Tubercular osteomyelitis of the cuboid is a rare entity which needs high degree of suspicion and medical management is sufficient for complete cure without complications.

Dr. R P Packkyarathinam, Department of Orthopaedics, Government Medical College, Omandurar Government Estate, Chennai, Tamil Nadu, India. E-mail: packkyarathinam@gmail.com

Introduction: Tuberculosis (TB) affection of foot appears to be a rare clinical entity and accounts for <10% and 0.1-0.3% of osteoarticular and extrapulmonary TB, respectively. In TB foot, tarsal joints and calcaneum are more commonly affected followed by talus, distal end of first metatarsal, navicular, cuneiforms, and cuboid bones.

Case Report: A 24-year-old female presented with pain and swelling over dorsum of the left foot from the past 8 months. On examination, there was a diffuse round shaped, solitary swelling measuring about 3.5 cm × 2.5 cm (approx.) with its surface smooth, non-pulsatile, non-fluctuant, non-transilluminant, non-compressible, and non-reducible present over dorsum of the left foot. Radiographic investigations revealed osteolytic lesion over the base of 3rd, 4th, and 5th metatarsals, middle and lateral cuneiforms and cuboid bones along with soft tissue swelling and diffuse transient osteopenia. Under spinal anesthesia, trucut biopsy of the mass revealed paucibacillary type of TB in histopathological examination. The patient was provided with ATT drugs in the form of intensive phase drugs (HRZE) daily for 4 months and continuation phase drugs (HRE) daily for 10 months according to the weight of the patient. The patient was followed up with erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein every 2 months once. The patient achieved a normal range of movements in the midtarsal joints except for the painful terminal range of movements. The patient was still under our follow-up.

Conclusion: The cuboid is the second most involved tarsal bone. The diagnosis is not always frankly evident, and a high index of suspicion has to be maintained. Surgical intervention should be limited to biopsy only as multidrug chemotherapy alone is sufficient to achieve complete healing.

Keywords: Cuboid, osteomyelitis, tuberculosis, anti-tuberculous therapy, tarsal bone.

Tuberculosis (TB) is a major health concern especially in developing countries like India which has a population of 1.39 billion, second largest in the world [1]. India has a prevalence rate of 193/100,000 population [2]. Of this, extra pulmonary TB (EPTB) constitutes 10-15% [3]. Musculoskeletal TB constitutes 1-5% of all forms of TB and 10-18% of EPTB [4, 5]. TB affection of foot appears to be a rare clinical entity and accounts for <10% and 0.1-0.3% of osteoarticular and extrapulmonary TB, respectively [6, 7]. In TB foot, tarsal joints and calcaneum are more commonly affected followed by talus, distal end of first metatarsal, navicular, cuneiforms, and cuboid bones [8]. Plenty of studies are available for pulmonary TB, but studies pertaining to EPTB especially musculoskeletal TB are scanty. In this study, we report a case of TB osteomyelitis in cuboid bone, an unusual location for musculoskeletal TB. We report this case due to its rarity, as there were only 15 reported cases of TB osteomyelitis of cuboid bone in the literature.

A 24-year-old female was presented with pain and swelling over dorsum of the left foot from the past 8 months. The pain was insidious in onset and dull aching in nature. The swelling was insidious in onset and slowly increasing in size to attain the present size. There was no history of injury, infection, sinus, or other swellings on her left foot. On examination, there was a diffuse round shaped, solitary swelling measuring about 3.5 cm × 2.5 cm (approx.) with its surface smooth, edges being indistinct, non-pulsatile, non-fluctuant, non-transilluminant, non-compressible and non-reducible present over dorsum of left foot. Muscle wasting was present. There was no arterial bruits and venous hum on auscultation. The distal neurovascular status was intact. The range of motions of left foot was painful and restricted. There was no regional lymphadenopathy.

