In an isolated LCL injury of the knee which is difficult to diagnose correctly without objective instability on radiographic evaluations and manual tests, it is important to consider patient history and physical findings.

Dr. Yoshinori Soda, Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, Hiroshima City Hiroshima Citizens Hospital, Hiroshima, Japan. E-mail: ysoda35@ybb.ne.jp

Introduction: We report a rare case of surgical treatment for an isolated lateral collateral ligament (LCL) injury of the knee that was difficult to correctly diagnose considering physical findings alone of a judo athlete.

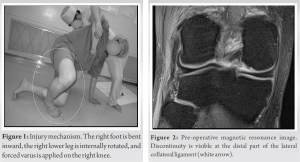

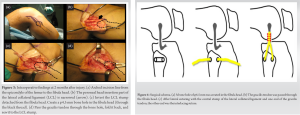

Case Report: The 27-year-old man complained of pain on the lateral side of the right knee and discomfort and balance instability when climbing and descending stairs. During a judo match, he stepped on his right foot to prevent his opponent’s waza (techniques), causing forced varus on his knee in a slight flexion position. His right knee showed no apparent sway in the manual test, but pain around the fibular head was induced in the figure-of-four position, and the LCL could not be palpated. Joint instability was not detected on varus stress roentgenography, but magnetic resonance imaging showed signal changes and an abnormal course in the fibula head insertion at the distal part of the LCL. Although no instability was observed objectively, clinical findings diagnosed LCL as an isolated injury, and surgical treatment was performed. Six months after the operation, his symptoms improved, and he resumed competing in judo.

Conclusion: To correctly diagnose an isolated LCL injury of the knee, it is important to consider patient history and physical findings. Repair of the injury could improve subjective symptoms, such as pain, discomfort, and balance instability, even if objective instability is not observed.

Keywords: Lateral collateral ligament, knee, ligament repair, judo.

The lateral collateral ligament (LCL) of the knee joint is among the main components of the posterolateral corner (PLC), together with the popliteus tendon and the popliteofibular ligament. PLC injuries often occur concomitant with injuries of other ligaments, such as posterior cruciate ligament (PCL) injuries; however, cases of isolated LCL injuries are rare. We report a surgical case of an isolated LCL injury of the knee that occurred during a judo competition.

The patient was a man in his 20s whose main complaints were pain in the lateral side of the right knee and discomfort and balance instability when climbing and descending stairs, especially during stair descent. During a judo match, he was injured when he twisted his right knee and consulted a local doctor. He was referred to our department 5 days after the incident under suspicion of injury to his right anterior cruciate ligament (ACL). He was asked about the details of the injury. During the match, he attempted to resist his opponent by trying not to be lifted while on all fours, with his right knee flexed and his right foot firmly planted on the floor. We inferred that he was injured while changing his foot position and that his lower leg was subjected to internal rotation, causing forced varus on his knee and leading to the injury (Fig. 1).

The LCL is the first restraint for knee varus in the entire range of motion [1, 2]. LCL injuries often occur as part of PLC injuries associated with cruciate ligament injuries in sports injuries [3]; however, isolated LCL injuries are rare, and only a few cases have been reported [1, 4, 5, 6]. LCL injuries are diagnosed using a manual varus stress test; however, it may be impossible to confirm instability, as in this case. Thus, pain was induced around the fibular head in the figure-of-four position, and the LCL was not palpable [7]. This was termed as a “Brighton sign” by Fitzpatrick et al. [6]. In addition to physical findings, imaging findings are useful for diagnosing ligament injury in the knee. In an isolated LCL injury, as in this case, after excluding comorbid injuries, such as ACL, PCL, and medial collateral ligament injuries, it is necessary to utilize stress X-ray examinations [8] and MRI [9] as auxiliary diagnostic tools for instability evaluation. However, inquiring about the details of the injury seems to be of utmost importance. In this case, the patient resisted his opponent by trying not to be lifted by firmly planting his foot on the floor while he was on all fours during a judo match. Internal rotation force was applied to the lower leg; varus was forced in the knee flexion position, and the LCL became tense and collapsed [10]. To date, the mechanism of LCL damage remains unclear. In football, it is easy to understand that an external force (internal reaction force) is directly applied in the knee extension position to cause LCL injury. However, in non-contact sports, such as yoga, rock climbing, and Jiu-Jitsu, varus force is applied at 0–60° of knee flexion [5, 11, 12]. In other words, the varus force and the rotational force applied to the lower leg (maximum interna and external rotations) may cause tension in the LCL, leading to collapse. The mechanism is similar in this case (Fig. 6). Regarding treatment, Sikka et al. [11] mentioned that performing conservative and surgical treatments produce good results, although only a few reports demonstrating this are available. Patel and Parker [5] performed conservative treatment on patients injured by repeatedly bending and applying varus force on the knee joint with their legs crossed behind their heads during yoga; mild instability remained, but the clinical course was good. Bushnell et al. [4] reported that nine National Football League athletes were treated conservatively or surgically, all of whom were able to return to competition. Haddad et al. [13] successfully treated wrestlers using conservative treatment, and they resumed competition without pain. In: these reports, surgery and conservative treatment were performed in cases of objective instability, and there were no reports of subjective symptoms, such as in our case. In general, surgery can improve objective instability; therefore, surgery is indicated if there are symptoms. However, although objective instability cannot be proven, it is necessary to determine the treatment policy by examining the injury mechanism and physical findings in detail.

