[box type=”bio”] Learning Point of the Article: [/box]

Brodie’s abscess should be considered in the setting of subacute osteomyelitis.

Case Report | Volume 10 | Issue 3 | JOCR May – June 2020 | Page 1-4 | Justin Chin, Tatsuhiko Naito, Kevin Hon, Christine Lomiguen. DOI: 10.13107/jocr.2020.v10.i03.1722

Authors: Justin Chin[1], Tatsuhiko Naito[2], Kevin Hon[3], Christine Lomiguen[4]

[1]Department of Family Medicine, Lifelong Medical Care,150 Harbour Way, Richmond, CA94801 USA,

[2]Department of Psychiatry, Putnam Hospital Center, 670 Stoneleigh Avenue, Carmel Hamlet, NY, 10512, USA,

[3]Department of Emergency Medicine, New York Presbyterian Hospital-Queens, 56-45 Main Street, Queens, NY, 11355, USA,

[4]Department of Pathology, Lake Erie College of Osteopathic Medicine, 1858 W Grandview Blvd, Erie, PA 16509 USA.

Address of Correspondence:

Dr. Justin Chin, DO,

Lifelong Medical Care, 150 Harbour Way, Richmond CA, 94801.

E-mail: justinchindo@gmail.com

Abstract

Introduction: Subacute osteomyelitis (OM) is a difficult condition to diagnose and treat, further complicated with an atypical presentation of a Brodie’s abscess (BA). BA is typically seen in pediatric, male populations, with minimal incidence in adult populations. Concern for malignancy and cold abscess can preempt oncological work-up. Duration of symptoms and radiological findings are often helpful but may not always match known classical findings.

Case Report: Here we present a case of subacute OM in a 30-year-old Japanese male with a distant medical history of OM as a child with a subsequent review of Brodie’s versus cold abscesses in the context of an atypical, asymptomatic presentation.

Conclusion: Clinical history and suspicion can be crucial to determine the presence of a BA in comparison to a cold abscess in the context of subacute OM. Crossing multiple disciplines from primary care and emergency treatment to orthopedic and oncological surgery, providers must be aware of atypical presentations of OM. Recurrence is unlikely with correct diagnosis and adequate surgical debridement and antibiotics, which, in turn, can improve patient outcomes and decrease unnecessary testing.

Keywords: Osteomyelitis, Brodie’s abscess, subacute, cold abscess, surgery.

Introduction

Osteomyelitis (OM) is an infection of bone traditionally classified by either the mechanism of bacterial introduction or duration of infection [1]. The overall incidence of OM in the United States or globally is largely unknown, with studies showing rates as high as 1 in 675 hospital admissions per year attributed to OM [2]. Common mechanisms for OM include hematogenous routes in the setting of bacteremia or spread from other sites versus non-hematogenous sources such as direct trauma and contiguous spread from bone [3]. Acute, subacute, and chronic OM are delineated and determined by the length and presentation of symptoms which can vary widely from localized erythema to ulcerative lesions [1, 3]. Staphylococcus aureus is the most common causative organism for OM; however, cultures can be negative in up to 50% of cases [1, 2]. Surgical biopsy and debridement are the gold standards for diagnosis and treatment, often requiring the placement of targeted local and oral antibiotics [4]. Here we present a case of subacute OM in a 30-year-old male with a distant medical history of OM as a child with a subsequent review of Brodie’s versus cold abscesses in the context of an atypical presentation.

Case Report

A 30-year-old Japanese male presented to the emergency room with a 4-month history of right leg discomfort, swelling, and intermittent serosanguinous drainage. The medical history was significant for OM of the right leg at age 4, requiring inpatient hospitalization in Japan for treatment with intravenous antibiotics and monitoring due to lesion proximity to the tibial growth plate. He reported no complications from the hospitalization, however, noted that the area of infection would have intermittent swelling and warmth.

