In front of a volar dislocation of the lunate, the authors stress the importance of carefully assessing lesions and searching for any associated injuries both clinically and radiologically.

Dr. Jean G. Louka, Department of Orthopaedics and Traumatology, Simone Veil Hospital, 14 Rue de Saint Prix, Eaubonne, France. E-mail: jeanloukas@gmail.com

Introduction:Lunate dislocation is a rare and devastating injury of the wrist that requires prompt management and surgical repair. The association of this lesion with a flexor pollicis longus (FPL) injury and a Stener lesion appears to be extremely uncommon.

Case Report:We present the case of a 31-year-old man who was riding his motorbike when he was struck by a car, resulting in a volar dislocation of the lunate, a concomitant fracture of the second phalanx of the thumb, a FPL avulsion, and a thumb ulnar collateral ligament (UCL) injury. While there are numerous articles about associated lunate and other carpal and wrist injuries, a combination of lunate dislocation with the above-mentioned injuries is exceptionally rare. After conducting a literature review, the clinical case was detailed and discussed. The injuries were managed with open reduction, internal fixation of the lunate dislocation, primary direct repair of the scapholunate ligament and thumb UCL tears utilizing suture anchor fixation, and surgical reinsertion of the FPL tendon.

Conclusion: In the face of the atypical presentation, we stress the importance of carefully assessing the lesion and searching for any associated injuries both clinically and radiologically, particularly if a comprehensive evaluation was not possible.

Keywords:Carpal bone, lunate dislocation, thumb ulnar collateral ligament injury, Stener lesion, flexor pollicis longus avulsion.

Lunate dislocation is a rare and devastating injury of the wrist [1]. The association of this lesion with a flexor pollicis longus (FPL) injury and a Stener lesion appears to be extremely uncommon. The authors present the case of a 31-year-old man who suffered a volar dislocation of the lunate with a concomitant FPL avulsion and a thumb ulnar collateral ligament (UCL) injury. These lesions are more common in isolation, but the distinctiveness of this case is due to the combination of the lesions. There was no similar case report in the literature that we could find. The primary goal of this case report is to bring out a very unusual entity by describing the clinical and radiological findings as well as the surgical procedures performed. The patient was informed and consented to the publication of the case data.

