In this case of osteoid osteoma of distal phalenx, we realized that although diagnosis of osteoid osteoma is difficult at such uncommon sites, intervention with total excision of the nidus will give good post post-operative clinical outcome and pain relief.

Dr. Niranjan Sunil Ghag, Department of Orthopaedics, Dr. Shankarrao Chavan Government Medical College, Nanded, Maharashtra, India. E-mail: niranjanghag95@gmail.com

Introduction: Although osteoid osteomas are relatively common lesion, sites such as distal phalanx are still rarely observed. These lesions present with characteristic nocturnal pain due to prostaglandins and may also be associated with clubbing. Diagnosis of these lesions at uncommon sites becomes tricky and 85% are misdiagnosed.

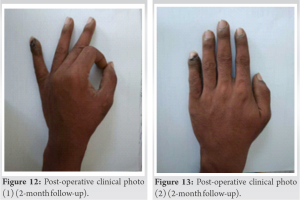

Case Report: A 18-year-old patient presented with the left distal phalanx of little finger clubbing and nocturnal pain (visual analogue scale [VAS] score: 8). After clinical workup and investigation to rule out infective and other causes, the patient was posted for excision of the lesion with curettage. Post-surgery outcome showed reduced pain (2 months post-operative VAS score: 1) and good clinical results.

Conclusion: Although osteoid osteoma of distal phalanx is a rare entity and difficult to diagnosed. Complete excision of lesion shows promising results both in terms of reduction of pain and functionally.

Keywords: Curettage, hand, little finger, osteoid osteoma, surgical excision, tumor.

Jaffe originally used the word “osteoid osteoma” to characterize the disease in 1935 [1]. It has previously been known by several other names [1]. In these lesions, prostaglandin levels are 100 to 1000 fold higher than in normal tissue [2]. They cause vasodilation and increased vascular permeability inside the tissues around the lesion, and they are thought to trigger tumor-related pain, which is traditionally described as nocturnal aches alleviated by salicylates [2]. Osteoid osteoma is a reasonably common benign skeleton tumor that occurs predominantly in the 2nd and 3rd decades of life, representing for around 11% of all benign bone tumors [3]. The most prevalent site for these pathologies is the long bones in the lower extremities, where this develops in 50% of cases [3]. The hand and wrist account for 5–15% of all osteoid osteoma cases, with the phalanx (proximal) and carpals being the most often affected. Lesions originating in the distal phalanx are unusual in that they frequently cause pulp edema and nail deformation [4]. In most cases, radiographs show a lytic lesion instead of the traditional look of reactive sclerosis encircling a central lucent nidus [4]. The rarity in osteoid osteomas in the hand (5–15% of all osteoid osteomas) and the lack of its typical appearance make diagnosis exceedingly difficult [5]. Approximately 85% of these instances are first misdiagnosed for one of the following reasons [5]:

1. The radiological appearance is unusual

2. Soft-tissue hypertrophy and nail deformities are present

3. Due to the distal phalanx’s tiny size, lesions are near to the nail, growth plate, and distal interphalangeal joint [6].

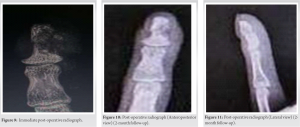

A right-handed 18-year-old male patient reported to the outpatient orthopedic department with swelling over the distal phalanx of his left-hand little finger that was steadily expanding and producing clubbing during a 6-month period. Swelling was linked to pain, which was worse at night and relieved with NSAIDs. Physical examination revealed localized edema with clubbing of the distal region of the left little finger, as well as an expanded nail plate and a disturbed nail fold angle. On comparing to the contralateral hand, the movement range at the distal interphalangeal joint was found to be normal. Before surgery, the patient had a visual analog scale (VAS) score of 8 (Figs. 1 and 2).

1. Osteoid osteoma

2. Chronic osteomyelitis with sequestrum

3. Intraosseous glomus tumor.

A provisional diagnosis of osteoid osteoma was made based on clinical and radiographic data; however, additional disorders such as blastoma, glomus tumor, and infection needed to be ruled out. The patient was operated on. The distal phalanx bone was revealed and cortex punctured using a medial approach. Nidus was curated with a curate followed by excision of the sclerotic margins with no additional puncture of the opposite cortex (Figs. 7 and 8).