During his pre-adolescent and adolescent years, the patient complained of “flare-ups,” in which he described mild pain with movement at the infection site, particularly during exercise and team sports. Episodes would occur as frequently as every 3 months, however, would self-resolve after several days with rest and over-the-counter nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications. Orthopedic evaluation and diagnostic imaging in Japan were largely inconclusive. Due to its benign, self-resolving course, the patient and his family elected for observation instead of further work-up.

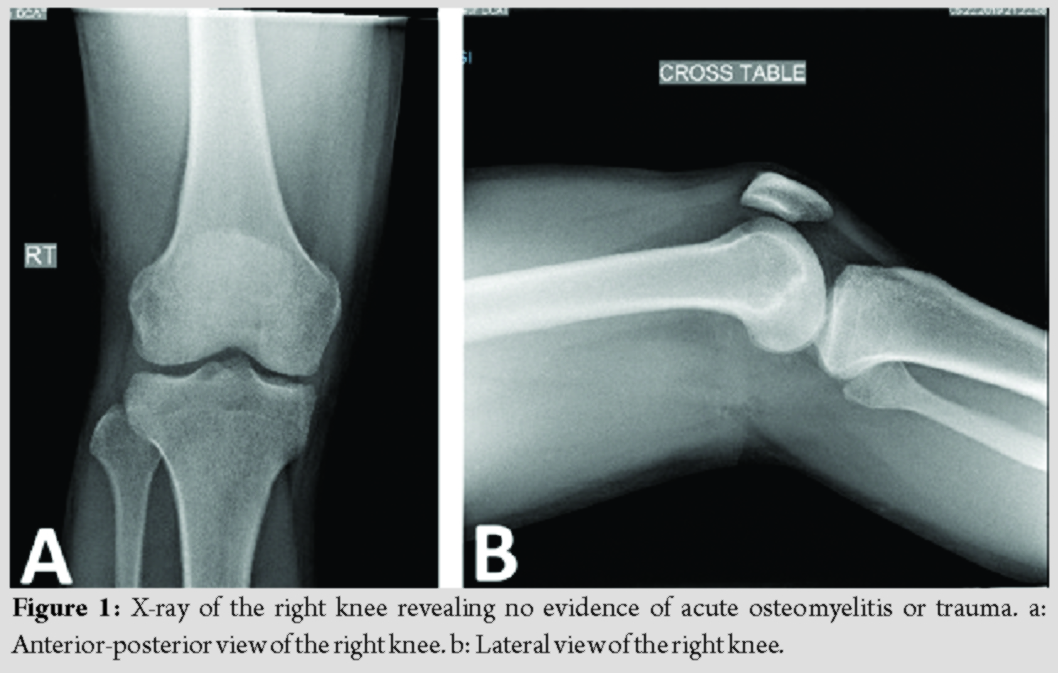

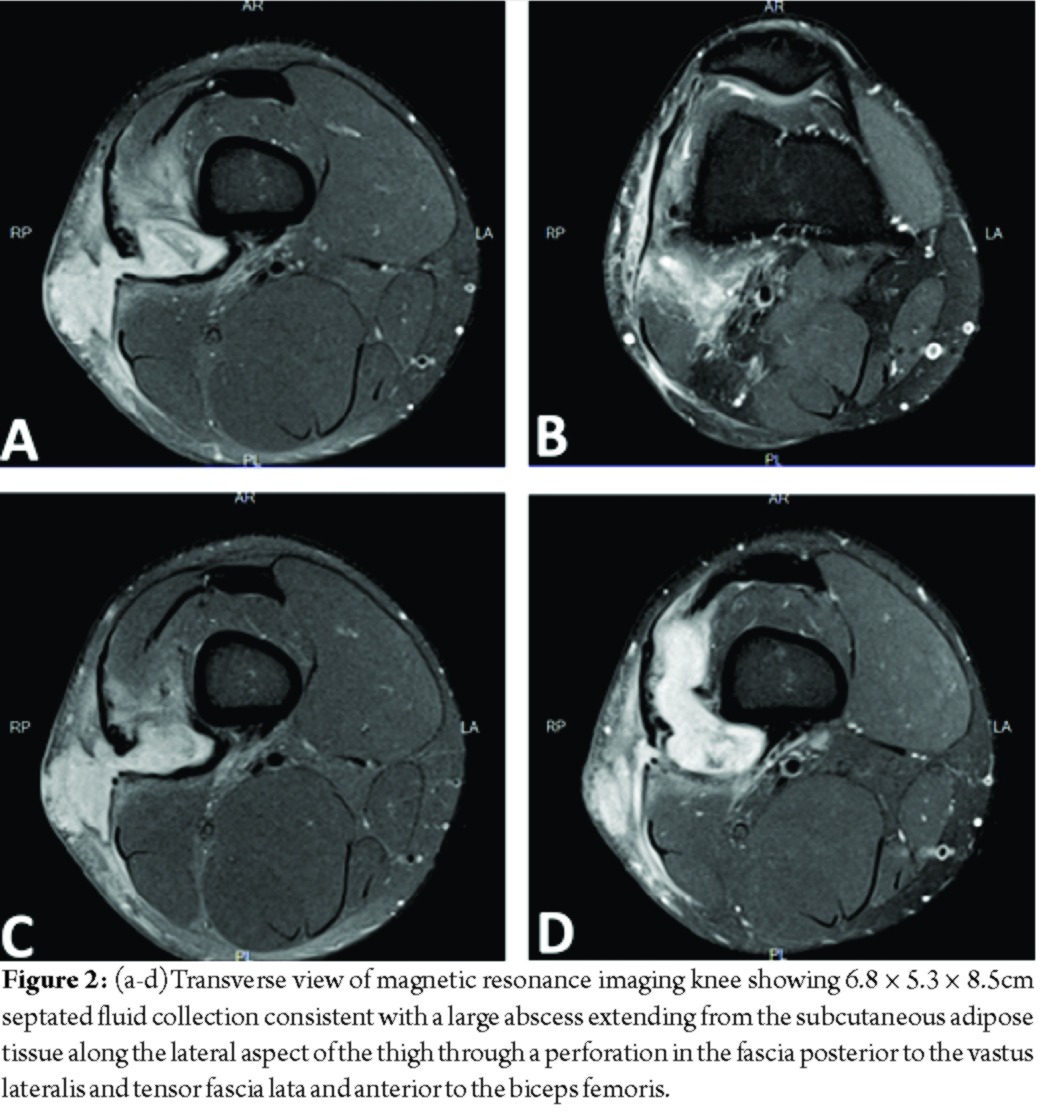

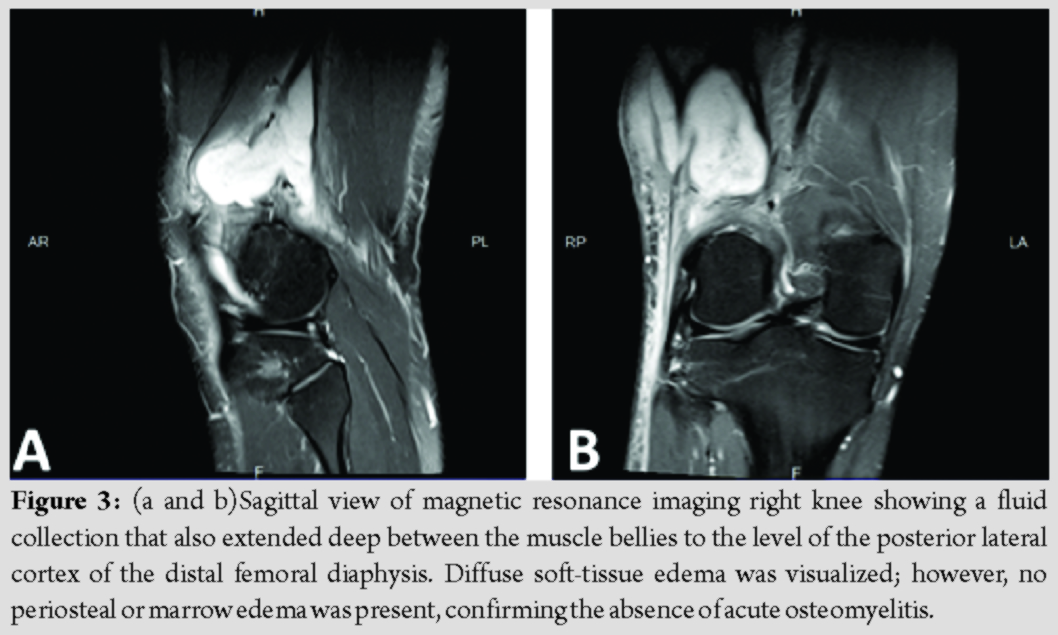

At presentation, the patient stated that this episode did not resolve with rest or anti-inflammatory medication. He reported the drainage had been ongoing for 2 weeks and appeared to come from a punctum