[box type=”bio”] Learning Point for this Article: [/box]

Possibility of the spontaneous reduction of elbow dislocation should be kept in mind and care must be taken that the medial epicondyle may be in the joint space in pediatric patients.

Case Report | Volume 8 | Issue 1 | JOCR Jan – Feb 2018 | Page 8-10| Serdar Demiroz, Sevki ERDEM. DOI: 10.13107/jocr.2250-0685.974

Authors: Serdar Demiroz[1], Sevki ERDEM[2]

[1]Department of Orthopaedics and Traumatology, Bingöl State Hospital, Bingöl, Turkey.

[2]Department of Orthopaedics and Traumatology, Emsey Hospital, Istanbul, Turkey.

Address of Correspondence:

Dr. Serdar Demiroz,

Department of Orthopaedics and Traumatology, Bingöl State Hospital, Bingöl, Turkey.

E-mail: serdardemiroz@hotmail.com

Abstract

Introduction: Elbow dislocation accounts 3–6% of all pediatric elbow injuries. Medial epicondyle is the most common fracture related to the elbow dislocation in pediatric population. About 15–18% of medial epicondyle fractures related to dislocation present with the incarceration of medial epicondyle in the elbow joint after reduction. This situation is the only absolute surgical indication for epicondyle fracture in this population.

Case Report: A 15-year-old male children admitted to the emergency department with swelling, pain, and limitation of elbow range of motion after falling off a horse. Plain radiographs of the elbow revealed incongruity and increase in joint space of the elbow. When looked at carefully the medial epicondyle was seen not in the anatomic position but in the joint.

Urgent surgery was performed. The medial epicondyle was removed from the joint and fixed its position with a 4 mm diameter cannulated lag screw, under fluoroscopy control. Then, the tear of the origin of flexor muscle groups on medial epicondyle was repaired with a 5.5 mm suture anchor.

Conclusion: Due to the well-established association between elbow dislocation and incarcerated medial epicondyle fracture, it is easy to address the entrapment of bone fragment into the joint if any suspicion exists after reduction. However, spontaneous reduction of elbow dislocation is also possible, and it leads to the challenge of diagnosis. Due to that reason, surgeon must suspect the possibility of medial epicondyle entrapment if there is gross swelling, crepitation, and limitation of elbow range of motion although there is no dislocation.

Keywords: Medial epicondyle, entrapment, elbow dislocation, incarceration.

Introduction

Elbow dislocation is rare in pediatric population. It accounts only 3–6% of all pediatric elbow injuries [1]. It is mostly posterolateral direction and so it leads to tension on the MCL which originates from medial epicondyle. Furthermore, medial epicondyle is the last ossification center of the distal humerus [1, 2]. As a result, medial epicondyle is the most common fracture related to the elbow dislocation in pediatric population [3]. 50% of medial epicondyle fractures related to elbow dislocation in this population, and 15–18% of these present with the incarceration of medial epicondyle in the elbow joint after reduction [4]. It is very important to realize this case to prevent some potential complications such as pain, instability, and limitation of range of motion. Therefore, surgeon should be aware of this potential complication, and if there is suspicion of incarcerated medial epicondyle, it is an absolute indication for urgent surgery.

Otherwise, elbow dislocation and incarcerated medial epicondyle fracture association is well established in the literature, so if there is a dislocation, it is easier to address entrapment, but sometimes elbow dislocations can be reduced spontaneously, so when patient admitted to emergency department, there is no dislocation, so it leads to the challenge of diagnosis of incarcerated medial epicondyle.

We present a case report of a patient admitted to the emergency department with incarcerated medial epicondyle within the dislocated but spontaneously reduced elbow.

Case Report

A 15-year-old male child admitted to the emergency department with swelling, pain, and limitation of elbow range of motion after falling off a horse. On examination, there was gross sensitivity with palpation and swelling. Elbow range of motion was painful and limited; crepitation was also detected. Neurovascular examination and adjacent joints were normal. Varus and valgus stress tests could not be applied because of gross swelling and pain.

