[box type=”bio”] Learning Point of the Article: [/box]

Magnetic resonance imaging should be performed before arthroscopic surgery to rule out aneurysm, especially in a patient with aseptic ankle and/or a history of infective endocarditis.

Case Report | Volume 8 | Issue 6 | JOCR November – December 2018 | Page 68-73 | Ichiro Tonogai, Hiroki Arase, Yutaka Kawabata, Koichi Sairyo. DOI: 10.13107/jocr.2250-0685.1264

Authors: Ichiro Tonogai[1], Hiroki Arase[2], Yutaka Kawabata[3], Koichi Sairyo[1]

[1]Department of Orthopedics, Institute of Biomedical Science, Tokushima University Graduate School, 3-18-15 Kuramoto, Tokushima 770-8503, Japan.

[2]Department of Cardiovascular Surgery, Institute of Biomedical Science, Tokushima University Graduate School, 3-18-15 Kuramoto, Tokushima 770-8503, Japan.

[3]Department of Cardiovascular Medicine, Institute of Biomedical Science, Tokushima University Graduate School, 3-18-15 Kuramoto, Tokushima 770-8503, Japan.

Address of Correspondence:

Dr. Koichi Sairyo,

Department of Orthopedics, Institute of Health Biosciences, Tokushima University Graduate School, 3-18-15 Kuramoto, Tokushima 770-8503, Japan.

E-mail: sairyokun@hotmail.com

Abstract

Introduction: Introduction: There have been reports of true aneurysm of the posterior tibial artery, but only three reports have described true aneurysm of the posterior tibial artery at the ankle, and there has been only one report of tarsal tunnel syndrome caused by true aneurysm of this artery. In this case report, we describe a rare case of true septic aneurysm of the posterior tibial artery presenting as tarsal tunnel syndrome which was found after anterior arthroscopic debridement of a septic ankle in a 55-year-old man.

