Brucellar spondylodiscitis may clinically mimic spinal tuberculosis; hence, it must be considered as a differential diagnosis in a patient presenting with the lower back pain (particularly in the elderly) and signs of a chronic infection.

Dr. Padma Priya, Department of Orthopaedics, Pondicherry Institute of Medical Sciences, Ganapathichettikulam, Kalapet - 605 014, Pondicherry, India. E-mail: padma.priya537@gmail.com

Introduction: Infective spondylodiscitis refers to simultaneous inflammation of vertebrae and disc and usually occurs through hematogenous spread. The most common presentation of brucellosis is febrile illness, but it can rarely present as spondylodiscitis. Rarely, human cases of brucellosis are diagnosed and treated clinically. We describe a case of previously healthy man in his early 70s who presented with symptoms suggestive of spinal tuberculosis, then diagnosed to have brucellarspondylodiscitis.

Case Report: A 72-year-old farmer presented to our orthopedic department with a history of chronic lower back pain. Spinal tuberculosis was suspected at a medical facilitynear his residence, based on magnetic resonance imaging consistent with infective spondylodiscitis, and the patient was referred to our hospital for further management. Investigations revealed that the patient had an uncommon diagnosis of Brucellar spondylodiscitis for which he was managed accordingly.

Conclusion: Brucellar spondylodiscitis may clinically mimic spinal tuberculosis; hence, it must be considered as a differential diagnosis in a patient presenting with the lower back pain (particularly in the elderly) and signs of a chronic infection. Screening serological testing is vital in early identification and management of spinal brucellosis.

Keywords: Spondylodiscitis, brucellosis, spinal brucellosis, spinal abscess, discitis, infection.

Brucellosis is a zoonosis transmitted directly or indirectly to humans from infected animals, predominantly domesticated ruminants and swine. Its clinical features are diverse and definite indicators that confirm the diagnosis may be lacking. Thus, bacteriologic and serologic test results must usually back up the clinical diagnosis. Undulant fever with excessive night sweats, arthralgia or arthritis, and hepatosplenomegaly makes up the typical triad [1]. It is a multi-system infection that usually results in musculoskeletal involvement. Osteoarticular involvement including spondylitis, sacroiliitis, osteomyelitis, peripheral arthritis, bursitis, and tenosynovitis represents the most common complication of brucellosis affecting up to 85% of the affected patients [2]. The most common symptom of spondylodiscitis is chronic back pain; however, because it is not a distinct symptom, it often leads to a delay in diagnosis and treatment. Although rare, spinal brucellosis must remain as a differential diagnosis in a patient presenting with the lower back pain and with signs of a chronic infection. Our case report reveals an uncommon case of spinal brucellosis, including its clinical presentation, serological parameters, and management.

Clinical presentation

A 72-year-old Indian male with no known comorbidities presented with a 1 year history of back pain which was insidious in onset, gradually progressive, non-radiating in nature, and aggravated in the recent past (15 days). His back pain was located in the lower dorsal region, which was most likely mechanical in nature as it was not associated with trauma or neurological symptoms such as tingling, numbness, imbalance, bowel/bladder dysfunction, or weakness in his lower extremities. There was no history of fever with weight loss, or loss of appetite. There was no history of international travel in the recent past. His clinical picture was further complicated by a significant history of pulmonary tuberculosis 12 years ago, for which he was treated with anti-tubercular therapy (ATT), but he was non-compliant with the medications. Spinal tuberculosis was suspected at a medical facility in his hometown, based on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) findings consistent with infective spondylodiscitis; hence, the patient was empirically treated with ATT under daily observed treatment and short course regimen. No signs of clinical improvement were noted following ATT; therefore, the patient was brought to our tertiary-care hospital for further management. The patient was afebrile and hemodynamically stable. Localized tenderness was present over the D10-D12 region of the spine without any swelling. Neurological examination and reflexes were normal.

Investigation

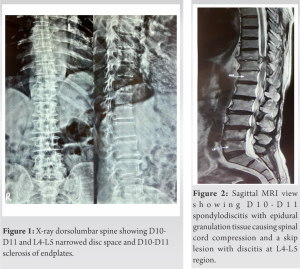

All baseline investigations were done. Hemoglobin was10.3g/dl. Total leukocyte count and differential count were within the normal range. The patient had raised erythrocyte sedimentation rate of 48mm/h and C-reactive protein of 34mg/dl. Other biochemical tests were within the normal limit. X-ray of the dorsolumbar spine showed narrowed disc space in D10-D11 and L4-L5 region and no evidence of sacroiliitis (Fig. 1). MRI of the dorsal spine revealed D10-D11 and L4-L5 infective spondylodiscitis(Fig. 2and 3). Blood culture revealed no growth of organisms in blood after 1 week of incubation in an automated blood culture system (BacT Alert). Sputum samples were negative for acid-fast bacilli (AFB).

