Open subtotal synovectomy in knee tuberculosis, as a surgical management, is a prudent and effective alternative to augment the chemotherapy for early symptomatic relief caused by mechanical and evident decrease in the disease load.

Dr. Kartik Prashant Pande, 300 Resident Hostel, JJ Hospital Campus,JJ Hospital, Byculla, Mumbai. Maharashtra. India. E-mail: kartik.pande0393@gmail.com

Introduction:Skeletal tuberculosis (TB) accounts for approximately 10–35% of the extra-pulmonary cases, where knee TB accounts for around 8% of extra-pulmonary TB cases after hip and spine. In about one-third of patients with extra-pulmonary TB, pulmonary TB is concomitantly found. The management of knee TB poses an initial diagnostic challenge due to its non-specific symptoms and absence of constitutional symptoms after which depending on the response to AKT – surgical intervention open or arthroscopic could be contemplated.

Case Report:We have a 30-year-old female patient diagnosed with the right-sided knee TB on synovial biopsy started on anti-tubercular treatment. After 1 month of conservative middle path regimen, She presented to us with worsening knee pain and swelling over the right knee and difficulty in standing and moving out of bed as well as inability to sleep and night cries affecting significantly her activities of daily living. The patient was managed with open arthrotomy and subtotal synovectomy was done along with thorough debridement resulting in significant reduction in the pain and swelling in the post-operative period with return of range of motion with daily activities.

Conclusion:As clear in our case, apart from the conventional chemotherapeutic regimen for TB, surgical management is sometimes indicated in patients with an aggressive joint infection with severe impairment in performing activities of daily living. It also helps to decrease the disease load which provides symptomatic relief to the patient and helps in recovery, thereby improving the quality of life.

Keywords:Synovial biopsy, activities of daily living, arthrotomy, synovectomy, debridement, middle path regimen, night cries.

Although the majority of the newly diagnosed cases of TB are pulmonary, skeletal TB accounts for approximately 10–35% of the extra-pulmonary cases [1]. Knee TB accounts for around 8% of extra-pulmonary TB cases after hip and spine [2]. In about one-third of patients with extra-pulmonary TB, pulmonary TB is concomitantly found. Osteoarticular TB poses a diagnostic challenge to many clinicians including pulmonologists and orthopedists, in that, they present at a quite later stages when most of the joint destruction processes have ensued. In earlier stages, the culture and gene xpert reports might come negative delaying the diagnosis even further [3]. The diagnosis of skeletal TB is most often narrowed down due to a high degree of suspicion augmented by preliminary X-rays showing no obvious bony abnormality, more so in developing countries like India where TB is endemic and non-traumatic joint swelling with should include tuberculosis (TB) as a possible diagnosis before contemplating other diagnoses such as tumors [4]. The management of mono-articular TB depends on multiple factors taking the host and organism specific factors into consideration, consisting of both medical and surgical treatment as and when required. TB of the knee joint causing synovitis initially, most often is of hematogenous and lymphatic origin due to dissemination of the mycobacterium bacilli. Tuberculous knee synovitis is a rare entity but potentially lethal if left untreated, it can progress to the advanced stage of severe arthritis causing gross deformity and ankyloses of the joint with the possible complications of disseminated TB. Hence, prompt diagnosis with an effective management plan along with aggressive surgical intervention, whenever required in the form of synovectomy, debridement should not be withheld until it is too late for it to have destroyed the joint causing fibrosis, cartilage destruction, and ultimately functional knee immobility [5].