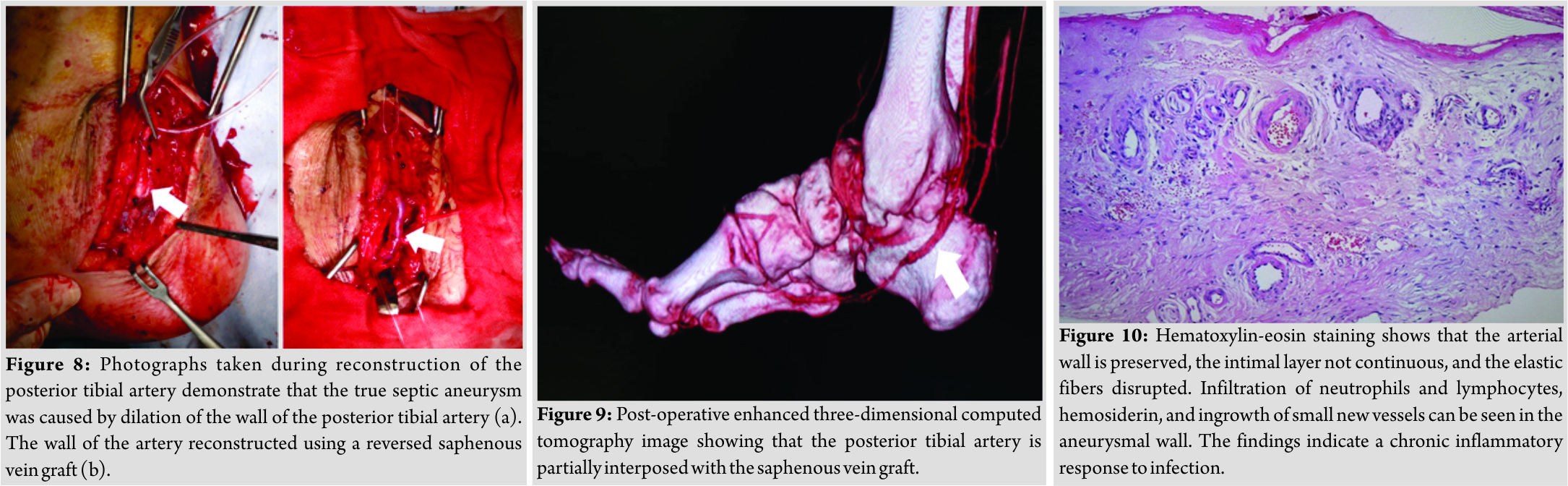

Case Report: 13 years earlier, this patient had undergone aortic valve replacement for severe aortic regurgitation caused by infective endocarditis with aortic valve vegetations. Since then, the patient had been treated with the oral anticoagulant warfarin. The aneurysm was successfully treated by a saphenous vein graft and administration of antibiotics. The patient likely developed septic ankle and aneurysm as a consequence of infective endocarditis.

Conclusions: Magnetic resonance imaging should be performed before arthroscopic surgery to rule outaneurysm, especially in a patient with a septic ankle and/ora history of infective endocarditis.

Keywords: Anterior arthroscopy, infective endocarditis, posterior tibial artery, septic ankle, tarsal tunnel syndrome, true septic aneurysm.

Introduction

The incidence of joint sepsis has been estimatedas2–10 per 10,000 individuals annually [1]. The knee is the most common site of septic arthritis, followed by the shoulder, hip, and ankle [2]. Sepsis involving the ankle joint is rarer, accounting for only 3.4%–7% of all cases [3, 4, 5].The most common causative organism in a septic ankle joint is Staphylococcus [6, 7]. Infrapopliteal aneurysms are uncommon but often appear as false aneurysms associated with trauma, infection, iatrogenic injury, changes in the collagen matrix, and inflammation [8, 9, 10, 11, 12]. True aneurysms of the posterior tibial artery are rare [13, 14, 15, 16, 17]. True aneurysms around the ankle are even rarer, with only three cases described in the English language literature [18, 19, 20]. Here, we describe the rare case of a 55-year-old man with tarsal tunnel syndrome and a history of surgery for infective endocarditis who was found to have a true septic aneurysm of the posterior tibial artery after anterior arthroscopic debridement of a septic ankle joint using standard anteromedial and anterolateral portals, in whom a reversed saphenous vein graft was successfully performed to reconstruct the damaged posterior tibial artery.

