[box type=”bio”] Learning Point of the Article: [/box]

Acute posterior shoulder dislocation requires early diagnosis (clinical exam and anteroposterior and Bloom-Obata views) and reduction under general anesthesia for a post-reduction testing.

Case Report | Volume 10 | Issue 3 | JOCR May – June 2020 | Page 43-46 | R. Dukan, Y. Ouchrif, C. Glorion. DOI: 10.13107/jocr.2020.v10.i03.1740

Authors: R. Dukan[1], Y. Ouchrif[1], C. Glorion[1]

[1]Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, Necker-Enfants Malades University Hospital, 149 Rue de Sèvres, 75015 Paris, France.

Address of Correspondence:

Dr. R. Dukan,

Department Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery, Necker-Enfants Malades University Hospital, 149 Rue de Sèvres, 75015 Paris, France.

E-mail: ruben.dukan@gmail.com

Abstract

Introduction: Traumatic posterior dislocation of the shoulder is exceedingly rare in pediatric patients. Main causes are obstetrical brachial plexus injury; congenital abnormalities of the glenohumeral joint; and voluntary dislocation, which are often multidirectional. Treatment is not consusual and depends on early diagnosis.

Case Report: Posterior shoulder dislocation was diagnosed in a 9-year-old boy while practicing judo. His right upper limb was held adducted and internally rotated and could not be externally rotated. Bloom-Obata axial view and computed tomography-scan allowed us to make the diagnosis. Reduction was performed under general anesthesia. No injuries were detected on post-reduction magnetic resonance imaging. At 18 months patient had recovered all his shoulder mobility.

Conclusion: Traumatic posterior shoulder dislocation is exceedingly rare in pediatric patients. Treatment is easy and effective at the acute phase. Awareness of the presentation of posterior shoulder dislocation is crucial to allow the early diagnosis and treatment.

Keywords: Posterior dislocation, shoulder, child, martial art.

Introduction

Traumatic posterior dislocation of the shoulder is exceedingly rare in pediatric patients, and only very few cases have been published [1, 2, 3, 4]. Ligaments are stronger than the proximal humeral physis, and epiphyseal separation is consequently more likely to occur than glenohumeral dislocation [5]. We managed a 9-year-old boy with posterior shoulder dislocation after he was thrown while practicing judo. The objective of this case-report is to describe the specific features of posterior shoulder dislocation in pediatric patients, to emphasize the importance of an early diagnosis, and to discuss the available treatment options. Informed consent was required from the patient and his parents for the publication of this case.

Case Report

A 9-year-old boy presented with pain and a complete inability to use his right arm after being thrown while practicing judo. His right upper limb was held adducted and internally rotated. External rotation was limited. Acromion and coracoid process were prominent anteriorly. Humeral head was palpable posteriorly with a flattened anterior shoulder (Fig. 1). There was no evidence of vascular or nerve injury, particularly the axillary nerve.