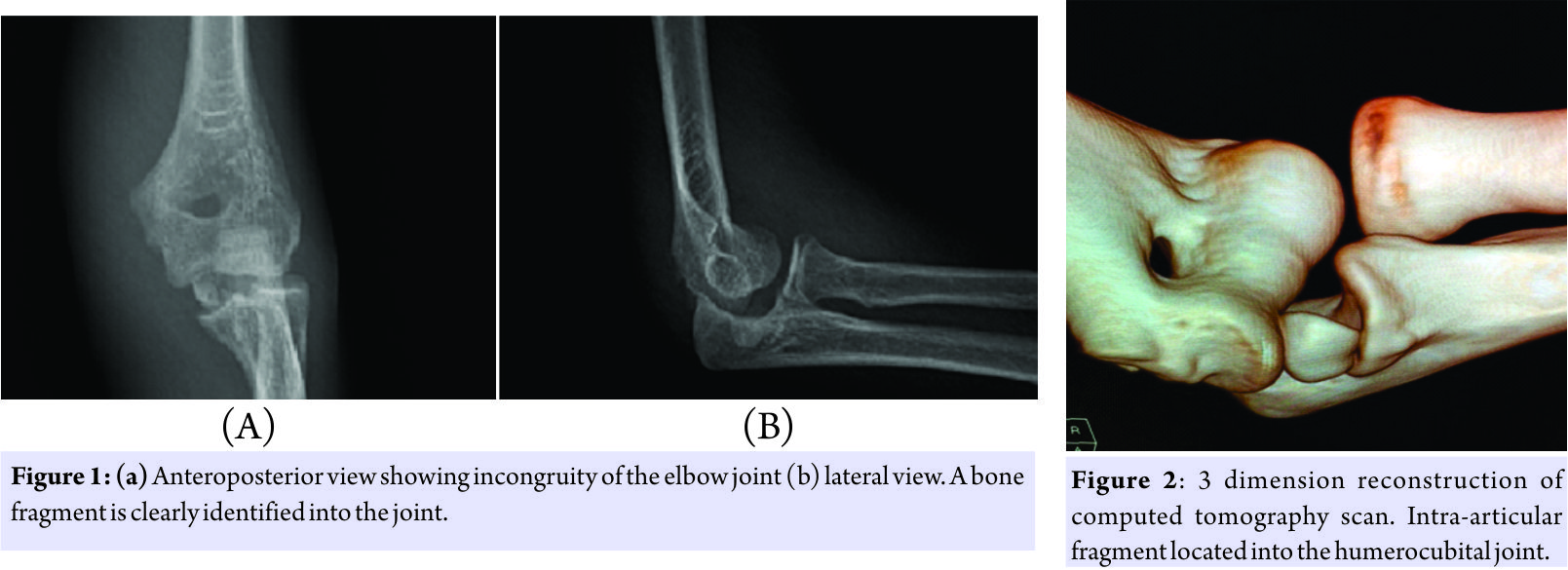

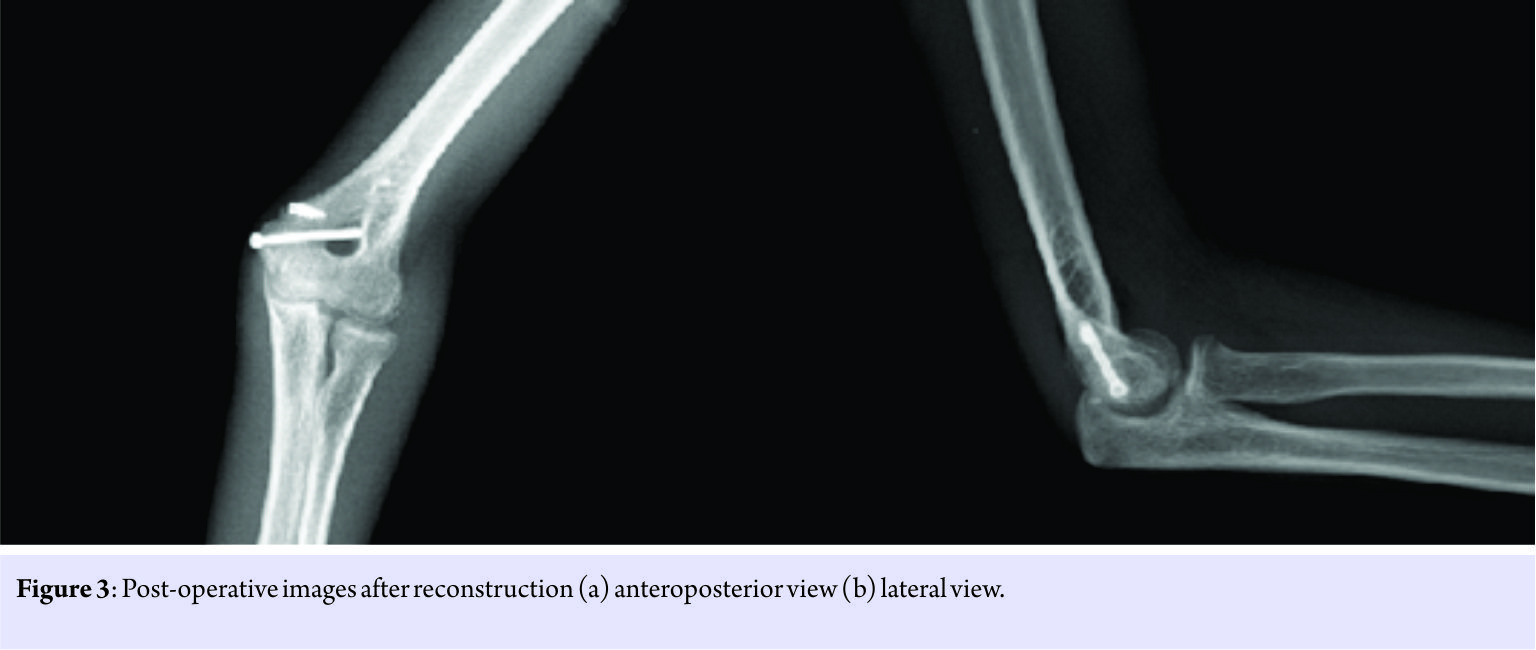

Plain radiographs of the elbow revealed incongruity and increase in joint space of the elbow. The medial epicondyle was not in the anatomic position and a bone fragment was present in the joint (Fig. 1). At this moment, it was obvious that elbow dislocated and reduced spontaneously and medial epicondyle entrapped within the joint. A computed tomography (CT) scan was performed to see if any other pathology was present. Incarcerated medial epicondyle was seen easily in 3 dimension CT scan (Fig. 2).

Urgent surgery was performed. The patient was placed in supine position under general anesthesia. Tourniquet was used after prophylactic antibiotic administration, and medial approach was performed. The ulnar nerve is identified and protected. The medial epicondyle was removed from the joint and fixed its position with a 4 mm diameter cannulated lag screw, under fluoroscopy control. Perioperative testing revealed flexion, extension, and varus stability but valgus instability because of the tear of the origin of flexor muscle groups on medial epicondyle, so a 5.5 mm suture anchor was placed next to the epicondyle and the tear was repaired (Fig. 3). Postoperatively, a posterior above-elbow splint with the elbow joint in 90° of flexion and neutral rotation was applied for 10 days followed by an early motion. At 3 months of follow–up, the patient had almost full range of motion with only a lack of 10°of extension, and at 6 months, he had full range of motion with no pain and instability in the entire range of motion and varus and valgus stress.

