• Children with back pain should be investigated thoroughly with a careful assessment of the red flag signs.

• Regional MRI along with whole body MRI is essential in early diagnosis of CRMO and to pick up asymptomatic lesions. It may also help in avoiding unnecessary invasive diagnostic tests. Importantly, infection and malignancy should be excluded.

• NSAIDS form first line of treatment, however, in resistant cases methotrexate, bisphosphonates and corticosteroids may be used.

Mr. Dheeraj Batheja,

Department of Spinal Disorders, The Robert Jones and Agnes Hunt Orthopaedic Hospital,

Gobowen, Oswestry, SY10 7AG, United Kingdom.

E-mail: drdheerajmamc@gmail.com

Introduction: Chronic recurrent multifocal osteomyelitis (CRMO) is a rare autoimmune disorder of childhood and adolescence which often manifests as recurring episodes of inflammatory bone pains. Spinal involvement is rare; however, recent studies advocate full body magnetic resonance imaging in all suspected cases to pick up asymptomatic lesions early to prevent complications. Spinal involvement may manifest as fractures, scoliosis, or kyphotic deformity.

Case Report: We present a case of a 12-year-old boy who had three-level involvement of thoracic spine, T6-T8, and was worked up and managed for pathological fracture of spine. He underwent biopsy for the same and was later diagnosed as CRMO. Here, we discuss the diagnostic challenges involved in CRMO, need for biopsy, and the management options available.

Conclusions: Identifying CRMO is challenging and remains a diagnosis of exclusion. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs often constitute the first line of treatment and other drugs such as bisphosphonates and biologics such as TNF-alpha antagonists are reserved for more severe cases. Although CRMO is considered a benign disease, recent data suggest up to 50% rate of residual impairments despite optimal management.

Keywords: Chronic recurrent multifocal osteomyelitis, spine, contiguous, child.

Chronic recurrent multifocal osteomyelitis (CRMO) is a rare autoimmune disorder of childhood and adolescence [1]. It is a non-infective osteomyelitis which predominantly affects the metaphysis of the long bones, pelvic, and shoulder girdle and rarely involves mandible and spine [2]. Lack of specific signs and symptoms on examination and imaging makes it a diagnosis of exclusion. The diagnosis of CRMO is often delayed with some studies reporting an average lag of 18 months [3]. It is understood that true prevalence of this entity is underestimated, as it often goes undiagnosed [4]. Here, we share our experience of a 12-year-old boy who presented with chief complaints of recurrent back pain and was later diagnosed as CRMO. There have been few case reports of isolated and non-contiguous fracture of spine in setting of CRMO, but none with contiguous three-level involvement, as per the authors knowledge.

We would like to report this unusual case of three consecutive vertebral body collapse, which turned out to be CRMO. Awareness of this case along with detailed imaging will help orthopedic and pediatric doctors to maintain a high degree of suspicion in cases of atypical osteomyelitis.

A 12-year-old boy, previously well, presented to the spine clinic with a 6-month history of recurrent back pain following a trivial trauma. Pain was acute in onset and was associated with band-like sensation across the chest. It was particularly worse in the night and woke him up from the sleep several times. Family did not report any history of fever or history suggestive of neurological deficit.

He was a keen cricket player which he had to stop due to pain in his ankles and heels. He was later diagnosed with the possible Sever’s disease and was managed conservatively for the same. The parents also noticed the presence of pustules on palms in the past, which have now healed. There was a travel history to the United States of America for 16 days, however, no known history of tick bite or contact with a tuberculosis patient. Birth and development history were unremarkable. There were no pets in the house and no one in the family had a similar clinical presentation in the past.

On examination, he was 138.3 cm tall and weighed 43.25 kg (body mass index [BMI] 22.7 kg/m2, at risk for overweight according to CDC growth charts [5]). He was afebrile to touch and there was no tenderness on palpating the back. He had a mild kyphotic deformity in the mid-back region though his overall spinal alignment was good in both coronal and sagittal planes. He had a relatively preserved spinal range of motion. Abdominal reflexes were bilaterally symmetrical and equal. There was no sensory or motor deficit present in the lower limbs.