Case Report

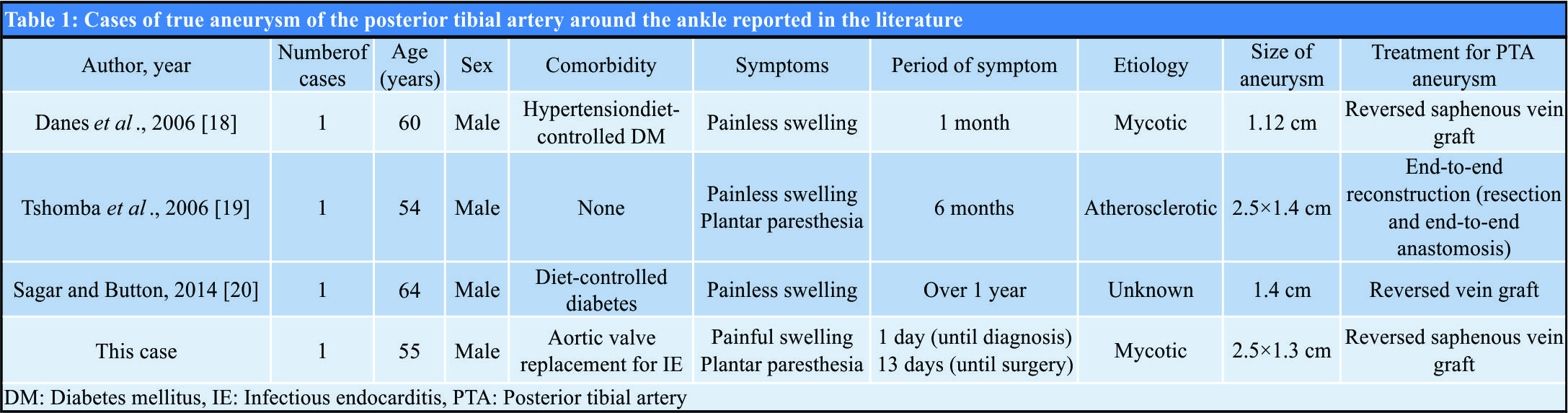

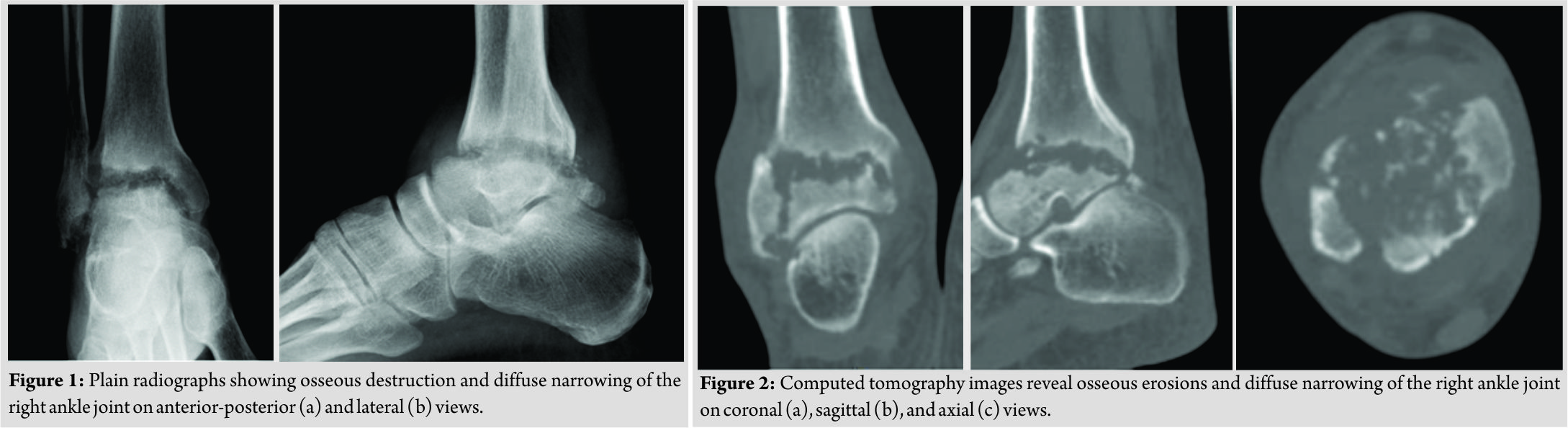

A 55-year-old man presented to our university hospital complaining of general fatigue for the past several months. 13 years earlier, he had undergone aorta valve replacement at our hospital for severe aortic regurgitation caused by infective endocarditis with aortic valve vegetations and had been receiving oral warfarin as an anticoagulant since that time. He was 167 cm tall, weighed 60 kg, and had a body mass index of 21.7. Laboratory investigations revealed severe anemia with hemoglobin of 4.4 g/dL, so he was admitted to the internal medicine department of our hospital for blood transfusion. He also reported a 5-year history of untreated right ankle pain that had worsened in the previous month. During this hospitalization, he was referred to our department for the assessment of the right ankle pain. On physical examination, there were tenderness, local warmth, and redness over the right ankle, especially on the anterior aspect, and range of motion at the ankle joint was limited to 0°of dorsiflexion and 5° of plantarflexion. Laboratory investigations revealed evidence of inflammation(white blood cell count 8600 cells/µL and C-reactiveprotein 8.44 mg/dL). Clinical examination showed no feature ssuggestive of congenital connective tissue disorder. Radiography and computed tomography images revealed osseous destruction and diffuse narrowing of the right ankle joint space (Fig. 1a and b and Fig. 2a, b, c).

