There is an increased risk of COVID induced coagulopathy in the third trimester, hence these patients must be managed by a multidisciplinary team in a tertiary care facility.

Dr. Chandan Noel Vincent, Department of Orthopaedics, PSG Institute of Medical Sciences and Research, Coimbatore, Tamil Nadu, India. E-mail: chandannoel@gmail.com

Introduction:Pregnancy is a physiologically hypercoagulable state and a coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) infection adds to this burden by accentuating the coagulopathy. We report two cases of severe peri-partum COVID infection leading to extremity gangrene secondary to a pro-thrombotic coagulopathy.

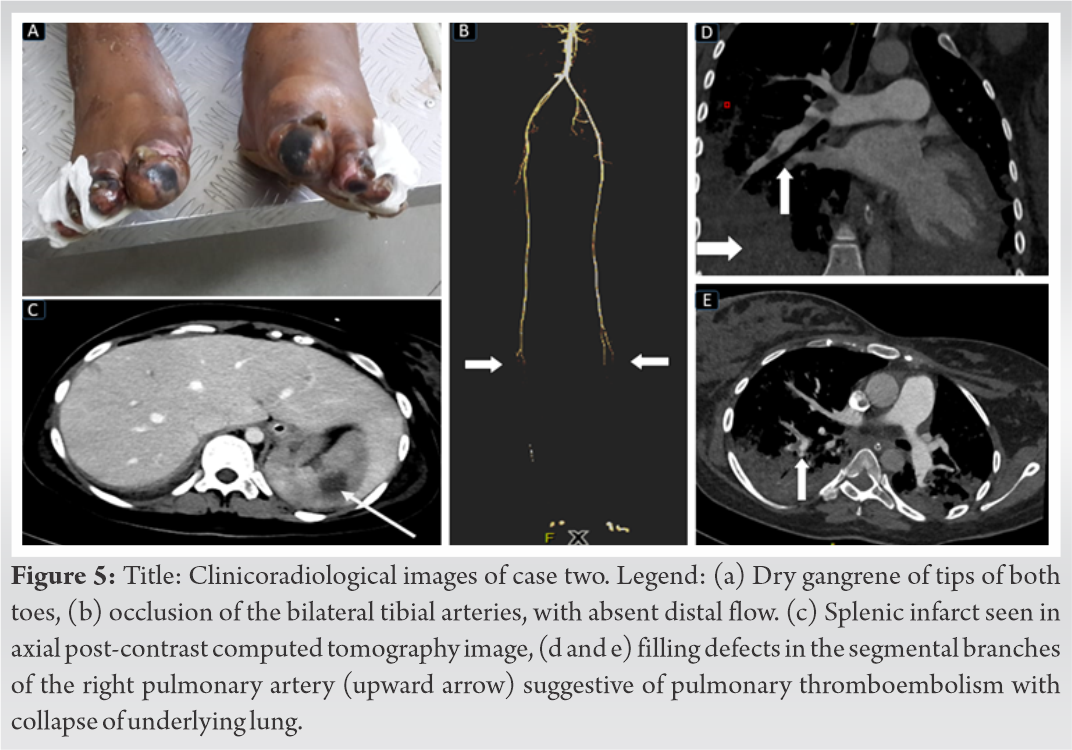

Case Report:A 37-year-old lady, day-2 postpartum, was brought with severe COVID infection & and respiratory failure. She developed progressive gangrene of the foot. A computed tomography (CT) angiogram confirmed the presence of thrombosis of the left external iliac & and common femoral artery. She was managed with catheter- directed thrombolysis and fasciotomy. The dry gangrene of the foot was managed with a Boyd’s amputation. At 1-year follow-up, she is ambulant with a healthy stump. Case Two: A 34-year-old lady, 36 weeks of gestation, presented with fulminant COVID infection with respiratory failure and pulmonary embolus. The lady developed gangrene of the B/L toes. A CT angiogram revealed thrombosis below the popliteal trifurcation in both limbs along with segmental pulmonary thrombo-embolism involving the right lung and multiple splenic infarcts. She succumbed to the overwhelming infection and sepsis.

