Each classification system for cervical spine injury has its drawback, cannot be universalized, and more research is needed to develop a classification system with an international agreement for diagnosing, classifying, and treating the injury for better patient outcomes.

Dr. Ankit Gaurav, Department of Orthopaedics, Postgraduate Institute of Medical Education and Research, Chandigarh - 160 012, India. E-mail: ankitgaurav1994@yahoo.com

Introduction: The sub axial cervical spine is a common site for traumatic spine injury, the injury of which can be life-threatening and can also result in permanent disability. Subaxial cervical spine injury has been classified by Allen and Ferguson (earliest classification), subaxial cervical spine injury classification system (SLICS) and AO spine classification. Allen and Ferguson system has significant inter- observer variations and is difficult to apply clinically at times. SLICS does not guide in the choice of surgical approach and score can vary between individuals because of different magnetic resonance imaging interpretations for discoligamentous injury. AO spine classification system has low agreement rate for intermediate morphology types (A1-4 and B) and not all injury patterns fit in the AO spine classification system like the case presented herein. In this case report, we address an unusual presentation of the flexion-compression mechanism of injury. This fracture morphology does not fit in any of the above mentioned classification system, so we are reporting this case and this is the first report of this kind in the literature.

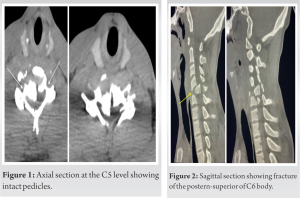

Case Report: An 18-year-old male presented to our emergency department with a history of fall of heavy object on his head from above. On presentation, the patient was in shock and respiratory distress. The patient was intubated and resuscitated gradually. Non-contrast computed tomography of the cervical spine showed isolated retropulsion of the C5 body without any displacement of facet joints or pedicle fracture. This injury was also associated with a fracture of the posterosuperior portion of the C6 vertebral body. The outcome was the death of the patient 2 days after injury.

Conclusion: The cervical spine is a common segment of the spine that is prone to injuries due to its anatomy and flexibility. The same injury mechanism can lead to varied and unique presentations. Each classification system for cervical spine injury has its drawback, cannot be universalized, and more research is needed to develop a classification system with an international agreement for diagnosing, classifying, and treating the injury for better patient outcomes.

Keywords: Flexion-compression, nutcracker, retropulsion, traumatic cervical spine, classification.

Cervical spine injuries can be potentially life-threatening and also carry a high morbidity burden for the surviving patients [1]. There are large variations in incidence, prevalence, mechanism of injury, gender distribution, and age group distribution for cervical spine injury in various parts of the world. Injury due to fall from height and motor vehicle accidents is the common causes leading to cervical spine injury. A male preponderance is observed in cases of cervical spine injury and most victims are in the age group of 15–45 years [2, 3]. There is also increased risk of cervical spine injury in patients of traumatic brain injury with a positive computed tomography (CT) head scan [4]. People with cervical spine injury are at increased risk of mortality than the general population [5]. Allen et al. proposed the first mechanistic classification for the lower cervical spine injury and divided injury mechanisms into six types: Flexion-compression, flexion-distraction, extension-compression, extension-distraction, vertical compression, and lateral flexion [6]. In this case report, we address that an unusual presentation of flexion-compression mechanism of injury was this injury pattern neither resemble flexion compression pattern or AO type of burst pattern [7]. According AO spine classification, subaxial cervical spine injuries are classified based on morphology (radiological), neurological status, and clinical modifiers. This classification has low agreement rate for intermediate morphology types (A1-4 and B) [8].

An 18-year-old male presented to our emergency department with a history of fall of heavy metallic object on his head from above. On presentation, he was in shock and respiratory distress. Patient was intubated and resuscitated gradually. Philadelphia collar was applied. After stabilization, general physical examination was performed and the patient was not able to move any of his limbs voluntarily. Radiology of the patient including X-ray and non-contrast computed tomography (NCCT) scans of the head and spine was then performed. NCCT head demonstrated frontal contusion, and X-ray of cervical spine demonstrated an unusual radiological presentation of flexion compression injury mechanism of cervical spine injury. NCCT of cervical spine showed isolated retropulsion of C5 body without any displacement of facet joints or fracture of pedicle (Fig. 1). This injury was also associated with fracture of posterosuperior portion of C6 vertebral body (Fig. 2). The mechanism of injury was that the patient was standing at his workplace, and suddenly a large and heavy metallic pipe falls on to the frontal region of his head resulting in flexion-compression type of cervical spine injury and frontal contusion. This injury can be compared to a nutcracker fracture. Although it resembles a burst fracture, we can see intact superior and inferior end plates. Cervical traction was applied to relieve compression on cord. We could not operate him as soon as possible due to the poor general condition of the patient. The ultimate outcome was the death of the patient 2 days after injury.