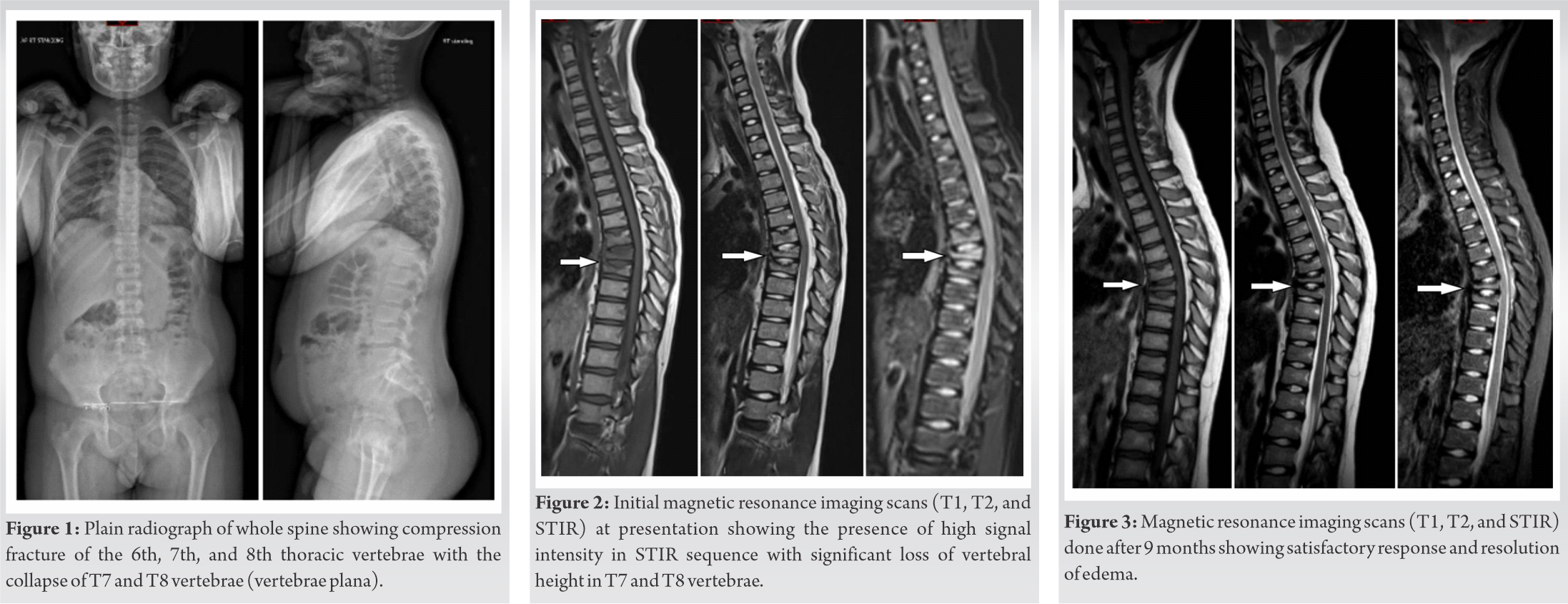

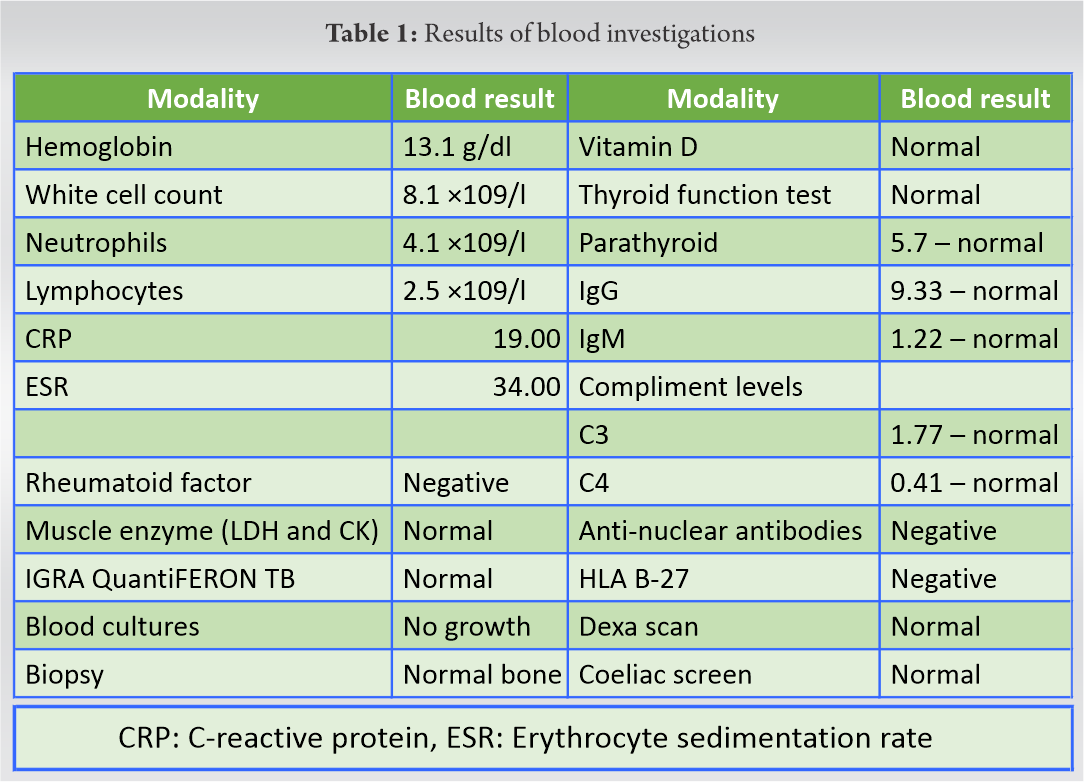

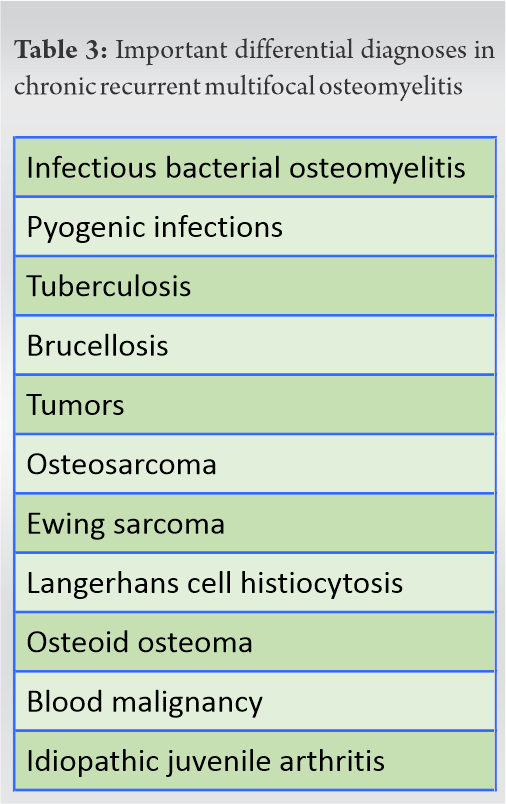

The radiographs of the thoracic spine revealed compression fracture of the 6th, 7th, and 8th thoracic vertebrae with the collapse of T7 and T8 vertebrae (Fig. 1). His blood counts were unremarkable and are tabulated in Table 1. Blood tests were also performed to rule out inflammatory arthropathies. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans were suggestive of high signal intensity in STIR sequence with significant loss of vertebral height in T7 and T8 vertebrae (Fig. 2).

