We report the first case of a patient with COVID-19 infection who developed inflammatory aseptic arthropathy; this case demonstrates the importance of remaining vigilant about the new and unique manners, in which COVID-19 may present itself.

Dr. Akhil Sharma, Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, St. Luke’s University Health Network, 801 Ostrum Street, Bethlehem, PA 18015, USA. E-mail: akhilsharma93@gmail.com

Introduction: COVID-19 is among the most deleterious pandemics that the world has ever faced. It is known that SARS-CoV-2 engenders its effects by triggering a massive immune response identified as a “cytokine storm,” but the full extent of clinical manifestations of the disease is still not understood.

Case Presentation:We report the first case of a patient with COVID-19 infection who developed inflammatory (IL) aseptic arthropathy. The patient is a South Asian male of Indian origin residing in the United States.

Conclusion: This case demonstrates the importance of remaining vigilant about the new and unique manners, in which COVID-19 may present itself. Providers should be aware of the possible development of IL arthropathy in patients with the disease.

Keywords: COVID-19, inflammatory arthropathy, aseptic arthropathy, musculoskeletal sequelae.

The coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) disease has cemented its place among the most deleterious pandemics that the world has ever faced. Its prevalence has not shown signs of decline and is currently at 750,000 new cases each day globally, while over 280 million people have already been infected around the world [1]. It causes significant mortality, particularly among those with medical comorbidities [2]. While we know initial presentation of COVID-19 which includes fever, cough, dyspnea, myalgia, headache, and diarrhea, suspicion of infectivity must remain high given reports of asymptomatic disease [3]. Advanced stages often manifest as respiratory failure and acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) [3, 4, 5]. Immunologically, SARS-CoV-2 engenders effects by triggering massive immune response identified as a “cytokine storm” [6, 7, 8]. Although it remains unclear which cytokine is most critical, scientists have determined that inflammatory (IL-1), IL-6, tumor necrosis factor (TNF), and granulocyte/macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) play instrumental roles [8, 9]. The primary target is epithelial cells, especially those expressing angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2). Endocytosis of the virus by ACE2-containing epithelial cells of the mouth, tongue, upper airways, and alveolar type 2 (AT2) cells ultimately lead to alveolar damage characteristic of COVID-19 [4]. There is very little literature on activity of ACE2 in connective tissue; however, a recent study has proposed that IL-6 secreted from chondrocytes might affect ACE2 expression in synovial tissues from patients with osteoarthritis [10]. Therefore, it is possible that ACE2 may be upregulated in active synovium of patients with IL arthritis and may play a similar role in synovial destruction. A connection has also been established between SARS-CoV-2 and rheumatoid arthritis (RA) [10, 11]. Endemic human coronavirus, parainfluenza, and metapneumovirus have been linked to an increased rate of RA development [12]. Many of the same cytokine agents mediating the pathology of RA overlap with the effector cytokines induced by SARS-CoV-2 [12, 13]. Some researchers have proposed that anti-rheumatic drugs used in management of RA may successfully treat COVID-19 by addressing the systemic acute-phase response driving hyper-IL states seen in both diseases [4]. Unlike hepatitis B or C, parvovirus, and rubella, coronaviruses do not cause self-limited or chronic bouts of arthritis [5, 6]. COVID-19 patients often present with non-specific and mild musculoskeletal symptoms, which can look similar to those from other respiratory viruses. In this report, we aim to describe the association between SARS-CoV-2 and IL aseptic arthropathy that have not been reported previously. By better understanding how COVID-19 affects joint spaces, we can better elucidate diagnostic and treatment algorithms for identifying and managing this virus.

