the vascular supply to the involved bone segment [2, 3]. The results of our study are significant in light of the limited literature on the use of cerclage wiring in femoral fractures in Indian patients [7, 8]. We believe that cerclage wiring can be used as a substitute for interfragmentary screw fixation which requires extensive soft tissue dissection. This should, however, be confirmed with a double-blinded, randomized comparative study. Our study has some limitations. First, this is a retrospective study with limited sample size. Second, there was no control arm to compare the outcomes of the procedure with other techniques. Larger comparative studies are required to confirm the observations from our case series.

Conclusion

Our retrospective case series of 11 patients strongly supports the use of cerclage wiring technique to achieve stable near anatomical reduction as an adjunct to osteosynthesis of femoral fractures. Thus, it supplements the intramedullary nail or plate and enhances fracture healing. Minimally invasive technique and instrumentation causes minimal soft tissue dissection and preserves vascularity. This technique is associated with minimal or no complications with the excellent outcome if performed carefully.

Clinical Message

This paper highlights the advantages of minimally invasive instrumentation and technique, thus avoiding the complications associated with the older method of cerclage wiring which involved extensive soft tissue and periosteal stripping. It is an alternative to interfragmentary screw fixation which involves extensive soft tissue dissection. Cerclage wiring can thus be used as an adjunct to definitive fixation in femur fractures.

References

1. El-Zayat BF, Ruchholtz S, Efe T, Paletta J, Kreslo D, Zettl R. Results of titanium locking plate and stainless steel cerclage wire combination in femoral fractures. Indian J Orthop 2013;47(5):454-458.1. El-Zayat BF, Ruchholtz S, Efe T, Paletta J, Kreslo D, Zettl R. Results of titanium locking plate and stainless steel cerclage wire combination in femoral fractures. Indian J Orthop 2013;47(5):454-458.

2. Apivatthakakul T, Phaliphot J, Leuvitoonvechkit S. Percutaneous cerclage wiring, does it disrupt femoral blood supply? A cadaveric injection study. Injury 2013;44(2):168-174.

3. Perren SM, Fernandez Dell’Oca A, Lenz M, Windolf M. Cerclage, evolution and potential of a Cinderella technology. An overview with reference to periprosthetic fractures. Acta Chir Orthop Traumatol Cech 2011;78(3):190-199.

4. Angelini A, Battiato C. Past and present of the use of cerclage wires in orthopedics. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol 2015;25(4):623-635.

5. Tomas J, Teixidor J, Batalla L, Pacha D, Cortina J. Subtrochanteric fractures: Treatment with cerclage wire and long intramedullary nail. J Orthop Trauma 2013;27:2157-2160.

6. Tscherne H, Haas N, Krettek C. Intramedullary nailing combined with cerclage wiring in the treatment of fractures of the femoral shaft. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1986;212:62-67.

7. Marya SK, Thukral R. Extensively coated revision stems in proximally deficient femur: Early results in 15 patients. Indian J Orthop 2008;42(3):287-293.

8. Das R, Srivastava P, Singh A, Sharma H. Management of difficult fractures of proximal third of femur with K nail in a secondary healthcare facility. Int J Sci Stud 2015;3:90-93.

9. Lenz M, Perren SM, Richards RG, Mückley T, Hofmann GO, Gueorguiev B, et al. Biomechanical performance of different cable and wire cerclage configurations. Int Orthop 2013;37(1):125-130.

10. Apivatthakakul T, Phornphutkul C, Bunmaprasert T, Sananpanich K, Fernandez Dell’Oca A. Percutaneous cerclage wiring and minimally invasive plate osteosynthesis (MIPO): A percutaneous reduction technique in the treatment of Vancouver Type B1 periprosthetic femoral shaft fractures. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2012;132(6):813-822.

11. Fishkin Z, Han SM, Ziv I. Cerclage wiring technique after proximal femoral fracture in total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 1999;14(1):98-101.

12. Wähnert D, Lenz M, Schlegel U, Perren S, Windolf M. Cerclage handling for improved fracture treatment. A biomechanical study on the twisting procedure. Acta Chir Orthop Traumatol Cech 2011;78(3):208-214.

13. Berend KR, Lombardi AV Jr, Mallory TH, Chonko DJ, Dodds KL, Adams JB. Cerclage wires or cables for the management of intraoperative fracture associated with a cementless, tapered femoral prosthesis: Results at 2 to 16 years. J Arthroplasty 2004;19 7 Suppl 2:17-21.

14. Hoskins W, Bingham R, Joseph S, Liew D, Love D, Bucknill A, et al. Subtrochanteric fracture: The effect of cerclage wire on fracture reduction and outcome. Injury 2015;46(10):1992-1995.

15. Carls J, Kohn D, Rössig S. A comparative study of two cerclage systems. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 1999;119(1-2):67-72.

16. Bostrom MP, Asnis SE, Ernberg JJ, Wright TM, Giddings VL, Berberian WS, et al. Fatigue testing of cerclage stainless steel wire fixation. J Orthop Trauma 1994;8(5):422-428.

17. Shaw JA, Daubert HB. Compression capability of cerclage fixation systems. A biomechanical study. Orthopedics 1988;11(8):1169-1174.

18. Han SM. Comparison of wiring techniques for bone fracture fixation in total hip arthroplasty. Tohoku J Exp Med 2000;192(1):41-48.

|

|

|

| Dr. Sanjay Agarwala | Dr. Aditya Menon | Dr. Sameer Chaudhari |

| How to Cite This Article: Agarwala S, Menon A, Chaudhari S. Cerclage Wiring as an Adjunct for the Treatment of Femur Fractures: Series of 11 Cases. Journal of Orthopaedic Case Reports 2017 Jul-Aug;7(4):39-43. |

[Full Text HTML] [Full Text PDF] [XML]

[rate_this_page]

Dear Reader, We are very excited about New Features in JOCR. Please do let us know what you think by Clicking on the Sliding “Feedback Form” button on the <<< left of the page or sending a mail to us at editor.jocr@gmail.com