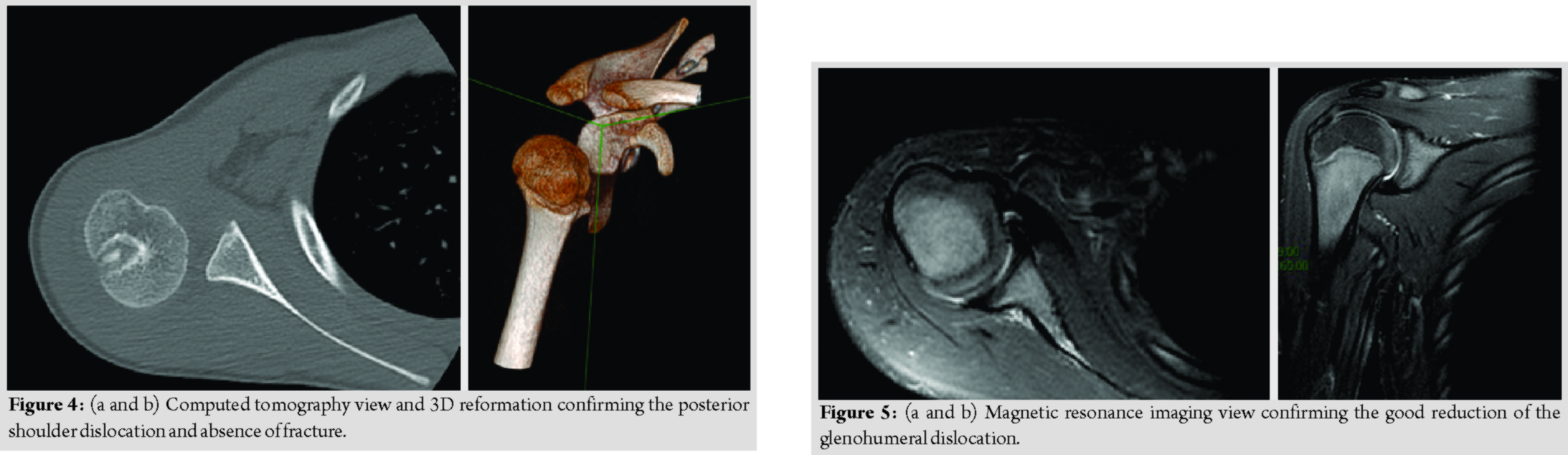

The anteroposterior radiograph of the shoulder seemed normal (Fig. 2). However, several radiological signs were in favor of the diagnosis: The lightbulb sign (head of the humerus was in the same axis as the shaft) and the rim sign (widening of the glenohumeral space >6mm). The Bloom-Obata modified axial view showed a humeral head that was displaced behind the glenoid cavity (Fig. 3). Shoulder computed tomography (CT)-scan confirmed the posterior shoulder dislocation and the absence of scapular or proximal humeral fracture (Fig. 4).

Closed reduction was performed in the operating room under general anesthesia. The main operator performed an axial traction with exaggerating internal rotation and assistant applied continuous pressure to the posterior part of the humeral head to obtain the reduction. Shoulder reduction was controlled under fluoroscopic control. Shoulder was stable during stress testing. Immobilization was ensured for 4 weeks by a thoracobrachial cast holding the right arm in 20° of abduction and neutral rotation. To limit radiation exposure, magnetic resonance imaging was used to confirm that the glenohumeral joint was properly reduced. There was no injury of the soft-tissue structures (posterior capsule, tendon of long head of biceps, rotator cuff, and deltoid) (Fig. 5).

After 4 weeks, cast was removed and patient was encouraged to swim as a self-rehabilitation method. He recovered full range of motion 3 weeks after cast removal (Fig. 6) and returned to judo after 5 months. At last follow-up, 18 months after the injury, he had no recurrences.

Discussion

Posterior shoulder dislocation is a rare injury that accounts for only 1–4.7% of all shoulder dislocations in adults [6]. In pediatric patients, the main causes are obstetrical brachial plexus injury; congenital abnormalities of the glenohumeral joint; and voluntary dislocation, which are often multidirectional [5, 6]. Trauma is an exceedingly rare cause in children. The first reported case of traumatic posterior shoulder dislocation in a child was published in 1985 [6]. The two main mechanisms of traumatic posterior shoulder dislocation are a direct impact on the anterior shoulder that propels the humeral head posteriorly, and indirect forced flexion-adduction-internal rotation of the shoulder. Seizures due to epilepsy or electrocution are a well-known cause of posterior shoulder dislocation, particularly in adults [1, 2, 6]. Dislocation occurs during the tonic phase of the seizure due to a contraction imbalance in the internal and external rotator muscles. Establishing the diagnosis is crucial. Posterior shoulder dislocation is easily missed at the acute phase. Patients are then diagnosed only at the chronic phase, which are difficult to treat and associated with poor outcomes [2]. Pain is a constant symptom. The most common physical findings are prominence of the coracoid process anteriorly and humeral head posteriorly and, most importantly, a complete inability to rotate the humerus externally. Patients must be assessed for injuries to blood vessels and nerves, notably the axillary nerve. Radiographs should be obtained to confirm the diagnosis and to search fractures [2, 5, 6]. The anteroposterior view may be normal but several radiological signs such as the lightbulb sign (head of the humerus was in the same axis as the shaft) and the rim sign (widening of the glenohumeral space >6mm) must alert the surgeon about the existence of a posterior dislocation. However, the shoulder should be assessed on lateral views such as the axillary view, glenoid profile view, and Bloom-Obata modified axial view [7]. CT-scan is useful to detect fractures of the glenoid and tuberosities or notches in the humeral head. Wagner and Lyne reported that proximal humeral epiphyseal separation was the most common bone injury in adolescents with shoulder dislocation [8]. Nakae and Endo [3] described a case of traumatic posterior shoulder dislocation with a fracture of the acromion in a 14-year-old boy. Acute shoulder dislocation requires reduction under general anesthesia. Reduction maneuver involves applying light traction to the adducted arm while gently pushing the humeral head forwards. Stability in internal rotation must be tested carefully after reduction. The systematic immobilization of these dislocations by a thoracobrachial cast will be performed by specialists who are experienced in this type of immobilization. Wilson and McKeever stated that most of the posterior shoulder dislocations were unstable and preferred temporary stabilization by two percutaneous acromio-humeral K-wires [4]. Recommended duration of immobilization ranges from 2 to 4 weeks. Open reduction is indicated when external maneuvers fail due to incarceration of bony fragments or of the tendon of long head of biceps. Chronic dislocation is a major therapeutic challenge. Surgical reduction is usually required. The prognosis is reserved, with high risk of major complications such as residual shoulder stiffness, soft-tissue injury during the surgical approach, and avascular necrosis of the humeral head [2, 9]. Epiphyseal separation, if present, requires accurate reduction followed by K-wire stabilization to minimize the risk of epiphysiodesis and avascular necrosis of the humeral head [9]. No cases of posterior shoulder instability after traumatic dislocation have been reported in children, perhaps due to the short follow-ups [1, 2, 6]. There were no recurrences in our patient during the 18-month follow-up. The management of chronic posterior shoulder instability in children involves rehabilitation therapy for at least 6–12 months followed, if rehabilitation fails, by surgery to stabilize the shoulder. Stabilizing procedures include soft-tissue techniques such as posterior Bankart repair, posterior capsulorrhaphy, posterior transfer of the long head of the biceps tendon, and capsular plication. Techniques involving the bone consist of the posterior bone block procedure, glenoid osteotomy, and humeral osteotomy. The best outcomes have been obtained by combining a soft-tissue procedure with a bony procedure [10].