The MRI scan of whole body did not show lesion in any other bone. As no diagnoses was reached on non-invasive investigations, decision to undergo a biopsy was taken in a multi-departmental team MEETING. Subsequently, biopsy was performed under computed tomography (CT) guidance which on pathological examination showed “mainly compacted bone, likely to be normal cortical bone.”

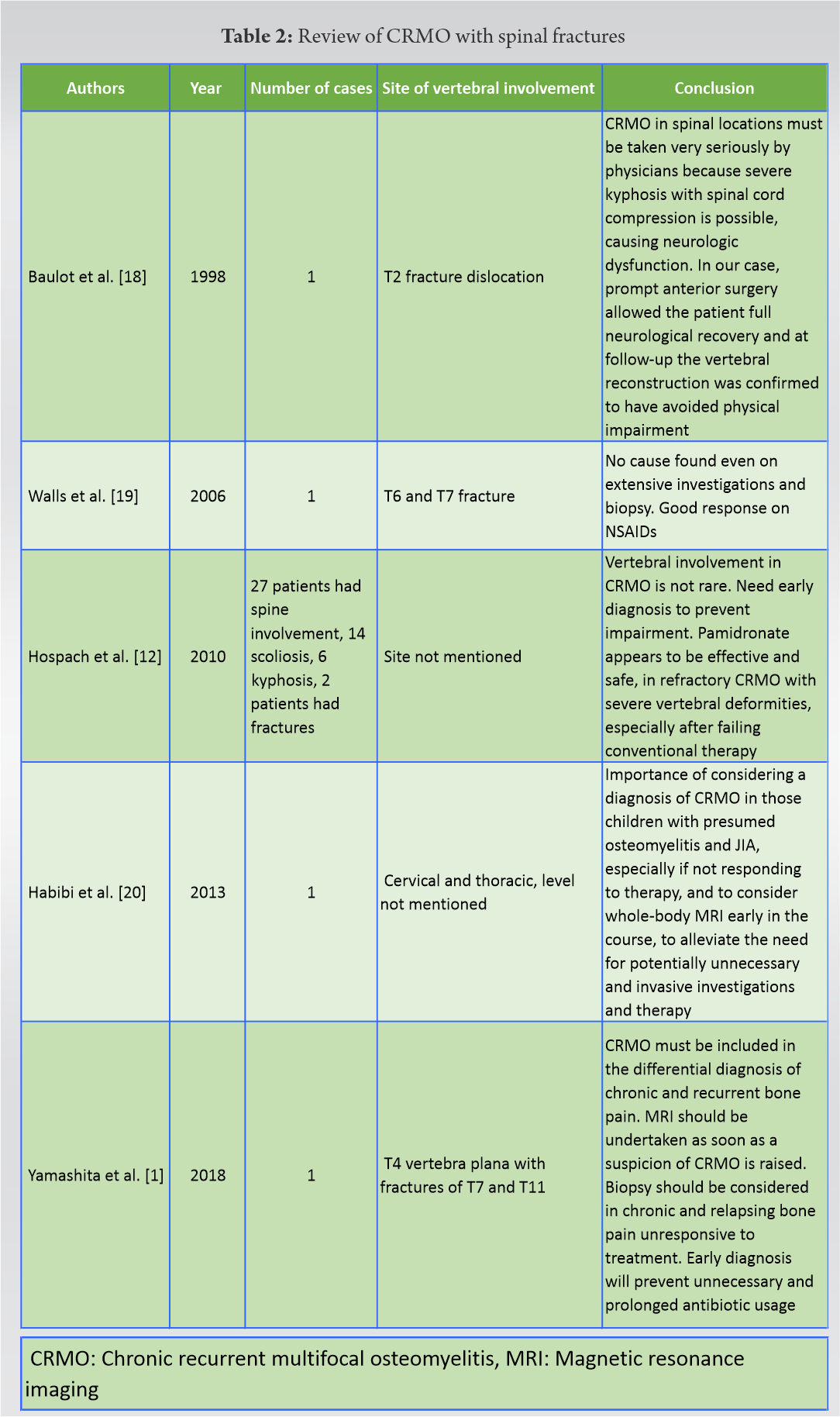

After ruling out all other possibilities, a diagnosis of CRMO was made. He was treated with bisphosphonates and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). The child was pain free after 3 months of treatment. MRI scans done after 9 months revealed satisfactory response as well (Fig. 3). The patient was followed up for 18 months and had complete resolution of symptoms.

