[box type=”bio”] Learning Point of the Article: [/box]

[box type=”bio”] Learning Point of the Article: [/box]

Surgery in adult lumbar spine with Langerhans cell histiocytosis is indicated in patients with neurological deficits, instability and intractable pain.

Case Report | Volume 10 | Issue 9 | JOCR December 2020 | Page 28-32 | Charanjit Singh Dhillon, Raviraj Tantry, Shrikant Rajeshwari Ega, Chetan Pophale, Narendra Reddy Medagam, Nilay Chhasatia. DOI: 10.13107/jocr.2020.v10.i09.1892

Authors: Charanjit Singh Dhillon[1], Raviraj Tantry[1], Shrikant Rajeshwari Ega[1], Chetan Pophale[1], Narendra Reddy Medagam[1], Nilay Chhasatia[1]

[1]Department of Spine services, MIOT International, Chennai. Tamil Nadu, India.

Address of Correspondence:

Dr. Raviraj Tantry,

Flat No E-20,Bhatia Gardens, Manapakkam, Chennai-600125, Tamil Nadu, India.

E-mail: drtantry@gmail.com.

Abstract

Introduction: Introduction: Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH) in spine is a benign disorder that mainly affects children and is rare in adults. The treatment of LCH in adults is still controversial. The literature is drought with reports regarding management of LCH in adults with pathological fracture. We report a case of LCH at L5 vertebra in an adult patient treated with posterior stabilization, decompression, and anterior corpectomy and reconstruction.

Case Presentation: A 30-year-old manual laborer working in Middle East, presented to us with severe pain in the lower back (VAS-8) with the right lower limb radiculopathy for 6 months. Radiological investigations revealed to have a solitary osteolytic lesion with pathological fracture at L5 vertebral body. MRI showed hyperintense lesion in T2 sagittal images and hypointense in T1 sagittal images in L5 vertebral body. PET scan showed metabolically active lesion involving L5 vertebra body and right ischium. CT-guided biopsy from L5 vertebral body was performed, but was inconclusive. The patient underwent surgical management in the form of posterior stabilization L4-S1 and transpedicular biopsy. The sample was sent for frozen section and confirmed the presence of neoplasia but did not provide sufficient information about the nature of pathology. Intraoperatively, the decision was made to do anterior excision biopsy, corpectomy, and reconstruction with titanium mesh cage filled with cement. The precise diagnosis of LCH was established on histopathological examination and confirmed with immunohistochemistry positivity for CD1a and S100. The patient had immediate relief of his back pain and radicular pain. He was able to resume his daily activities at 1 month after the surgery. At 2-year follow-up patient was asymptomatic and no local recurrence was noticed.

Conclusion: Surgical excisionfor LCH in adults should be considered in patients with refractory low back pain with pathological fracture, neurological deficits, or spinal instability.

Keywords: Langerhans cell histiocytosis, lumbar spine, Posterior stabilization and anterior reconstruction

Introduction

Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH) is a rare histiocytic disorder characterized by abnormal proliferation of Langerhans cells, which results in the formation of lesions primarily in the skin, bone, liver, spleen, and lymph nodes [1, 2]. In 1868, Paul Langerhans discovered the epidermal dendritic cells that now bear his name [3]. The exact etiology of LCH remains unknown. Approximately 80% of patients present before the age of 10 years, making this a disease of childhood [4]. Adult LCH is rare and its reported incidence is around one to two cases per million people per year[5]. Spine involvement has been found in approximately 7–15% of cases [6] with a predilection for the thoracic spine (54%) followed by the lumbar (35%) and cervical spine (11%) [7]. Although the features and management of this disease are well known in children, there are no established guidelines for diagnosis and treatment of an adult LCH [8]. We report a case of LCH at L5 vertebrain an adult patient who presented to us with severe refractory back pain with pathological fracture and right lower limb radiculopathy treated with posterior stabilization, transpedicular biopsy, anterior corpectomy and reconstruction.

