Orthopedic surgeons should never miss detailed early neurological examination in patients with both bone forearm fracture

Dr. Rajan Toor, Department of Orthopedics, Holy Spirit Hospital, Mahakali Caves Road, Andheri (E), Mumbai - 400 093, Maharashtra, India. E-mail: dr.rajantoor@gmail.com

Introduction:Ulnar nerve injury in closed both bone forearm fracture is rare. Most nerve injuries are neuropraxia and rarely the nerve is trapped or is transected. Most of the time recovery is spontaneous but sometimes requires surgical exploration. We are reporting a case of a 14-year-old boy with closed both bone forearm fracture with ulnar nerve palsy due to entrapment and laceration between ulnar bone fracture fragment.

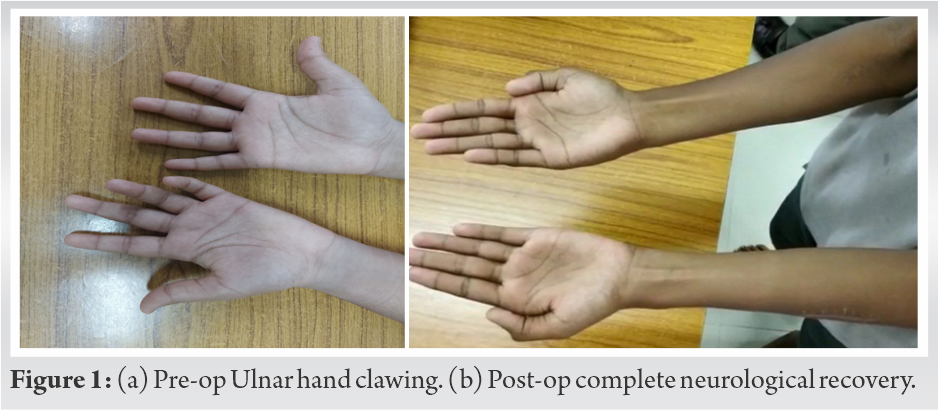

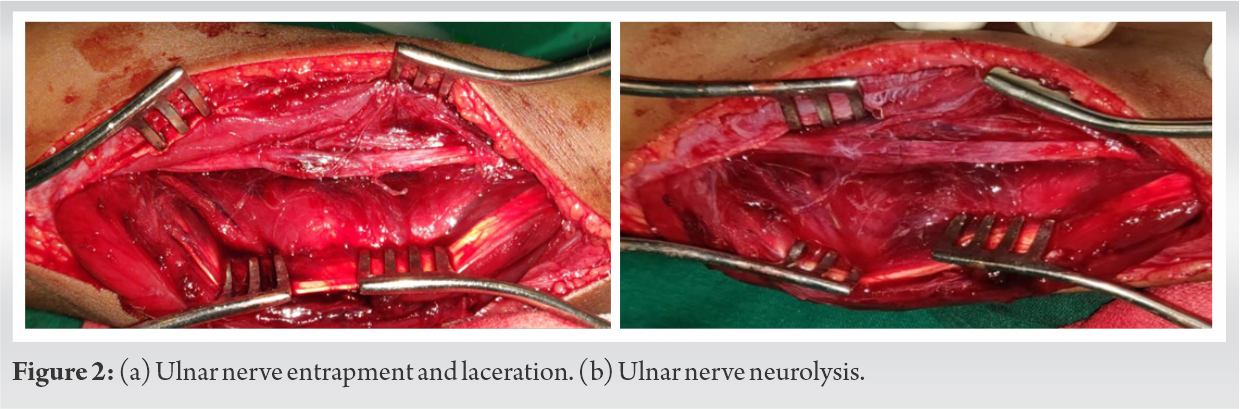

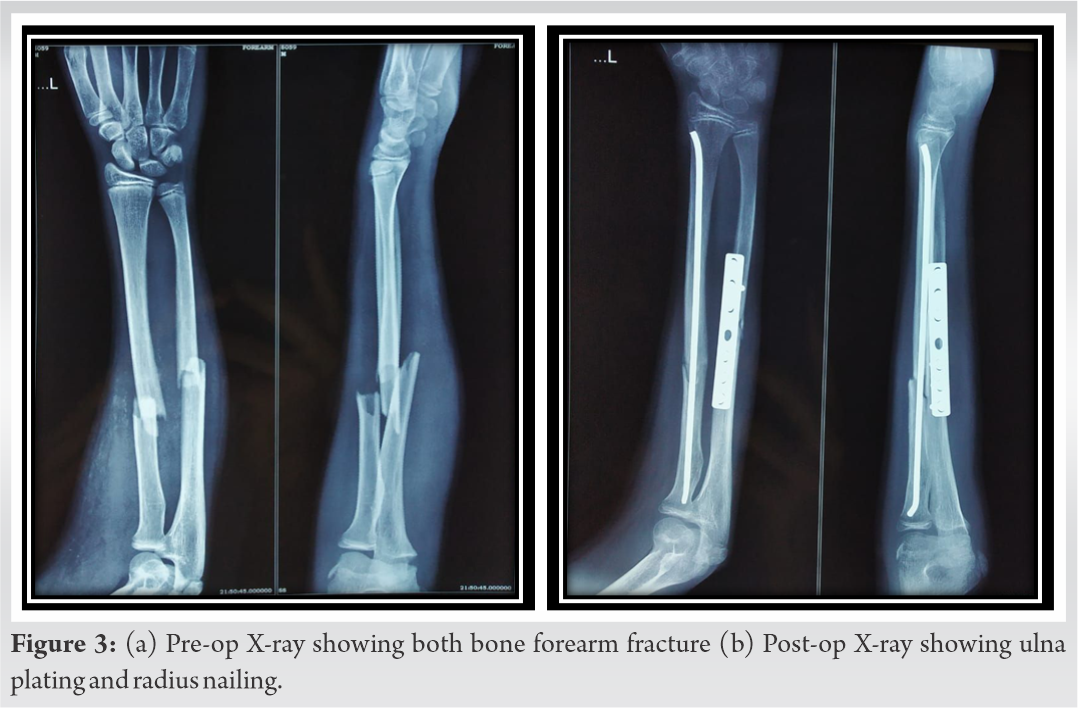

Case Report:A 14-year-old boy presented in emergency department elsewhere with a left forearm closed injury due to fall while playing where he was diagnosed with both bone forearm shaft fracture with ulnar nerve palsy and was given an above elbow slab. After 3 days, the patient presented to our outpatient department (OPD) with completely absent sensation over little finger, ulnar aspect of ring finger, and ulnar clawing. No signs of compartment syndrome in the form of tense swelling or stretch pain were seen. There was a suspected ulnar nerve injury for which patient was admitted and posted for fracture fixation and exploration of the nerve in emergency which showed lacerated ulnar nerve trapped in fracture fragment. Open reduction and internal fixation with ulnar plating and radius titanium elastic nailing was done by orthopedic surgeon while ulnar nerve neurolysis and micro repair was subsequently done by plastic surgeon. There was no neurological recovery immediately post-operatively. Patient was discharged after 48 h and called for regular follow-up in OPD to assess fracture union and neurological recovery. There was gradual neurological recovery over the period of time. Complete motor and sensory recovery took place in 4 months.

Conclusion:Ulnar nerve injury associated with close both bone forearm fracture is uncommon. They are usually associated with a contusion for which the treatment is basically conservative. Immediate nerve exploration and fracture fixation should be reserved for suspicious nerve laceration or entrapment within displaced fracture fragments on radiographs. This prevents delay and also avoids nerve sequelae to occur. Hence, high index of suspicion and complete neurological examination of the patient at first presentation is important to recognize and diagnose the type of nerve lesion early to decide upon the plan of management.

Keywords:Ulnar nerve palsy, both bone forearm fracture, ulnar plating and radius titanium elastic nailing, neurolysis.