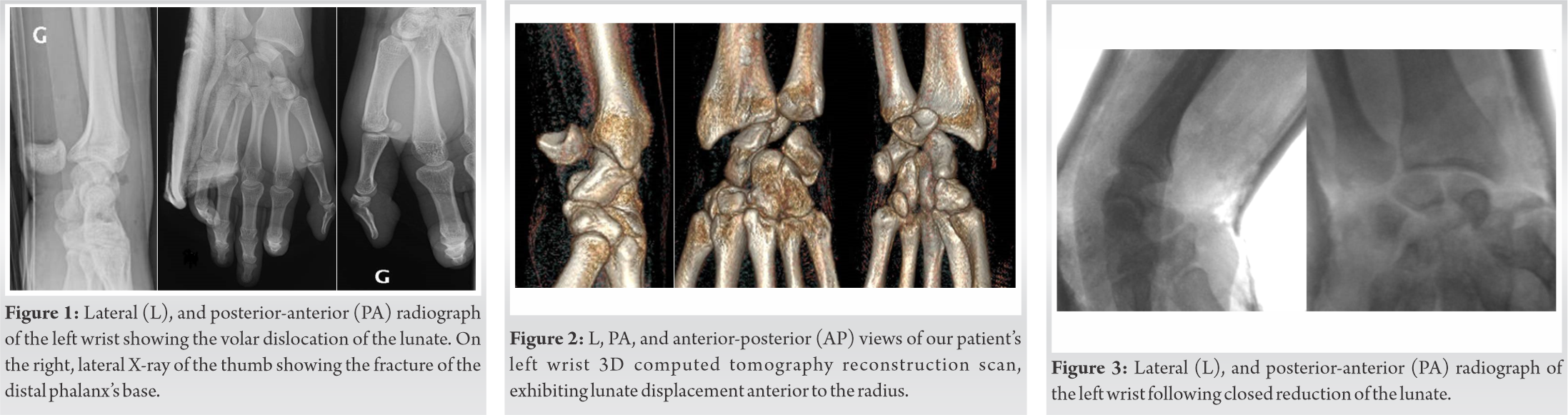

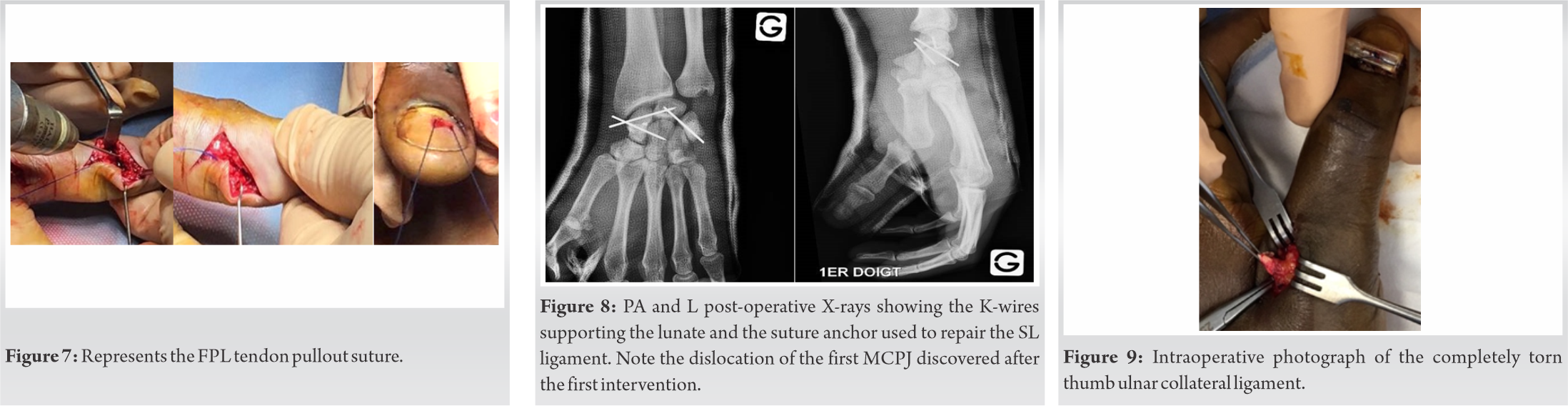

This is a case of a 31-year-old right-hand-dominant man who was riding his motorbike when he was involved in a collision with a car, where he suffered an extremely severe left wrist and hand injury. The patient was previously healthy and did not take any drugs regularly. Clinical examination, which was limited due to severe pain, revealed swelling and deformity of the palmar aspect of the wrist, significantly limited wrist range of motion, and deformity of the left thumb. Standard radiographs and a computed tomography scan of the hand and wrist with 3D reconstruction showed an acute volar dislocation of the lunate (Mayfield IV) with the rest of the carpus intact, along with a concomitant extra-articular fracture of the base of the second phalanx of the thumb (Fig. 1, 2).

On presentation, our patient was brought into the operation suite for emergency reduction under fluoroscopic control. The lunate dislocation was preliminarily reduced by external maneuvers: Wrist extension and traction, along with pushing the lunate back into its anatomic position by applying direct thumb pressure over it from volar to dorsal. The achieved reduction was extremely unstable and the lunate demonstrated a dorsal intercalated segment instability deformity, necessitating surgical treatment (Fig. 3). The wrist was subsequently immobilized in a plaster splint in a 10° palmar flexion position, while the thumb fracture was reduced and immobilized in extension.