Discussion

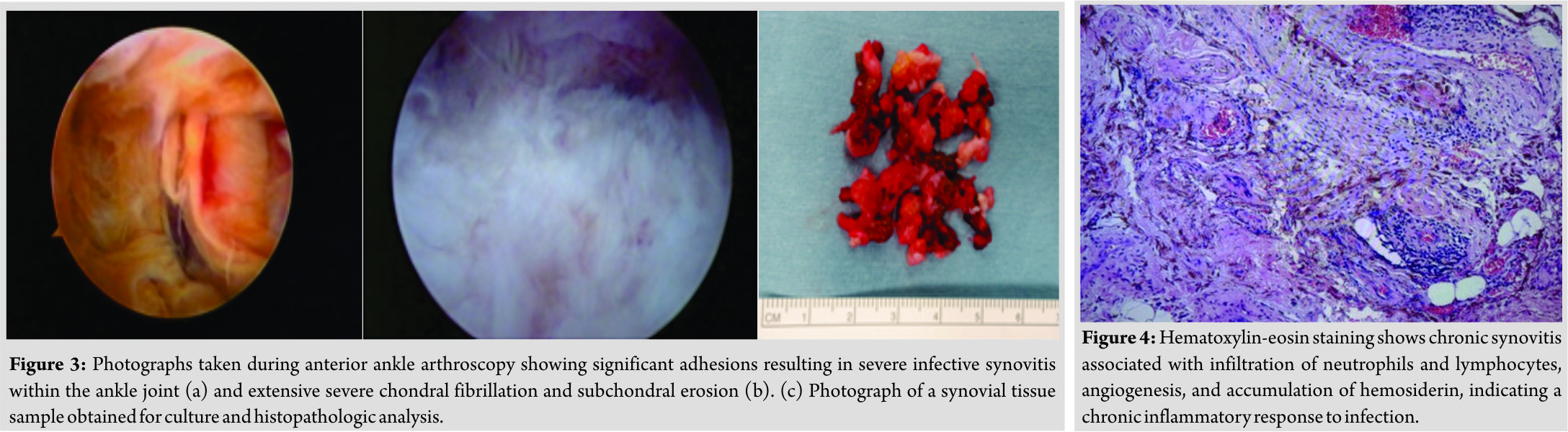

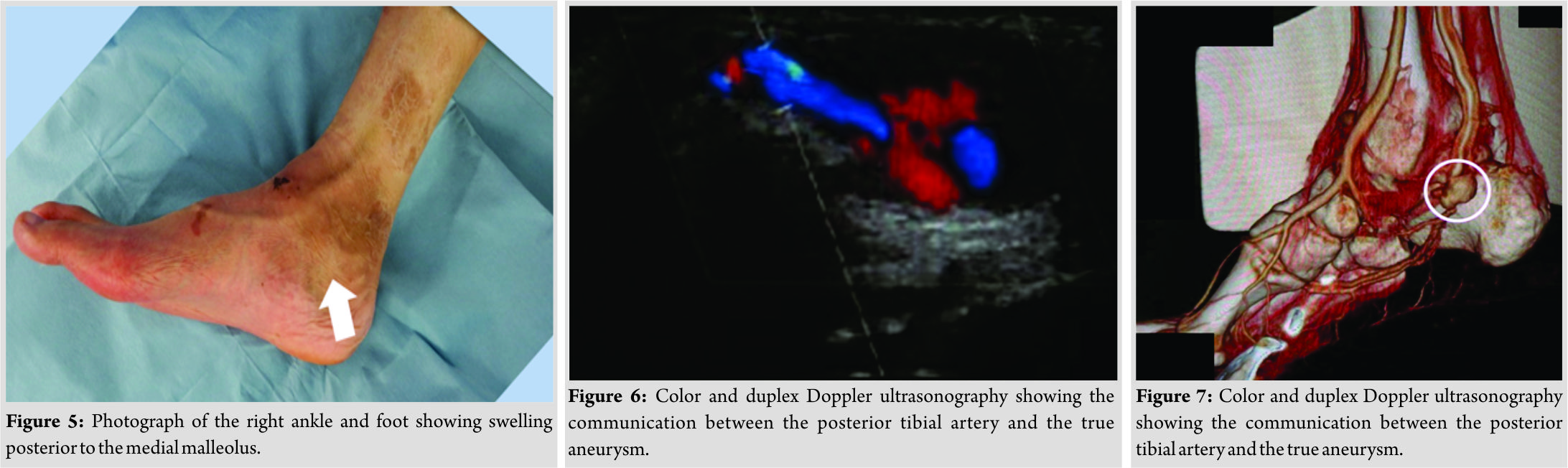

To the best of our knowledge, only three cases of true aneurysm of the posterior tibial artery at the ankle have been reported in the literature (Table 1) [18, 19, 20]. Our patient also had peripheral neuropathy, similar to tarsal tunnel syndrome, because of compression of the tibial nerve within the tarsal tunnel by a true septic aneurysm. The main etiologic causes of tarsal tunnel syndromes are the presence of a ganglion, osseous prominence with tarsal bone coalition, trauma, varicose veins, neuroma, hypertrophy of the flexor retinaculum, foot deformities, and idiopathic [21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27]. Recently, there have been reports of tarsal tunnel syndrome caused by pseudoaneurysm [28], suture material [29], posterior tibial vein aneurysm [30], aneurysm of a branch of the posterior tibial artery [31], and a perforating branch from the posterior tibial artery [32]. However, to the best of our knowledge, only one case of tarsal tunnel syndrome caused by true aneurysm of the posterior tibial artery, which showed a positive Tinel’s-like sign similar to our case, has been described in the literature (Table 1) [19]. Open arthrotomy is often needed to effectively eradicate infection in a septic joint [4,5]. However, arthroscopy allows a direct magnified view of the intra-articular anatomy, joint lavage, synovectomy of septic pannus formation without the morbidity of extensive surgical incisions, more rapid recovery, and a lower incidence of iatrogenic injury, with outcomes similar to those of the more traditional open approach and fewer complications [33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38]. Therefore, we opted to perform arthroscopic surgery to treat the septic ankle in our case. Arthroscopic surgery with concomitant antibiotics might be an acceptable treatment method for this condition. Infection weakens the arterial wall and an infected aneurysm enlarges [39, 40]. Infected aneurysms are one of the most serious complications of infective endocarditis [41]. The incidence of infected aneurysm is approximately 0.9%–1.3% among all cases of arterial aneurysm [42, 43]. Staphylococcus species are the most common pathogens involved in an infected aneurysm [43]. In this study, Staphylococcus species was detected