Case Report

A 30-year-old young male, employed as a manual laborer in Middle East, presented with complaints of low back pain(VAS8) for the past 6 months with restriction of his spinal movements. He also complaints of numbness and paresthesias in the right lower limb. He had a recent history of trauma following which his pain had significantly increased and prevented him from being gainfully employed. No history of fever, weight loss, night sweats, and loss of appetite was reported. Medical history was insignificant.

Physical examination revealed an antalgic gait with localized tenderness over the lumbosacral junction and limitation of lumbar spine movements. Neurological examination revealed hypoesthesia over right L5 dermatome and S1 with weakness of the right extensor hallucis longus and extensor digitorum longus (Medical Research Council – 4/5). Laboratory tests revealed elevated ESR (33mm/h) and CRP(43mg/L). Rest of the hematological investigations including complete blood count, liver function tests and renal function tests were within normal limits.

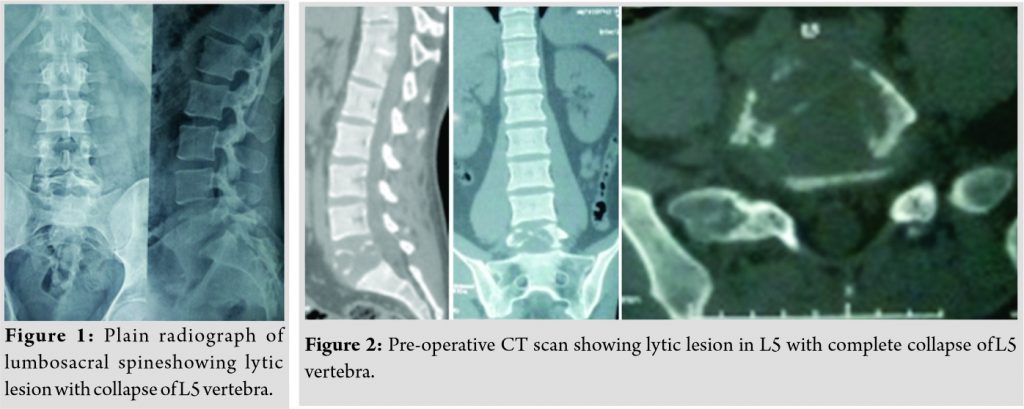

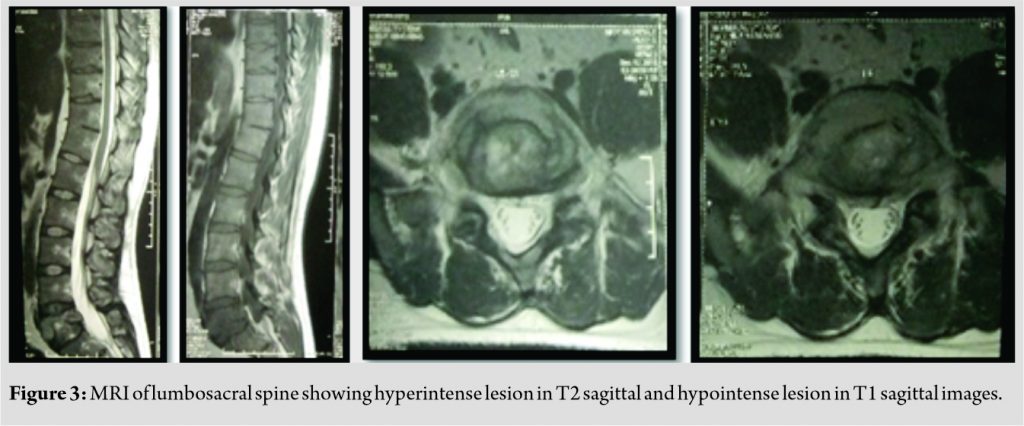

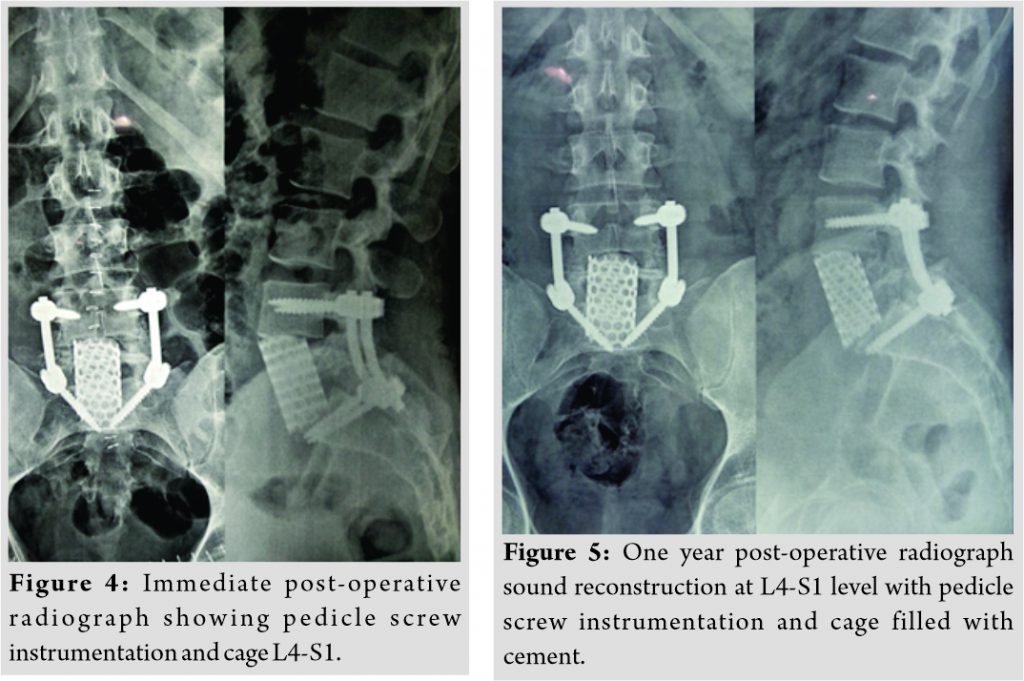

Plain radiograph of lumbosacral spine revealed lytic, non-expansile lesion with pathological fracture at L5 vertebral body (Fig. 1). CT scan showed a well-defined osteolytic lesion involving the entire L5 vertebral body with pathological fracture and intact posterior elements (Fig. 2). There was no reactive osteoblastic activityobvious on CT scan. MRI scan showed hypointense signal changes in TI sagittal and hyperintensesignal changes in T2 sagittal images with normal disc at L4-5and L5-S1 levels (Fig. 3). PET scan showed metabolically active lesion involving L5 vertebral body and right ischium. No obvious primary lesion could be localized on PET scan. On the basis of clinical and diagnostic investigations, a working diagnosis of a neoplastic lesion of L5 vertebra with pathological fracture and 5 radiculopathy was promulgated.