Discussion

Elbow dislocations are less frequent in children than in adults, and most frequently, they are toward to the posterolateral. If there is no fracture associated with dislocation, it is called simple, and otherwise, it is called complex dislocation. Urgent reduction and immobilization are the standard procedure for all types of dislocation. However, if there is instability in elbow joint or displaced fracture, it needs surgery. Posterolateral dislocation creates pressure on MCL, and it is ruptured in adult, but it leads to Salter-Harris Type 1 fracture of medial epicondyle in children. Medial epicondyle is a small fragment, so it is difficult to see in plain radiographs and it also may be confused with the ossification centers of trochlea or olecranon. However, due to the well-defined association between elbow dislocation and medial epicondyle fracture in the literature, it is easy to address this fracture when there is a dislocated elbow in children, but if it is reduced spontaneously like in this case, surgeon may overlook the presence of dislocation, and it may be possible to cannot detect entrapped small fragment. Management of medial epicondyle fracture is controversial. Although some authors have advocated open reduction and internal fixation in all cases [5], others have considered surgery only for the entrapped or displaced epicondyle to restore stability to the elbow [6, 7, 8]. Amount of displacement for surgery is also controversial. Hines et al. [9] suggested surgical treatment for medial epicondyle fractures with a displacement of more than 2 mm, although Fowles et al. [10] reported good results with conservative treatment even in the presence of displacement more than 2 mm. On the other hand, Kobayashi et al. [11] highlighted the significance of the size of the fragment in epicondyle fractures and suggested that conservative treatment is indicated for patients in whom the maximum diameter of bone fragment is 13 mm. Whatever the amount of displacement or size of the fragment, the only absolute indication for surgery is entrapment of the fragment in the joint. Delay in the diagnosis of this injury can occur because of lack of interpretation of the radiographs and can lead to serious clinical and legal problems. There should be a high index of suspicion with good clinical examination and careful assessment of the radiographs.

Conclusion

Elbow dislocations in children are uncommon, but associated injuries can be important and must be suspected. Especially, medial epicondyle fracture is common with dislocations. Dislocations can be reduced spontaneously, so although there is no dislocation when the patient admitted to the emergency room, the surgeon must suspect the possibility of spontaneous reduction and medial epicondyle entrapment if there is gross swelling, crepitation, and limitation of elbow range of motion and incongruity of joint space on plain radiograph.

Clinical Message

Medial epicondyle fracture is common with elbow dislocations, and dislocations can be reduced spontaneously, so although there is no dislocation when the patient admitted to the emergency room, the surgeon must suspect the possibility of spontaneous reduction and medial epicondyle entrapment if there is gross swelling, crepitation, and limitation of elbow range of motion.

References

1. Wilkins KE. Fractures and dislocations of the elbow region. In: Rockwood CA, Wilkins KE, King R, editors. Fractures İn Children. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott; 1991. p. 618-54.

2. Gottschalk HP, Eisner E, Hosalkar HS. Medial epicondyle fractures in the pediatric population. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 2012;20:223-32.

3. Price CT, Flynn JM. Management of fractures. In: Morrissy RT, Weinstein SL, editors. Lovell & Winter’s Pediatric Orthopaedics. 6th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2006. p. 1430-516.

4. Beaty JH, Kasser JH, editors. The elbow-physeal fractures, apophyseal injuries of the distal humerus, osteonecrosis of the trochlea, and T-condylar fractures. In: Rockwood & Wilkins’ Fractures in Children. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2005. p. 628-42.

5. Schwab GH, Bennett JB, Woods GW, Tullos HS. Biomechanics of elbow instability: The role of the medial collateral ligament. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1980;146:42-52.

6. Fowles JV, Slimane N, Kassab MT. Elbow dislocation with avulsion of the medial humeral epicondyle. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1990;72:102-4.

7. Carlioz H, Abols Y. Posterior dislocation of the elbow in children. J Pediatr Orthop 1984;4:8-12.

8. Roberts PH. Dislocation of the elbow. Br J Surg 1969;56:806-15.

9. Hines RF, Herndon WA, Evans JP. Operative treatment of medial epicondyle fractures in children. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1987;223:170-4.

10. Fowles JV, Kassab MT, Moula T. Untreated intra-articular entrapment of the medial humeral epicondyle. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1984;66:562-5.

11. Kobayashi Y, Oka Y, Ikeda M, Munesada S. Avulsion fracture of the medial and lateral epicondyles of the humerus. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2000;9:59-64.

|

|

| Dr. Serdar Demiroz | Dr. Sevki ERDEM |

| How to Cite This Article: Demiroz S, Sevki ERDEM. Spontaneous Reduction of Elbow Dislocation with Entrapment of Medial Epicondyle in Children: A Case Report. Journal of Orthopaedic Case Reports 2018 Jan-Feb; 8(1): 8-10 |

[Full Text HTML] [Full Text PDF] [XML]

[rate_this_page]

Dear Reader, We are very excited about New Features in JOCR. Please do let us know what you think by Clicking on the Sliding “Feedback Form” button on the <<< left of the page or sending a mail to us at editor.jocr@gmail.com