in the ankle. Therefore, in a patient with endocardial vegetations, an infected embolus might be carried to the posterior tibial artery and the ankle joint, and the posterior tibial artery might enlarge as a result of bacterial invasion. Anderson et al. [44] and Johnson et al. [45] reported that arterial repair or vein grafting should be avoided when treating septic aneurysm because of a high incidence of persistent infection and late rupture. However, Patel et al.[46] and Sakai et al. [31] reported that autologous vein graft could be used to bypass an excised aneurysm, although infection-related graft failure remains a significant complication. Our patient had a very serious medical condition and there was a high probability of rupture of the aneurysm. Therefore, we performed a vein graft and kept the patient on long-term antibiotic therapy, as recommended by Patel et al. [46]. Fichelle et al.[47] and Heyd et al.[48] reported that medical treatment for an infected aneurysm requires at least 6 weeks of appropriate parenteral and/or oral antimicrobial therapy, and we treated our patient accordingly. In our patient, inflammatory markers, white cell count and C-reactive protein, remain within normal limits, indicating no recurrence until his death due to acute ruptured infectious intracranial aneurysm. One of the limitations of this case report was the short follow-upperiod. At present, the patient is stable, the septic ankle is settled, but extensive open ankle debridement may be needed in the future. Another limitation is that magnetic resonance imaging was not performed before arthroscopic surgery. The aneurysm seemed to be preexisting and enlarged only after he supported his full body weight on the right foot. Due to thrombus or septic embolism at the distal level of the septic true aneurysm of the posterior tibial artery. In retrospect, we should have obtained magnetic resonance images before ankle arthroscopic surgery to check for aneurysm, given that the patient had a septic ankle joint and a history of infective endocarditis. Moreover, we should have taken brain MR images because cerebral complications are still frequent, occurring in up to 30% of infectious endocarditis patients, with stroke complicating 12% of endocarditis cases [49, 50, 51], and mortality approaches 80% in patients with ruptured infectious intracranial aneurysm [52].

