To avoid overlooking bilateral foraminal stenosis, it is important to be familiar with its imaging and clinical presentation.

Dr. Kohei Takahashi, Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, Tohoku University School of Medicine, Seiryo-Machi, Aoba-Ku, Sendai, Japan. E-mail: kohei.takahashi.c1@tohoku.ac.jp

Introduction: The classical symptom of foraminal stenosis is unilateral radiculopathy. Bilateral radiculopathy caused purely by foraminal stenosis is rare. Here, we report five cases of bilateral L5 radiculopathy caused purely by L5–S1 foraminal stenosis and describe the clinical and radiological features of these patients in detail.

Case Presentation: Among the five patients, two were men and three were women with an average age of 69 years. Four patients had undergone surgeries at L4–5 level, previously. All the patients showed an improvement in symptoms in the post-operative period. After a certain period, the patients complained of bilateral leg pain and numbness. An additional surgery was performed in two patients; however, there was no improvement in symptoms. One patient, who did not undergo surgery, was treated conservatively for 3 years. All the patients had been suffering from bilateral leg symptoms before their first visit to our hospital. The neurological findings in these patients were consistent with bilateral L5 radiculopathy. The average pre-operative Japanese Orthopedic Association (JOA) score was 13 out of 29 points. Bilateral foraminal stenosis at L5–S1 level was confirmed using a three-dimensional magnetic resonance imaging or computed tomography. Posterior lumbar interbody fusion was performed in one patient and bilateral lateral fenestration using Wiltse’s approach was performed in four patients. The neurological symptoms recovered immediately after surgery. The average JOA score at 2-year follow-up was 25 points.

Conclusions: Spine surgeons may overlook the pathology of foraminal stenosis, particularly in patients with bilateral radiculopathy. Familiarity with the clinical and radiological features of symptomatic lumbar foraminal stenosis is necessary to properly diagnose bilateral foraminal stenosis at L5–S1 level.

Keywords: Bilateral, foraminal stenosis, L5–S1.

Lumbar spinal stenosis occurs either in the spinal canal or inside and outside of the intervertebral foramen. Stenosis of the intervertebral foramen is called a foraminal stenosis [1]. The compression of neural tissues in the spinal canal often causes unilateral or bilateral radiculopathy, with or without cauda equina syndrome. The classical symptom of foraminal stenosis is unilateral radiculopathy [2]. Approximately 75% of lumbar foraminal stenosis is detected at L5-S1 level [3] due to the specific anatomical features of lumbosacral transition, such as the wider facet joints [4], higher nerve root occupancy relative to the intervertebral foramen [3], and the large transverse process fusing to the sacral ala [5]. The most frequent level of spinal canal stenosis is L4-5 [6]. Both foraminal stenosis stenosis at L5-S1 and canal stenosis at L4-5 can cause L5 radiculopathy. L5 radiculopathy does not demonstrate an abnormal deep tendon reflex in neurological examination. Moreover, foraminal stenosis is occasionally not confirmed using an ordinal two-dimensional magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) (2D MRIMRI) [7]. Based on these epidemiological, neurological, and radiological backgrounds, spine surgeons may overlook the pathology of foraminal stenosis, particularly in patients with bilateral radiculopathy. In this paper, we report five cases of bilateral L5 radiculopathy caused purely by L5-S1 foraminal stenosis that were left undiagnosed for long periods before visiting our clinic. The clinical and radiological features of these patients are described in detail in this report followed by a discussion of the reasons for delayed diagnosis and the methods to diagnose the pathology. All patients were informed of the anonymous publication of their data and informed consents have been taken from them.

Patients and clinical history

We retrospectively reviewed 1,774 lumbar surgical cases in our hospital in the last four 4 years and identified five cases of bilateral lumbar radiculopathy caused purely by foraminal stenosis. The corresponding spinal level was L5-S1 in all the cases. A summary of patients is presented in (Table 1). Two patients were men and three were women; the average age at the initial visit to our hospital was 69 years. Four patients had undergone previous lumbar surgery at L-5 level: two patients with posterior lumbar interbody fusion (PLIF) and one patient each with posterior spinal fusion (PLF) and bilateral partial laminotomy (fenestration) [8]. All the patients showed improvement in symptoms post-operatively. After a certain period, they complained of bilateral leg pain and numbness with a time gap in the onset between the sides. The interval between the initial surgery to recurrence were 3 months to 10 years. An additional surgery was performed in two patients; however, there was no improvement in symptoms. One patient, who did not undergo surgery, was treated conservatively for 3 years. The patients had been suffering from bilateral leg pain and numbness that were left undiagnosed for 9 months to 9 years before their first visit to our hospital.

