[box type=”bio”] Learning Points for this Article: [/box]

Although the giant-cell tumor is pathology of fused epiphysis, it can be a conceded as clinical differential diagnosis even in skeletal immature patient.

Case Report | Volume 7 | Issue 5 | JOCR September – October 2017 | Page 20-23| Pankaj Kumar Mishra, Yash Agrawal, Prakhar Singhal, Kripa Shankar Mishra. DOI: 10.13107/jocr.2250-0685.880

Authors: Pankaj Kumar Mishra [1], Yash Agrawal [1], Prakhar Singhal [1], Kripa Shankar Mishra [1]

[1] Department of Orthopaedics, Gandhi Medical College, Bhopal, Madhya Pradesh, India.

Address of correspondence

Dr. Pankaj Kumar Mishra,

Department of Orthopaedics, Gandhi Medical College, Bhopal, Madhya Pradesh, India.

E-mail: drpankajv@yahoo.com

Abstract

Introduction: In the customary wisdom, it is conceded that giant-cell tumor (GCT) is a pathology of fused epiphysis, but there are literatures available to depict that even though rare bit, but it occurs in the skeletally immature patients. Here, we are presenting a rare case of GCT of the fifth metacarpal in the skeletally immature patient.

Case Report: It is a case report of a 13-year-old girl with the history of swelling over her right hand for 5 months. X-ray revealed that there was an osteolytic fusiform expansible lesion. The biopsy sent and it conferred the diagnosis of GCT. Dorsal approach used for the enbloc resection of the fifth metacarpals (except at the base) and partial excision of the surrounding muscles done. The capsule and collateral ligament of the fifth metacarpophalangeal joint were left. The fourth metatarsal was harvested from the foot along with its capsule and collateral ligament of the metatarsophalangeal joint and sutured to the counter capsuloligamentous structure at the recipient site.

Conclusion: In our case, we are presenting the GCT of metacarpal in a skeletally immature patient, which was managed by osteoarticular graft. Management by autologous metatarsal graft is a nontraditional approach. We bring it to the horizon of knowledge to discuss the clinical and radiological presentation with surgical as well as functional outcome.

Keywords: Giant-cell tumor, skeletally immature, metacarpal, osteoarticular, metatarsal.

Introduction

Usually, it is conceded that giant-cell tumor (GCT) is pathology of fused epiphysis, but there are literatures available to depict that even though rare, but it occurs in the skeletally immature patients [1, 2]. Puri et al. studied the GCT among Indian population of open physis, and they found that overall incidence of GCT is higher in the Asian population but had the marked (82%) female preponderance [3]. There are very few available literatures, discussing about the GCT of metacarpal in skeletally immature population [4]. Here, we are presenting a rare case of GCT of the fifth metacarpal in the skeletally immature patient. In this case report, the GCT was removed along with metacarpophalangeal joint and followed by reconstruction of joint by the ipsilateral metatarsal.