The patient was operated on 72 h after the accident under regional anesthesia, with a pneumatic tourniquet applied after administration of intravenous antibiotics. The upper limb was prepped and draped in the standard sterile fashion. Our reconstruction was approached first by a dorsal approach to the lunate. Dissection was carried down to the level of the carpal bones. The posttraumatic hematoma was removed and the surgical site was irrigated. When we explored the incision, we saw a tendon, lying curled up in the diastasis of the scapholunate (SL) complex, which we did not recognize at first (Fig. 4). After ensuring that the extensor tendons were intact. We assessed the flexors, and based on its length and caliber, we concluded that the tendon, we encountered, was the FPL lacerated in zone I. The distal end of the FPL was retrieved by a palmar incision at the wrist (Fig. 5). Returning to the dorsal incision, the dorsal SL ligament was identified as a big stump that had avulsed from the scaphoid and remained attached to the lunate. Initially, the lunate was reduced in its anatomical position and, then, stabilized with three Kirschner wires (K-wires) across the SL, scaphocapitate, and lunotriquetral intervals. Following debridement of the scaphoid area, where the ligament was avulsed, one DePuy Mitek MicroFix® QuickAnchor® Plus (3/0 Suture) was inserted. The anchor sutures were placed and secured into the torn end of the ligament. After stabilizing the lunate, we opened the carpal tunnel and recovered the FPL tendon from beneath the median nerve. The tendon was then passed through the intact thumb pulleys (Fig. 6). A pullout suture was necessary on the 2nd phalanx to repair the tendon securely (Fig. 7). The wrist was immobilized with a plaster cast in a neutral position.