Symptoms and neurological findings

All the patients presented with pain and numbness in the lateral aspect of the legs. Four patients exhibited intermittent claudication with a walking distance of 20–500 m. Four patients had difficulty sleeping because of the leg pain at rest, and all patients had leg pain while sitting. Neurologically, all patients showed sensory disturbance in bilateral L5 dermatome and grade four muscle weaknesses in the extensor hallucis longus and extensor digitorum longus. Bilateral Achilles tendon reflexes were decreased in three patients. These findings were consistent with those of bilateral L5 radiculopathy. The average pre-operative Japanese Orthopaedic Association (JOA) score was 13 out of 29 points.

Radiological findings

Plain lateral radiographs showed disc disk space narrowing and a vacuum phenomenon at L5-S1 level in all patients. Nerve root impingement in the spinal canal was not observed at any intervertebral disc disk level either on MRI or myelograms. Using a 2D MRI, foraminal stenosis at L5-S1 level was detected unilaterally in one patient and was not detected on either side in one patient. A three-dimensional MRI successfully detected bilateral foraminal stenosis at L5-S1 level in these two patients. In three patients with pedicle screws inserted into the L5 vertebral body, evaluation of foraminal stenosis using MRI was difficult due to the artifacts of the implants (Fig. 1); however, narrowing of the foramen was confirmed by computed tomography (CT). Selective radiculograms (SRG), followed by a CT scan was performed in one patient, and nerve root impingement was confirmed.

Surgical treatment

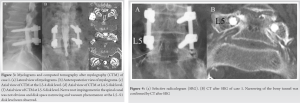

Bilateral lateral fenestration [9] using Wiltse ’s approach was performed in four patients. The bony resection at the pars interarticularis was performed as wide as the L5-S1 disc disk level was identified; however, it remained intact more than the medial half of the facet joints. The caudal portion of the L5 transverse process and sacral ala were was resected to release the up-down stenosis and the anterior-posterior stenosis, respectively. A discectomy or herniotomy was performed, when the nerve root was strained due to disc disk bulging or herniation. (Fig. 2) illustrates the area of bone resection. Consequently, the nerve root was decompressed from the intra- to the extra-foraminal zone. PLIF at L5-S1 level was performed in one patient since bilateral facetectomy was required for adequate decompression due to the previous L5 laminectomy.

Post-operative course

The Neurological neurological symptoms recovered immediately after surgery. Intermittent claudication, leg pain at rest, and leg pain while sitting disappeared in all the cases. No radiological instability was noted in any patients at the 2 -year follow-up. The average JOA scores at 2-year follow- up was 25 points.

Representative case (Case 1)

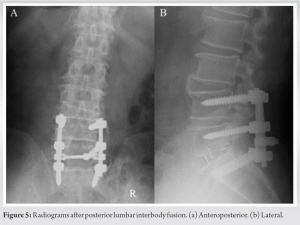

A 75-year-old man presented with bilateral leg pain and numbness, visited our hospital. He had undergone L5 laminectomy and PLF at L4-5 level one 1 year prior to before his first visit to our hospital, and his symptoms disappeared. He was symptom-free for 3 months after surgery; however, his right leg pain and numbness recurred, followed by symptoms in the left leg. An appropriate diagnosis was not made for 9 months until he visited our hospital. Manual muscle testing revealed muscle weaknesses in four out of five in the extensor hallucis longus and extensor digitorum longus. The bilateral Achilles tendon reflexes were decreased. The pinprick sensory test revealed sensory disturbances in the lateral aspect of both legs. These findings were neurologically consistent with those of bilateral L5 radiculopathy. The pre-operative JOA score was 17. In the myelograms, nerve root impingement in the spinal canal was not obvious; however, disc disk space narrowing and the vacuum phenomenon at the L5-S1 disc disk level were observed (Fig. 3). Evaluation of foraminal stenosis using MRI was difficult because of due to the presence of artifacts of the implants (Fig. 1-1a-c). Therefore, narrowing of the bilateral L5–S-1 foramen was confirmed by SRG and subsequent CT (Fig. 4). He was diagnosed with bilateral L5 radiculopathy that is caused by bilateral foraminal stenosis at L5-S1 level. PLIF at L5-S1 level was performed (Fig. 5) that resulted in the immediate improvement of symptoms. The JOA score improved to 25 at the two2-year follow-up.