Discussion:The pathogenesis of coagulopathy in pregnant COVID patients is attributed to the hypercoagulable effect, which leads to thrombo-embolisms and limb ischemia following a cytokine storm syndrome in severe infections. To date, this is the first experience detailing distal limb gangrene in fulminant COVID infection in peri-partum women. Although, cases have been reported on distal limb gangrene in severe COVID infection among non-pregnant individuals.

Conclusion:A multidisciplinary team must manage COVID infections in the third trimester. A prompt recognition of any forms of lethal coagulopathy and vigilant treatment will prevent loss of life.

Keywords:Coronavirus diseaseCOVID, foot gangrene, pregnancy, coagulopathy.

Pregnancy is a physiologically hypercoagulable state and a coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) infection adds to this burden by accentuating the coagulopathy. Especially, the last trimester of pregnancy carries significant risks in the form of altered pulmonary function and immune response. These changes occur as the body works toward restoration of hemostasis postpartum by establishing a hypercoagulable state and altering the inflammatory responses [1]. Khalil et al., in a recent systematic review and meta-analysis of 2567 pregnancies across 86 studies, found 73.8% of the women requiring admission to be in the third trimester. In their analysis, maternal mortality was 1%. However, 7% of the women required ICU admission given a severe infection and 3.4% required mechanical ventilation [2].

The risk of pre-term birth, intrauterine growth retardation, and maternal mortality are well-documented complications of COVID-19 in pregnancy [2, 3, 4, 5]. However, there are not many articles describing coagulopathy in the third trimester/perinatal women. In most of the women admitted to intensive care unit, it is fulminant with the women succumbing before a diagnosis of coagulopathy can be established [6, 7, 8, 9]. Herein, we report two cases wherein fulminant peripartum COVID-19 infection with cytokine storm syndrome led to an accelerated prothrombotic coagulopathy, leading to lower extremity gangrene.

Case one

A 37-year-old woman was referred to our institution with fever and breathlessness for the past 10 days, which had progressively worsened. She had delivered a healthy male baby, following an emergency cesarean section due to the progressive breathlessness in an outside hospital. She was referred to our hospital because of a fulminant respiratory failure and reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) confirmed a severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-COV) infection. On clinical examination, she was tachycardic (HR-120), hypotensive, and hypoxic (sp02-80). She had a Grade-2 sacral bedsore, diffuse crepitations on auscultation of both lung fields. She also had pre-gangrenous changes in the left lower extremity involving the toes with a feeble distal pulse and sluggish capillary refill. Investigations revealed a type 1 respiratory failure (pH – 7.28, PO2 – 43, PCO2 – 49, and HCO3 – 22) and grossly elevated inflammatory markers (interleukin-6 – 125 pg/ml, total white cell count – 22,000, lactate dehydrogenase – 837 U/L, D-Dimer – 2.87 mg/ml, and pro-brain natriuretic peptide 2 – 892.3 pg/ml). Computed tomography (CT) scan of the chest revealed ground-glass opacities in bilateral lung fields with peripheral subpleural areas of consolidation (CT severity score 16/25). Due to her deteriorating medical condition, grossly elevated inflammatory markers and acute respiratory distress syndrome secondary to the systemic inflammatory response syndrome – Cytokine storm syndrome, she was resuscitated in the COVID intensive care unit by a multidisciplinary team comprising intensivist, physician, orthopedic surgeon, general surgeon, and obstetrician. She was treated with mechanical ventilation, prone positioning, IV fluids, antiviral therapy – remdesivir, broad-spectrum antibiotics, methylprednisolone, and low-molecular-weight heparins (LMWHs) in therapeutic dosage, and other supportive therapy.