Conclusion

We have encountered a rare case of true septic aneurysm of the posterior tibial artery found after anterior arthroscopic debridement of a septic ankle in a 55-year-old man who presented with tarsal tunnel syndrome and had undergone aortic valve replacement for severe aortic regurgitation caused by infective endocarditis with aortic valve vegetations 13 years earlier and had been receiving anticoagulant therapy since then. The aneurysm was successfully treated by a saphenous vein graft.

Acknowledgement

This study was supported in part by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan (17K16694 to I.T.).

Clinical Message

Magnetic resonance imaging should be performed before arthroscopic surgery to rule out aneurysm, especially in a patient with a septic ankle and/or a history of infective endocarditis.

References

1. Kaandorp CJ, Dinant HJ, van de Laar MA, Moens HJ, Prins AP, Dijkmans BA, et al. Incidence and sources of native and prosthetic joint infection: A community based prospective survey. Ann Rheum Dis 1997;56:470-5.

2. Esterhai JL Jr., Gelb I. Adult septic arthritis. Orthop Clin North Am 1991;22:503-14.

3. Newman JH. Review of septic arthritis throughout the antibiotic era. Ann Rheum Dis 1976;35:198-205.

4. Stutz G, Kuster MS, Kleinstück F, Gächter A. Arthroscopic management of septic arthritis: Stages of infection and results. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2000;8:270-4.

5. Vispo Seara JL, Barthel T, Schmitz H, Eulert J. Arthroscopic treatment of septic joints: Prognostic factors. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2002;122:204-11.

6. Lee CH, Chen YJ, Ueng SW, Hsu RW. Septic arthritis of the ankle joint. Chang Gung Med J 2000;23:420-6.

7. Holtom PD, Borges L, Zalavras CG. Hematogenous septic ankle arthritis. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2008;466:1388-91.

8. Mönig SP, Walter M, Sorgatz SS, Erasmi H. True infrapopliteal artery aneurysms: Report of two cases and literature review. J Vasc Surg 1996;24:276-8.

9. Loose HW, Haslam PJ. The management of peripheral arterial aneurysms using percutaneous injection of fibrin adhesive. Br J Radiol 1998;71:1255-9.

10. Mahmood A, Salaman R, Sintler M, Smith SR, Simms MH, Vohra RK. Surgery of popliteal artery aneurysms: A 12-year experience. J Vasc Surg 2003;37:586-893.

11. Kumar S, Shreeram K, Agarwal SK. Endovascular management of a posterior tibial artery aneurysm in type IV Ehlers–Danlos syndrome. EJVES Extra 2004;7:74-5.

12. Kanaoka T, Matsuura H. A true aneurysm of the posterior tibial artery: A case report. Ann Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2004;10:317-8.

13. Mukherjee D. Posterior approach to the peroneal artery. J Vasc Surg 1994;19:174-8.

14. Barbano B, Gigante A, Zaccaria A, Polidori L, Martina P, Schioppa A, et al. True posterior tibial artery aneurysm in a young patient: Surgical or endovascular treatment? BMJ Case Rep 2009. DOI: org/10.1136/bcr.04.2009.1812.

15. Zaraca F, Ponzoni A, Stringari C, Ebner JA, Giovannetti R, Ebner H, et al. The posterior approach in the treatment of popliteal artery aneurysm: Feasibility and analysis of outcome. Ann Vasc Surg 2010;24:863-70.