Macnab (1971) reported 68 patients with lumbar radiculopathy whose pathology could not be identified by laminectomy [10]. The nerve compression was observed at the foraminal zone in more than 60% of them and he named the zone as the “hidden zone”. MRI came into practical use more than a decade after Macnab’s report and has advanced as an imaging modality [11]. Although the diagnostic utility of 2D MRI, which is most commonly used in daily practice, is limited to L5-S1 [12], 3D MRI can detect foraminal stenosis accurately [7, 12]. Nevertheless, all the patients presented here had been suffering for a long time without a correct diagnosis. There are two possible reasons for this delay in the diagnosis. First, the patients complained of bilateral leg pain and numbness. The pathology in such patients is usually considered to originate from the same intervertebral disc disk level. Thus, attention might have been focused on the intraspinal canal, where the bilateral radiculopathy often occurs at the same intervertebral disc disk level. In Additionally, three of the five patients, all of whom had previous spine surgery at L4-5, showed a decrease in the bilateral Achilles tendon reflexes that suggests bilateral S1 radiculopathy or cauda equina syndrome. This sign was probably derived from the neurological symptoms prior to before the previous surgery and may have led to an inappropriate neurological diagnosis. Second, because of due to the artifacts of the pedicle screws inserted into the L5 vertebral body, the L5 nerve root could not be identified properly, even using 3D MRI. Recent studies have demonstrated the utility of CT in the diagnosis of lumbar foraminal stenosis [13, 14]. Therefore, in cases after fusion surgery with implants, CT reconstruction is mandatory to evaluate the foraminal stenosis. Furthermore, CT after SRG that was previously used for the diagnosis of foraminal stenosis in Bertolotti syndrome [15, 16, 17, -18], could also reveal the positional relationship between the nerve root and intervertebral foramen. To focus on the foraminal zone, it is necessary to be familiar with the clinical features of symptomatic lumbar foraminal stenosis. First, pain at rest and pain while sitting with a high visual analogue scale are the characteristic symptoms of foraminal stenosis [19, 20]. In our case series, four patients had leg pain at rest and all patients had leg pain while sitting. Second, disc disk space narrowing with vacuum phenomenon at L5-S1 level is the typical radiological change of symptomatic foraminal stenosis [21, 22] that was present in all five cases. When these degenerative changes are evident in patients with lumbar radiculopathy who complain of pain at rest or pain while sitting, foraminal stenosis at the corresponding intervertebral disc disk level should be suspected, even in patients with bilateral symptoms. Orita et al. described that lumbar floating fusion surgery terminating at L5 was a significant risk factor of L5-S1 foraminal stenosis [23]. In this study, three out of the five patients had undergone single-level posterior lumbar fusion surgery at L4-5 level prior to before the onset of symptomatic bilateral foraminal stenosis. Fusion surgery with the lowest instrumented vertebra at L5 increases the stress on L5-S1 [24] that will lead to earlier degenerative changes at this spinal level. We performed bilateral lateral fenestration in four cases, and consequently, none of them developed instability at two 2- years follow-up. A randomized controlled trial comparing decompression alone with decompression and instrumented fusion also found no significant differences in the surgical outcomes [25]. Therefore, decompression alone may be the treatment of choice for lumbar foraminal stenosis as long as a sufficient amount of the facet joint could be retained.

Spine surgeons may overlook the pathology of foraminal stenosis, particularly in patients with bilateral radiculopathies. Familiarity with the clinical and radiological features of symptomatic lumbar foraminal stenosis is necessary to properly diagnose bilateral foraminal stenosis at L5-S1 level.

The reasons for difficulty in diagnosis of bilateral radiculopathy due to foraminal stenosis and tips to properly diagnose it are clearly described in this report.