Among all fractures in pediatric population, both bone forearm fracture accounts for 30–40% [1]. Nerve injuries are a known complication in these fractures, median nerve being the commonest while ulnar nerve injury is rare [2, 3]. The incidence of neurologic injury with both bone forearm fracture was found to be 15.6%, from which distal physeal fractures accounted for 37% [4]. We have found around 15 published case reports shown in (Table 1). In the literature, exact incidence of these nerve injuries has not been mentioned. Mechanism of injury include direct contusion from the displaced fragment, traction injury while attempting closed reduction, entrapment of nerve at the fracture site, acute compartment syndrome, delayed nerve palsy due to nerve getting adhered to scar tissue. The most common pathophysiology is neuropraxia while laceration and transection occur rarely [1]. Mostly recovery is spontaneous but sometimes surgical exploration of the nerve during fracture fixation may be required in cases of worsening neuropraxia or suspected nerve entrapment and laceration at the fracture site [5]. Before any manipulative reduction of forearm fractures in children, a proper neurologic examination should be done to identify the type of nerve damage and plan its management [6, 7]. Here, we are reporting a case of a 14-year-old boy with closed both bone forearm shaft displaced fracture with ulnar nerve palsy due to laceration following entrapment between fracture fragments.

A 14-year-old boy presented in emergency department elsewhere with left forearm closed injury due to fall while playing where he was diagnosed with both bone forearm shaft fracture shown in Fig. 1a with ulnar nerve palsy and was given an above elbow slab.

Most of the pediatric closed both bone forearm fractures are conservatively managed with closed reduction and casting. Surgical intervention is done in open fractures, failed or unstable reductions, segmental fractures, neurovascular injuries, and skeletally mature individuals [8]. Ulnar nerve injury in closed both bone forearm fractures is a rare entity [9]. Till date around 15 cases have been documented in the literature as shown in (Table 1).

Anatomically the ulnar nerve runs parallel to the flexor digitorum profundus muscle deep to flexor carpi ulnaris muscle on the forearm protected by the surrounding muscle and is therefore rarely contused directly by an external force. However, the nerve being close to the ulna at middle and distal thirds; any significant angulation and displacement with a bone spike can directly injure the nerve [10]. Certain specific fracture patterns such as apex volar angulation, a proximal ulnar oblique fragment at the middle to the distal third of the forearm (as seen in this case), or those with significant displacement has been associated with ulnar nerve injury [5]. Mechanisms such as direct contusion from the displaced fracture or persistent direct pressure from an unreduced fracture are responsible for nerve injury at the time of fracture [11]. In our reported case, ulnar nerve palsy occurred due to entrapment within fracture fragments as shown in (Fig. 3a).

Complete neurological assessment on the first presentation is very important to diagnose the type of nerve injury and to decide about the plan of care. Treatment can vary from conservative observation of the neuropraxia to nerve exploration and repair for nerve transection or laceration. Stavrakakis et al. [12] recommended nerve exploration for post manipulation nerve palsy, worsening nerve injuries, and those not showing any improvement after 20 weeks of injury. Anatomical fracture fixation is essential for favorable functional outcome after the injury [8]. Similar to our study, Hirasawa et al. [13] showed in their study that complete neurological recovery was achieved at 4 months’ post-surgery. Dalhin et al. [6] concluded that a meticulous neurological examination should be made in all forearm fractures in adults and in children pre-operatively and post-operatively. M Zain-ur-Rehman et al. [7] said that it is important to evaluate the patient neurologically before any procedure or manipulation and manage same according to the type of lesion. The injured nerve should be explored at the time of open repositioning and plating of the fracture.

We feel that there is a tendency to look only at the x-rays of the fractured limb and miss complete neurological examination at the time of initial presentation. Also in pediatric population, patients may not be able to tell about sensory loss and motor deficit. Missing neurological injury at initial assessment likely has chances of long-term sequelae [4].