Cervical spine is divided into two levels, Upper cervical spine (occiput to C2) and subaxial cervical spine (C3 to C7) due to the considerable anatomic differences between the two. Subaxial cervical has its own unique injury patterns due to the anatomy and more than half of the injuries occur between C5 and C7 [9]. Usually, flexion-compression injury results in compression fracture of anterior vertebral body and subluxation/dislocation of facet joints leading to translation of one vertebra over another [10]. This may also be associated with teardrop fracture of cervical spine. Unusually, in this case there was no subluxation of facet joints but there was isolated retropulsion of the body of C5 vertebra into the spinal canal leading to spinal cord injury. Furthermore, there was no associated pedicle fracture of C5. This injury pattern can be compared to a nutcracker mechanism where C5 vertebral body was crushed between C4 (loaded by weight of head and heavy metallic pipe) and C6 (body weight acting as a counterforce) [11]. This is a unique presentation of flexion-compression type of injury and it can lead to spinal cord injury which can be fatal.

Cervical spine is a common segment of the spine which is prone to injuries due to its anatomy and flexibility. The same injury mechanism can lead to varied and unique presentations. Each classification system for cervical spine injury has its drawback, cannot be universalized, and more research is needed to develop a classification system with an international agreement for diagnosing, classifying, and treating the injury for better patient outcomes.

This report emphasizes the need to identify varied presentations of an injury to the cervical spine and also to develop a universalized system for diagnosing, classifying, and treating the injury for better patient outcomes.

References

- 1.Bransford RJ, Alton TB, Patel AR, Bellabarba C. Upper cervical spine trauma. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 2014;22:718-29. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hagen EM, Rekand T, Gilhus NE, Grønning M. Traumatic spinal cord injuries--incidence, mechanisms and course. Tidsskr Nor Laegeforen 2012;132:831-7. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Khanpara S, Ruiz-Pardo D, Spence SC, West OC, Riascos R. Incidence of cervical spine fractures on CT: A study in a large level I trauma center. Emerg Radiol 2020;27:1-8. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thesleff T, Kataja A, Öhman J, Luoto TM. Head injuries and the risk of concurrent cervical spine fractures. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2017;159:907-914. Erratum in: Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2017;159:915-6. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sokolowski MJ, Jackson AP, Haak MH, Meyer PR Jr., Sokolowski MS. Acute mortality and complications of cervical spine injuries in the elderly at a single tertiary care center. J Spinal Disord Tech 2007;20:352-6. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Allen BL Jr., Ferguson RL, Lehmann TR, O’Brien RP. A mechanistic classification of closed, indirect fractures and dislocations of the lower cervical spine. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1982;7:1-27. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Divi SN, Schroeder GD, Oner FC, Kandziora F, Schnake KJ, Dvorak MF, et al. AOSpine-spine trauma classification system: the value of modifiers: A narrative review with commentary on evolving descriptive principles. Global Spine J 2019;9:77S-88S. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Da Silva OT, Sabba MF, Lira HI, Ghizoni E, Tedeschi H, Patel AA, et al. Evaluation of the reliability and validity of the newer AOSpine subaxial cervical injury classification (C-3 to C-7). J Neurosurg Spine 2016;25:303- 8. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aebi M. Surgical treatment of upper, middle and lower cervical injuries and non-unions by anterior procedures. Eur Spine J 2010;19 Suppl 1:S33-9. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sharif S, Ali MY, Sih IM, Parthiban J, Alves ÓL. Subaxial Cervical Spine Injuries: WFNS spine committee recommendations. Neurospine 2020;17:737-58 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Koch J, Rahimi F. Nutcracker fractures of the cuboid. J Foot Surg 1991;30:336-9. [Google Scholar]