Case Report

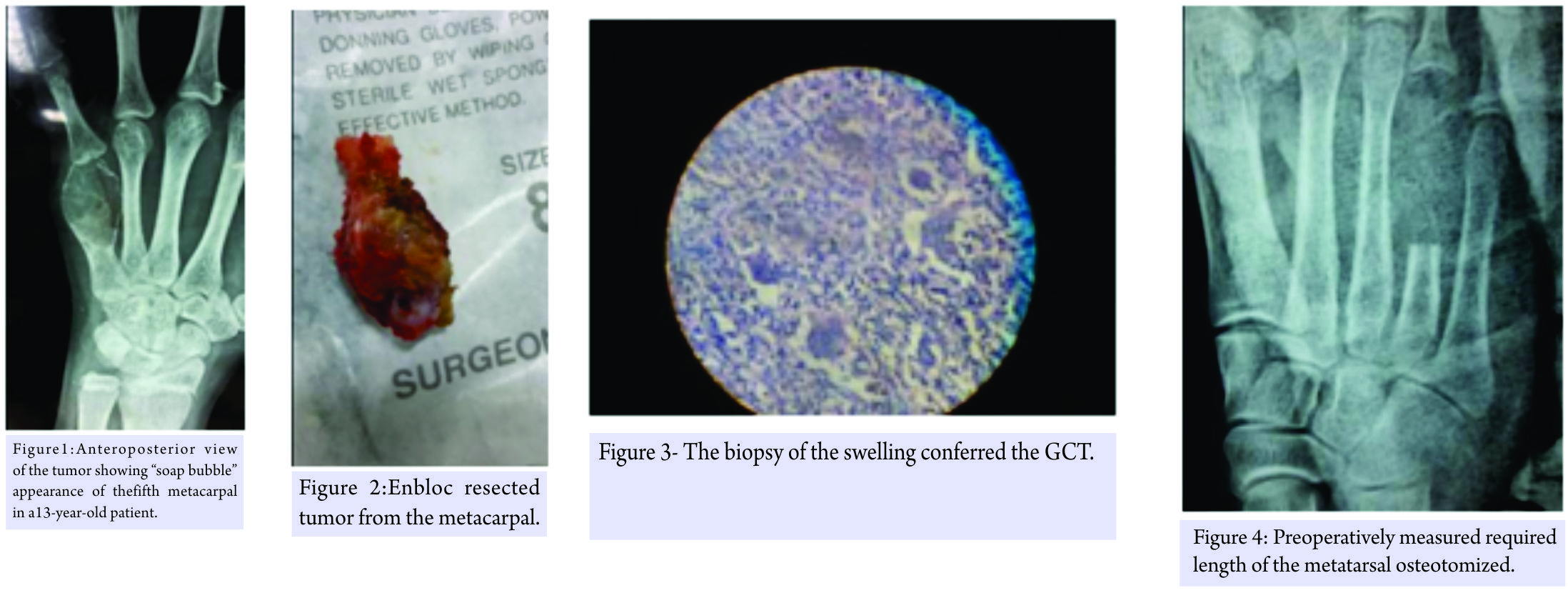

It is a case report of a 13-year-old girl appeared to the outpatient department with the history of swelling over her right hand for 5 months. It was gradually progressive in nature and situated over the dorsum and medial aspect of the hand. There was no history of trauma or such type of lesion elsewhere in the body or the in the family. There were no any associated features, i.e. pain, fever, or any sign or symptoms influencing her general health. On examination, there was a swelling, which was firm in consistency and occupying the dorsal and inner side of the fifth metacarpal. Local temperature was not raised and the skin was mobile and there was no any feature suggestive of inflammatory pathology. On deep palpation, it was tender and the range of movement was restricted. The routine hematological examination was within normal limit. The radiology revealed that there was an osteolytic fusiform expansible lesion involving to the whole distal 2/3rd of the fifth metacarpal and the articular surface too. The cortical is was paper thin, breached, inflated, and without the periosteal reaction (Fig. 1) and the tumor radiograph had “soap bubble” appearance. Hence, the provisional (clinicoradiological) diagnosis of aneurysmal bone cyst and GCT was conceded. The chest X-ray was also sought and it was within the normal limit. The core-cut biopsy sent and it conferred the diagnosis of GCT (Fig. 2).