This is a 68-year-old male from New Jersey who immigrated from South Asia 41 years ago, who works as a small business owner. His medical history before hospital admission in March was significant for lifestyle-controlled diabetes mellitus (admission HbA1c of 6), hyperlipidemia (previously on Atorvastatin), and L4-L5 radiculopathy. One month before admission, he underwent uncomplicated decompressive laminectomy for his herniation. He has not had other surgeries. Home medications include 81 mg Aspirin. He is a non-smoker, who does not abuse alcohol or drugs, and his BMI was 24.2 on admission. His symptoms first began on March 23, with non-specific complaints of fatigue, dyspnea, cough, chills, and fever (Tmax 101oF). His symptoms progressed over 3 days and he developed frank hematuria at home on March 26, prompting a visit to the emergency room. There, he was found to be hypoxic (SpO2 high 80s), febrile, and tested positive for COVID-19. Hematuria was attributed to acute kidney injury (AKI) and self-resolved. On admission, the patient was started on 200 mg twice daily hydroxychloroquine and 500 mg twice daily azithromycin. On day 2, he developed progressive dyspnea and hypoxia despite non-invasive ventilatory support with high-flow nasal cannula. He was urgently intubated in the setting of severe hypotension with blood pressures documented as low as 60/40. Central access was gained through common femoral artery and he was transitioned to the intensive care unit.

On March 28, the patient’s clinical course worsened with increasing pressure requirements, persistent fevers (Tmax 103.5oF), and hypotension. His symptoms were concerning for cytokine storm and he was given a single 400 mg dose of IL-6 inhibitor, Tocilizumab. He stabilized hemodynamically and remained on pressure-support before self-extubation on April 1. He was placed on supplemental oxygen through high-flow nasal cannula, which was eventually weaned to room air. On April 9, he was discharged to inpatient rehabilitation following a negative COVID-19 test result. Several days after admission to the rehabilitation center, routine lower extremity Doppler found asymptomatic deep venous thrombosis in the patient’s common femoral vein. He was subsequently transitioned from prophylactic heparin to therapeutic Enoxaparin sodium. On April 20, he developed acute pain in the right knee while practicing stairs with physical therapy. He had limited range of motion and ultimately could not bear weight. His knee was swollen and painful. Ultrasound found a 7 cm suprapatellar joint effusion in the setting of low-grade fever (100.8oF) and a warm, and erythematous knee. He was transferred back to the emergency room for evaluation, where he underwent knee arthrocentesis. Orthopedic surgery was consulted for possible septic arthritis; 80cc of synovial fluid was drained with mild improvement in pain.