A CT-guided biopsy performed by interventional radiologist from L5 vertebral body. Unfortunately, the reports were inconclusivein histopathology in view of inadequate sample received. The patient was planned for posterior stabilization, laminectomy, decompression and transpedicular biopsy. After ETGA, the patient was positioned prone and a standard midline approach was used to perform posterior stabilization L4-S1 and L5 laminectomy and the decompression of the dural sac and L5 nerve roots bilaterally. Transpedicular biopsy was done and sent for frozen section. The frozen section showed no evidence of infection and revealed features suggestive of atypical neoplasia. However, the nature of neoplasia, whether benign or malignant, could not be concluded from the frozen section. Intraoperatively, the decision was made to do L5 anterior corpectomy, excisionbiopsy, and reconstruction using Harms cage filled with cement strut. The patient was positioned supine and anterior retroperitoneal approach was used to reach the pathologicalL5 vertebra. After adequate vascular mobilization and securement, completeL5 corpectomy was done until the anterior dura was decompressed. The empty corpectomy site was reconstructed with appropriate size titanium Harms cage wedged into lordosis and filled with cement (Fig. 4). Histopathological examination of the biopsy sample showed proliferation of Langerhans cells in sheets and associated with others cells such as eosinophils, lymphocytes, macrophages, and plasma cells and it was reported to be probably LCH. Immunohistochemistry subsequently confirmed the presence of LCH with positive reaction for S100 and Cd1a. Immediately post-surgery, his low back pain and paresthesias in the right lower limb decreased significantly. He was mobilized with lumbosacral belt on the next day after surgery. Since he was having unisystemic bifocal LCH and since he had already undergone compete excision of L5 lesion, the hemato-oncologists opted to treat him with high-dose steroids. The patient came at regular follow-up at the 3rd month, 6th month, and 1 year and 2 years following the surgery. Repeat PET scan done at the 3rd month showed complete resolution ofischial lesion with no tumor uptake at L5 vertebra. At the end of 6 months, implants were holding well without any collapse, recurrence, or any other complications. Final follow-up at the 2nd year showed that the reconstruction was stable with no evidence of loosening or recurrence.

