A heightened awareness of scurvy is needed to avoid unnecessary surgery, unnecessary tests, and procedures and to be able to start treatment for a potentially fatal but easily curable disease.

Dr. Parimal K Malviya,

Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, MGM Medical College and Hospital, Navi Mumbai, Maharashtra, India. E-mail: dr.parimal90@gmail.com

Introduction: Scurvy is a rarely seen in pediatric patients nowadays, seen more in those with developmental delay, autism or those who are severely malnourished. Epiphyseal separations are known to occur in scurvy, but only a few such cases have been reported in children with cerebral palsy. The diagnosis is often misleading since other morbidities as trauma, malignancies, coagulopathies, septic arthritis, osteomyelitis, or rheumatologic disorders are often considered at first. We report the case of 4-year-old female child with cerebral palsy in whom the initial concern was septic arthritis/osteomyelitis based upon clinical presentation, ultrasonic and magnetic resonance imaging, led to a surgery revealing subperiosteal hematomas.

Case Report: A 4-year-old girl was admitted in the pediatrics department for fever and bilateral knee joint pain for 3 days. She was a diagnosed case of with cerebral palsy, psyco-developmental delay, and epileptogenic disorder put under valproic acid. She was toxic and febrile. Within 4 h after admission, both knees developed tense shiny intense swelling associated with pain, redness, and local rise of temperature with limited active range of motion. Near-complete passive range of motion was noted. There were no abnormal findings on the rest of the musculoskeletal examination. Aspiration of the knee revealed subperiosteal hematoma diagnostic of scurvy.

Conclusion: Scurvy is exceedingly rare in children nowadays; however, its presentation among risky populations should not be forgotten. Musculoskeletal revelations, mostly subperiosteal hematoma, are the main manifestation of scurvy in the pediatric population. Scurvy as a differential diagnosis for trauma, osteomyelitis, septic arthritis will always be a bane for orthopedic surgeons. A heightened awareness is needed to avoid unnecessary surgery, unnecessary tests, and procedures and to be able to start treatment for a potentially fatal but easily curable disease.

Keywords: Scurvy, cerebral palsy, septic arthritis, pediatric, multiple epiphyseal separations.

Although infrequent, scurvy continues to be seen today within certain populations, such as the elderly subjects, patients with neurological delay or psychiatric affections, or others with unusual alimentary diet. Scurvy is a rare condition in pediatric patients, more seen in those with a developmental delay or autism, and some studies have found a correlation between infant scurvy and milk pasteurization which denatures Vitamin C [1, 2]. Musculoskeletal manifestations are prominent in pediatric scurvy [3] and occur in 80% of patients [1, 4]. We can find nonspecific arthralgias, myalgia, hemarthrosis, muscular hemorrhage, and subperiosteal hematomas. These symptoms are more common in the lower extremities and the knee is the most affected joint [1]. The rarity and the polymorphisms of the clinical signs make scurvy an often-unknown diagnosis [5]. Here, we report a case of scurvy in a 4-year-old girl with cerebral palsy in whom the initial concern was for osteomyelitis, based on clinical presentation, ultrasonic and magnetic resonance imaging, led to a surgery revealing subperiosteal hematomas.

A 4-year-old girl was admitted in the pediatrics department for fever and bilateral knee joint pain for 3 days. Suspecting septic arthritis, empirical antibiotics were started. The child was born pre-term and weighed 1600 g with a context of acute fetal distress. She was diagnosed with cerebral palsy, psyco-developmental delay, and epileptogenic disorder put under valproic acid. She was non ambulant with severe spastic paraplegia and incontinence of stool and urine.