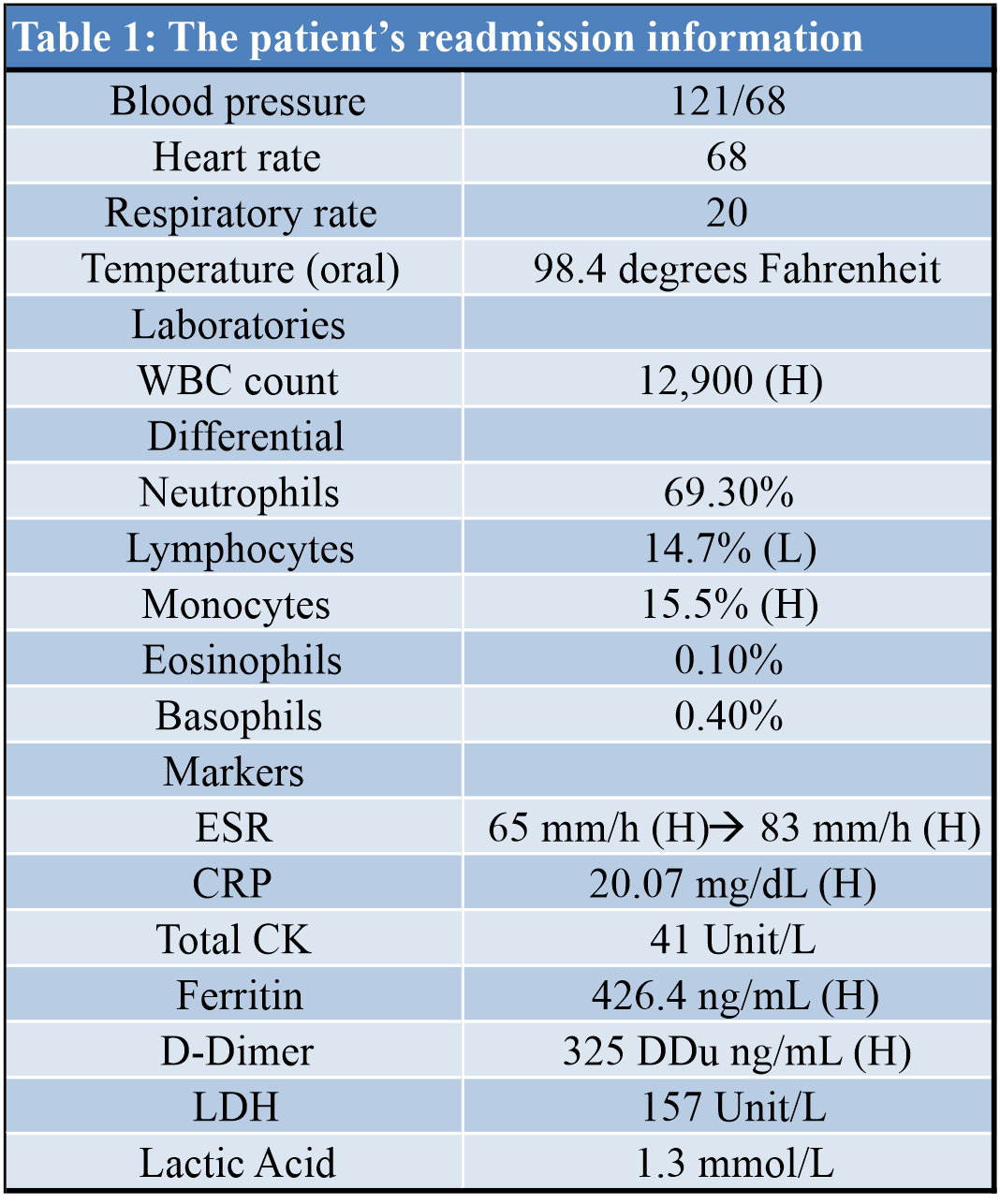

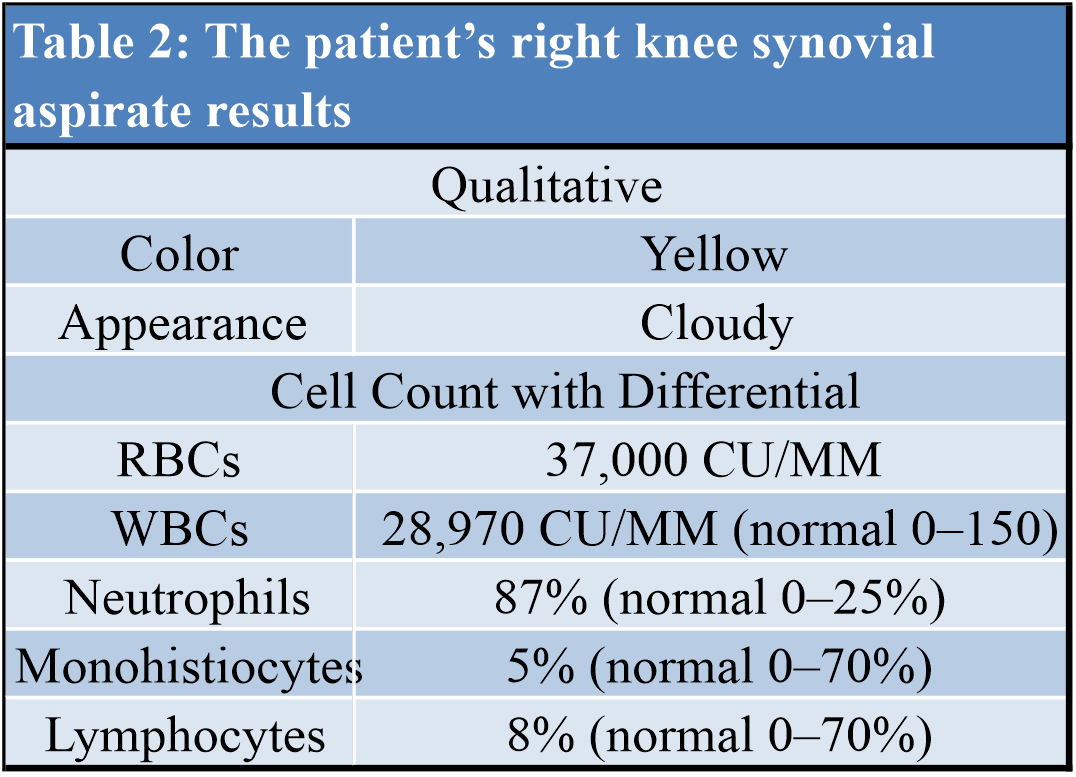

The patient was admitted back to the hospital on April 23, and his vitals consisted of blood pressure of 121/68, heart rate of 68 beats/min, respiration rate of 20 respirations/min, and temperature of 98.4oF. He was immediately started on empiric antibiotics (Vancomycin 1 g IV twice daily and Zosyn 3.375 g every 6 h) while awaiting laboratory testing of synovial fluid. Readmission laboratories revealed high white blood cell count, with high lymphocytes and low monocytes. IL markers were elevated as well. Microscopic review of the aspirate showed cloudy yellow synovial fluid with neutrophilic predominance of 87% (normal 0–25%), but did not reveal any crystals, and bacterial culture showed no growth to date times 5 days. A full workup of the patient’s readmission laboratories and aspirate is listed in (Tables 1, 2). He was transitioned from intravenous antibiotics to oral cephalexin 500 mg every 6 h for 9 days (to complete a 14 day course) and started on a 5-day Prednisone taper given suspicion for IL aseptic arthropathy in the setting of COVID-19. He was transferred back to inpatient rehabilitation for weakness and poor endurance secondary to hospitalization for severe illness. He was ultimately transitioned from therapeutic Enoxaparin sodium to oral Apixaban 5mg twice daily and discharged home on May 12.