in the center of the swelling, but denied any fever, chills, sharp pain, change in sensation, or restriction in active or passive range of motion. X-ray showed no acute OM or fractures (Fig. 1a and b). Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the knee revealed 6.8 × 5.3 × 8.5cm septated fluid collection consistent with a large abscess extending from the subcutaneous adipose tissue along the lateral aspect of the thigh through a perforation in the fascia posterior to the vastus lateralis and tensor fascia lata and anterior to the biceps femoris (Fig. 2a-d). The fluid collection also extended deep between the muscle bellies to the level of the posterior lateral cortex of the distal femoral diaphysis. Diffuse soft-tissue edema was visualized; however, no periosteal or marrow edema was present, confirming the absence of acute OM (Fig. 3a and b).

Surgical and orthopedic consultation determined that no acute intervention was required at the time and for the patient to follow-up as an outpatient. Subsequent culture and biopsy revealed granulation tissue with skin flora. Concern for possible cold abscess versus malignancy resulted in transfer of care to orthopedic oncology, who recommended open debridement to better evaluate and treat the abscess. On opening the site, copious scar tissue and cystic debris were evacuated from the area, with gross appearance consistent with longstanding subacute OM and a Brodie’s abscess (BA). Bone biopsy and culture revealed methicillin-sensitive S. aureus. Polymethylmethacrylate antibiotic beads were placed and the incision closed in a standard fashion. Infectious disease recommended that the patient be discharged on 6 weeks of Keflex (Cephalexin). At the 6-month follow-up, the patient reported return to his baseline mobility after physical therapy and no flare-ups of his previous symptoms.