Ulnar nerve injury associated with close both bone forearm fracture is uncommon. When the nerve is injured, it is usually a contusion injury for which the treatment is conservative. Immediate nerve exploration and fracture fixation should be performed upon suspicion of nerve laceration or entrapment with displaced fracture fragments on radiographs. This prevents delay and also avoids nerve sequelae to occur. Hence, it is important to have a high index of suspicion to recognize and diagnose the type of nerve lesion early with thorough neurological assessment to decide upon the plan of management and get optimum results.

Early complete neurological examination in a patient with both bone forearm fracture is very important to prevent missing the rare ulnar nerve injury.

References

- 1.1. Jones K, Weiner DS. The management of forearm fractures in children: A plea for conservatism. J Pediatr Orthop 1999;19:811-5. [Google Scholar]

- 2.2. Torpey BM, Pess GM, Kircher MT, Faierman E, Absatz MG. Case report: Ulnar nerve laceration in a closed both bone forearm fracture. J Orthop Trauma 1996;10:131-4. [Google Scholar]

- 3.3. Neiman R, Maiocco B, Deeney VF. Ulnar nerve injury after closed forearm fractures in children. J Pediatr Orthop 1998;18:683-5. [Google Scholar]

- 4.4. Bell CJ, Viswanathan S, Dass S, Donald G. The incidence of neurologic injury in paediatric forearm fractures requiring manipulation. J Pediatr Orthop B 2010;19:294-7. [Google Scholar]

- 5.5. Federer AE, Murphy JS, Calandruccio JH, Devito DP, Kozin SH, Slappey GS, et al. Ulnar nerve injury in pediatric midshaft forearm fractures: A case series. J Orthop Trauma 2018;32:e359-65. [Google Scholar]

- 6.6. Dahlin LB, Düppe H. Injuries to the nerves associated with fractured forearms in children. Scand J Plast Reconstr Surg Hand Surg 2007;41:207-10. [Google Scholar]

- 7.7. Zain-ur-Rehman M, Butt AJ, Khan AM, AlKhalfan Y. Ulnar nerve palsy following a closed fracture of shaft of radius and ulna in a child. Int J Case Rep Orthop 2020;2:18-20. [Google Scholar]

- 8.8. Vopat ML, Kane PM, Christino MA, Truntzer J, McClure P, Katarincic J, et al. Treatment of diaphyseal forearm fractures in children. Orthop Rev (Pavia) 2014;6:5325. [Google Scholar]

- 9.9. Suganuma S, Tada K, Hayashi H, Segawa T, Tsuchiya H. Ulnar nerve palsy associated with closed midshaft forearm fractures. Orthopedics 2012;35:1680-3. [Google Scholar]

- 10.10. Clarke AC, Spencer RF. Ulnar nerve palsy following fractures of the distal radius: Clinical and anatomical studies. J Hand Surg Br 1991;16:438-40. [Google Scholar]

- 11.11. Schwartsmann CR, Ruschel PH, Huyer RG. Ulnar nerve paralysis after forearm bone fracture. Rev Bras Ortop 2016;51:475-7. [Google Scholar]

- 12.12. Stavrakakis IM, Daskalakis II, Magarakis GE, Christoforakis Z, Katsafarou MS. Ulnar nerve injuries post closed forearm fractures in paediatric population: A review of the literature. Clin Med Insights Pediatr 2019;13:117955651984187. [Google Scholar]

- 13.13. Hirasawa H, Sakai A, Toba N, Kamiuttanai M, Nakamura T, Tanaka K. Bony entrapment of ulnar nerve after closed forearm fracture: A case report. J Orthop Surg (Hong Kong) 2004;12:122-5. [Google Scholar]

- 14.14. Hamdan MQ, Haddad BI, Hawa A, Abdelhamid SS. Ulnar nerve palsy as a complication of closed both-bone forearm fracture in a pediatric patient: A case report. Int Med Case Rep J 2019;12:79-84. [Google Scholar]