Understanding the clinical spectrum of COVID-19 will allow physicians to better identify, isolate, and treat patients. Our report aims to share the scenario, in which IL aseptic arthropathy developed in the setting of COVID-19 infection. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first such reported case, and pathogenesis of this orthopedic complication may provide further information regarding the clinical course of this novel coronavirus. Myalgia, arthralgia, and severe fatigue are seen early and often over the course of this disease [2, 3, 4, 5]. However, not much else is known about the way this virus affects the bones and joints, including the pathway by which it mediates effects on the musculoskeletal system [13]. Its association with RA has prompted clinicians to consider repurposing existing drugs used to treat RA as potential remedies for COVID-19 [13, 14]. However, to date, there are no studies reporting the link between COVID-19 and other inflammatory arthropathies. Herein, we present a case, in which a patient developed inflammatory aseptic arthropathy following hospital admission for severe respiratory distress secondary to COVID-19 infection. Initial concern was for septic arthritis given prolonged hospitalization; however, the patient only met two criteria for septic arthritis (joint pain and swelling, and mild fever of Tmax 100.8oF). There were no other signs of systemic illness at the time of his joint effusion, and he had since tested negative for COVID-19. Cultures from serum and synovial fluid were negative for bacterial growth. Given the aspirate was clear and non-hemorrhagic, hemarthrosis secondary to trauma or coagulopathy was also excluded from the differential diagnoses. Ultimately, the managing team of clinicians concluded that the patient had developed an inflammatory aseptic arthropathy in his right knee.