Discussion

Subacute OM is a long-standing low-grade infection of the bone that is often asymptomatic for long periods of time[5]. Onset is frequentlyinsidious and lacking an inciting factor or insult; the first symptoms at presentation can be erythematous swelling, tenderness over the area, and frank pain [6]. Various studies have hypothesized that the development of subacute OM can be multifactorial, which can include inadequate treatment of acute OM, prior antibiotic exposure and resistance, or some combination of the aforementioned [5, 6]. Laboratory evaluation is typically benign as seen in the case presented, with a normal white blood cell count and differential, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and other markers of infection [7]. Due to its clinically silent nature, diagnosis and treatment are often delayed resulting in sequelae ranging from abscess formation to incomplete debridement leading to reoccurrence [2, 7]. Similar to this case, the patient and familial expectations and knowledge regarding OM can also dictate whether treatment occurs [8]. With its labile nature that waxed and waned throughout the years, the case patient developed compensatory mechanisms due to the frequent self-resolution of symptoms. BA is a suppurative collection of necrosis that is encapsulated by granulation tissue in the setting of subacute or chronic OM [9]. First described in the 1830s, BA is commonly found in the proximal and distal metaphyseal region of long bones, particularly the tibia; however, case reports have described its presence in many skeletal locations [9, 10]. Similar to subacute OM, onset is often insidious as pain can be intermittent and may lack the fever or other systemic side effects expected with abscess formation [11]. More commonly found in male pediatric populations, surgical exploration and direct visualization are required as radiological work-up typically cannot exclude osteoid osteoma [12]. Rarely, BA can progress to a draining abscess to the skin as a result of abscess perforation or breakdown, which may have been present with the case patient [13]. A penumbra sign of a rim-lined abscess cavity with high signal intensity on T1-weighted images is a defining feature of BA; this was absent in the patient’s MRI work-up [14]. Similar to OM, BA cultures frequently grow Staphylococcus aureus, requiring antibiotics at discharge [9]. With our case patient, the duration of symptoms and inconclusive radiology complicated definitive diagnose of BA in addition to subacute OM. Similar to a BA, a cold abscess is also a collection of necrosis that is encapsulated by granulation tissue and lacks the localized pain and systemic symptoms associated with infection and inflammation [15]. Latent tuberculosis and fungal blastomycosis have been the most reported causes of cold abscess and are also associated with patients that have hyperimmunoglobulin E syndrome [16, 17, 18]. Most cases manifest in the chest and thoracic region due to presumptive proximity to tuberculosis infection of the lungs or, rarely, disseminated miliary tuberculosis [19]. Cold abscess formation has also been observed in relation to improper administration or adverse reaction formation to improper administration or adverse side effects in relation to pediatric intramuscular vaccination to the thigh [20]. For the case patient, he was given the Bacillus Calmette–Guerin vaccine as a child but had documented negative testing with blood interferon-gamma release assays. Due to low-risk factors associated with cold abscesses, the patient was correctly worked up for subacute OM and BA. Of note, there are no cases that document subacute OM resulting in a cold abscess or vice versa.

Conclusion

Subacute OM is a difficult condition to diagnose and treat, further complicated with an atypical presentation of a BA. Duration of symptoms and MRI findings are often helpful but may not always match known classical findings. As seen in the case, clinical history and suspicion can be crucial to determine the presence of a BA in comparison to a cold abscess. Recurrence is unlikely with correct diagnosis and adequate surgical debridement and antibiotics, which, in turn, can improve patient outcomes and decrease unnecessary testing.

Clinical Message

Subacute osteomyelitis is a difficult condition to diagnose and treat, further complicated with an atypical presentation of a Brodie’s abscess. Brodie’s abscess is typically seen in pediatric, male populations, with minimal incidence in adult populations. Concerns for malignancy and cold abscess can preempt oncological work-up. Duration of symptoms and radiological findings are often helpful but may not always match known classical findings. Crossing multiple disciplines from primary care and emergency treatment to orthopedic and oncological surgery, providers must be aware of atypical presentations of osteomyelitis.

References

1. Schmitt SK. Osteomyelitis. Infect Dis Clin North Am 2017;31:325-38.

2. Kremers HM, Nwojo ME, Ransom JE, Wood-Wentz CM, Melton LJ 3rd, Huddleston PM 3rd. Trends in the epidemiology of osteomyelitis: A population-based study, 1969 to 2009. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2015;97:837-45.

3. Waldvogel FA, Medoff G, Swartz MN. Osteomyelitis: A review of clinical features, therapeutic considerations and unusual aspects. N Engl J Med 1970;282:198-206.