Discussion

LCH is the result of clonal proliferation of immunephenotypical and functionally immature LCH cells, as well as eosinophils, macrophages, lymphocytes, and occasionally multinucleated giant cells [9, 10]. LCH has been reported to be caused by the proliferation and dysregulation of inflammatory cytokines such as interleukin-17 [11,12]. The exact etiology is not established yet. The designation of LCH replaced the previous nomenclature for the group of disorders termed histiocytosis X, which included eosinophilic granuloma (EG), Hand–Schüller–Christian disease (HSCD), and Letterer-Siwe disease (LSD). These conditions vary greatly in presentation and outcome, but share similar pathology of clonal proliferation and accumulation of a specific histiocyte, the Langerhans cell [13].EG is the most common form, reportedly accounting for 60–70% of all cases, usually presenting as solitary bone lesions. EG refers to the localized form of LCH, in which the disease is limited to bone or lung. This is the least aggressive form of the disease, with the most favorable prognosis. HSCD is a chronic, recurring form of LCH, with disseminated disease, affecting both bone and extraskeletal sites. HSCD is known for the classic triad of diabetes insipidus, exophthalmos, and destructive bone lesions. LSD refers to the acute, disseminated, and fulminant form of LCH. This is the least common form of LCH and is predominately described in young children. Patients present with hepatosplenomegaly, lymphadenopathy, skin rash, fever, anemia, and thrombocytopenia. It is rapidly progressive, leading to multiorgan dysfunction and often death within 1–2 years [14,15]. The classification of LCH follows the Histiocyte Society guidelines developed from multicenter randomized trials in children. Classification is based on affected organs and is divided into two categories: Single-system disease or multisystem disease. Single-system disease may be single site (bone, skin, or solitary lymph node) or multisite (multifocal bone disease or multiple lymph nodes). Multisystem disease is further classified into low-risk or risk groups. The low-risk group involves disseminated disease without involvement of vital organs (lungs, liver, spleen, and hematopoietic system). Involvement of one or more risk organs places the patient in the risk group which is associated with the least favorable prognosis [16]. LCH mainly affects children with a peak incidence from 1 to 5 years. The occurrence of LCH is rare with the incidence of 1–2 cases per million per year[5].The most frequently reported anatomic sites are those in the skull(26%), vertebrae(7%),ribs(12%),upper and lower jaw(9%), and bones of extremities(11%) [2, 8]. In the spine, LCH mainly involves the vertebral bodies, with a predilection for the thoracic spine(54%) followed by the lumbar(35%) and cervical spine(11%). In our patient, L5 vertebral body was involved without involvement of the posterior elements. Radiological investigations including the plain radiograph, CT scan revealed aosteolytic lesion in the vertebral body causing collapse of the vertebral body. LCH typically exhibits hypointensity on T1W and hyperintensity on T2W images and moderate enhancement on contrast MR images [17-19]. Routine radiological studies, such as X-ray, CT, and MR imaging, are able to identify osseous lesions but have little value in differentiating LCH from other osteolytic tumors. PET/CT is sensitive to detect hypermetabolic lesions and multiple involvements of LCH. The specificity of these investigations is low and none of them can lead to a definite diagnosis of LCH [20]. A definitive diagnosis of LCH can be made by histopathological study of the biopsy. A CT-guided or fluoroscopy-guided percutaneous needle biopsy can give a definitive diagnosis in 82–90% of cases of LCH. Still, there are a considerable number of cases that cannot be precisely diagnosed in needle biopsy. This may be due to either inadequate tissue sample obtained with needle biopsy or lack of typical cellular findings in histological study [21, 22]. The differential diagnosis for a lytic medullary bone lesion includes benign entities, such as non-ossifying fibromas, bone cysts, or osteomyelitis, but also includes malignant tumors, such as metastases, Ewing sarcoma, and lymphoma. There is no consensus regarding treatment of LCH involving the spine in an adult patient. The various treatment options including observation, nonsteroidalanti-inflammatory drugs, chemotherapy, radiotherapy, intralesional steroid and surgery in the form of excision of the tumor and reconstruction of spine have been reported [8]. In our study, CT-guided biopsy was inconclusive and considering the indolent pain, pathological fracture, andneurological involvement. The patient was offered the surgical treatment in the form of posterior stabilization L4-S1,transpedicular biopsy, and decompression. Unfortunately, the frozen section did not give definitive diagnosis about the nature of pathology. Intraoperatively, the decision for anterior corpectomy, excision biopsy, and reconstruction of anterior weight-bearing column with Harms cage wedged into lordosis and filled with bone cement were made to facilitate any post-operative radiotherapy or chemotherapy if required. The pain and the paresthesias immediately reduced after the surgery and were mobilized comfortably on the next day. The patient got back to his activities of daily living within a month. Since our patient had single system bifocal disease, the hemato-oncologists advised to treat him with high-dose steroids postoperatively. He came for regular follow-up and at the final follow-up at 2 years, there was no local recurrence, implant loosening, and reconstruction failure or any other complications.