CRMO is a rare autoimmune disease of childhood and adolescence which was first described by Giedion et al. [6] in 1972 as chronic symmetrical osteomyelitis. It was later named as CRMO by Probst et al. [7], as he noticed that some of the cases did not have symmetrical distribution. The usual age of child at the onset of disease is around 10 years and varies from 4 to 14 years [8]. There is a female predilection with female-to-male ratio ranging from 2.4:1 to 4:1 [8]. Some authors also consider CRMO to be a pediatric form of synovitis, acne, pustulosis, hyperostosis, and osteitis syndrome [9]. Exact etiology of this disease is still unknown, but it is found to be associated with psoriasis, inflammatory arthritis, inflammatory bowel disease, Majeed syndrome, and Sweet syndrome [10]. It is not uncommon to see a diagnostic delay of several months from appearance of first symptoms and final diagnosis. According to one study, it takes up to 18 months for the diagnosis to be made [3].

Most common manifestation of CRMO are painful bony lesions mainly affecting the metaphysis of the long tubular bones. Tibia is the most common affected bone involving both distal and proximal metaphyseal regions followed by the distal femur and pelvic bones [11].

Other locations include humerus, clavicle, and spine. According to Hospach et al. [12], spine is involved in up to 37% of cases, however rarely diagnosed. There are some case reports of mandibular involvement as well.

On reviewing the literature, we found that there have been few case reports of isolated and non-contiguous fracture of spine in setting of CRMO but none with contiguous three-level involvement. We have summarized the reports and series describing various spine fractures in setting of CRMO in Table 2.

CRMO patients (usually children) often present with a recurrent episodes of bone pains and localized increased temperature which may last for days to weeks. Some patients may be asymptomatic. High persistent fever or septic history is not usually seen and, if present, should warrant ruling out bacterial osteomyelitis. Some of these patients also develop extraosseous manifestations, especially in the case of long-standing disease or severe disease [11]. In such cases, decreased range of motion and deformities may be seen around the joints. These may be in the form of limb length discrepancies, especially in the area of proximal tibial or distal femur [11].

In cases of spine, asymmetrical destruction with scoliosis, vertebral plana, and pathological fractures after trivial trauma has been described [1]. In most instances, this is self-limiting and lesions heal at the time of puberty.

In addition to the history, detailed physical examination is necessary. Examination of palms and soles may reveal the presence of pustules. Psoriatic patches may also be seen on face and near hairline. Detailed evaluation is required to rule out other diagnosis such as inflammatory arthropathies and infection. During the acute phase, C-reactive protein and erythrocyte sedimentation rate and fibrinogen level may be raised, but these are non-specific. Blood cultures, biopsy, and other tests are often deemed necessary to rule out other diagnosis and as mentioned in Table 3. All other possible diagnoses should be ruled out before labeling it as CRMO.

Conventional X-rays of the long bones may be normal in up to one-third of patients. Remaining patients show changes in the metaphysis, usually 2–3 weeks after onset of symptoms. Lesions, typically, are lytic in nature surrounded by sclerotic margins but not pathognomonic. Isolated lytic or sclerotic lesions have also been described [11]. X-rays of the spine may reveal acute fractures or deformities such as scoliosis and kyphosis depending on the nature and the site of involvement.

MRI is often necessary to visualize early changes. Full body MRI scans are being used for diagnosis and follow-up. In contrast to MRI of the involved bone, whole-body MRI can be used to pick up asymptomatic spine lesions and thus prove useful in managing such lesions before complications ensue [11]. CT scan should only be used in the rare cases with severe destruction of the bones for pre-operative surgical planning to plan for the reconstruction.