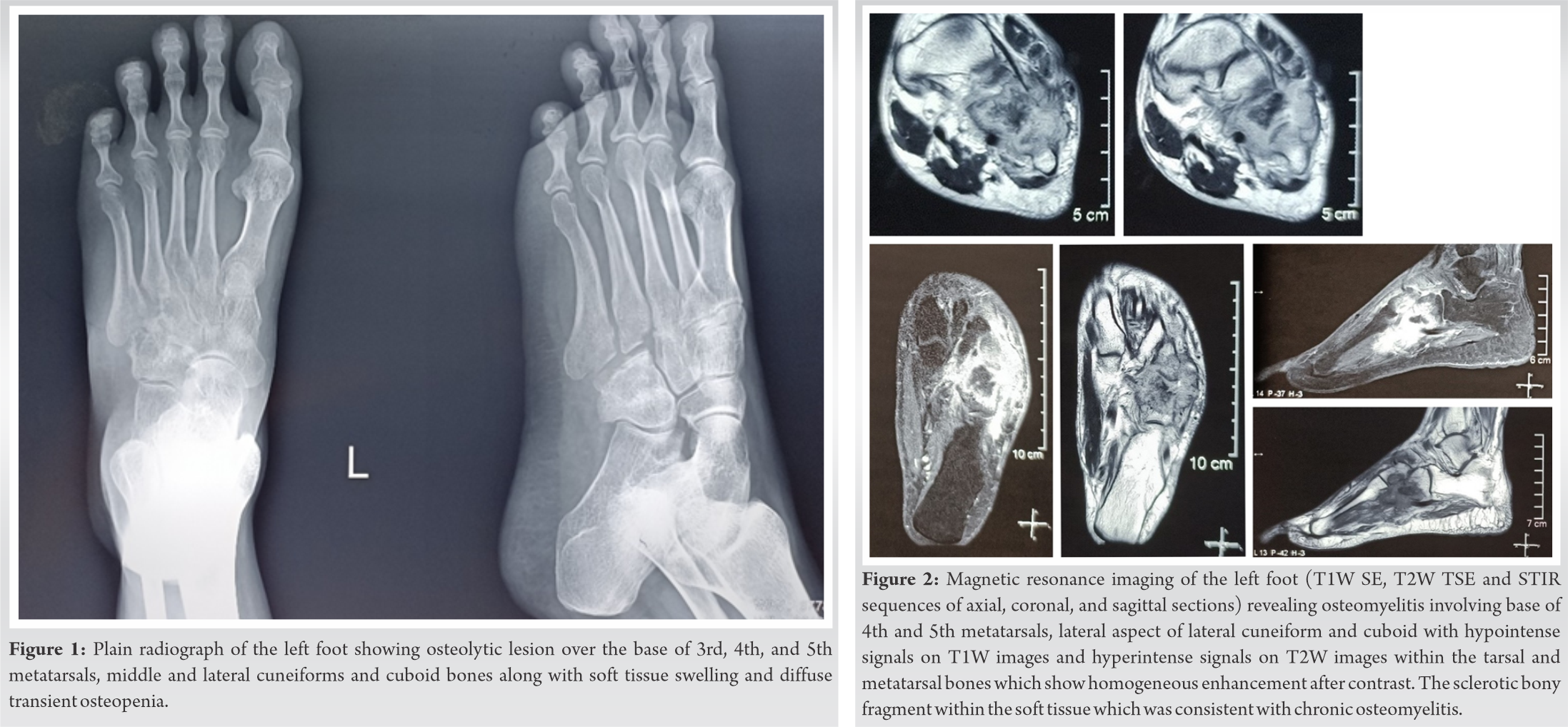

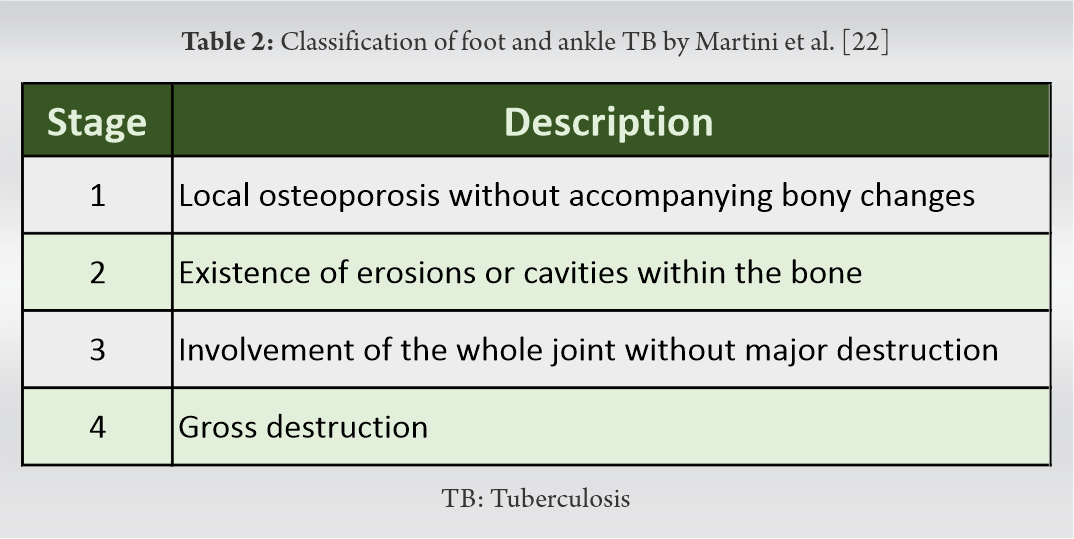

Plain radiograph of left foot revealed osteolytic lesion over the base of 3rd, 4th, and 5th metatarsals, middle and lateral cuneiforms and cuboid bones along with soft tissue swelling and diffuse transient osteopenia as shown in (Fig. 1). Magnetic resonance imaging of the left foot (T1 SE, T2 TSE and STIR sequences of sagittal, coronal and axial sections) revealed osteomyelitis involving base of 4th and 5th metatarsals, lateral aspect of lateral cuneiform and cuboid with hypointense signals on T1W images and hyperintense signals on T2W images within the tarsal and metatarsal bones which show homogeneous enhancement after contrast. Multiple erosions are seen with the evidence of joint effusion and soft tissue abscess formation on the antero-lateral aspect of the tarso-metatarsal joint. The soft tissue component also shows homogeneous enhancement with two pockets of central non-enhancing necrotic component in them. Evidence of tiny sclerotic bony fragment within the soft tissue which was consistent with chronic osteomyelitis (Fig. 2).

Under spinal anesthesia, trucut biopsy of the mass was taken along with the drainage of the pus with an uneventful postoperative period. Gene Xpert of the pus sample revealed no resistance to either isoniazid (H) or rifampicin ®. AFB staining revealed paucibacillary type of TB. Histopathology of the biopsied mass revealed lymphocytic infiltration along with caseating necrosis and with an occasional langhans giant cells scattered in between the lymphocytic infiltrates (Fig. 3). The culture of pus was attempted and found to be positive for MOTS group of mycobacteria. The patient was provided with high protein diet, Vitamin D and calcium