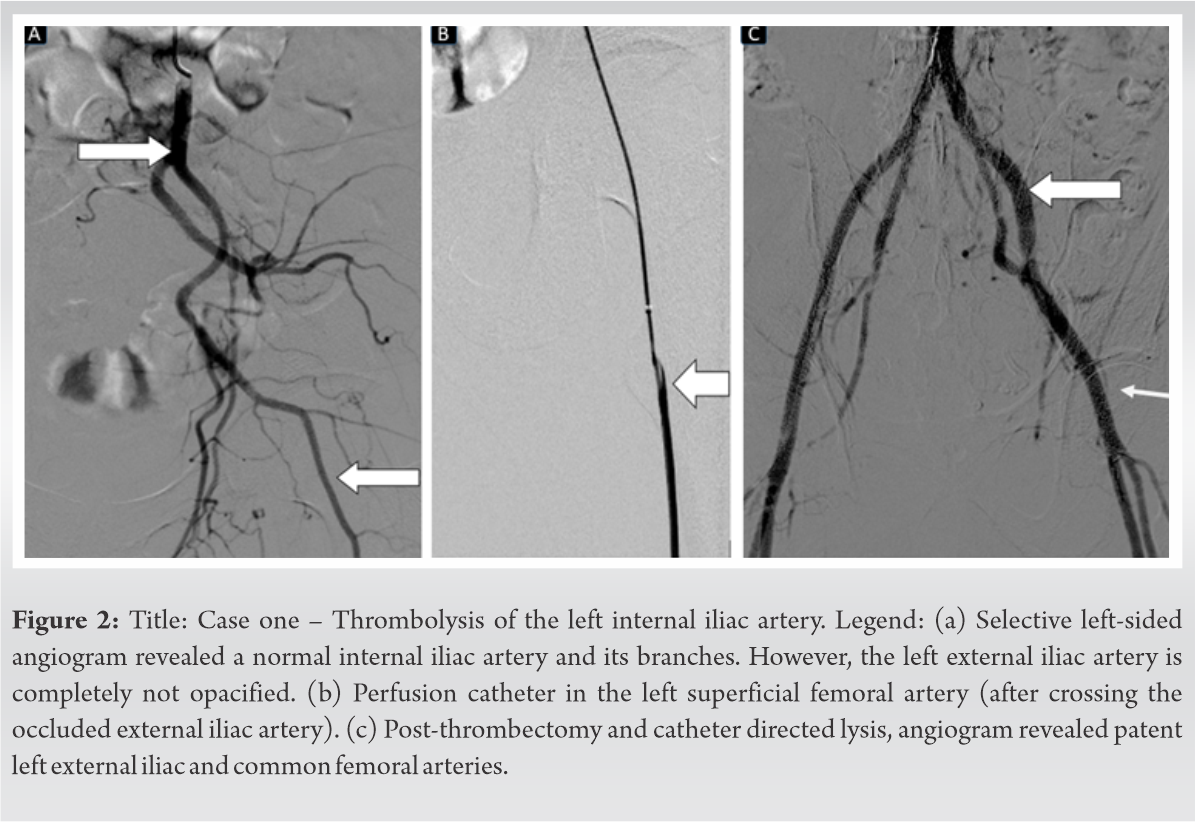

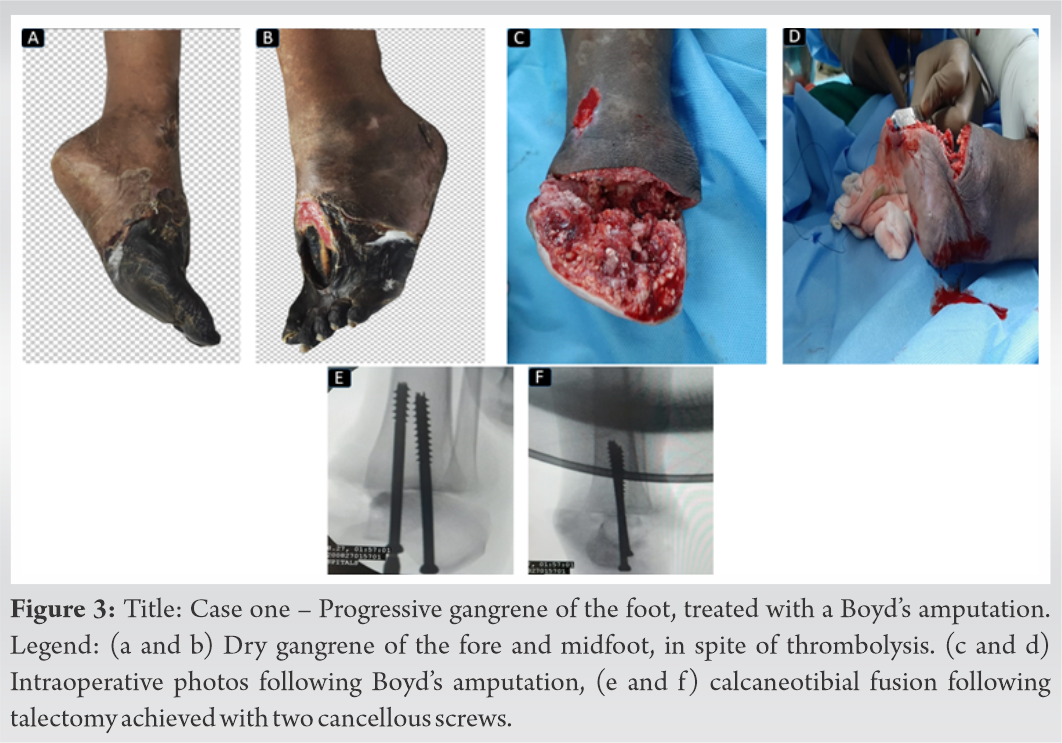

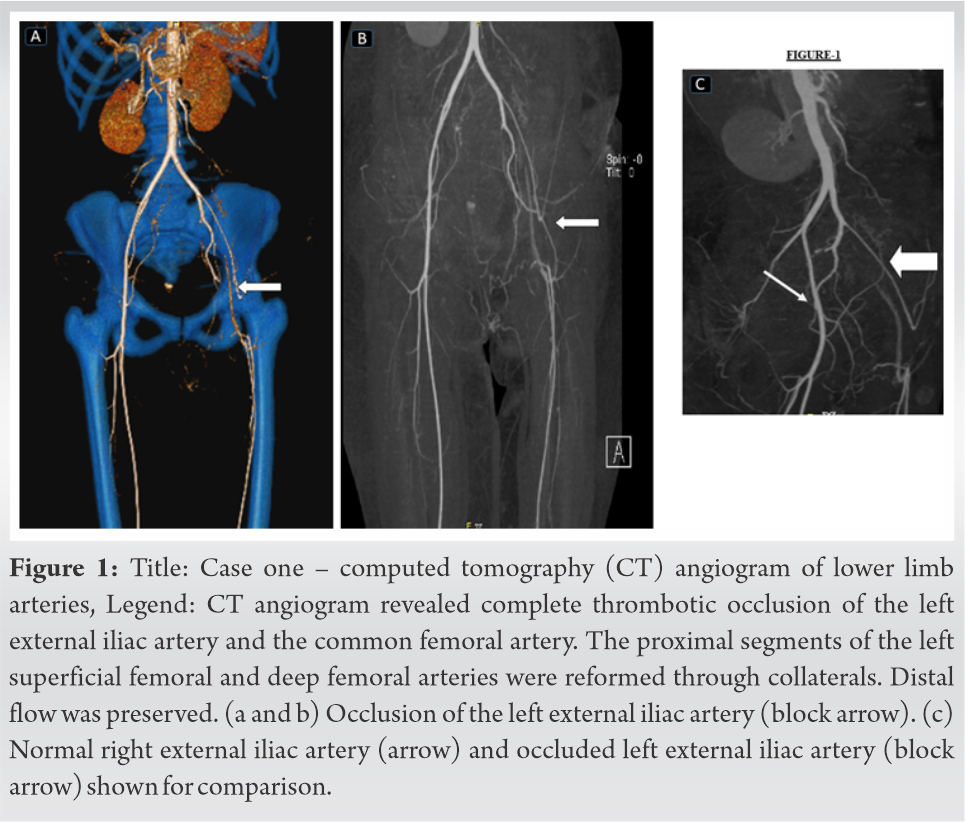

Once her general condition was stable, the interventional radiology team investigated her left lower limb ischemia with a CT angiogram of the extremities and lung. There was no evidence of pulmonary thromboembolism. However, a CT angiogram of the extremities through right femoral access showed loss of flow due to thrombosis of the external iliac and common femoral artery in the left side (Fig. 1).