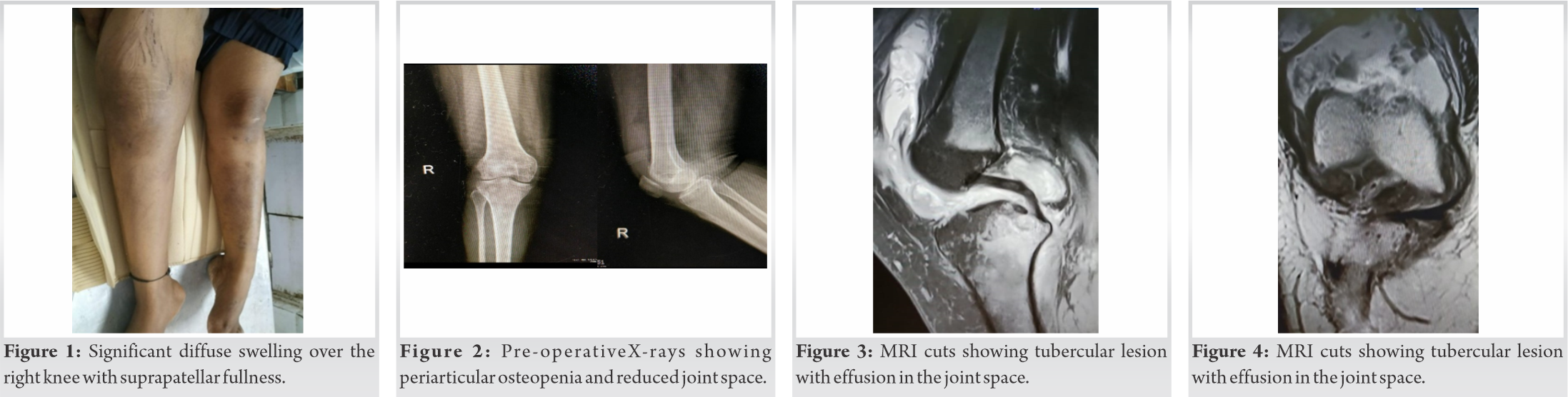

We have a 30-year-old female patient who came with pain and swelling over the right knee for 1 year. The swelling was non-traumatic, insidious in onset, and gradually progressive. It was associated with dull aching pain, diffuse in nature, gradually progressive in intensity, increased on activity, and relieved on rest and medication. The patient had no constitutional symptoms of fever, weight loss, and evening rise of temperature, cough, breathlessness, chest pain, or any h/o contact with a confirmed case of TB. The patient had presented to us 6 months after her complaints. On examination, there was diffuse swelling over the right knee (Fig. 1) with fullness in the supra-patellar area, along with local rise of temperature and diffuse tenderness over the knee. Chest radiograph was normal. On preliminary imaging with X-ray of the right knee– a mild periarticular osteopenia along with supra-patellar joint effusion was noted with no other bony abnormality (Fig. 2). Subsequently, MRI was advised for further evaluation which showed inflammatory/infectious arthritis and synovitis (Fig. 3-5) which needed further evaluation with a histopathological examination of the tissue. After performing a USG-guided synovial biopsy, in which a granulomatous inflammation of probable mycobacterial etiology was found following which she was started on First Line Category-1 Anti-tubercular drugs (AKT).

The patient presented to us 1 month after starting AKT with complaints of severe pain and swelling aggravated over the past month affecting and unable to do her activities of daily living such as walking, squatting, sitting cross legged (those activities requiring flexion of the knee). Clinical examination at this time suggested that synovial hypertrophy was significant. Patient was in severe pain and spasm. Not allowing to flex beyond 30° for further clinical evaluation. Rest pain and night cries were present. An open arthrotomy was planned for the patient to reduce the aggressive disease load and rule out drug resistant TB or any missed diagnosis by histopathological diagnosis from all deeper corners of the knee.