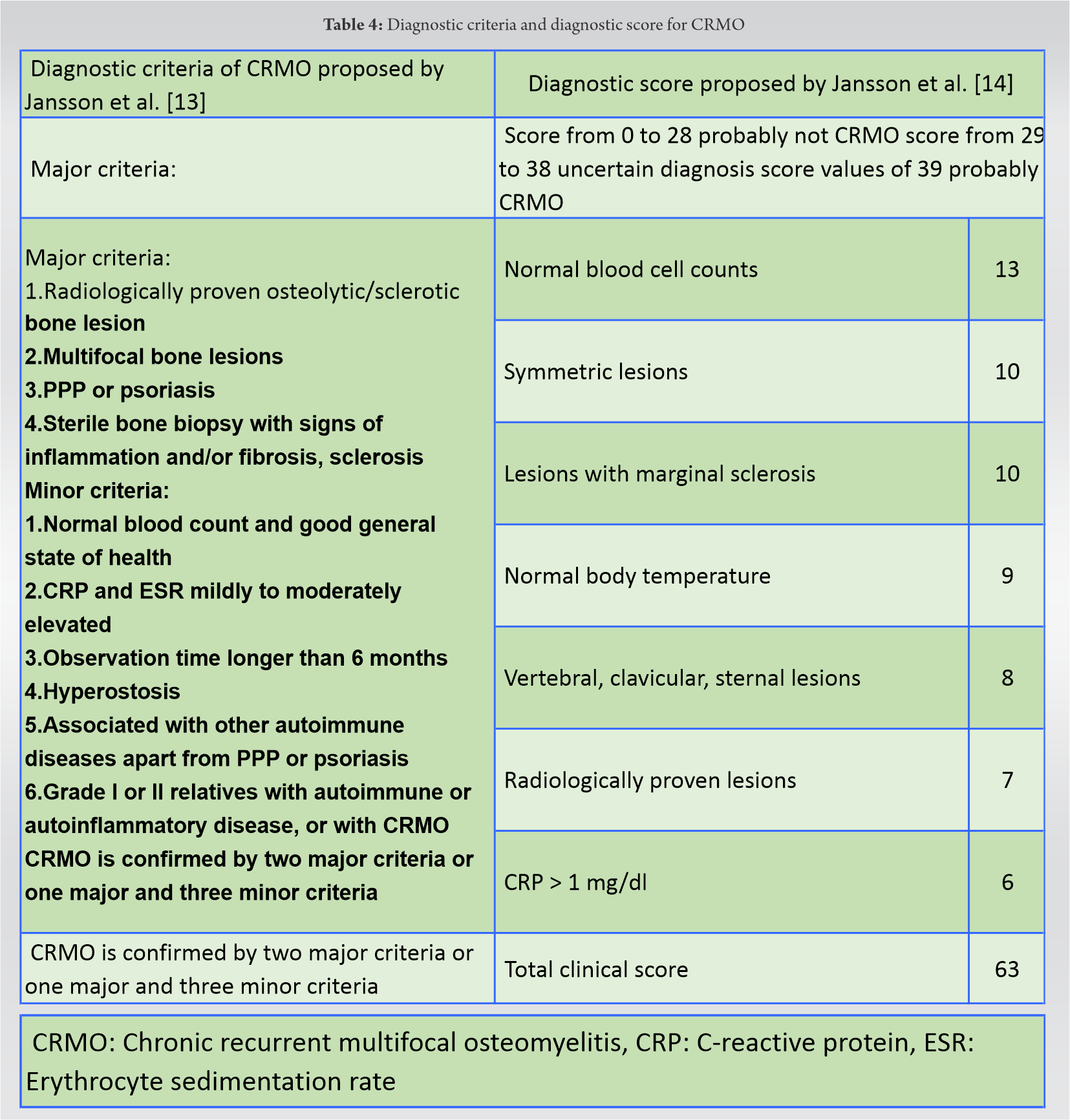

Biopsy is used to exclude the contentious diagnosis. As mentioned, CRMO is a diagnosis of exclusion and hence biopsy is invariably required to rule out remaining differential diagnosis. Since the biopsy is an invasive procedure, it can be a traumatic experience for a young child. Jansson et al. [13] developed a clinical pathway to avoid unnecessary punctures. A score and a flowchart are used. The score was developed retrospectively from a cohort of 224 patients, including 120 patients with CRMO and other bone diseases (bacterial osteomyelitis, benign and malignant bone diseases). On a scale of 0–63, mixed weightage is given to the variables, as depicted in Table 4. Following the path, the need and timing of a biopsy can be decided together with the score. Jansson et al. [14] also published diagnostic criteria to differentiate non-bacterial osteitis from other bone lesions, which are also applicable in the setting of a CRMO and suggested four major and six minor criteria. CRMO is confirmed by two major criteria or one major and three minor criteria (Table 4).

Management of CRMO requires a multidisciplinary approach, with a team of experienced pediatrician, pediatric rheumatologists, pediatric spine, and may be pediatric psychologist on the board. Supportive management in the form of NSAIDs is the first line of therapy and is usually effective in majority of cases [15]. Role of other drugs is still debatable. Further treatment with immunosuppressants such as azathioprine, methotrexate, TNFs receptor antagonists, and bisphosphonates has been described in various studies of recurrent or severe CRMO cases and found to have good therapeutic value [16, 17]. Azithromycin, a macrolide antibiotic, has also been used along with calcitonin because of its anti-inflammatory properties. Recently, there have been encouraging reports on the role of bisphosphonates in management of CRMO [17]. However, there are no randomized control trials and therefore no concrete recommendation for its use.