16. Ferrero E, Ferri M, Viazzo A, Gaggiano A, Berardi G, Piazza S, et al. Rupture of a true giant aneurysm of the posterior tibial artery: A huge size of 6 cm on diameter. Ann Vasc Surg 2010;24:1134.e9-13.

17. Murakami H, Izawa N, Miyahara S, Kadowaki T, Morimoto N, Morimoto Y, et al. A true aneurysm of posterior tibial artery. Ann Vasc Surg 2011;25:980.e1-2.

18. DanesSG, DreznerAD, TamimPM.Posterior tibial artery aneurysm: A case report. Vasc Endovasc Surg 2006;40:328-30.

19. Tshomba Y, Papa M, Marone EM, Kahlberg A, Rizzo N, Chiesa R. A true posterior tibial artery aneurysm–a case report. Vasc Endovasc Surg 2006;40:243-9.

20. Sagar J, Button M. Posterior tibial artery aneurysm: A case report with review of literature. BMC Surg 2014;14:37.

21. Edwards WG, Lincoln CR, Bassett FH 3rd, Goldner JL. The tarsal tunnel syndrome. Diagnosis and treatment. JAMA 1969;207:716-20.

22. Di Stefano V, Sack JT, Whittaker R, Nixon JE. Tarsal-tunnel syndrome. Review of the literature and two case reports. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1972;88:76-9.

23. Wilemon WK. Tarsal tunnel syndrome. Orthop Rev 1979;8:111-7.

24. Lau JT, Daniels TR. Tarsal tunnel syndrome: A review of the literature. Foot Ankle Int 1999;20:201-9.

25. Satoh K, Kanazawo N, Egawa M. Clinical study on tarsal tunnel syndrome. Seikei-Geka 1986;37:271-9.

26. Radin EL. Tarsal tunnel syndrome. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1983;181:167-70.

27. Ferraresi S, Leidi P, Leidi M, Ubiali E, Bortolotti G, Cassinari V, et al. Tarsal tunnel syndrome. Report of a case and review of clinical and surgical aspects. Ital J Neurol Sci 1992;13:47-51.

28. Park SE, Kim JC, Ji JH, Kim YY, Lee HH, Jeong JJ, et al. Post-traumatic pseudoaneurysm of the medial plantar artery combined with tarsal tunnel syndrome: Two case reports. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2013;133:357-60.

29. Norbury JW, Warren KM, Moore DP. Tarsal tunnel syndrome secondary to suture material within the tibial artery: A sonographic diagnosis. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 2014;93:361.

30. Ayad M, Whisenhunt A, Hong E, Heller J, Salvatore D, Abai B, et al.Posterior tibial vein aneurysm presenting as tarsal tunnel syndrome. Vascular 2015;23:322-6.

31. Sakai H, Miki T, Tamai K, Yamato M, Saotome K. Nontraumatic aneurysm of a branch of the posterior tibial artery mimicking a schwannoma. Magn Reson Med Sci 2002;1:233-6.

32. Kosiyatrakul A, Luenam S, Phisitkul P. Tarsal tunnel syndrome associated with a perforating branch from posterior tibial artery: A case report. Foot Ankle Surg 2015;21:e21-2.

33. Parisien JS, Shaffer B. Arthroscopic management of pyarthrosis. Clin Orthop 1982;275:243-7.

34. Broy SB, Stulberg SD, Schmid FR. The role of arthroscopy in the diagnosis and management of the septic joint. Clin Rheum Dis 1986;12:489-500.

35. Jerosch J, Hoffstetter I, Schröder M, Castro WH. Septic arthritis: Arthroscopic management with local antibiotic treatment. Acta Orthop Belg 1995;61:126-34.

36. Morgan DS, Fisher D, Merianos A, Currie BJ. An 18 year clinical review of septic arthritis from tropical Australia. Epidemiol Infect 1996;117:423-8.