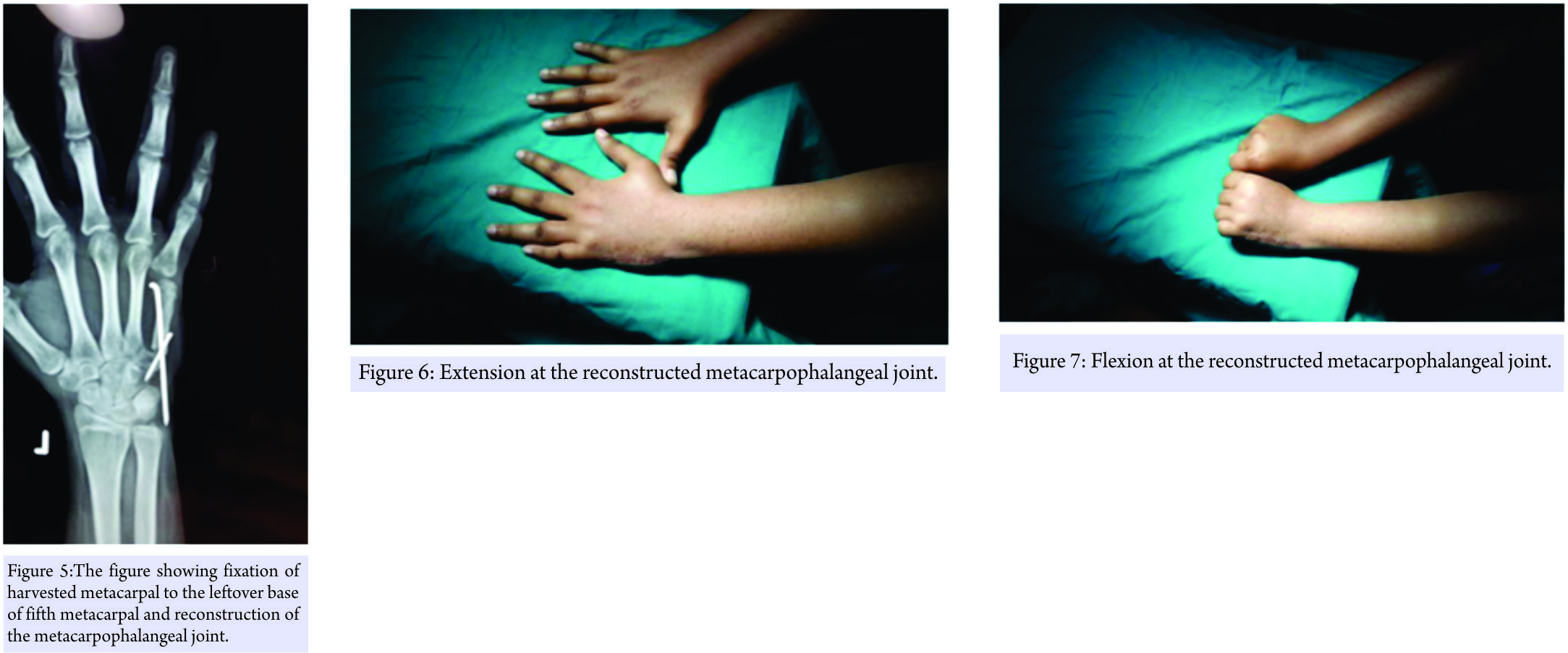

At each follow-up, the clinical and radiological assessment was done. The Union at the junction of the metatarsal and the base of the leftover metacarpal occurred in the 6 weeks and no obvious changes noticed at the transferred metatarsal. Initially, the movements had both extension and flexion lag, so the meanwhile electric stimulation given. At the end of the 6 months of follow-up, the movements are painless and almost up to normal except the terminally restricted at the flexion. It ranges from 0° to75° flexion at the metacarpophalangeal joint (Fig. 6 and 7). The patient was able to grasp any object and has pretty good grip strength. After the 2 years of follow-up, after the surgery, the procedure is fulfilling our expectations and corroborates the reliability of this method. During the initial follow-up, the patient had the mild-to-moderate pain over his foot while walking and unable to dorsiflex his fourth toe. However, now, she is free from pain or any complaint such as deformity or difficulty in walking. However, there is still slight weakness of fourth toe’s dorsiflexor. Finally, she is happy and has no any complaints.