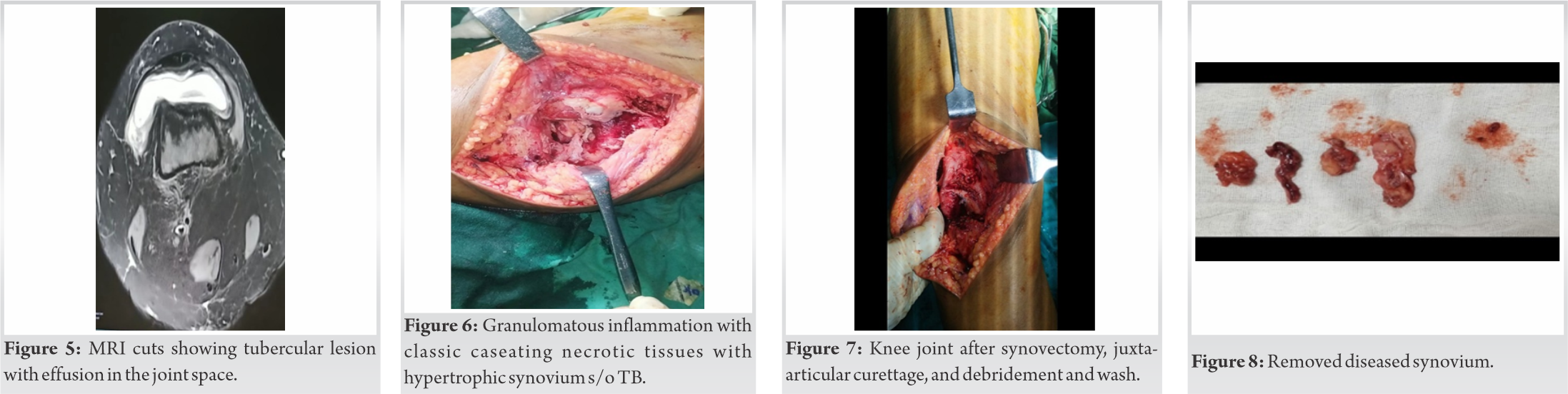

The patient was placed in a supine position over the operating table and induced under all aseptic precautions with spinal and epidural anesthesia. Scrubbing, panting, and draping were done. With anterior approach, a midline incision of about 15 cm extending from just proximal to the superior pole of patella up to the tibial tuberosity with the knee in 90°flexion was taken. Skin and subcutaneous tissue incised and flaps raised on both sides with quadriceps tendon, patella, and patellar tendon in the center. A medial parapatellar incision was taken keeping a sleeve of 2 cm from patellar margins leaving buttress for suturing back later. Patella was subluxated laterally to expose the joint. All imaging and HPE findings were confirmed intraoperatively where a typical cheesy white caseating granulomatous tissues with a hypertrophied synovium and a diseased articular cartilage were found (Fig. 6). A subtotal synovectomy was done by excising the hypertrophied synovium from suprapatellar pouch, medial and lateral gutter, and intercondylar notch. The rice bodies removed from the gutters by thorough joint lavage. All possible diseased synovium from anterior, lateral, and medial side was removed along with removal of the destroyed cartilage over the joint (Fig. 7). A thorough washwith copious amount of normal saline with curettage of juxta-articular bone lesions was done. The exposed cartilage was drilled to stimulate fibrocartilage growth over cartilage defects. Extensor retinaculum was sutured properly after achieving hemostasis. Closure was done in layers over negative suction drain. Sterile dressing was given with compression bandage. In the immediate post-operative period, the patient was stable and was shifted to the ward. The excised synovium (Fig. 8) was sent for gene xpert examination, a repeat histopathological examination, and TB-MGIT culture. Histopathological report was suggestive of granulomatous inflammation with caseating necrosis s/o TB. Post-operative wound check dress was done on 3rd day where no induration was seen. The patient was kept on a skin traction over a simple pulley with 3kg weight to reduce joint pain and spasm as well as to prevent eroded cartilage over the joint surface from coming in contact. Patient was mobilized with partial weight bearing from post-operative day (POD)-2. She experienced significant reduction in pain, in particular the night cries, and swelling from POD-3. Physiotherapy was started with active assisted and passive knee ROM exercises taught to the patient from the POD-3. AKT was continued as per regimen. Suture removal was done on POD-14, with no wound complication (Fig. 9). The patient attained knee flexion of up to 90° by POD-14 (Fig. 10) and was discharged on follow-up.