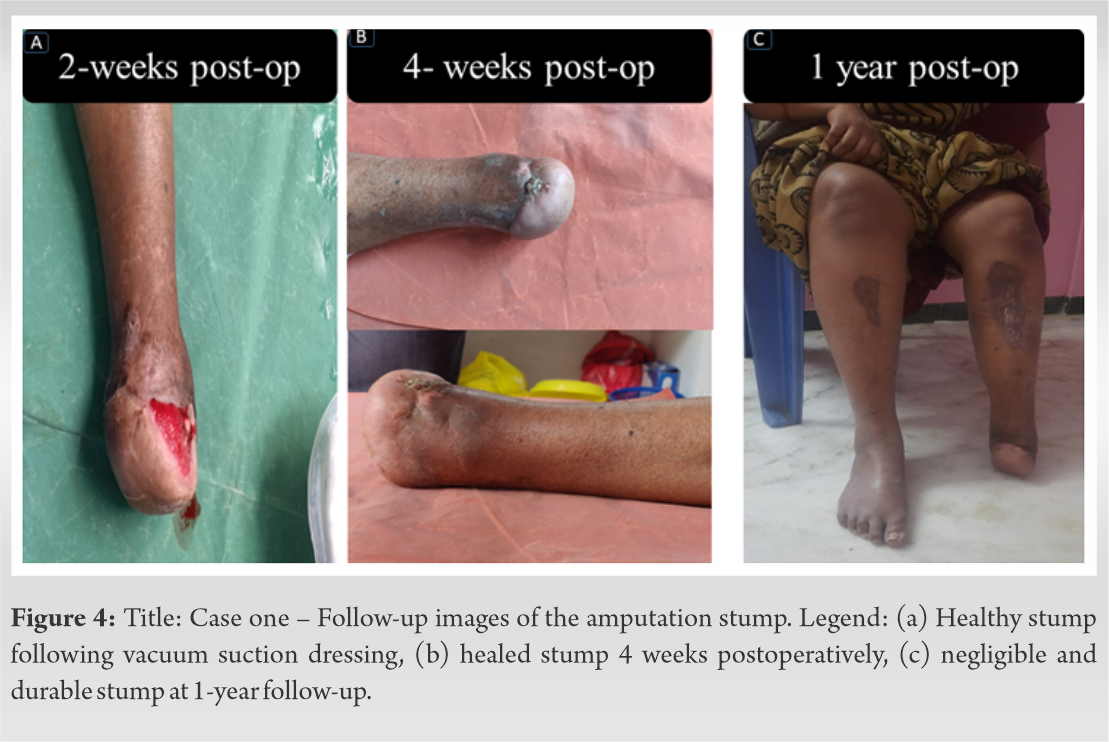

As we waited for the dry gangrene to demarcate, her general condition improved with treatment and she was successfully extubated on day-7 of admission. After she was extubated, in the subsequent days, her lung condition worsened due to a hospital-acquired bacterial pneumonia (Acinetobacter). She was reintubated as she required mechanical ventilatory support due to a respiratory failure, following which she improved with antibiotics and mechanical ventilation and was successfully extubated on day 17, although she continued to require oxygen supplementation. Once her general condition improved, Boyd’s amputation was performed. A fish mouth incision was utilized, the midfoot and forefoot were amputated. A Whitman’s talectomy was done, following which the tibial plafond and malleoli were osteotomized flush with the decorticated tibial articular surface. The calcaneum was osteotomized and decorticated and fused to the tibia with two cancellous screws inserted retrograde (Fig. 3c-f). The heel pad was repaired and a vacuum dressing was applied.

There was no evidence of infection in the amputated stump, which went on to heal with the assistance of vacuum dressings over the next 3 weeks. She was treated with therapeutic oral anticoagulation for 6 months. At the 1 year follow-up, she is ambulant with a prosthesis and ambulates short distances without a prosthesis since her heel is intact. There was a satisfactory fusion of the calcaneotibial stump (Fig. 4).

Case two

A 34-year-old woman (G3P2L1A1), 36 weeks of gestation, presented with fever, cough, and breathlessness of 20 days duration. Clinically, she was tachycardic (125/min), hypotensive (80/40), hypoxic (80%), and drowsy. She had coarse crepitations on auscultation in both lung fields. Although the RT-PCR was negative for a COVID infection, CT chest showed diffuse ground-glass opacities with peripheral consolidations suggestive of COVID pneumonia (CT severity score – 22/25). Laboratory investigations revealed neutrophil leukocytosis with raised inflammatory markers, initial cultures of urine, blood, and sputum turned out to be sterile. She was admitted to the COVID intensive care because of a fulminant respiratory failure, for which she was intubated and mechanically ventilated. She was administered methylprednisolone, remdesivir, broad-spectrum antibiotics, therapeutic LMWH, inotropes, and supportive therapy including prone ventilation.