Osteoid osteoma is considered as a benign osteoblastic tumor with an unknown cause [7, 8, 9]. It is most frequent before the age of 40, in the 2nd or 3rd decade of life [3], andaccounts for one tenth share of all benign tumors, with long bones of the lower leg accounting for 50% of the total. 5–15% occurs in the hand and wrist; however, the distal phalanx remains an unusual position [3]. Intramedullary (cancellous), cortical and subperiosteal osteoid osteomas are the three types of osteoid osteomas [9]. The most prevalent kind is cortical osteoid osteoma. This kind is commonly seen in the shafts of long bones, particularly the femur and tibia. The second most prevalent kind is cancellous (intramedullary) osteoid osteomas. The juxta-articular area of the femoral neck, the posterior components of the spine, and also the hands and feet are the most commonly affected regions. The most uncommon kind is subperiosteal osteoid osteoma, which generally manifests as a soft-tissue mass next to a bonycortex. Surrounding reaction changes are often minor or non-existent. The medial side of the femoral neck, as well as the hands and feet, is typical sites of involvement. The cancellous and subperiosteal variants, on the other hand, are thought to be more common in the tiny bones of the hand and foot [10]. In our case, osteoid osteoma appeared to be cancellous type. This osteoid osteoma of the distal phalanx of the little finger presented similarly, with nocturnal exacerbation of pain that responded to NSAIDS. With clinical presentation with swelling of distal phalanx and clubbing leading to disruption of nail fold angle. The radiography revealed a tiny lytic lesion/nidus development, which is typically smaller than 1 cm in diameter. The majority of osteoid osteomas are identified depending on a history of worsening night discomfort, clinical characteristics, and radiographic pictures [11]. When clinical and radiographic findings are aberrant, delayed diagnosis or misdiagnosis is not uncommon, according to a review of the literature [10]. This patient presented with typical nocturnal discomfort eased by NSAID, local enlargement of the finger and clubbed digit, and typical radiographic imaging of nidus development. The diagnosis of osteoid osteoma was obtained before surgery. Conventionally, the therapy for hand and feet osteoid osteoma has been en bloc excision or curettage of the nidus [10]. Rosenthal et al. introduced percutaneous radiofrequency ablation in 1992 as an alternate therapy with acceptable recurrence and post-operative complications [12]. Many experts, however, are concerned about the risk of neurovascular damage to finger if the procedure is used on the phalangeal bone [10]. Here, in our case, curettage and local excision of the lesion gave excellent outcome in terms of pain control which was the main reason for consultation also 6-month follow-up of patient did not show and signs of recurrence. Hence concluding that surgical excision with local debridement remains the standard treatment and yield best possible outcomes.

Distal phalanx osteoid osteoma is rare entity and differentiating and diagnosis making is challenging. Typical nocturnal pain with radiological findings of bony nidus helps in establishing diagnosis. Surgical excision of lesion will give good clinical outcome and pain relief with less chances of recurrence.

In this case of osteoid osteoma, we realized that although diagnosis of osteoid osteoma is difficult, intervention with total excision/curettage of the nidus will give good post-operative clinical outcome and pain relief.

References

- 1.Foucher G, Lemarechal P, Citron N, Merle M. Osteoid ostoma of distal phalanax: A report of four cases and review of the literature. J Hand Surg Br 1987;12:382-6. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hashemi J, Gharahdaghi M, Ansaripour E, Jedi F, Hashemi S. Radiological features of osteoid ostoma: Pictorial review. Iran J Radiol 2011;31:182-9. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Di Gennaro GL, Lampasi M, Bosco A, Donzelli O. Osteoid osteoma of the distal thumb phalanx: A case report. Chir Organi Mov 2008;92:179-82. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Athanasian EA. Bone and soft tissue tumors. In: Wolfe S, Hotchkiss RN, Pederson WC, Kozin SH, editors. Green’s Operative Hand Surgery. Philadelphia, PA: Churchil Livingstone Inc; 2011. p. 2141-95. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burger IM, McCarthy EF. Phalangeal osteoid osteomas in the hand: A diagnostic problem. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2004;427:198-203. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bowen CV, Dzus AK, Hardy DA. Osteoid osteomata of the distal phalanx. J Hand Surg Br 1987;12:387-90. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jaffe HL. Osteoid osteoma: A benign osteoblastic tumor composed of osteoid and atypical bone. Arch Surg 1935;31:709-28. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barca F, Acciaro AL, Recchioni MD. Osteoid osteoma of the phalanx: Enlargement of the toe: Two case reports. Foot Ankle Int 1998;19:388-93. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu YC, Hsu MC, Lin ZI. Unusual and complicated areas of juxta-articular osteoid osteoma: A report of two cases. J Orthop Surg ROC 2006;23:51-6. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tsang DS, Wu DY. Osteoid osteoma of phalangeal bone. J Formos Med Assoc 2008;107:582-6. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ramos L, Santos JA, Santos G, Guiral J. Radiofrequency ablation in osteoid osteoma of the finger. J Hand Surg 2005;30(A):798-802. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rosenthal DI, Hornicek FJ, Wolfe MW, Jennings LC, Gebhardt MC, Mankin HJ. Percutaneous radiofrequency coagulation of osteoid osteoma compared with operative treatment. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1998;80:815-21. [Google Scholar]