supplementation and ATT drugs in the form of intensive phase drugs (HRZE) daily for 4 months according to the weight of the patient. The patient was followed up with erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and C-reactive protein (CRP) every 2 months once. During intensive phase, the patient experienced pain relief and decrease in the size of the swelling. The patient achieved a normal range of movements in the midtarsal joints except for the painful terminal range of movements. The continuation phase drugs (HRE) daily for 12 months have been given with ESR and CRP follow-up once in every 2 months. No recurrence of pain and swelling were reported during the continuation phase follow-up. The patient was still under our follow-up.

Musculoskeletal TB (approx. 20%) occurs as an extrapulmonary manifestation with or without pulmonary involvement and is of paucibacillary in nature [9, 10, 11]. The most common form of musculoskeletal TB occurs in spine (50-70%) (thoracic 50% > cervical 25% > lumbar 25%) followed by pelvis (12%), hip and femur (10%), knee and tibia (10%), ribs (7%), ankle/foot or shoulder (2%), elbow or wrist (2%), and multiple sites (3%) [12, 13, 14].

TB affection of foot appear to be a rare clinical entity and accounts for <10% and 0.1% to 0.3% of osteoarticular and extrapulmonary TB, respectively [6, 7]. Hindfoot TB is more common in occurrence than midfoot TB [15]. In TB foot, tarsal joints and calcaneum are more commonly affected followed by talus, distal end of first metatarsal, navicular, cuneiforms and cuboid bones [8]. Musculoskeletal TB of foot has four forms of presentation namely (1) periarticular osseo-granuloma, (2) central osseo-granuloma, (3) primary hematogenous synovitis, and (4) tenosynovitis and bursitis [16, 17].

