[box type=”bio”] Learning Point of the Article: [/box]

Reconstruction with proximal radius allograft is a solution to treat giant cell tumor of the proximal radius..

Case Report | Volume 10 | Issue 3 | JOCR May – June 2020 | Page 32-35 | Marco Bernardes, Filipe Santos, Miguel Frias, David Sá, Guido Duarte, Rui Lemos. DOI: 10.13107/jocr.2020.v10.i03.1736

Authors: Marco Bernardes[1], Filipe Santos[1], Miguel Frias[1], David Sá[1], Guido Duarte[1], Rui Lemos[1]

[1]Department of Orthopaedics and Traumatology, Centro Hospitalar de Vila Nova de Gaia/Espinho, Gaia, Portugal.

Address of Correspondence:

Dr. Marco Bernardes,

Department of Orthopaedics and Traumatology, Centro Hospitalar de Vila Nova de Gaia/Espinho, Gaia, Portugal.

E-mail: marquitobernardes@hotmail.com

Abstract

Introduction: Giant cell tumor (GCT) of bone is a locally aggressive benign neoplasm that accounts for 4–10% of all primary bone tumors. It affects mostly young adults and occurs more frequently at the bones around the knee followed by the distal radius and the sacrum. Surgical treatment with curettage is the optimal treatment for local tumor control, but it can be associated to suboptimal functional outcome when located in periarticular regions.

Case Report: We describe a 47-year-old Caucasian female who presented with pain in the proximal third of the left forearm without history of traumatism. The study performed revealed a pathological fracture of the proximal radius associated with lytic lesion. The patient underwent excision and curettage of the lesion with preservation of the periosteum, filling with the left proximal radius (corpse) allograft and osteosynthesis with plate and screws. The anatomopathological examination revealed characteristics compatible with GCT.

Conclusion: This case presents some unique features: The extremely rare location of the GCT at the proximal end of the radius, its initial presentation as a pathological fracture, and the type of treatment performed (reconstruction with the left proximal radius allograft-corpse), with good results.

Keywords: Giant cell tumor of bone, reconstructive surgery, allograft.

Introduction

The giant cell tumor (GCT) accounts for about 4–10% of primary bone neoplasms [1]. It appears, in most cases, as a benign tumor but is often a local aggressive lesion. However, it can have a wide spectrum of presentations, ranging from latent benign to highly recurrent and occasionally metastatic malignant potential [2]. They typically occur between the second and fourth decade of life, with a slight predominance in females [3]. Pain is the most common symptom and is rarely severe, except when an associated pathological fracture occurs. In 10–12% of patients, pathological fractures are evident at the initial diagnosis [1, 3, 4, 5].