References

- 1.Verbiest H. Chapter 16. Neurogenic intermittent claudication in cases with absolute and relative stenosis of the lumbar vertebral canal (ASLC and RSLC), in cases with narrow lumbar intervertebral foramina, and in cases with both entities. Clin Neurosurg 1973;20:204-14. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Porter RW, Hibbert C, Evans C. The natural history of root entrapment syndrome. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1984;9:418-21. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jenis LG, An HS. Spine update. Lumbar foraminal stenosis. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2000;25:389-94. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mahato NK. Facet dimensions, orientation, and symmetry at L5-S1 junction in lumbosacral transitional States. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2011;36:E569-73. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wiltse LL, Guyer RD, Spencer CW, Glenn WV, Porter IS. Alar transverse process impingement of the L5 spinal nerve: The far-out syndrome. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1984;9:31-41. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ishimoto Y, Yoshimura N, Muraki S, Yamada H, Nagata K, Hashizume H, et al. Associations between radiographic lumbar spinal stenosis and clinical symptoms in the general population: The Wakayama spine study. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2013;21:783-8. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nemoto O, Fujikawa A, Tachibana A. Three-dimensional fast imaging employing steady-state acquisition MRI and its diagnostic value for lumbar foraminal stenosis. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol 2014;24 Suppl 1:S209-14. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aizawa T, Ozawa H, Kusakabe T, Tanaka Y, Sekiguchi A, Hashimoto K, et al. Reoperation rates after fenestration for lumbar spinal canal stenosis: A 20-year period survival function method analysis. Eur Spine J 2015;24:381-7. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kunogi J, Hasue M. Diagnosis and operative treatment of intraforaminal and extraforaminal nerve root compression. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1991;16:1312-20. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Macnab I. Negative disc exploration. An analysis of the causes of nerve-root involvement in sixty-eight patients. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1971;53:891-903. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sofka CM, Pavlov H. The history of clinical musculoskeletal radiology. Radiol Clin North Am 2009;47:349-56. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yamada H, Terada M, Iwasaki H, Endo T, Okada M, Nakao S, et al. Improved accuracy of diagnosis of lumbar intra and/or extra-foraminal stenosis by use of three-dimensional MR imaging: Comparison with conventional MR imaging. J Orthop Sci 2015;20:287-94. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kang WY, Ahn JM, Lee JW, Lee E, Bae YJ, Seo J, et al. Is multidetector computed tomography comparable to magnetic resonance imaging for assessment of lumbar foraminal stenosis? Acta Radiol 2017;58:197-203. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Haleem S, Malik M, Guduri V, Azzopardi C, James S, Botchu R. The Haleem-Botchu classification: A novel CT-based classification for lumbar foraminal stenosis. Eur Spine J 2021;30:865-9. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ichihara K, Taguchi T, Hashida T, Ochi Y, Murakami T, Kawai S. The treatment of far-out foraminal stenosis below a lumbosacral transitional vertebra: A report of two cases. J Spinal Disord Tech 2004;17:154-7. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kikuchi K, Abe E, Miyakoshi N, Kobayashi T, Abe T, Hongo M, et al. Anterior decompression for far-out syndrome below a transitional vertebra: A report of two cases. Spine J 2013;13:e21-5. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Miyoshi Y, Yasuhara T, Date I. Posterior decompression of far-out foraminal stenosis caused by a lumbosacral transitional vertebra--case report. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo) 2011;51:153-6. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kojo S, Takahashi K, Tsubakino T, Hashimoto K, Aizawa T, Tanaka Y. Lumbar radiculopathy due to Bertolotti’s syndrome: Alternative method to reveal the “hidden zone”-a report of two cases and review of literature. J Orthop Sci 2022;16:S0949-2658(22)00063-X. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yamada H, Oka H, Iwasaki H, Endo T, Kioka M, Ishimoto Y, et al. Development of a support tool for the clinical diagnosis of symptomatic lumbar intra-and/or extra-foraminal stenosis. J Orthop Sci 2015;20:811-7. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Eguchi Y, Suzuki M, Yamanaka H, Tamai H, Kobayashi T, Orita S, et al. Assessment of clinical symptoms in lumbar foraminal stenosis using the Japanese orthopaedic association back pain evaluation questionnaire. Korean J Spine 2017;14:1-6. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Murata Y, Kanaya K, Wada H, Wada K, Shiba M, Hatta S, et al. L5 radiculopathy due to foraminal stenosis accompanied With vacuum phenomena of the L5/S disc on radiography images in extension position. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2015;40:1831-5. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ohba T, Ebata S, Fujita K, Sato H, Devin CJ, Haro H. Characterization of symptomatic lumbar foraminal stenosis by conventional imaging. Eur Spine J 2015;24:2269-75. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Orita S, Yamagata M, Ikeda Y, Nakajima F, Aoki Y, Nakamura J, et al. Retrospective exploration of risk factors for L5 radiculopathy following lumbar floating fusion surgery. J Orthop Surg Res 2015;10:164. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hashimoto K, Aizawa T, Kanno H, Itoi E. Adjacent segment degeneration after fusion spinal surgery-a systematic review. Int Orthop 2019;43:987-93. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hallett A, Huntley JS, Gibson JN. Foraminal stenosis and single-level degenerative disc disease: A randomized controlled trial comparing decompression with decompression and instrumented fusion. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2007;32:1375-80. [Google Scholar]