The duration of the therapy depends on the symptoms. It is recommended to continue therapy for 3 months after the symptoms have subsided. Patients should remain asymptomatic over this period. After that, patients are gradually weaned of these drugs [16]. To summarize, risk–benefit ratio should be weighed in individually and side effects considered before giving long duration of any drugs indicated in CRMO, which is naturally self-limiting and benign. In addition to pharmacotherapy, physiotherapy and cryotherapy also play an important role in management of these patients [17]. There is no available literature on the use of a spine corset in the setting of CRMO. Operative measures are only required to perform a biopsy. A surgical procedure in the case of resulting misalignment of the spine by CRMO has not been described in any series or case reports except one. This was one case in the series described by Baulot et al. [18] which had dislocation in upper thoracic spine in setting of CRMO and was managed with anterior surgery along with pharmacotherapy.

CRMO is a disease of childhood and adolescence. Treating clinicians should be familiar with this entity and it should be kept in the differential diagnosis in cases presenting with atypical osteomyelitis, unifocal, or multifocal. Whole-body MRI must be done to know about other asymptomatic sites and treatment should be started before any complication ensues. Prompt diagnosis of CRMO will allow patients to avoid the risks associated with lengthy courses of antibiotic therapy and repeat bone biopsies.

Children presenting with back pain should be investigated thoroughly with a careful assessment of red flag signs. If CRMO is suspected, regional MRI along with whole-body MRI should be performed to aid in early diagnosis and to pick up asymptomatic lesions. It may also help in avoiding unnecessary invasive diagnostic tests. Importantly, infection and malignancy should be excluded. NSAIDs form first line of treatment, however, in resistant cases methotrexate, bisphosphonates, and corticosteroids may be used.