Case Report

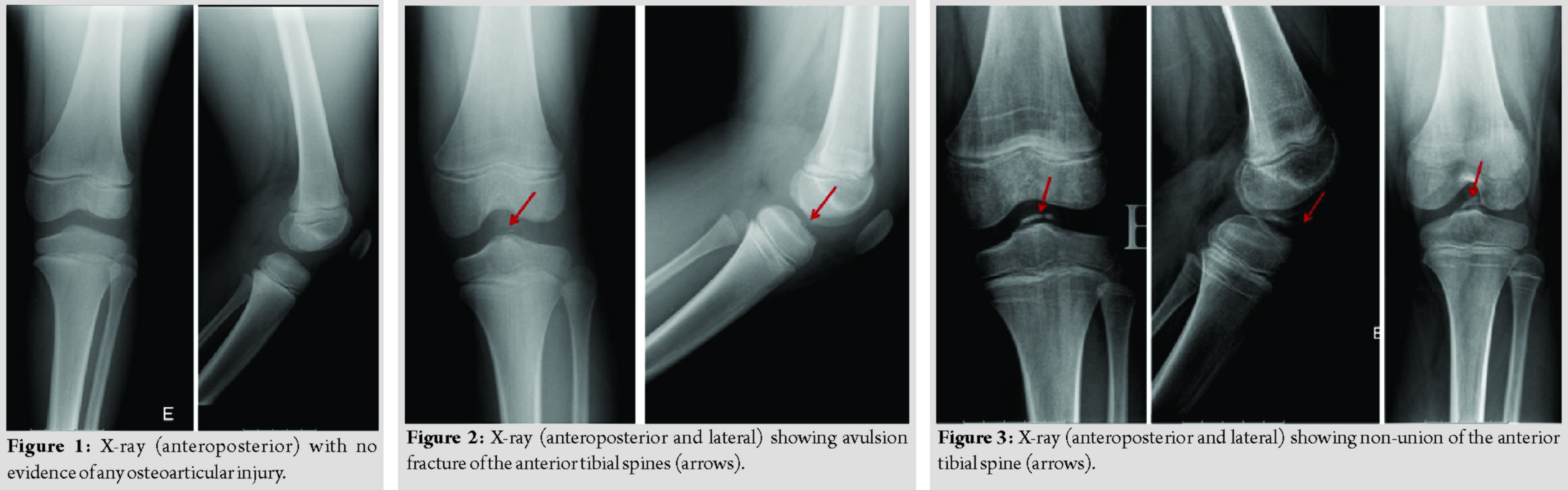

A 47-year-old Caucasian female, trader, with no relevant medical history, presented to the emergency department for pain in the proximal third of the left forearm, of sudden onset, intense, after movement of pronation, without a history of traumatism. She had no fever, no inflammatory signs, but she had pain on the palpation of the proximal radius and limitation of the active and passive mobilities. The radiographs of the elbow and forearm showed a pathological fracture of the proximal radius associated with lytic lesion (Fig. 1). Computed tomography (CT) scan of the left elbow showed “lytic lesion, with 57 × 18 mm, reduction and fragmentation of cortical thickness –a pathological fracture; without suspected reaction of the periosteum” (Fig. 2).