Treatment

Prompt D10-D11 hemilaminectomy and surgical decompression produced biopsy samples and the histopathological examination of the disc tissue demonstrated dead bony trabeculae surrounded by chronic inflammatory infiltrate (Fig. 4). Granuloma was not seen. Tissue sample was negative for AFB. Mycobacterium tuberculosis was not detected by cartridge based nucleic acid amplification test. Blood sample was sent for Brucella agglutination test and the antibody titers were 1:320 for Brucella abortus and 1:80 for Brucella melitensis(ARKRAY Healthcare Pvt. Ltd, India), suggestive of brucellosis(Fig. 5). ATT was discontinued and the treatment was modified to brucellosis regime: Intravenous Gentamicin(80 mg/ml) for 3 weeks, parenteral Rifampicin(600mg) and Doxycycline(100mg) for 12 weeks each. Patient was symptomatically better at follow-up 4-week with subsidence of his pain and normalization of his inflammatory markers. Parenteral Rifampicin and Doxycycline were advised to be continued. Repeat Brucella agglutination test after 6 weeks showed significant lowering of antibody titers to 1:80 for B.

abortus.

Brucellae are small, Gram-negative, unencapsulated, non-sporulating rods, or coccobacilli. They grow aerobically on a peptone-based medium incubated at 37°C [1]. Brucella genus has been divided into six species, four of which are known to cause disease in man: B. abortus, Brucella suis, Brucella canis, and B. melitensis, the last being the foremost virulent. Human brucellosis is primarily caused by contact with occupational or domestic exposure to infected animals or their products(most commonly milk or milk products) [3]. The patient in our case worked as a farmer with a history of contact with farm animals such as cattle and pigs, which could have functioned as a vector for his infection. Identifying and eliminating the illness from its animal reservoirs are the most sensible method to regulate human brucellosis. It is endemic in areas with a higher prevalence of domesticated animals, such as the Mediterranean zone, Eastern Europe, Central Asia, Mexico, and South America [1]. India has one of the largest ruminant populations in the world and brucellosis is endemic in the country in both humans and animals [4]. Human brucellosis is traditionally described as a disease of protean manifestations and the demographic and clinical characteristics are wide with an unexpected spectrum of this disease. The incubation time varies from 1 week to several months, but is typically 2–4 weeks, with fever and other symptoms appearing suddenly or gradually [2]. It often presents in two patterns: (1) Acute brucellosis presenting with undulating fever, weight loss, and fatigue and (2) chronic brucellosis presenting years after initial exposure, characterized by osteomyelitis presenting with persistent back pain, arthralgias, and sweating [5]. Children, adults, and the elderly are more likely to develop monoarthritis (knee/hip), sacroiliitis, and spondylitis, respectively. Spondylodiscitis is said to be responsible for 6–85% of brucellar osteoarticular involvements. In the spinal area, the lumbar (60–69%), thoracic (19%), and cervical segments (6–12%) are known to be involved [6]. Mild anemia may be reported. With relative lymphocytosis, peripheral leukocyte counts are frequently normal or low. Blood culture is the gold standard approach, but sensitivity is low as most patients are treated with antibiotics before the samples are sent for blood culture. Only 53–90% of brucellosis patients have positive blood cultures [7]. Because B. abortus is rarely isolated from blood or tissue, diagnosis of the disease is based primarily on the results of serological tests. Antibody titers for Brucella have been advised for determining the prognosis of the disease. In an acute infection, immunoglobulin M (IgM) antibody appears initially, followed by immunoglobulin G (IgG) and immunoglobulin A. The total number of IgM and IgG antibodies is measured using the standard agglutination test [8]. Titer of ≥1:160 for Brucella agglutination test is considered significant as seen in the index case [9]. Tissue biopsy samples may reveal non-caseating granulomas contrasting to caseating granulomas with AFB in tuberculosis as was expected in the patient [10]. The radiological signs of osteoarticular infection appear later and are subtler than those of tuberculosis or other etiologies of septic arthritis, with less bone and joint erosion. The presence of focal erosions of the superior or inferior vertebral body angle is a common radiographic observation in this pathology. This eventually resulted in disc collapse [11]. On MRI, the lesions are seen as a destructive appearance (Pedro Pons’ sign) at the anterosuperior corner of the vertebrae with osteosclerosis, which is a pathognomonic finding. Single-focal, contiguous multifocal, or non-contiguous multifocal involvement can be seen in spondylodiscitis of an infectious etiology. The focused form is limited to the anterior region of an endplate, while the diffuse form can affect the entire vertebral body, as well as the discs, vertebrae, and epidural space [6]. Our patient likely had the non-contiguous multifocal type, involving D10-D11 intervertebral spaceand epidural space and a skip lesion in L4-L5 region. MRI plain narrowed the pathology to infective origin and excluded neoplastic lesions; hence, MRI contrast was not needed in our case. Post recovery MRI was not performed as it was not affordable by the patient. A diagnosis of spinal brucellosis is made if at least two of the following findings are present: (1) Brucella positive blood and/or bone marrow aspirate culture, (2) significantly high titers of Brucella agglutination test, (3) radiographs showing skeletal involvement typical of osteomyelitis or spondylodiscitis, and (4) biopsy suggestive of brucellosis with non-caseating granulomatous tissue[10]. In our case, the patient showed significant B. abortus agglutination titers of 1:320 and MRI findings consistent of D10-D11 infective spondylodiscitis; hence, he was diagnosed with brucellar spondylodiscitis. The main aim of antimicrobial medications in brucellosis is to treat the disease and its symptoms and signs and to prevent relapses. There is no standard treatment for osteoarticular brucellosis and experts prescribe medications depending on their personal experiences and the severity of the disease. Over the course of 6 months, a triple regimen of Streptomycin (1g daily), Doxycycline (10mg twice day), and Rifampin (15 mg/kg daily) exhibited 100% efficacy against spinal brucellosis [12]. Double therapy with Doxycycline and Rifampin, on the other hand, was linked to relapses. Patients require long-term antibacterial treatment (typically for at least 3 months) to avoid relapses. Spondylodiscitis is the most severe form of musculoskeletal involvement of brucellosis, due to its potential to develop an epidural abscess, and should be treated promptly with decompression to reduce the risk of long-term neurological damage, if nerve compression occurs [8]. In terms of clinical presentation and serological data, there is a significant overlap between brucellosis and tuberculosis [13]. Vaccines based on live attenuated Brucella strains, such as B. abortus strain 19BA or 104M, have been used in various countries to protect high-risk populations, despite their short-term efficacy and high reactogenicity [1].