On day-4 of admission, she had developed gangrene of the toe tips in B/L lower limbs (Fig. 5a) despite anticoagulation, with significant worsening of her lung condition. A CT angiogram revealed thrombosis below the popliteal trifurcation with lack of flow in peroneal, anterior, and posterior tibial arteries. She also had CT evidence of segmental pulmonary thromboembolism involving the right lung and multiple splenic infarcts (Fig. 5b-e).

Based on the reports from Ellington et al. Center for Disease Control-United States of America, pregnant women with a COVID-19 infection are more likely to get hospitalized (31.5), when compared to non-pregnant counterparts (5.8%) [3]. They were more likely to be admitted to the intensive care unit and receive mechanical ventilation (10.5 vs. 3.9 per 1000 cases) [3]. Coagulopathy is one of the complications, which can lead to fatal outcomes in pregnant women with COVID-19 infection. The pathogenesis of coagulopathy in COVID patients is attributed to the hypercoagulable effect secondary to the cytokine response, which leads to thromboembolisms and limb ischemia [10]. There is no accepted consensus on the dosage and indications of venous thromboembolism prophylaxis in pregnant women with COVID infection. Apart from that in most cases of third trimester pregnancies, the coagulation profile can be misleading [11]. Kadir et al. in their meta-analysis suggested weight-adjusted LMWH therapy for all pregnant women admitted with a COVID infection [11].

Wang et al. attributed the onset of ischemia following the viral respiratory infection and progression despite anticoagulation to thrombotic microangiopathy as a consequence of cold-sensitive antibody/immunoglobulin activation in response to the virus [12]. In our case one, there was a progression of the gangrene despite catheter-directed thrombolysis and therapeutic LMWH therapy from day 1 of admission. At the outset, numerous other causes have been attributed like prone positioning, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO), and third trimester of pregnancy, which in itself is a risk factor [12].

There are not many studies, which detail the thrombotic complications of COVID-19 infection in pregnancy. Martinelli et al. described a young woman in her third trimester developing a pulmonary embolism, which was due to a COVID infection-induced coagulopathy. An emergency cesarean section was performed at 29 weeks because of dyspnea and worsening clinical picture, however, the infection was not fatal and the patient recovered well [7]. In our case-2, the pulmonary embolism coupled with a secondary Acinetobacter infection-sepsis was fatal. Mohammadi et al. published in their case report of a woman in her third trimester developing an ovarian vein thrombosis following a COVID infection [9]. Ahmed et al. described a 29-year-old mother in her third trimester with uncontrolled diabetes, developed pulmonary embolism and basilar stroke following a severe COVID infection, which was eventually fatal [8].

To date, the largest meta-analysis of COVID infection in pregnancy is the compilation of 117 studies with 11,758 pregnant women by Karimi et al. The study details morbidity and mortality of COVID infection in pregnant women based on the experiences of numerous afflicted countries. In their extensive research, there was no published experience of distal extremity gangrene in pregnant or postpartum women [13]. To date, this is the first experience detailing distal limb gangrene in fulminant COVID infection in peripartum women. Although, cases have been reported on distal limb gangrene in severe COVID infection among non-pregnant individuals.

Siegel et al., in a case report, illustrated a 31-year-old male with a severe COVID infection on mechanical ventilation and ECMO developing gangrene of the toe tips. In this case, no angiogram was performed to identify a thrombus, furthermore, the gangrene was not progressive. He had recovered with no loss of life and limb [14]. However, in both our cases, an angiogram revealed thrombosis of common femoral and external iliac in case one, thrombosis below the popliteal trifurcation in case two. In case one, the gangrene was progressive despite catheter-directed thrombolysis with streptokinase and finally required Boyd’s amputation. At 1-year follow-up, she is ambulant and independent with no residual vascular complications. Whereas case two, due to the disseminated nature of thromboembolisms, involving multiple organs (lung and spleen), she succumbed to the overwhelming infection and its complications despite treatment.

For case one, we decided to go for Boyd’s amputation in view of preserving the hindfoot en bloc, as the gangrene had already involved the forefoot and parts of the midfoot as well. It is a well-known fact that there is increased cardiac stress with more proximal amputations. Apart from that, cadence and speed of walking decrease with more proximal levels of amputation. In Boyd’s amputation, the heel block is preserved, hence, for short-distance ambulation, the patient needs not be dependent on the cumbersome prosthesis and there is less chance of a soft-tissue failure. More importantly, limb length discrepancy is minimal, hence, energy expenditure is also minimal which makes rehabilitation faster and easier. The single biggest advantage of preserving the heel is that it gives proprioceptive feedback, which helps in improving the gait patterns compared to the more proximal amputations [15].