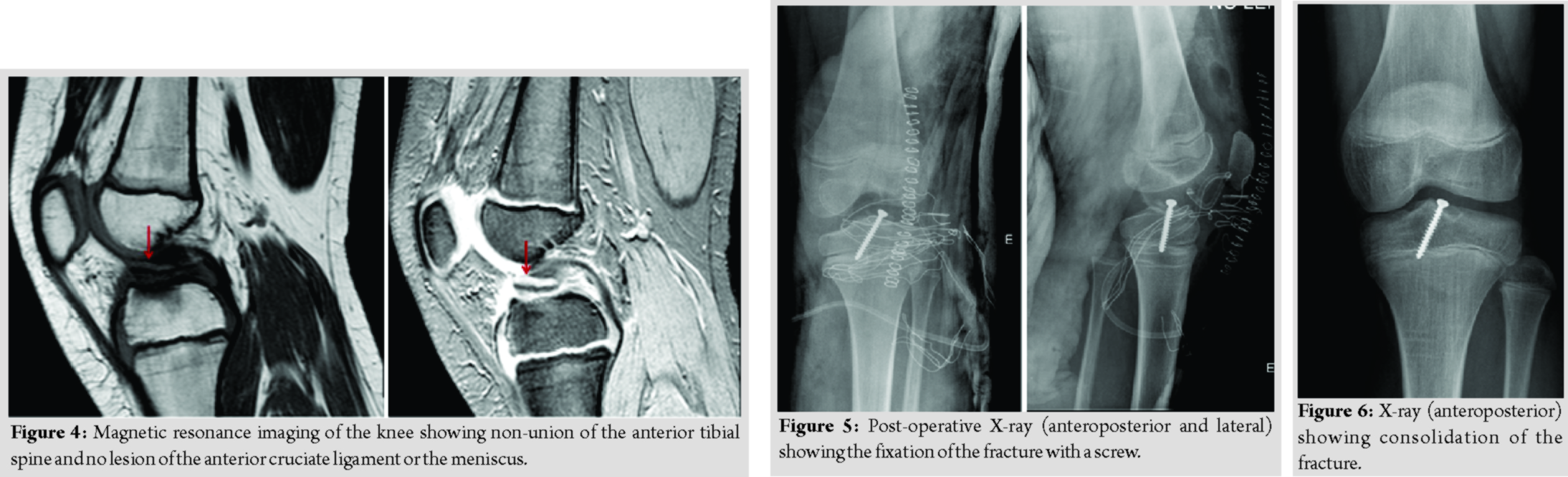

An immobilization of the left arm and forearm was performed. The magnetic resonance imaging of the left forearm revealed “primary bone lesion without invasive features of the soft tissues that can correspond to aneurysmal bone cyst or GCT” (Fig. 3). A biopsy and surgery were proposed. The patient underwent excision and curettage of the lesion with preservation of the periosteum, filling with the left proximal (corpse) allograft and osteosynthesis with plate and screws (Fig. 4).