We propose the patient’s development of arthropathy that is related to the “cytokine storm” that causes damage to various organs in the body. Through excessive activation of cytokines such as TNF, IL-1, GM-CSF, IL-17, IL-6, IL-1, IL-8, and MCP1, this virus is linked to development of ARDS, multi-organ failure, and death [4, 15]. The hyper-inflammatory state may have additionally contributed to our patient’s development of ARDS and the incidental DVT at the rehabilitation center, given reports on hypercoagulability of SARS-CoV-2 through thromboinflammation from viral infection, originating in the pulmonary vasculature [15].

Thus, the inflammatory storm may influence both acute and subacute clinical courses of patients with COVID-19. Clinical features of COVID-19 that is characteristic of other diseases have also been reported elsewhere [10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15]. Thus, it is imperative that we remain vigilant in our clinical suspicion and diagnostic workup of various clinical symptoms/complaints. Further investigation with retrospective review may provide additional insight into the incidence and prevalence of pro-inflammatory conditions such as aseptic arthropathy in the setting of COVID-19.

This case demonstrates the importance of remaining vigilant about the new and unique manners in which COVID-19 may present itself. Providers should be aware of the possible development of inflammatory arthropathy in patients with the disease.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Situation Reports. Available from: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel148 coronavirus-2019/situation-reports [Last accessed on 2020 Aug 04]. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jose RJ, Manuel A. COVID-19 cytokine storm: The interplay between inflammation and coagulation. Lancet Respir Med 2020;8:e46-7. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jiang F, Deng L, Zhang L, Cai Y, Cheung CW, Xia Z. Review of the clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). J Gen Intern Med 2020;35:1545-9. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schett G, Manger B, Simon D. COVID-19 revisiting inflammatory pathways of arthritis. Nat Rev Rheumatol 2020;16:465-70. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li X, Ma X. Acute respiratory failure in COVID-19: Is it “typical” ARDS? Crit Care 2020;24:198. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schett G, Sticherling M, Neurath MF. COVID-19: Risk for cytokine targeting in chronic inflammatory diseases? Nat Rev Immunol 2020;20:271-2. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sarzi-Puttini P, Giorgi V, Sirotti S, Marotto D, Ardizzone S, Rizzardini G, Antinori S, Galli M. COVID-19, cytokines and immunosuppression: What can we learn from severe acute respiratory syndrome? Clin Exp Rheumatol 2020;38:337-42. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Henderson LA, Canna SW, Schulert GS, Volpi S, Lee PY, Kernan KF, et al. On the alert for cytokine storm: Immunopathology in COVID-19. Arthritis Rheumatol 2020;72:1059-63. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Channappanavar R, Perlman S. Pathogenic human coronavirus infections: Causes and consequences of cytokine storm and immunopathology. Semin Immunopathol 2017;39:529-39. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ragab D, Eldin HS, Taeimah M, Khattab R, Salem R. The COVID-19 cytokine storm; what we know so far. Front Immunol 2020;11:1446. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Abou-Ismail MY, Diamond A, Kapoor S, Arafah Y, Nayak L. The hypercoagulable state in COVID-19: Incidence, pathophysiology, and management. Thromb Res 2020;194:101-15. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Esper F, Shapiro ED, Weibel C, Ferguson D, Landry ML, Kahn JS. Association between a novel human coronavirus and Kawasaki disease. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2005;24:395-6. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alizargar J. The novel coronavirus (COVID-19) and the risk of Kawasaki disease in children. J Formos Med Assoc 2020;119:1713-4. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Viner RM, Whittaker E. Kawasaki-like disease: Emerging complication during the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet 2020;395:1741-3. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hirano T, Murakami M. COVID-19: A new virus, but a familiar receptor and cytokine release syndrome. Immunity 2020;52:731-3. [Google Scholar]