References

- 1.Yamashita K, Calderaro C, Labianca L, Gajaseni P, Weinstein SL. Chronic recurrent multifocal osteomyelitis (CRMO) involving spine: A case report and literature review. J Orthop Sci 2021;26:300-5. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gamble JG, Rinsky LA. Chronic recurrent multifocal osteomyelitis: A distinct clinical entity. J Pediatr Orthop 1986;6:579‐84. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wipff J, Adamsbaum C, Kahan A, Job-Deslandre C. Chronic recurrent multifocal osteomyelitis. Joint Bone Spine 2011;78:555‐60. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schnabel A, Range U, Hahn G, Siepmann T, Berner R, Hedrich CM. Unexpectedly high incidences of chronic non-bacterial as compared to bacterial osteomyelitis in children. Rheumatol Int 2016;36:1737‐45. [Google Scholar]

- 5.CDC Growth Charts: United States; 2020. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/growthcharts. [Last accessed on 2020 Jul 28]. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Giedion A, Holthusen W, Masel LF, Vischer D. Subacute and chronic “symmetrical” osteomyelitis. Ann Radiol (Paris) 1972;15:329‐42. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Probst FP, Björksten B, Gustavson KH. Radiological aspect of chronic recurrent multifocal osteomyelitis. Ann Radiol (Paris) 1978;21:115‐25. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Huber AM, Lam PY, Duffy CM, Yeung RS, Ditchfield M, Laxer D, et al. Chronic recurrent multifocal osteomyelitis: Clinical outcomes after more than five years of follow-up. J Pediatr 2002;141:198‐203. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Prose NS, Fahrner LJ, Miller CR, Layfield L. Pustular psoriasis with chronic recurrent multifocal osteomyelitis and spontaneous fractures. J Am Acad Dermatol 1994;31:376‐9. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wipff J, Costantino F, Lemelle I, Pajot C, Duquesne A, Lorrot M, et al. A large national cohort of French patients with chronic recurrent multifocal osteitis. Arthritis Rheumatol 2015;67:1128‐37. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Falip C, Alison M, Boutry N, Job-Deslandre C, Cotten A, Azoulay R, et al. Chronic recurrent multifocal osteomyelitis (CRMO): A longitudinal case series review. Pediatr Radiol 2013;43:355‐75. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hospach T, Langendoerfer M, von Kalle T, Maier J, Dannecker GE. Spinal involvement in chronic recurrent multifocal osteomyelitis (CRMO) in childhood and effect of pamidronate. Eur J Pediatr 2010;169:1105‐11. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jansson AF, Müller TH, Gliera L, Ankerst DP, Wintergerst U, Belohradsky BH, et al. Clinical score for nonbacterial osteitis in children and adults. Arthritis Rheum 2009;60:1152‐9. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jansson A, Renner ED, Ramser J, Mayer A, Haban M, Meindl A, et al. Classification of non-bacterial osteitis: Retrospective study of clinical, immunological and genetic aspects in 89 patients. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2007;46:154‐60. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hofmann SR, Kapplusch F, Girschick HJ, Morbach H, Pablik J, Ferguson PJ, et al. Chronic recurrent multifocal osteomyelitis (CRMO): Presentation, pathogenesis, and treatment. Curr Osteoporos Rep 2017;15:542‐54. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Taddio A, Zennaro F, Pastore S, Cimaz R. An update on the pathogenesis and treatment of chronic recurrent multifocal osteomyelitis in children. Paediatr Drugs 2017;19:165‐72. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sułko J, Ebisz M, Bień S, Błażkiewicz M, Jurczyk M, Namyślak M. Treatment of chronic recurrent multifocal osteomyelitis with bisphosphonates in children. Joint Bone Spine 2019;86:783‐8. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Baulot E, Bouillien D, Giroux EA, Grammont PM. Chronic recurrent multifocal osteomyelitis causing spinal cord compression. Eur Spine J 1998;7:340‐3. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Walls T, Bate J, Moshal K. Vertebral collapse in an 8-year-old girl. J Paediatr Child Health 2006;42:212‐4. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Habibi S, Thompson E, Thyagarajan MS, Ramanan AV. Unusual presentation of spinal involvement in a child with chronic recurrent multifocal osteomyelitis. Int J Rheum Dis 2013;16:477‐9. [Google Scholar]