37. Titov AG, Nakonechniy GD, Santavirta S, Serodobintzev MS, Mazurenko SI. Arthroscopic operations in joint tuberculosis. Knee 2004;1:57-62.

38. Ayral X. Arthroscopy and joint lavage. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 2005;19:401-15.

39. Stengel A, Mycotic WC. (Bacterial) aneurysms of intravascular origins. Arch Int Med 1923;31:527-54.

40. Mieno S, Ozawa H, Tanigawa J, Kurisu Y, Katsumata T. A surgical case of excision of infected aneurysm arising from anterior interosseal artery following infectious endocarditis. J Vasc Surg 2011;53:1104-6.

41. Watanabe N, Bandoh S, Ishii T, Negayama K, Kadowaki N, Yokota K. Infective endocarditis and infected aneurysm caused by Streptococcus dysgalactiae subsp. Equisimilis: A case report. Clin Case Rep 2017;5:187-92.

42. Chan FY, Crawford ES, Coselli JS, Safi HJ, Williams TW Jr. In situ prosthetic graft replacement for mycotic aneurysm of the aorta. Ann Thorac Surg 1989;47:193-203.

43. Müller BT, Wegener OR, Grabitz K, Pillny M, Thomas L, Sandmann W. Mycotic aneurysms of the thoracic and abdominal aorta and iliac arteries: Experience with anatomic and extra-anatomic repair in 33 cases. J Vasc Surg 2001;33:106-13.

44 Anderson CB, Butcher HR Jr., Ballinger WF. Mycotic aneurysms. Arch Surg 1974;109:712-7.

45. Johnson JR, Ledgerwood AM, Lucas CE. Mycotic aneurysm. New concepts in therapy. Arch Surg 1983;118:577-82.

46. Patel S, D’Souza N, Gurjar S, Hewes J, Edrees W. Mycotic aneurysm of the posterior tibial arteryda rare complication of bacterial endocarditis: A case report. J Med Case Rep 2008;2:341.

47. Fichelle JM, Tabet G, Cormier P, Farkas JC, Laurian C, Gigou F, et al. Infected infrarenal aortic aneurysms: When is in situ reconstruction safe? J Vasc Surg 1993;17:635-45.

48. Heyd J, Meallem R, Schlesinger Y, Rudensky B, Hadas-Halpern I, Yinnon AM, et al. Clinical characteristics of patients with psoas abscess due to nontyphiSalmonella. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 2003;22:770-3.

49. Cavassini M, Meuli R, Francioli P. Complications of infectious endocarditis. In: Scheld WM, Whitley RJ, Marra CM, editors. Infections of the Central Nervous System. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott, Williams, & Wilkins; 2004. p. 537-68.

50. Hart RG, Foster JW, Luther MF, Kanter MC. Stroke in infective endocarditis. Stroke 1990;21:695-700.

51. Peters PJ, Harrison T, Lennox JL. A dangerous dilemma: Management of infectious intracranial aneurysms complicating endocarditis. Lancet Infect Dis 2006;6:742-8.

52. Bohmfalk GL, Story JL, Wissinger JP, Brown WE Jr. Bacterial intracranial aneurysm. J Neurosurg 1978;48:369-82.

|

|

|

|

| Dr. Ichiro Tonogai | Dr. Hiroki Arase | Dr. Yutaka Kawabata | Dr. Koichi Sairyo |

| How to Cite This Article: Tonogai I, Arase H, Kawabata Y, Sairyo K. Septic True Aneurysm of the Posterior Tibial Artery Diagnosed after Anterior Arthroscopic Debridement of a Septic Ankle following Infective Endocarditis: A Case Report. Journal of Orthopaedic Case Reports 2018 Nov-Dec; 8(6): 68-73. |

[Full Text HTML] [Full Text PDF] [XML]

[rate_this_page]

Dear Reader, We are very excited about New Features in JOCR. Please do let us know what you think by Clicking on the Sliding “Feedback Form” button on the <<< left of the page or sending a mail to us at editor.jocr@gmail.com