To prevent the development of drug-resistant tuberculosis, it is crucial to rule out brucellosis in all cases of suspected or proved tuberculosis before starting antimicrobial therapy. Because of the high incidence of skeletal and neurological complications despite multiple treatment regimens, this is considered the most severe form of brucellosis osteoarticular involvement. A high order of suspicion is required to make the diagnosis; therefore, serological tests for brucellosis are recommended in patients complaining of chronic back pain with uncommon presentation; and especially if imaging studies revealed features of spondylodiscitis. The key to successful therapy of individuals with the osteoarticular form of brucellosis is early and identification and optimal treatment of the disease. This is attainable by an early collaboration between an orthopedic surgeon and an infectious disease specialist.

Spinal brucellosis can mimic degenerative changes and other types of infection such as tuberculosis which require different forms of treatment; therefore in endemic areas, a high index of suspicion is important to make the diagnosis. Serological studies are important in establishing the diagnosis of brucellar spondylodiscitis. Delay in diagnosis and management of the disease may result in skeletal and neurological complications.

C.M.Kiran, Professorand Head, Department of Pathology, performed the histological examination of the tissue biopsy.

References

- 1.Beeching NJ. “Brucellosis.” In: Jameson JL, Fauci AS, Kasper DL, Hauser SL, Longo DL, Loscalzo J, editors. Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine. 20thed. New York: McGraw-Hill Education; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dewan E, Oberoi A, John B, Mathias A, Abraham D. Brucellar spondylodiscitis mimicking tuberculosis. CHRISMED J Health Res 2015;2:294-7. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hantzidis P, Papadopoulos A, Kalabakos C, Boursinos L, Dimitriou CG. Brucella cervical spondylitis complicated by spinal cord compression: A case report. Cases J 2009;2:6698. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lindahl JF, Vrentas CE, Deka RP, Hazarika RA, Rahman H, Bambal RG, et al. Brucellosis in India: Results of a collaborative workshop to define one health priorities. Trop Anim Health Prod 2020;52:387-96. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bouaziz MC, Ladeb MF, Chakroun M, Chaabane S. Spinal brucellosis: A review. Skeletal Radiol 2008;37:785-90. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Esmaeilnejad-Ganji SM, Esmaeilnejad-Ganji SM. Osteoarticular manifestations of human brucellosis: A review. World J Orthop 2019;10:54-62. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yagupsky P. Detection of brucellae in blood cultures. J Clin Microbiol 1999;37:3437-42. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mantur B, Parande A, Amarnath S, Patil G, Walvekar R, Desai A, et al. ELISA versus conventional methods of diagnosing endemic brucellosis. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2010;83:314-8. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kerr WR, McCaughey WJ, Coghlan JD, Payne DJ, Quaife RA, Robertson L, et al. Techniques and interpretations in the serological diagnosis of brucellosis in man. J Med Microbiol 1968;1:181-93. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Namiduru M, Karaoglan I, Gursoy S, Bayazit N, Sirikci A. Brucellosis of the spine: Evaluation of the clinical, laboratory, and radiological findings of 14 patients. Rheumatol Int 2004;24:125-9. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rizkalla JM, Alhreish K, Syed IY. Spinal brucellosis: A case report and review of the literature. J Orthop Case Rep 2021;11:1-5. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bayindir Y, Sonmez E, Aladag A, Buyukberber N. Comparison of five antimicrobial regimens for the treatment of brucellar spondylitis: A prospective, randomized study. J Chemother 2003;15:466-71. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dasari S, Naha K, Prabhu M. Brucellosis and tuberculosis: Clinical overlap and pitfalls. Asian Pac J Trop Med 2013;6:823-5. [Google Scholar]