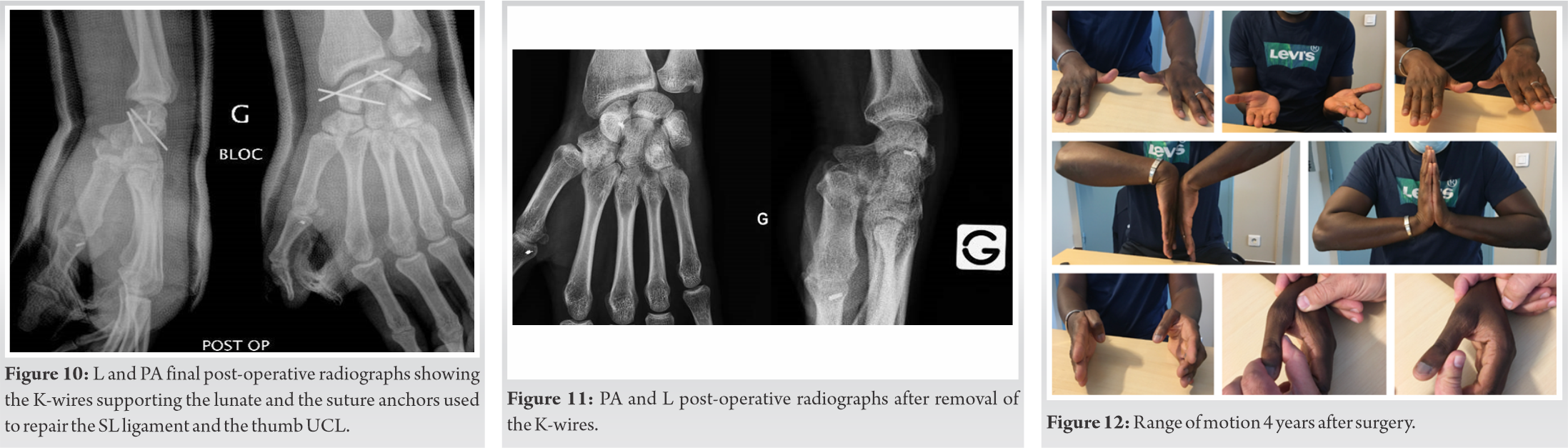

Postoperatively, plain film X-rays revealed metacarpal–phalangeal joint (MCPJ) instability of the thumb (Fig. 8). Two days after the first procedure, our patient was operated on again under general anesthesia. Stress testing was performed in 30° of flexion with a soft endpoint and >35° of MCPJ deviation, indicating a complete rupture of the UCL. The UCL was repaired using a dorsoulnar approach to the first MCPJ. A complete Stener’s lesion was identified (Fig. 9). After copious irrigation, a DePuy Mitek MicroFix® QuickAnchor® Plus (3/0 Suture) was inserted in the anatomical footprint of the UCL, the threads of which were used to reinsert the capsuloligamentous plane on the base of the 1st phalanx. The wrist and thumb were immobilized in a neutral position by a thumb spica plaster cast in for 7 weeks. The post-operative period was uneventful and the radiological follow-up was adequate (Fig. 10). While there are numerous publications about the association of lunate dislocation with other carpal and wrist injuries, a combination of lunate dislocation with a FPL injury and a Stener lesion is extremely uncommon.

Our patient returned to the clinic after 7 weeks to assess the healing of the SL ligament repair and UCL repair. Following the removal of the cast, the three K-wires were removed in the operating theatre. Post-operative control X-rays (Fig. 11) showed a good position of the carpal bones and the 1st MCPJ, after which the patient participated in an intense physical therapy protocol including range of motion and grip strength exercises. Six months after surgery, the patient’s wrist and thumb were found to have adequate strength and a pain-free range of motion. He denied any sense of instability and, as a result has returned to his job as a bus driver and to his sports activities.

At his final visit to the clinic, 4 years after the accident, our patient was very satisfied, as he had fully recovered and the range of motion was as follows in comparison to the contralateral side: Active wrist extension 80°/85°, flexion 65°/75°, stable valgus stress testing of the first MCPJ, and complete forearm pronation-supination range. When compared to the contralateral hand, grip strength (measured with a Jamar dynamometer) averaged 90 lbs./110 lbs., while pinch strength (measured with a Pinch dynamometer) averaged 15 lbs./25 lbs. (Fig. 12).

A Stener lesion arises when the aponeurosis of the adductor pollicis muscle is caught between the MCPJ and torn ligament due to a complete distal thumb UCL rupture. It happens when the first MCPJ is forced into abduction and hyperextension, causing the distal UCL to avulse from its insertion at the base of the proximal phalanx of the thumb. The ligament’s severed end becomes tangled in the adductor aponeurosis, preventing it from returning to its normal anatomical position. This causes an unstable thumb, that is common among skiers and gamekeepers [2]. The thumb’s UCL is made up of the proper collateral ligament and the accessory collateral ligament and its main function is to provide ulnar stability to the MCP joint and to act as a counterbalance to any force directed radially during a vigorous grasp [3]. Stener lesions are seen in between 64 and 87% of all complete UCL ruptures [4]. Besides, lunate dislocation is a rare injury that mainly affects young adults after high-energy trauma that involves forceful loading of the dorsiflexed and ulnarly deviated wrist, such as falling on an outstretched hand, contact sports, or motor vehicle accidents [5]. According to Mayfield et al. [6], volar lunate dislocation is the fourth and last stage of perilunate injury and the most common type of lunate dislocation, accounting for 10 to 25% of all carpal dislocations [2], [4], [5]. Contrarily, dorsal lunate dislocation is an exceedingly unusual injury, with just a few cases in the literature, predominantly occurring with other carpal bones or distal radius fractures [6], [7]. When discussing carpal injury, it is crucial to remember that the wrist is a complex joint composed of the radius, ulna, and eight carpal bones organized into two rows: The proximal row and the distal row [10]. During daily tasks, it is subjected to a complex degree of mobility. The lunate is located between the scaphoid and triquetrum and is connected to both via the scapholunate and lunotriquetral (LT) interosseous ligaments. The lunate is kept balanced between opposing forces by these two large intercarpal attachments. When the SL or LT ligaments are injured, the stability is lost, and the lunate is dominated by the remaining intercarpal relationship [10]. The damage of the SL ligament releases the scaphoid moving it into flexion. The lunate then extends unrestrictedly following the triquetrum. The damage of the LT ligament decreases the SL angle, because the lunate loses its extension effect from the triquetrum. Interestingly, lunate dislocation follows a sequence of events starting with the rupture of the SL ligament, followed by the disruption of the capitolunate articulation, the LT articulation, and the failure of the dorsal radiocarpal ligament, respectively [11].