Dhillon et al. encountered a diagnostic delay ranged from 2 months to 2 years in their TB foot and ankle series cases due to misdiagnosis of a tumor condition or acute pyogenic condition [7, 18]. Our case was diagnosed in the time span of 8 months since the onset of disease pathology. The diagnostic tests of ESR and CRP are not assisting to arrive at a conclusion since they are non-specific and increased in various disorders. Although no specific clinical or radiological modalities are available for diagnosisng TB, the relevant radiological and histopathological examination will help in diagnosing the clinical condition. Various authors have performed biopsy of the lesion and confirmed the diagnosis of TB of foot and ankle [19, 20, 21]. For more specific diagnosis, the demonstration of organism either in staining or culture must be done from the biopsy specimens.

To date, we found a total of 15 cases (11 adults and 4 pediatric cases) on tubercular osteomyelitis of cuboid were found on literature search which were tabulated (Table 1).

Treatment of foot and ankle TB were medical management if the cases were mild to moderate degree and respond to the course of ATT drugs or medical with surgical if the cases were severe degree and do not respond to conservative methods. Many surgeons preferred long-term ATT drugs for managing TB foot and ankle [6, 7, 20, 29]. For severe and non-responding cases, surgical modalities such as debridement and curettage, debridement, sequestrectomy, bone grafting, fistulectomy, synovectomy, arthrodesis, and resection [18, 30, 31]. The reported literature shows very low or no recurrence of TB foot and ankle disease pattern in the follow-up period [19].

Our case of TB cuboid and associated tarsal and metatarsals belong to the variety of periarticular osseo-granuloma of TB foot. According to Martini et al classification, our patient had the presence of erosions and cavities within base of 3rd, 4th, and 5th metatarsals, middle and lateral cuneiforms, and cuboid bones of left foot. During 14th month of follow-up, the radiograph of the left foot shows consolidation of the lesion in the cuboid (Fig. 4).

Due to rarity of foot and ankle TB, the published results show the limited long-term results. Biopsy and histopathological evaluation and culture and staining of the organism from the lesion remain the most standard diagnostic modality in the cases of suspected osseous TB. Long-term administration of ATT drugs with or without surgical intervention prevents the residual deformity associated with osseous TB.

Tuberculosis should be considered in the differential diagnosis for any unexplained lesions in the endemic regions and medical management gives successful outcome on histopathological confirmation of the lesion.

References

- 1.Huddart S, Singh M, Jha N, Benedetti A, Pai M. Case fatality and recurrent tuberculosis among patients managed in the private sector: A cohort study in Patna, India. PLoS One 2021;16:e0249225. [Google Scholar]