Discussion

GCT comprise the 4–5% of the all primary bone tumors (and 20% of the benign bone tumors), but interestingly it is more among the Asiatic population, albeit in the China it constitutes the 20% of the all primary bone tumors [5, 6]. GCT is generally conceded as a benign entity, but it is more notorious for its unpredictable nature [7, 8]. The most common sites of the GCT of the bone are distal femur (75–90%) followed by the upper tibia (25%), distal end radius, and humerus [9]. The incidence of GCT in the hand bone has been reported from 1.7% to 4% (of all GCT) in the different literatures [10]. GCT of the hand has more aggressive tendency, so in the comparison to the GCT of the other long bones, the signs and symptoms appear more rapidly and even in the younger age group. Multicentricity (18%) and recurrence are the typical features of the GCT of hand, so the bone scan and radical treatments are recommendable [11]. GCT usually presents as swelling and pain. GCT typically affects the metaphyseal-epiphyseal or epiphyseal location. However, the suspicion arises if the lesion does not involve the epiphysis. Radiography is a supportive tool but not confirmatory. The clinical and radiological differentials include the aneurysmal bone cyst, nonossifying fibroma, and giant cell-rich osteosarcoma [12, 13, 14].However, in the skeletally immature patients, it interestingly occupies the metaphysis [15, 16]. A management protocol of the GCT has not been evolved very much in the past few decades due to the scarcity of the randomized control trial. Versatile modalities are available in the literatures for the management of the GCT of the hand bones, i.e., curettage, wide resection and reconstruction, amputation, and arthroplasty. Among the available surgical interventions, the curettage is most commonly performed surgery [17]. However, the management of the GCT of the hand bone by the curettage is a matter of contention. The natural history of the GCT of the hand seems alike to the traditional GCT of the rest of the bone. Because Wittig et al. stated that there was 75% recurrence rate in GCT of the hand bones if they had been treated by the curettage [18]. Moreover, it is much more than the other places, where the curettage has the recurrence of 10–20% [19]. Hence, for the management of the GCT of the metacarpal, wide resection with autograft replacement, arthroplastyor amputation are preferred modalities. In the chronicles, it was the littler that described the technique for metacarpal resection and replaced it by the graft obtained from the tibia [20]. Kotwal et al. managed the recurrent GCT of the second metacarpal by the vascularized joint transfer technique, but this is an assiduous and painstaking surgery and not easily feasible to be performed by every surgeon [21]. Manfrini et al. treated the recurrent GCT of the metacarpal by the autologous fibular graft with implant arthroplasty of the metacarpophalangeal joint and reported the excellent hand function after the 8years of the follow-up [22]. Various authors suggest also for the wide resection or ray amputation [23, 24]. Saikia et al. treated the two cases of GCT of the metacarpal by the ray amputation and the resection with replacement by the autologous tricortical iliac crest graft [25]. Cryotherapy and antiangiogenic therapy by interferon Alfa-2a also have been used by some authors [26]. GCT expresses the receptor activator of nuclear factor κB ligand (RANKL), which causes osteolysis of bone. Denosumab (human monoclonal antibody) has affinity as well as specificity to RANKAL and is effective to decrease the aggressive osteolytic nature of GCT. Hence, the denosumab is used as an option in unresectable GCT or to bypass the surgical procedures, which may cause morbidity [27]. Maini et al. proposed the management of GCT of the metacarpal by the transfer of autologous osteoarticular ligamentous complex of the fourth metatarsal in a single stage surgery. It was based on the assumption that the synovial layer of proximal phalanx endowed to the required nutrition of the cartilage and head of the metatarsal and secured the longevity of the graft [28]. Our procedure is also the facsimile to this surgery, with its rarity of occurrence in the skeletally immature patient. Furthermore, the metatarsal transfer is a technically easier surgery, entails esthetically and functionally average results, to which an average orthopedist can execute. Osteoarticular ligamentous graft has some advantages such as it remodels along the stress lines and its incorporation is permanent. However, it also has the potential disadvantages such as donor site morbidity and difficulty in recognizing the tumor recurrence.

Conclusion

Although the GCT of the bones has the affection to the Asian subcontinent, the incidence of it among the hand bones is sparse. Even then, the GCT of the metacarpal in skeletally immature patients is unexampled, as in this case. We are bringing it to the horizon of the literature to depict the clinical, radiological demeanor, and surgical as well as functional aftereffect. In the epilogue, the treatment was the befitting modality in our case and gave the well-turned results.

Clinical Message

GCT can be conceded as a clinical differential diagnosis of bony swelling even in the skeletally immature patient. Moreover, the free osteoarticular metatarsal transfer can be used as an option for GCT of the metacarpal.

References

1. Sharma V, Sharma S, Mistry KA, Awasthi B, Verma L, Singh U. Giant cell tumor of bone in skeletally immature patients-a clinical perspective. J Orthop Case Rep 2015;5:57-60.

2. Patel MT, Nayak MR. Unusual presentation of giant cell tumor in skeletally immature patient in diaphysis of Ulna. J Orthop Case Rep 2015;5:28-31.

3. Puri A, Agarwal MG, Shah M, Jambhekar NA, Anchan C, Behle S. Giant cell tumor of bone in children and adolescents. J PediatrOrthop 2007;27:635-9.

4. Al Lahham S, Al Hetmi T, Sharkawy M. Management of giant cell tumor occupying the 5th metacarpal bone in 6 years old child. Qatar Med J 2013;2013:38-41.

5. Gamberi G, Serra M, Ragazzini P, Magagnoli G, Pazzaglia L, Ponticelli F, et al.Identification of markers of possible prognostic value in 57 giant cell tumors of bone. Oncol Rep 2003;10:351-6.

6. Thomas DM, Skubitz T. Giant-cell tumour of bone. CurrOpinOncol 2009;21:338-44.

7. Pai SB, Lalitha RM, Prasad K, Rao SG, Harish K. Giant cell tumor of the temporal bone-a case report. BMC Ear Nose Throat Disord 2005;5:8.

8. Werner M. Giant cell tumour of bone: Morphological, biological and histogenetical aspects. Springer Verlag 2006;30:484-9.