Patients may suffer symptoms such as pain, limited joint range of motion, and acute carpel tunnel syndrome [12]. The key to restoring wrist mobility and pain relief is accurate diagnosis and treatment of these injuries. The missed diagnosis was observed in up to 25% of cases in a multicenter study by Herzberg et al. [8]. Thorough clinical and radiological evaluations play a key role in assessing lunate dislocations, which frequently go unreported in the emergency room, leading to long-term disability and pain [10]. The typical radiological findings on a lateral wrist X-ray include the dislocation of the lunate from the lunate fossa, commonly volar into the space of Poirier, also called the “spilled teacup” sign, with loss of collinearity of the radius, lunate, and capitate [13] as well as an abnormal SL angle of >70° or <30° [10]. An anteroposterior (AP) X-ray of the wrist can show the lunate overlapping the capitate and having a triangular appearance, also known as the “piece of pie” sign [13], as well as the disruption of the Gilula’s arcs [14]. These arcs can be viewed in the normal AP view of the wrist [10]. The scaphoid, lunate, and triquetral bones’ proximal surfaces are outlined in arc I while their distal surfaces are outlined in arc II. Arc III defines the capitate’s and hamate’s proximal surfaces [12], [13]. Patients with unreduced dislocations can present months or even years after the trauma even if they have adequate hand function and minimal pain [16].

Closed reduction is achievable most of the time but challenging to maintain. Consequently, the outcomes are unpredictable and the treatment of choice is an open reduction with ligament repair and carpus stabilization [17]. There are a variety of surgical techniques used for the repair of lunate dislocations. One of the most used techniques is open reduction internal fixation (ORIF) with ligament repair using dorsal, volar, or combined approaches. ORIF starts with the reduction of lunate then fixation using Kirschner wires. K-wires can be utilized as joysticks to align the carpus. After that, K-wires are inserted into the scaphoid and lunate to close the SL diastasis. The SL ligament can then be repaired acutely using suture anchors. Although LT interosseous ligament can be repaired using similar techniques, there is insufficient evidence to support this additional step [18]. According to the literature, there is no superiority in results when comparing dorsal versus volar approaches [18]. However, in most cases, surgeons use the dorsal approach initially so as not to hinder a possible persistent anterior lunate vascularization, to gain greater access to the carpus, restore alignment, and repair the SL interosseous ligament, which is considered the most critical factor in achieving long-term successful results [19]. The volar approach may be preferred for direct palmar capsule repair, and when there are symptoms of median nerve compression and carpal tunnel release is indicated [17]. Ultimately, it is worth noting that the lunate’s volar displacement and rotation can compress the median nerve within the carpal tunnel, which is a rare cause of median nerve entrapment neuropathy [15]. Despite early repair, many patients with lunate dislocations have poor long-term sequelae, including degenerative arthritis, scapholunate advanced collapse (SLAC), loss of grip strength, median nerve irritation, and persistent wrist instability [20]. The patient’s risk of having long-term complications can be minimized by utilizing ORIF and ligamentous repair in a timely manner. Additional surgical correction is frequently required to manage these complications [21]. In the end, lunate dislocation follows a reproducible pattern; to achieve the best results, early reduction and surgical repair are critical.

Lunate dislocations are infrequent but serious wrist injuries that can occur in a variety of ways. In the face of the atypical presentation, we stress the importance of carefully assessing the lesion and searching for any associated injuries both clinically and radiologically, particularly if a comprehensive evaluation was not possible. Nevertheless, to maximize patient satisfaction and function, anatomic repair of bony and ligamentous injuries should be perfectly achieved.