- 2.TBFacts TB Statistics, India. TBFacts; 2020. Available from: https://tbfacts.org/tb-statistics-india [Last accessed on 2021 Oct 20]. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee JY. Diagnosis and treatment of extrapulmonary tuberculosis. Tuberc Respir Dis 2015;78:47-55. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Leonard MK, Blumberg HM. Musculoskeletal tuberculosis. Microbiol Spectr 2017;5:1128. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gambhir S, Ravina M, Rangan K, Dixit M, Barai S, Bomanji J. Imaging in extrapulmonary tuberculosis. Int J Infect Dis 2017;56:237-47. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dhillon MS, Singh P, Sharma R, Gill SS, Nagi ON. Tuberculous osteomyelitis of the cuboid: A report of four cases. J Foot Ankle Surg 2000;39:329-35. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dhillon MS, Nagi ON. Tuberculosis of the foot and ankle. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2002;398:107-13. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vijay V, Sud A, Mehtani A. Multifocal bilateral metatarsal tuberculosis: A rare presentation. J Foot Ankle Surg 2015;54:112-5. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Procopie I, Popescu EL, Huplea V, Pleșea RM, Ghelase SM, Stoica GA, et al. Osteoraticular tuberculosis-brief review of clinical morphological and therapeutic profiles. Curr Health Sci J 2017;43:171-90. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Piccini P, Chiappini E, Tortoli E, de Martino M, Galli L. Clinical peculiarities of tuberculosis. BMC Infect Dis 2014;14:S4. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen ST, Zhao LP, Dong WJ, Gu YT, Li YX, Dong LL, et al. The clinical features and bacteriological characterizations of bone and joint tuberculosis in China. Sci Rep 2015;5:11084. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Talbot J, Bismil Q, Saralaya D, Newton D, Frizzel R, Shaw D. Musculoskeletal tuberculosis in Bradford a 6-year review. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 2007;89:405-9. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Watts HG, Lifeso RM. Current concepts review tuberculosis of bones and joints. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1996;78:288-99. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang L, Wang J, Feng X, Tao Y, Yang J, Zhang S, et al. Multifocal skeletal tuberculosis: A case report. Exp Ther Med 2016;11:1288-92. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dhillon MS, Sharma S, Gill SS, Nagi ON. Tuberculosis of bones and joints of the foot: an analysis of 22 cases. Foot Ankle 1993;14:505-13. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Natsis K, Grammatikopoulou D, Kokkinos P, Fouka E, Totlis T. Isolated tuberculous arthritis of the ankle: A case report and review of the literature. Hippokratia 2017;21:97-100. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gursu S, Yildirim T, Ucpinar H, Sofu H, Camurcu Y, Sahin V, et al. Long-term follow-up results of foot and ankle tuberculosis in Turkey. J Foot Ankle Surg 2014;53:557-61. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dhillon MS, Aggarwal S, Prabhakar S, Bachhal V. Tuberculosis of the foot: An osteolytic variety. Indian J Orthop 2012;46:206-11. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mittal R, Gupta V, Rastogi S. Tuberculosis of the foot. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1999;81:997-1000. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Muratori F, Pezzillo F, Nizegorodcew T, Fantoni M, Visconti E, Maccauro G. Tubercular osteomyelitis of the second metatarsal: A case report. J Foot Ankle Surg 2011;50:577-9. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jain VK, Kumar D, Arya RK, Sinha S, Naik AK. Tubercular osteomyelitis of the first metatarsal bone as a cause of forefoot pain. Foot Edinb Scotl 2016;27:19-21. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Martini M, Benkeddache Y, Medjani Y, Gottesman H. Tuberculosis of the upper limb joints. Int Orthop 1986;10:17-23. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Miron D, El AL, Zuker M, Lumelsky D, Murph M, Floyd MM, et al. Mycobacterium fortuitum osteomyelitis of the cuboid after nail puncture wound. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2000;19:483-5. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Agarwal A, Qureshi NA, Khan SA, Kumar P, Samaiya S. Tuberculosis of the foot and ankle in children. J Orthop Surg Hong Kong 2011;19:213-7. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ferguson KB, Jones CE, Thomson AG, Moir JS. A rare case of tuberculosis of the midfoot. Foot Ankle Spec 2012;5:327-9. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Upadhaya GK, Jain VK, Sinha S, Naik AK. Isolated calcaneocuboid joint tuberculosis: A rare case report. Foot (Edinb) 2013;23:169-71. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jeyaseelan L, Williams D, Tibrewal S, Ali SA, Hassan M, Vemulapalli K. Tuberculosis of the cuboid: A case report and review of the literature. J Foot Ankle Surg 2015;54:713-6. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vijay V, Vaishya R. Isolated C-C joint tuberculosis a diagnostic dilemma. Foot (Edinb) 2015;25:182-6. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Baveja CP, Gumma VN, Jain M, Jha H. Foot ulcer caused by multidrug-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis in a diabetic patient. J Med Microbiol 2010;59 Pt 10:1247-9. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rasool MN. Osseous manifestations of tuberculosis in children. J Pediatr Orthop 2001;21:749-55. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gavaskar AS, Chowdary N. Tibiotalocalcaneal arthrodesis using a supracondylar femoral nail for advanced tuberculous arthritis of the ankle. J Orthop Surg Hong Kong 2009;17:321-4. [Google Scholar]