Conclusion

LCH in adult spine is a rare disease and has to be considered as one of the differential diagnoses for an osteolyticlesion involving the vertebral body. Surgical treatment should be considered for patients having pathological fracture, neurological deficits, spinal instability and refractory pain that do not respond to conservative treatment.

Clinical Message

In adult Langerhans cell histiocytosis, Surgery in the form of posterior stabilization, decompression and anterior reconstruction can restore the normal biomechanics in lumbosacral spine.

References

1. Imashuku S, Shioda Y, Kobayashi R, Hosoi G, Fujino H, Seto S, et al. Neurodegenerative central nervous system disease as late sequelae of Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Report from the Japan LCH study group. Haematologica 2008;93:615-8.

2. Derenzini E, Fina MP, Stefoni V, Pellegrini C, Venturini F, Broccoli A, et al. MACOP-B regimen in the treatment of adult Langerhans cell histiocytosis: Experience on seven patients. Ann Oncol 2010;21:1173-8.

3. Langerhans P. Uber die nerven der menschlichen haut. Virchows Arch A Pathol Anat Histopathol 1868;44:325-37.

4. Reddy PK, Vannemreddy PS, Nanda A. Eosinophilic granuloma of spine in adults: A case report and review of literature. Spinal Cord 2000;38:766-8.

5. Andersson By U, Tani E, Andersson U, Henter JI. Tumor necrosis factor, interleukin 11, and leukemia inhibitory factor produced by Langerhans cells in Langerhans cell histiocytosis. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 2004;26:706-71.

6. Cañadell J, Villas C, Martinez-Denegri J, Azcarate J, Imizcoz A. Vertebral eosinophilic granuloma. Long-term evolution of a case. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1986;11:767-9.

7. Sayhan S, Altinel D, Erguden C, Kizmazoglu C, Guray M, Acar U. Langerhans cell histiocytosis of the cervical spine in an adult: A case report. Turk Neurosurg 2010;2:409-12.