This is a rare case of a 31-year-old man who suffered a volar dislocation of the lunate with a concomitant FPL avulsion and a thumb UCL injury. The authors stress the importance of carefully assessing lesions and searching for any associated injuries both clinically and radiologically, particularly if a comprehensive evaluation was not possible.

References

- 1.Grabow RJ, Catalano L. Carpal dislocations. Hand Clin 2006;22:485-500. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lucerna A, Rehman UH. Stener Lesion. 2021 Nov 22. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2022 Jan–. PMID: 31082048. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hung CY, Varacallo M, Chang KV. Gamekeepers Thumb. 2022 Feb 12. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2022 Jan–. PMID: 29763146. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mahajan M, Rhemrev SJ. Rupture of the ulnar collateral ligament of the thumb – A review. Int J Emerg Med 2013;6:1. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kaewlai R, Avery LL, Asrani AV, Abujudeh HH, Sacknoff R, Novelline RA. Multidetector CT of carpal injuries: Anatomy, fractures, and fracture-dislocations. Radiographics 2008;28:1771-84. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mayfield JK, Johnson RP, Kilcoyne RK. Carpal dislocations: Pathomechanics and progressive perilunar instability. J Hand Surg Am 1980;5:226-41. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nypaver C, Liu S. Perilunate injuries/lunate dislocations and radiocarpal dislocations. Ann Jt 2021;636. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Herzberg G, Comtet JJ, Linscheid RL, Amadio PC, Cooney WP, Stalder J. Perilunate dislocations and fracture-dislocations: A multicenter study. J Hand Surg Am 1993;18:768-79. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zaidenberg EE, Roitman P, Gallucci GL, Boretto JG, De Carli P. Foreign-body reaction and osteolysis in dorsal lunate dislocation repair with bioabsorbable suture anchor. Hand (N Y) 2016;11:368-71. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tucker A, Marley W, Ruiz A, Tucker A. Radiological signs of a true lunate dislocation. BMJ Case Rep 2013;2013:2-3. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wingelaar M, Newbury P, Adams NS, Livingston AJ. Lunate dislocation and basic wrist kinematics. Eplasty 2016;16:ic37. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Matthewson G, Larrivee S, Clark T. Case report of an acute complex perilunate fracture dislocation treated with a three-corner fusion. Case Rep Orthop 2018;2018:1-5. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Scalcione LR, Gimber LH, Ho AM, Johnston SS, Sheppard JE, Taljanovic MS. Spectrum of carpal dislocations and fracture-dislocations: Imaging and management. Am J Roentgenol 2014;203:541-50. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Peh WC, Gilula LA. Normal disruption of carpal arcs. J Hand Surg Am 1996;21:561-6. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bhatia M, Sharma A, Ravikumar R, Maurya VK. Lunate dislocation causing median nerve entrapment. Med J Armed Forces India. 2017 Jan;73(1):88-90. doi: 10.1016/j.mjafi.2015.12.006. Epub 2016 Mar 29. PMID: 28123252; PMCID: PMC5221394. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nagle DJ. Evaluation of chronic wrist pain. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 2000;8:45-55. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dumontier C, Zu Reckendorf GM, Sautet A, Lenoble E, Saffar P, Allieu Y. Radiocarpal dislocations: Classification and proposal for treatment – A review of twenty-seven cases. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2001;83:212-8. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pappas ND, Lee DH. Perilunate injuries. Am J Orthop (Belle Mead NJ) 2015;44:E300-2. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Najarian R, Nourbakhsh A, Capo J, Tan V. Perilunate injuries. Hand 2011;6:1-7. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Budoff JE. Treatment of acute lunate and perilunate dislocations. J Hand Surg Am 2008;33:1424-32. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kiefhaber TR. Management of scapholunate advanced collapse pattern of degenerative arthritis of the wrist. J Hand Surg Am 2009;34:1527-30. [Google Scholar]