9. Goldenberg RR, Campbell CJ, Bonfiglio M. Giant-cell tumor of bone. An analysis of two hundred and eighteen cases. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1970;52:619-64.

10. Unni KK, editor. Dahlin’s Bone Tumors: General Aspects and Data on 11087 Cases. 5th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott-Raven; 1996. p. 263-83.

11. Averill RM, Smith RJ, Campbell CJ. Giant-cell tumors of the bones of the hand. J Hand Surg Am 1980;5:39-50.

12. Utrecht VH. Giant cell tumors and aneurysmal bone cysts of spine. J Bone Joint Surg 1965;47:701.

13. Betsy M, Kupersmith LM, Springfield DS. Metaphyseal fibrous defects. J Am AcadOrthopSurg 2004;12:89-95.

14. Mirra JM. Bone Tumors: Clinical, Radiologic and Pathologic Correlations.Philadelphia, PA: Lea and Febiger; 1989. p. 326-31.

15. Kransdorf MJ, Sweet DE, Buetow PC, Giudici MA, Moser RP Jr. Giant cell tumor in skeletally immature patients. Radiology 1992;184:233-7.

16. Picci P, Manfrini M, Zucchi V, Gherlinzoni F, Rock M, Bertoni F, et al. Giant-cell tumor of bone in skeletally immature patients. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1983;65:486-90.

17. Balke M, Schremper L, Gebert C, Ahrens H, Streitbuerger A, Koehler G, et al. Giant cell tumor of bone: Treatment and outcome of 214 cases. J Cancer Res ClinOncol 2008;134:969-78.

18. Wittig JC, Simpson BM, Bickels J, Kellar-Graney KL, Malawer MM. Giant cell tumor of the hand: Superior results with curettage, cryosurgery, and cementation. J Hand Surg Am 2001;26:546-55.

19. Campanacci M. Bone and Soft Tissue Tumors. 2nded. New York, NY: Springer-Verlag; 1999.

20. Littler JW. Metacarpal reconstruction. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1947;29:723-37.

21. Kotwal PP, Nagaraj C, Gupta V. Vascularised joint transfer in the management of recurrent giant cell tumour of the second metacarpal. J Hand SurgEurVol 2008;33:314-6.

22. Manfrini M, Stagni C, Ceruso M, Mercuri M. Fibular autograft and silicone implant arthroplasty following resection of giant cell tumor of the metacarpal: A case report with 8 years follow-up. Orthopedics 2008;31:96.

23. Meena UK, Sharma YK, Saini N, Meena DS, Gahlot N. Giant cell tumours of hand bones: A report of two cases. J Hand Microsurg 2015;7:177-81.

24. Ozalp T, Yercan H, Okçu G, Ozdemir O, Coskunol E, Bégué T, et al. Giant cell tumour of hand: Midterm results in five patients. Rev ChirOrthopReparatriceAppar Mot 2007;93:842-7.

25. Saikia KC, Bhuyan SK, Ahmed F, Chanda D. Giant cell tumor of the metacarpal bones. Indian J Orthop 2011;45:475-8.

26. Yasko AW. Interferon therapy for giant cell tumor of bone. CurrOpinOrthop 2006;17:568-72.

27. Puri A, Agarwal M. Treatment of giant cell tumor of bone: Current concepts. Indian J Orthop 2007;41:101-8.

28. MainiL,CheemaGS,YuvarajanP,Gautam VK. Free osteoarticular metatarsal transfer for giant cell tumor of metacarpal-a surgical technique. J Hand Microsurg 2011;3:89-92.

|

|

|

|

| Dr. Pankaj Kumar Mishra | Dr. Yash Agrawal | Dr. Prakhar Singhal | Dr. Kripa Shankar Mishra |

| How to Cite This Article: Mishra PK, Agrawal Y, Singhal P, Mishra KS. Giant-cell Tumor of Metacarpal in the Skeletally Immature Patient and Free Osteoarticular Metatarsal Transfer- Review of Literature with Case Report. Journal of Orthopaedic Case Reports 2017 Sep-Oct ; 7(5): 20-23 |

[Full Text HTML] [Full Text PDF] [XML]

[rate_this_page]

Dear Reader, We are very excited about New Features in JOCR. Please do let us know what you think by Clicking on the Sliding “Feedback Form” button on the <<< left of the page or sending a mail to us at editor.jocr@gmail.com