4. Hatzenbuehler J, Pulling TJ. Diagnosis and management of osteomyelitis. Am Fam Physician 2011;84:1027-33.

5. Hayes CS, Heinrich SD, Craver R, MacEwen GD. Subacute osteomyelitis. Orthopedics 1990;13:363-6.

6. Mandell JC, Khurana B, Smith JT, Czuczman GJ, Ghazikhanian V, Smith SE. Osteomyelitis of the lower extremity: Pathophysiology, imaging, and classification, with an emphasis on diabetic foot infection. Emerg Radiol 2018;25:175-88.

7. Shih HN, Shih LY, Wong YC. Diagnosis and treatment of subacute osteomyelitis. J Trauma 2005;58:83-7.

8. Dartnell J, Ramachandran M, Katchburian M. Haematogenous acute and subacute paediatric osteomyelitis: A systematic review of the literature. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2012;94:584-95.

9. Van Der Naald N, Smeeing DP, Houwert RM, Hietbrink F, Govaert GA, Van Der Velde D. Brodie’s abscess: A systematic review of reported cases. J Bone Jt Infect 2019;4:33-9.

10. Brodie BC. An account of some cases of chronic abscess of the tibia. Med Chir Trans 1832;17:239-49.

11. McHugh CH, Shapeero LG, Folio L, Murphey MD. Case for diagnosis. Brodie abscess. Mil Med 2007;172:8-11.

12. Schlur C, Bachy M, Wajfisz A, Ducou le Pointe H, Josset P, Vialle R. Osteoid osteoma mimicking Brodie’s abscess in a 13-year-old girl. Pediatr Int 2013;55:e29-31.

13. Hammad A, Leute PJ, Hoffmann I, Hoppe S, Lakemeier S, Klinger HM. Acute leg pain with suspected beginning leg compartment syndrome and deep vein thrombosis as differential diagnoses in an unusual presentation of Brodie’s abscess: A case report. J Med Case Rep 2015;9:292.

14. Afshar A, Mohammadi A. The “Penumbra Sign” on magnetic resonance images of Brodie’s abscess: A case report. Iran J Radiol 2011;8:245-8.

15. Ben Saad S, Kallel N, Gharsalli H, Kwas H, El Gharbi L, Ghedira H, et al. Cold abscess in the immunocompetent subject. Tunis Med 2018;96:302-6.

16. Castillo CG, Kauffman CA, Miceli MH. Blastomycosis. Infect Dis Clin North Am 2016;30:247-64.

17. Garg RK, Somvanshi DS. Spinal tuberculosis: A review. J Spinal Cord Med 2011;34:440-54.

18. Holland SM, DeLeo FR, Elloumi HZ, Hsu AP, Uzel G, Brodsky N, et al. STAT3 mutations in the hyper-IgE syndrome. N Engl J Med 2007;357:1608-19.

19. Moyano-Bueno D, Blanco JF, Lopez-Bernus A, Gutierrez-Zubiaurre N, Gomez Ruiz V, Velasco-Tirado V, et al. Cold abscess of the chest wall: A diagnostic challenge. Int J Infect Dis 2019;85:108-10.

20. Al Namshan M, Oda O, Almaary J, Al Jadaan S, Crankson S, Al Banyan E, et al. Bacillus Calmette-Guerin-related cold thigh abscess as an unusual cause of thigh swelling in infants following BCG vaccine administration: A case series. J Med Case Rep 2011;5:472.

|

|

|

|

| Dr. Justin Chin | Dr. Tatsuhiko Naito | Dr. Kevin Hon | Dr. Christine Lomiguen |

| How to Cite This Article: Chin J, Naito T, Hon K, Lomiguen C. Challenges in the Diagnosis of Brodie’s Abscess in Subacute Osteomyelitis. Journal of Orthopaedic Case Reports 2020 May-June;10(3): 1-4. |

[Full Text HTML] [Full Text PDF] [XML]

[rate_this_page]

Dear Reader, We are very excited about New Features in JOCR. Please do let us know what you think by Clicking on the Sliding “Feedback Form” button on the <<< left of the page or sending a mail to us at editor.jocr@gmail.com