8. Girschikofsky M, Arico M, Castillo D, Chu A, Doberauer C, Fichter J, et al. Management of adult patients with Langerhans cell histiocytosis: Recommendations from an expert panel on behalf of Euro-Histio-Net. Orphanet J Rare Dis 2013;8:72.

9. Yu RC, Chu C, Buluwela L, Chu AC. Clonal proliferation of Langerhans cells in Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Lancet 1994;343:767-8.

10. Allen CE, Li L, Peters TL, Leung HC, Yu A, Man TK, et al. Cell-specific gene expression in Langerhans cell histiocytosis lesions reveals a distinct profile compared with epidermal Langerhans cells. J lmmunol 2010;184:4557-67.

11. Badalian-Very G, Vergilio JA, Degar BA, MacConaill LE, Brandner B, Calicchio ML, et al. Recurrent BRAF mutations in Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Blood 2010;116:1919-23.

12. Jang KS, Jung YY, Kim SW. Langerhans cell histiocytosis causing cervical myelopathy in a child. J Korean Neurosurg Soc 2010;47:458-60.

13. Mohd Ariff S, Joehaimey J, Ahmad Sabri O, Zulmi W. Langerhans cell histiocytosis with extensive spinal and thyroid gland involvement presenting with quadriparesis: An unusual case in an adult patient. Malays Orthop J 2011;5:28-31.

14. Stull MA, Kransdorf MJ, Devaney KO. Langerhans cell histiocytosis of bone. Radiographics 1992;12:801-23.

15. Lichtenstein L. Histiocytosis X (Eosinophilic granuloma of bone, Letterer-Siwe disease, and Schueller-Christian disease). Further observations of pathological and clinical importance. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1964;46:76-90.

16. Stockschlaeder M, Sucker C. Adult Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Eur J Haematol 2006;76:363-8.

17. Ippolito E, Farsetti P, Tudisco C. Vertebra plana. Long-term follow-up in five patients. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1984;66:1364-8.

18. Kilborn TN, Teh J, Goodman TR. Paediatric manifestations of Langerhans cell histiocytosis: A review of the clinical and radiological findings. Clin Radiol 2003;58:269-78.

19. Paxinos O, Delimpasis G, Makras P. Adult case of Langerhans cell histiocytosis with single site vertebral involvement. J Musculoskelet Neuronal Interact 2011;11:212-4.

20. Chen L, Chen Z, Wang Y. Langerhans cell histiocytosis at L5 vertebra treated with en bloc vertebral resection: A case report. World J Surg Oncol 2018;16:96.

21. Yasko AW, Fanning CV, Ayala AG, Carrasco CH, Murray JA. Percutaneous techniques for the diagnosis and treatment of localized Langerhans-cell histiocytosis (Eosinophilic granuloma of bone). J Bone Joint Surg Am 1998;80:219-28.

22. Huang WD, Yang XH, Wu ZP, Huang Q, Xiao JR, Yang MS, et al. Langerhans cell histiocytosis of spine: A comparative study of clinical, imaging features, and diagnosis in children, adolescents, and adults. Spine J 2013;13:1108-17.

|

|

|

|

|

| Dr. Charanjit Singh Dhillon | Dr. Raviraj Tantry | Dr. Shrikant Rajeshwari Ega | Dr. Chetan Pophale | Dr. Narendra Reddy Medagam |

| How to Cite This Article: Dhillon CS, Tantry R, Ega SR, Pophale C, Medagam NR, Chhasatia N. Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis in the Adult Lumbar Spine – A Case Report and Literature Review. Journal of Orthopaedic Case Reports 2020 December;10(9): 28-32. |

[Full Text HTML] [Full Text PDF] [XML]

[rate_this_page]

Dear Reader, We are very excited about New Features in JOCR. Please do let us know what you think by Clicking on the Sliding “Feedback Form” button on the <<< left of the page or sending a mail to us at editor.jocr@gmail.com