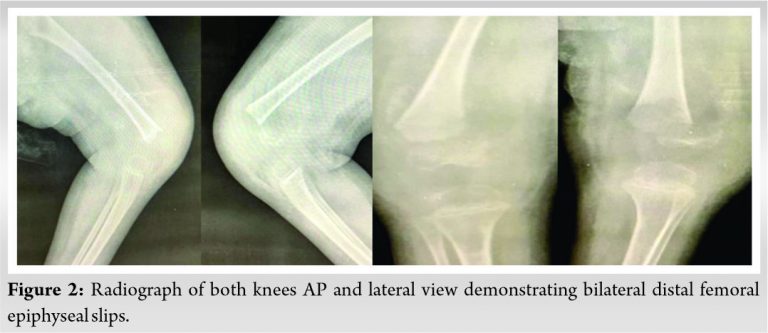

Upon physical examination, the patient’s weight was less than the third percentile; she was also pale and has marked anxiety to strangers. She was febrile (38.8°C), had a pulse of 124, blood pressure 100/64 mm Hg, and respiratory rate of 22. Oral examination shows poor dental hygiene but the skin was normal. One day after admission, she developed bilateral knee bruising and swelling (Fig. 1) with limited active motion range, pain on palpation of distal femur metaphysis. Near complete passive range of motion was noted. There were no abnormal findings on the rest of the musculoskeletal examination. The biological samples showed the following results: total leukocyte count: 9220, platelets count 440000/μL, hemoglobin: 5 g/dL (microcytic hypochromic anemia), blood sedimentation rate >140 mm/h and a C-reactive protein of 90 mg/dL. A low level of iron was seen with a rate of 7 micro-mole/l (11 to 27 micromole/l). Alkaline phosphatase, calcium, and phosphate levels were normal. Radiograph of the knee shows signs of osteopenia, an irregular thickened white line at the upper tibial metaphysis, a zone of rarefaction under the same metaphysis, and a periosteal reaction. Furthermore, it showed dislocation of bilateral distal femoral epiphyses. Dense, linear calcification in thedistal metaphysis “white line of Frankel” and periosteal separation was noticed (Fig. 2).

Ultrasound of both knees showed infiltration and denseness of the soft tissues with detachment of the periosteum. Knee magnetic resonance imaging was performed and interpreted as osteomyelitis of the left distal femur with subperiosteal abscess associated with an articular effusion of the knee joint. Orthopedic surgeon was consulted for the concern of osteomyelitis. The orthopedic surgeon with the above-mentioned clinical picture mentioned the following differentials in decreasing order of importance -Trivial trauma, Septic arthritis, osteomyelitis. A surgery was quickly considered (because the clinical picture of sepsis was so overwhelming) and the aspiration of the collection by a needle bringing back a gelatinous red fluid (Fig. 3) After the surgical approach, it was clear that the collection interpreted as abscess was just a subperiosteal hematoma without any sign of infection. Intravenous Oxacillin and Gentamicin were started. Bacterial cultures from the needle aspirate were negative and antibiotics were stopped. The bone biopsy showed signs suggestive of a recent subperiosteal bleeding and abnormality of the collagen matrix, which was suggestive of scurvy. In the absence of the technical board, the level of Vitamin C was not available. More detailed questioning was made to get an idea about the dietary habits. It showed that the child was fed by his mother only with milk products. The child was placed under an oral supplementation of Vitamin C at a dose of 500 mg per day. His mother was informed about dietary modification. 3 weeks after vitamin C therapy, the child’s pain and the general condition improved.

Vitamin C is essential for humans and intimately concerned in the maintenance of intercellular connective tissue and stabilization of collagen triple helix [6, 7]. Since the human body is unable to synthesize Vitamin C, its dietary intake must be in sufficient amounts [4, 7]. Collagen abnormalities, caused by lack of Vitamin C explain the clinical manifestations of scurvy: stomatological deformations and the fall of teeth, vascular fragility causing bleeding and purpura, bone changes (in children) due to the inability of osteoblasts to produce the osteoid matrix, and skin changes related to the poor quality of keratin [7, 8]. Although rare, scurvy in pediatric patients still appears. Scurvy is seen in babies fed with cow’s milk due to the pasteurization process that denature the ascorbate [1, 2]. Despite its rarity, recent reports have highlighted cases of scurvy in children with neurological pathology and poorly adapted diet [9]. A review of the English medical literature made by Harknett et al. showed 18 cases of scurvy in pediatrics patients who had been diagnosed with autism and neuro-developmental delay with limited food preferences [1]. The study made by Noble et al. [10] has shown 23 cases of scurvy in children with behavioral disorders, including children with autism and children with cerebral palsy. The initial manifestations are non-specific such as irritability, loss of appetite, low-grade fever, and later dermatological such as petechiae, ecchymoses, hyperkeratosis, and corkscrew hairs [11]. Then, chronic bleeding is seen in areas where the blood vessels are superficial or areas where the contraction of muscles is enough to traumatize already defective blood vessels. The major systemic signs of scurvy in children include fatigue, weight loss, loss of appetite, and anxiety [2]. Biological findings are not specific. Anemia is frequent and may be hypochromic, normocytic, or macrocytic. Although bleeding may contribute to induce anemia, the main factor is concomitant iron and folic acid deficiency. Scurvy was not one of the differentials also because the clinical picture of sepsis was overwhelming that the surgeon was forced to intervene. The definite diagnosis is achieved by determining the serum ascorbic acid level. Furthermore, measuring the vitamin C level in the buffy coat of the leucocytes is a better estimate of the Vitamin body stores. However, this method is technically demanding and not always available. Due to its multiple differential diagnosis, scurvy is difficult to diagnose, but there is a useful mnemonic for remembering many of its common presentations is 4 “H”: hemorrhagic signs, hyperkeratosis, hematologic abnormalities, and hypochondriasis.