TB is an ancient disease, with evidence of it affecting humans from as long as 5000 years ago. Cut to the 20th century, with the advent of anti-tubercular drugs, mortality and morbidity due to TB decreased substantially along with improvement in the quality of life in patients suffering from TB. Although Mycobacterium tuberculosis is known to affect primarily the lungs, it is also known to cause skeletal TB, more so in patients who are immune-compromised for example – patients with HIV/AIDS orthose on long standing steroid treatment for some other ailment. It predominantly affects the weight bearing joints in the axial skeleton, that is, the spine, hip, and knee in decreasing order of incidence [6]. Osteoarticular TB usually presents without constitutional symptoms, which delays the diagnosis subsequently causing a delay in the treatment and, hence, significant joint destruction might ensue by this time, warranting a surgical intervention – open or arthroscopic [7, 8, 9]. A high index of suspicion, augmented by diagnostic tests including USG, MRI of the affected joint along with procedures such as synovial biopsy – CT- or USG-guided with histopathological examination of the synovium can confirm the diagnosis following which a patient appropriate treatment plan can be charted out [10]. Once the diagnosis is confirmed, options for the treatment include both medical and surgical. Medical management with anti-tubercular drugs is initially started with the surgical intervention reserved for cases with severe and aggressive disease who are affected with severe symptoms such as pain, swelling to an extent of restricting daily activities, and subsequent reduction in the quality of life. A chronic monoarticular TB should respond well to chemotherapy with few exceptions mentioned above. Chemotherapy for bone and joint TB is usually a lengthier process requiring around 12–18 months of the treatment. Surgical options include debride, synovectomy, and severe cases will require functional arthrodesis and rarely amputation of the affected limb. Joint arthroplasty remains a viable option in an appropriate patient [11]. As our patient was already a diagnosed case of knee TB on biopsy started on chemotherapy regimen, surgical intervention in this case was primarily indicated for significant reduction in the disease load so as to facilitate the AKT to act on a less severe form of the disease giving early improved joint condition thereby improve the quality of life. One of the reasons of the excruciating pain that the patient was experiencing can be attributed to the aggressive nature of the mycobacterium, causing havoc at the knee joint – capsule infiltration along with cartilage destruction, once these processes have ensued, exposing the nerve endings, the patient has immense pain at minimal joint movement. Mycobacterium-induced T-lymphocyte inflammatory damage to the joint tissues including the cartilage and synovium along with capsule giving rise to pain and other symptoms such as swelling due to effusion and subsequent restriction in the range of motion. Hence, a precise and possibly extensive surgical plan has to be deployed to alleviate the patient’s symptoms, improve the quality of life, and decrease the disease load for the chemotherapeutic drugs to act. Hence, a subtotal synovectomy was planned where the diseased hypertrophied synovium was removed from the more accessible anterior, medial, and lateral side along with removal of the diseasedand pathological cartilage. The rationale behind such aggressive approach remains majorly focused on the fact the removal of diseased tissue and debridement will stimulate neoangiogenesis in the local area and aid in better healing of the joint in addition to the added advantage of increased delivery of anti-tubercular drugs to the site. Neoangiogenesis will also aid in effectively removing the inflammatory debris from the area which will further hasten the process of cartilage healing. Drilling the fibrocartilage also augments our efforts of obtaining a healed articular cartilage across the joint. Following this, there was clinical improvement as experienced by the patient in the form of return of assisted knee ROM, reduction of pain, and swelling. The patient will be kept on regular 4 weekly follow-up with continuation of AKT for another 12–18 months.

As clear in our case, apart from the conventional chemotherapeutic regimen for TB, surgical management is sometimes indicated in patients with an aggressive joint infection with severe impairment in performing activities of daily living. It also helps to decrease the disease load which provides symptomatic relief to the patient and helps in recovery, thereby improving the quality of life.

We recommend subtotal synovectomy for a severe aggressive form of knee TB with increased pain, swelling, and severe restriction in range of motion of the joint to avoid dreaded complications of end-stage arthritis at a young age such as this.

References

- 1.Peto HM, Pratt RH, Harrington TA, LoBue PA, Armstrong LR. Epidemiology of extrapulmonary tuberculosis in the United States, 1993-2006. Clin Infect Dis 2009;49:1350-7. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dhillon MS, Nagi ON. Tuberculosis of the foot and ankle. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2002;398:107-13. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mkandawire NC, Kaunda E. Bone and joint TB at queen Elizabeth central hospital 1986 to 2002. Trop Doct 2005;35:14-6. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Opondo E. Diagnosis and the surgical management of hip and knee Mycobacterium tuberculous arthritis. Surg Res 2019;1:1-6. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ciobanu LD, Pesut DP. Tuberculous synovitis of the knee in a 65-year-old man. Vojnosanit Pregl 2009;66:1019-22. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Malaviya AN, Kotwal PP. Arthritis associated with tuberculosis. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 2003;17:319-43. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Furia JP, Box GG, Lintner DM. Tuberculous arthritis of the knee presenting as a meniscal tear. Am J Orthop (Belle Mead NJ) 1996;25:138-42. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Abdulaziz S, Almoallim H, Ibrahim A,Samannodi M, Shabrawishi M, Meeralam Y, et al. Poncet’s disease (reactive arthritis associated with tuberculosis): Retrospective case series and review of literature. Clin Rheumatol 2012;31:1521-8. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Netval M, Hudec T, Hach J. Our experience with total knee arthroplasty following tuberculous arthritis (1980-2005). Acta Chir Orthop Traumatol Cech 2007;74:111-3. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Adler CP. Bone Diseases: Macroscopic, Histological and Radiological Diagnosis of Structural Changes in the Skeleton.Berlin, Germany: Springer; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Leclere LE, Sechriest VF, Holley KG,Tsukayama DT. Tuberculous arthritis of the knee treated with two-stage total knee arthroplasty. A case report. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2009;91:186-91. [Google Scholar]