To correctly diagnose an isolated LCL injury of the knee, it is necessary to decide the treatment policy with an emphasis on history and physical findings. Even if objective instability is not observed, surgical LCL repair could improve subjective symptoms, such as pain, discomfort, and balance instability.

Correctly diagnosing an isolated LCL injury of the knee is difficult. In cases of injuries without objective instability on radiographic evaluations and manual tests, it is important to determine the history and physical findings. Surgical intervention for LCL injury could improve subjective symptoms, such as pain, discomfort, and balance instability.

References

- 1.Coobs BR, LaPrade RF, Griffith CJ, Nelson BJ. Biomechanical analysis of an isolated fibular (lateral) collateral ligament reconstruction using an autogenous semitendinosus graft. Am J Sports Med 2007;35:1521-7. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grood ES, Noyes FR, Butler DL, Suntay WJ. Ligamentous and capsular restraints preventing straight medial and lateral laxity in intact human cadaver knees. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1981;63:1257-69. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Majewski M, Susanne H, Klaus S. Epidemiology of athletic knee injuries: A 10-year study. Knee 2006;13:184-8. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bushnell BD, Bitting SS, Crain JM, Boublik M, Schlegel TF. Treatment of magnetic resonance imaging-documented isolated grade III lateral collateral ligament injuries in National Football League athletes. Am J Sports Med 2010;38:86-91. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Patel SC, Parker DA. Isolated rupture of the lateral collateral ligament during yoga practice: A case report. J Orthop Surg (Hong Kong) 2008;16:378-80. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fitzpatrick D, Dursun M, Webborn N. Two cases of lateral collateral ligament knee strain in footballers presenting with a novel mechanism of injury and novel examination findings. Arch Physiother Rehabil 2019;2:41-5. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Meislin RJ. Managing collateral ligament tears of the knee. Phys Sportsmed 1996;24:67-80. [Google Scholar]

- 8.LaPrade RF, Gilbert TJ, Bollom TS, Wentorf F, Chaljub G. The magnetic resonance imaging appearance of individual structures of the posterolateral knee. A prospective study of normal knees and knees with surgically verified grade III injuries. Am J Sports Med 2000;28:191-9. [Google Scholar]

- 9.LaPrade RF, Heikes C, Bakker AJ, Jakobsen RB. The reproducibility and repeatability of varus stress radiographs in the assessment of isolated fibular collateral ligament and grade-III posterolateral knee injuries. An in vitro biomechanical study. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2008;90:2069- 76. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brantigan OC, Voshell AF. The mechanics of the ligaments and menisci of the knee joint. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1941;23:44-66. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sikka RS, Dhami R, Dunlay R, Boyd JL. Isolated fibular collateral ligament injuries in athletes. Sports Med Arthrosc Rev 2015;23:17-21. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baker CL Jr., Norwood LA, Hughston JC. Acute combined posterior cruciate and posterolateral instability of the knee. Am J Sports Med 1984;12:204-8. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Haddad MA, Budi ch JM, Eckenrode BJ. Conservative management of an isolated grade III lateral collateral ligament injury in an adolescent multi-sport athlete: A case report. Int J Sports Phys Ther 2016;11:596-606. [Google Scholar]