Scurvy is exceedingly rare in children nowadays; however, its presentation among risky populations should not be forgotten. Musculoskeletal revelations, mostly subperiosteal hematoma, are the main manifestation of scurvy in the pediatric population. Scurvy as a differential diagnosis for trauma, osteomyelitis, septic arthritis will always be a bane for orthopedic surgeons. A heightened awareness is needed to avoid an unnecessary surgery, unnecessary tests, and procedures and to be able to start treatment for a potentially fatal but easily curable disease.

A heightened awareness is needed to avoid an unnecessary surgery, unnecessary tests, and procedures and to be able to start treatment for a potentially fatal but easily curable disease.

References

- 1.Harknett KM, Hussain SK, Rogers MK, Patel NC. Scurvy mimicking osteomyelitis: Case report and review of the literature. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 2014;53:995-9. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Popovich D, McAlhany A, Adewumi AO, Barnes MM. Scurvy: Forgotten but definitely not gone. J Pediatr Health Care 2009;23:405-15. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Besbes LG, Haddad S, Ben Meriem C, Golli M, Najjar M, Guediche MN. Infantile scurvy: Two case reports. Int J Pediatr 2010;2010:717518. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Polat AV, Bekci T, Say F, Bolukbas E, Selcuk MB. Osteoskeletal manifestations of scurvy: MRI and ultrasound findings. Skeletal Radiol 2015;44:1161-4. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Allgaier RL, Vallabh K, Lahri S. Scurvy: A difficult diagnosis with a simple cure. Afr J Emerg Med 2012;2:20-3. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Agarwal A, Shaharyar A, Kumar A, Bhat MS, Mishra M. Scurvy in pediatric age group a disease often forgotten? J Clin Orthop Trauma 2015;6:101-7. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aghajanian P, Hall S, Wongworawat MD, Mohan S. The roles and mechanisms of actions of Vitamin C in bone: New developments. J Bone Miner Res 2015;30:1945-55. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fain O. Musculoskeletal manifestations of scurvy. Joint Bone Spine 2005;72:124-8. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weinstein M, Babyn P, Zlotkin S. An orange a day keeps the doctor away: Scurvy in the year 2000. Pediatrics 2001;108:E55. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Noble JM, Mandel A, Patterson MC. Scurvy and rickets masked by chronic neurologic illness: Revisiting “psychologic malnutrition”. Pediatrics 2007;119:e783-90. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brickley M, Ives R. Skeletal manifestations of infantile scurvy. Am J Phys Anthropol 2006;129:163-72. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Riepe FG, Eichmann D, Oppermann HC, Schmitt HJ, Tunnessen WW Jr. Special feature: Picture of the month. Infantile scurvy. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2001;155:607-8. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gulko E, Collins LK, Murphy RC, Thornhill BA, Taragin BH. MRI findings in pediatric patients with scurvy. Skeletal Radiol 2015;44:291-7. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brennan CM, Atkins KA, Druzgal CH, Gaskin CM. Magnetic resonance imaging appearance of scurvy with gelatinous bone marrow transformation. Skeletal Radiol 2012;41:357-60. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Duggan CP, Westra SJ, Rosenberg AE. Case records of the Massachusetts general hospital. Case 23-2007. A 9-year-old boy with bone pain, rash, and gingival hypertrophy. N Engl J Med 2007;357:392-400. [Google Scholar]