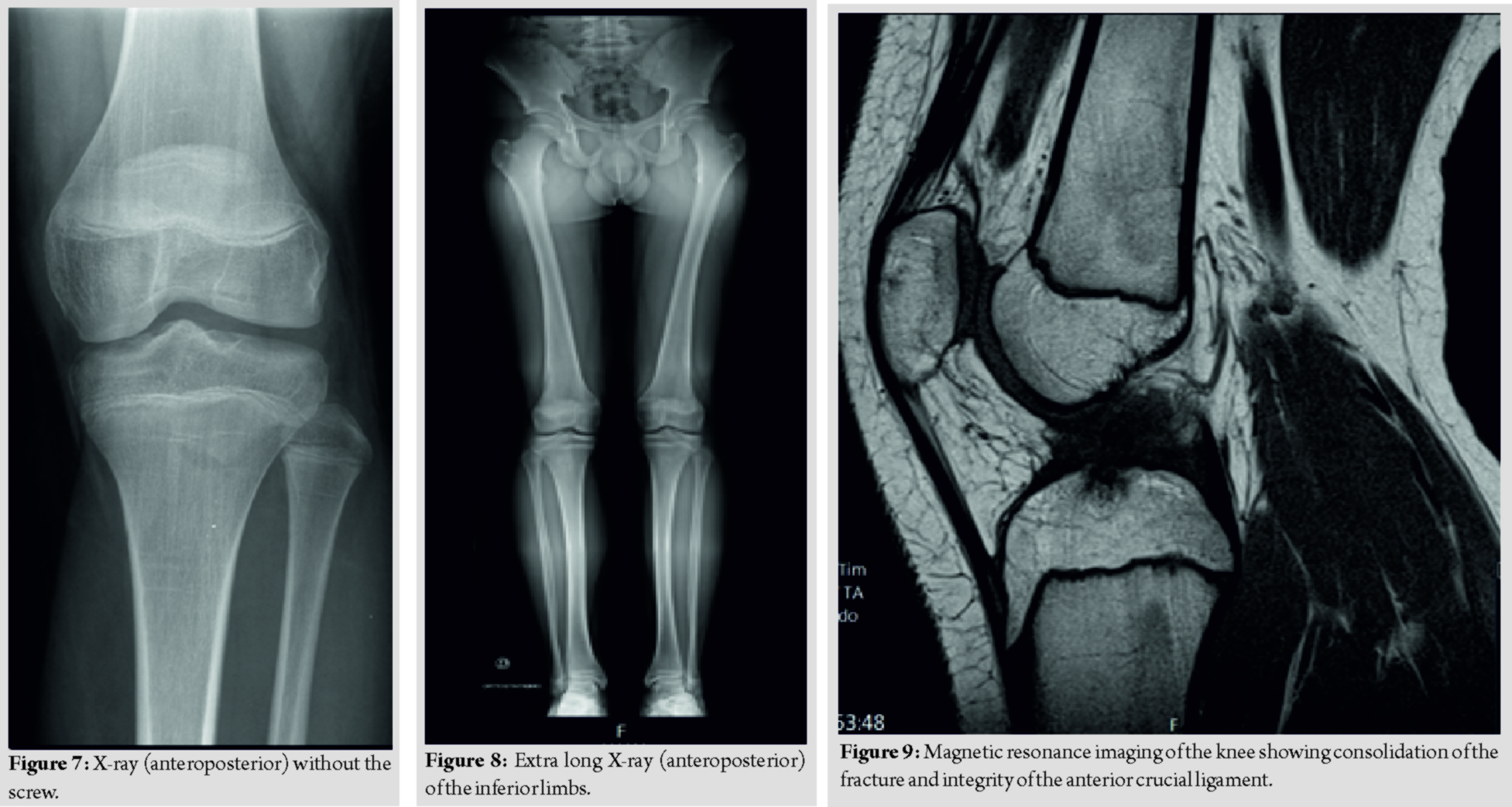

The anatomopathological examination revealed characteristics compatible with GCT of bone (Fig. 5). The surgery was uneventful and there was no neurovascular injury. The post-operative period was also uneventful. During follow-up, a good clinical and radiological evolution was observed, with consolidation of the lesion (Fig. 6) and recovery of the arch of mobility of the elbow, presenting a deficit of 15° of supination compared to the contralateral side. There was no local recurrence of the lesion and there was no metastization in 2 years of follow-up.

Discussion

This case report is important for many reasons; at first, it evidences a very rare location of the GCT in the proximal end of the radius. Second, its initial presentation as a pathological fracture is also very rare. At last, the type of treatment performed in this case is innovative as long as in the literature, there is not any case describing the reconstruction of proximal radius with a corpse proximal radius (allograft) with good clinical and imagiologic results. The most common location of this type of tumor is the distal femur followed by the proximal tibia; the distal radius and sacrum are also often involved [3, 4, 5]. It is rarely located at the proximal end of the radius with only few cases reported in the literature [6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12]. Surgical treatment is the treatment of choice for GCT. The tumor can be removed either by resection or with curettage, depending on the involvement of the articular surfaces. Resection with wide margins has been associated with few or no recurrences but less favorable functional outcome. For the other hand, curettage presents higher recurrence rates but less morbidity and functional impairment for the patients [1, 13]. Besides, the recurrence of the tumor can be reduced when curettage is combined both with local adjuvants and/or systemic agents. The first includes cementation with polymethyl methacrylate, alcohol, phenol, hydrogen peroxide, zinc chloride, cryoablation with liquid nitrogen, speed burr drilling, and local application of zoledronic acid [13, 14]. The systemic agents used are denosumab, bisphosphonates, and interferon-alpha [14]. In this case, taking into account, the characteristics of the lesion, namely, its size and location in relation with the elbow, the authors chose to perform curettage with graft (allograft) placement and its rigid fixation with plate and screws. This treatment is different from the ones described in the cases reported in the literature. In some of the cases reported, resection without reconstruction was the only treatment performed [7, 9, 10, 11]. In other cases, resection was associated to different type of reconstructions with autologous graft [8, 12]. In one of these cases, the reconstruction of the proximal radius was made with free fibula which seems to offer good results and must be taken into account when performing this kind of reconstruction [12]. However, the morbidity and possible complications associated with the “Donner place” are not negligible. At last, one case describes the use of reconstruction with bank bone graft not stating the characteristics of the graft (location, size, etc.) [6]. In our case, we used an allograft of a proximal radius with nearly the same size and shape of the patient’s radius resected with good functional and radiologic outcomes and no evidence of recurrence in 2 years of follow-up. The authors believe that the use of this kind of allograft brings good functional results and avoids additional patient’s morbidity related to autografts. The other features that the authors want to highlight arethe extremely rare presentation of these lesions as pathologic fracture that happened in this case and in only two cases related in the literature [6, 7, 8, 9, 10].