Conclusion

Traumatic posterior shoulder dislocation is exceedingly rare in pediatric patients. A careful physical examination and appropriate radiographic views ensure the diagnosis. Treatment is easy and effective at the acute phase. In neglected cases, in contrast, prognosis is reserved. Awareness of the presentation of posterior shoulder dislocation is therefore crucial to allow the early diagnosis and treatment.

Clinical Message

Posterior shoulder dislocation is a rare injury. Establishing an early diagnosis is crucial. Clinical exam is difficult. Anteroposterior view may be normal but several radiological signs such as the lightbulb sign and the rim sign must alert the surgeon. Bloom-Obataview can be useful. In any doubt, CT-scan confirms the diagnosis. Acute shoulder dislocation requires reduction under general anesthesia for a post-reduction testing. Immobilization is needed after.

References

1. Cziffer E, Habel T, Kepes P. Posterior shoulder dislocation: Pitfalls and perils. Orthopedics 1993;16:97-9.

2. Kumar Y, Verma A, Maini L, Gautam V. Traumatic neglected posterior dislocation of shoulder in a child-a rare entity. J Clin Orthop Trauma 2011;2:117-8.

3. Nakae H, Endo S. Traumatic posterior dislocation of the shoulder with fracture of the acromion in a child. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 1996;115:238-9.

4. Wilson JC, McKeever FM. Traumatic posterior dislocation of the humerus. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1949;31:160-72.

5. May VR. Posterior dislocation of the shoulder: Habitual, traumatic, and obstetrical. Orthop Clin North Am 1980;11:271-85.

6. Foster WS, Ford TB, Drez D. Isolated posterior shoulder dislocation in a child. A case report. Am J Sports Med 1985;13:198-200.

7. Pollock RG, Bigliani LU. Recurrent posterior shoulder instability. Diagnosis and treatment. Clin Orthop 1993;291:85-96.

8. Wagner KT, Lyne ED. Adolescent traumatic dislocations of the shoulder with open epiphyses. J PediatrOrthop1983;3:61-2.

9. Hong S, Nho JH, Lee CJ, Kim JB, Kim B, Choi HS. Posterior shoulder dislocation with ipsilateral proximal humerus Type 2 physeal fracture: Case report. J PediatrOrthop Part B 2015;24:215-8.

10. Kawam M, Sinclair J, Letts M. Recurrent posterior shoulder dislocation in children: The results of surgical management. J PediatrOrthop1997;17:533-8.

|

|

|

| Dr. R. Dukan | Dr. Y. Ouchrif | Dr. C. Glorion |

| How to Cite This Article: Dukan R, Ouchrif Y, Glorion C. Traumatic posterior shoulder dislocation during judo in a child and literature review. Journal of Orthopaedic Case Reports 2020 May-June;10(3): 43-46. |

[Full Text HTML] [Full Text PDF] [XML]

[rate_this_page]

Dear Reader, We are very excited about New Features in JOCR. Please do let us know what you think by Clicking on the Sliding “Feedback Form” button on the <<< left of the page or sending a mail to us at editor.jocr@gmail.com