In our experience, these findings of distal extremity gangrene following COVID infection in pregnancy are rare and not reported. A multidisciplinary team must manage COVID infections in the third trimester. Prompt recognition of any forms of lethal coagulopathy and vigilant treatment will prevent loss of life.

COVID infection in the third trimester is prone to coagulopathies; clinicians must be vigilant in recognizing thrombotic complications, especially in the peripartum women.

References

- 1.Schwartz DA, Graham AL. Potential Maternal and Infant Outcomes from (Wuhan) Coronavirus 2019-nCoV Infecting Pregnant Women: Lessons from SARS, MERS, and Other Human Coronavirus Infections. Viruses 2020;12:194. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Khalil A, Kalafat E, Benlioglu C, O’Brien P, Morris E, Draycott T, et al. SARS-CoV-2 infection in pregnancy: A systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical features and pregnancy outcomes. EClinicalMedicine 2020;25:100446. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ellington S, Strid P, Tong VT, Woodworth K, Galang RR, Zambrano LD, et al. Characteristics of women of reproductive age with laboratory-confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection by pregnancy status-United States, January 22-June 7, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2020;69:769-75. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pierce-Williams RA, Burd J, Felder L, Khoury R, Bernstein PS, Avila K, et al. Clinical course of severe and critical COVID-19 in hospitalized pregnancies: A US cohort study. Am J Obstet Gynecol MFM 2020;2:100134. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen L, Li Q, Zheng D, Jiang H, Wei Y, Zou L, et al. Clinical characteristics of pregnant women with covid-19 in Wuhan, China. N Engl J Med 2020;382:e100. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vlachodimitropoulou Koumoutsea E, Vivanti AJ, Shehata N, Benachi A, Le Gouez A, Desconclois C, et al. COVID19 and acute coagulopathy in pregnancy. J Thromb Haemost 2020;18:1648-52. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Martinelli I, Ferrazzi E, Ciavarella A, Erra R, Iurlaro E, Ossola M, et al. Pulmonary embolism in a young pregnant woman with COVID-19. Thromb Res 2020;191:36-7. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ahmed I, Azhar A, Eltaweel N, Tan BK. First COVID-19 maternal mortality in the UK associated with thrombotic complications. Br J Haematol 2020;190:e37-8. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mohammadi S, Abouzaripour M, Hesam Shariati N, Hesam Shariati MB. Ovarian vein thrombosis after coronavirus disease (COVID-19) infection in a pregnant woman: Case report. J Thromb Thrombolysis 2020;50:604-7. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kasinathan G, Sathar J. Haematological manifestations, mechanisms of thrombosis and anti-coagulation in COVID-19 disease: A review. Ann Med Surg (Lond) 2020;56:173-7. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kadir RA, Kobayashi T, Iba T, Erez O, Thachil J, Kazi S, et al. COVID-19 coagulopathy in pregnancy: Critical review, preliminary recommendations, and ISTH registry-communication from the ISTH SSC for women’s health. J Thromb Haemost 2020;18:3086-98. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang JS, Pasieka HB, Petronic-Rosic V, Sharif-Askary B, Evans KK. Digital gangrene as a sign of catastrophic coronavirus disease 2019-related microangiopathy. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open 2020;8:e3025. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Karimi L, Makvandi S, Vahedian-Azimi A, Sathyapalan T, Sahebkar A. Effect of COVID-19 on mortality of pregnant and postpartum women: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Pregnancy 2021;2021:8870129. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Siegel A, Al Rubaiay A, Adelsheimer A, Haight J, Gawlik S, Oropallo A. Pedal gangrene in a patient with COVID-19 treated with prone positioning and extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. J Vasc Surg Cases Innov Tech 2021;7:357-60. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Saini UC, Rawat SS, Dhillon MS. Syme’s amputation: Do we need it in 2020? J Foot Ankle Surg (Asia Pacific) 2021;8:86-90. [Google Scholar]