Conclusion

GCT of bone, although mostly benign, can have alocal aggressive behavior leading to the need of local aggressive surgeries that can imply the loss of functional performance, especially when located in periarticular regions. Hence, when possible, reconstructive surgeries, as the one made in this case, should be tried in these patients who are mainly young. The authors want to highlight the peculiarities of this case by the extremely rare location of the GCT at the proximal end of the radius, its initial presentation as a pathological fracture, and the type of treatment performed (reconstructive with allograft), with very good results.

Clinical Message

With this paper, the authors pretend to present a case with some unique features: The extremely rare location of the GCT at the proximal end of the radius, its initial presentation as a pathological fracture, and the type of treatment performed (reconstruction with left proximal radius allograft – corpse), with good results.

References

1. Turcotte RE. Giant cell tumor of bone. Orthop Clin North Am 2006;37;35-51.

2. Dorfman HD, Czerniak B. Bone Tumors. St. Louis: Mosby; 1998.

3. Kransdorf M, Murphey M. Giant cell tumor. In: Davies M, Sundaram M, James S, Editors. The Imaging of Bone Tumors and Tumor-Like Lesions. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag; 2009.

4. Dahlin DC, Cupps RE, Johnson EW Jr. Giant-cell tumor: A study of 195 cases. Cancer 1970;25:1061-70.

5. Unni KK, Dahlin DC. Dahlin’s Bone Tumors: General Aspects and Data on 11,087 Cases. 5th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott-Raven; 1996.

6. Lewis MM, Kaplan H, Klein MJ, Ferriter PJ, Legouri RA. Giant cell tumor of the proximal radius. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1985;201:186-9.

7. Mir NA, Bhat JA, Halwai MA. Giant cell tumours of proximal radius and patella-an unusual site of presentation. JK Sci 2003;5:35-7.

8. Akmaz I, Arpacioglu MO, Pehlivan O, Solakoglu C, Mahirogullari M, Kiral A, et al. An infrequent localization of giant cell tumour: Proximal radius: Case report. J Arthroplast Arthroscop Surg 2004;15:174-7.

9. Singh AP, Mahajan S, Singh AP. Giant cell tumour of the proximal radius. Singap Med J 2009;50:388-90.

10. Song WS, Cho WH, Kong CB, Jeon DG. Composite reconstruction after proximal radial giant cell tumor resection. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2011;131:627-30.

11. Khan KM, Minhas MS, Khan MA, Bhatti A. Giant cell tumour of proximal radius in a 48 years old lady. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak 2014;24 Suppl 1:S48-9.

12. Dahuja A, Kaur R, Bhatty S, Garg S, Bansal K, Singh M. Giant-cell tumour of proximal radius in a 50-year-old female with wrist drop: A rare case report. Strategies Trauma Limb Reconstr 2017;12:193-6.

13. Zhen W, Yaotian H, Songjian L, Ge L, Qingliang W. Giant-cell tumour of bone. The long-term results of treatment by curettage and bone graft. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2004;86:212-6.

14. Mavrogenis AF, Igoumenou VG, Megaloikonomos PD, Panagopoulos GN, Papagelopoulos PJ, Soucacos PN. Giant cell tumor of bone revisited. SICOT J 2017;3:54.

|

|

|

|

|

| Dr. Marco Bernardes | Dr. Miguel Frias | Dr. David Sá | Dr. Guido Duarte | Dr. Rui Lemos |

| How to Cite This Article: Bernardes M, Santos F, Frias M, Sá D, Duarte G, Lemos R. Giant Cell Tumor with Fracture of the Proximal Radius – Reconstructive Surgery with Radius Allograft. Journal of Orthopaedic Case Reports 2020 May-June;10(3): 32-35. |

[Full Text HTML] [Full Text PDF] [XML]

[rate_this_page]

Dear Reader, We are very excited about New Features in JOCR. Please do let us know what you think by Clicking on the Sliding “Feedback Form” button on the <<< left of the page or sending a mail to us at editor.jocr@gmail.com