The prolonged and sustained antibiotic elution above the minimum inhibitory concentration and the osteogenic potential of antibiotic-loaded synthetic calcium sulphate beads is very effective in treating emphysematous osteomyelitis, where there is associated bone destruction and possibility for persistent infection.

Dr. Nizaj Nasimudeen, Department of Orthopaedics, Apollo Adlux Hospital, Kochi, Kerala, India. E-mail: drnizaj239@gmail.com

Introduction: Emphysematous osteomyelitis (EO) is an uncommon and deadly pathology characterized by occurrence of intraosseus air within the bone. However, only few of them have been reported. The use of local antibiotic delivery system has proven to be very effective in bone and joint infections as they offer decreased hospital stay and early clearance of infection. To the best of our knowledge, there are no reports on local antibiotic delivery using absorbable synthetic calcium sulfate beads in EO.

Case Report: A 59-year-old male with Type II diabetes mellitus, chronic kidney, and liver disease came with pain and swelling over left leg. After blood investigations and radiological evaluation, he was diagnosed to have EO of tibia with unknown source of infection. We successfully treated him with immediate surgical decompression and application of antibiotic impregnated absorbable calcium sulfate beads locally for improved local antibiotic delivery. Following this, he was further treated with culture sensitive intravenous antibiotics and his symptoms resolved.

Conclusion:Early diagnosis and aggressive surgical intervention along with local antimicrobial therapy using calcium sulfate beads can offer better outcome in EO. The local antibiotic delivery system can decrease the use of prolonged intravenous antibiotic therapy and long hospital stay.

Keywords: Emphysematous osteomyelitis, calcium sulphate beads, local antibiotics, intraosseus gas, stimulan, absorbable beads.

Emphysematous osteomyelitis (EO) is an uncommon disease having mortality as high as 32% [1]. The most common risk factors to EO are diabetes mellitus and malignancy and have no age or gender predilection [2]. The microbials causing EO include Escherichia coli, Klebsiella pneumonia, Enterobacter aerogenes, and Clostridium [3]. The high fatality associated with EO mandates aggressive early treatment. In the absence of any recent intervention, the presence of gas in the long bones is pathognomic of EO. The most common site of infection is the vertebrae, followed by pelvis, femur, tibia/fibula, foot, and sternum [4]. Even though plain radiographs and computed tomography are highly sensitive in demonstration of the air cavities, Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is a very valuable investigation in diagnosing EO. MRI can also reveal intraosseous gas and helps in detecting other signs such as bone marrow edema, abnormal contrast enhancement, and surrounding fluid collections, which help to accurately diagnose the infection and guide treatment [5]. Aggressive surgical intervention and antimicrobial therapy with local antibiotic delivery beads are required as EO are related with very high complications. Here, we describe the case of a patient with EO of tibia caused by K. pneumonia, which was treated successfully by surgical debridement and local antibiotic delivery using absorbable synthetic calcium sulfate beads. To the best of our knowledge, there are no reports on the use of antibiotic impregnated absorbable synthetic calcium sulfate beads in EO.

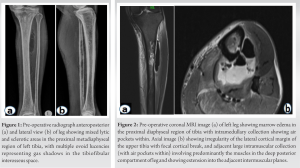

A 59-year-old male with Type 2 diabetes mellitus, chronic liver disease, and chronic kidney disease presented to the outpatient department with pain and swelling over anterior aspect of the left leg since 3 weeks. He had on and off episodes of fever and was agitated on presentation. He had no recent intervention or trauma to his left leg. On arrival, he was afebrile with vital signs within normal limits. The left leg was tender and swollen anterolaterally. The skin over the swelling was shiny and erythematous with no sinus. Distal pulse and sensations were intact. Laboratory investigations revealed elevated WBC count 15,000/mm3, ESR-103 mm/1st h, CRP-159 mg/L, HbA1C-12.6 %. Renal and liver function tests were abnormal (Creatinine-2.1 mg%, Bilirubin total-2.5 mg %). Urine culture showed no bacteriuria. Radiological evaluation with X-rays revealed mixed lytic and sclerotic areas in the proximal metadiaphyseal region of left tibia, with multiple ovoid lucencies representing gas shadows in the tibiofibular interosseous space (Fig. 1). Ultrasound of the left lower limb showed large collection in the posterior compartment of the left leg in intramuscular and intermuscular planes, with no evidence of deep vein thrombosis. Further investigation with MRI was done, considering the possibility of infection. MRI revealed marrow edema and intramedullary collection in the proximal tibial diaphysis showing air pockets within. There were cortical irregularity, focal cortical break of proximal tibia, and adjacent large intramuscular collection (with air pockets within) predominantly involving the muscles in the deep posterior compartment of leg (Fig. 2). The findings were consistent with EO of proximal tibia with infective myonecrosis.

He was taken immediately to the operation theater for surgical decompression. Approx. 70 ml of foul smelling chocolate colored pus with air bubbles drained (Fig. 3). The pus and the infected tissue were sent for culture sensitivity and histopathological evaluation. A cortical window was made over proximal tibia and medullary cavity was curetted. The medullary cavity and the adjuscent area around the bone were packed with Vancomycin + Gentamicin loaded absorbable calcium sulfate beads (STIMULAN) (Fig. 4). The culture of specimens revealed heavy growth of K. pneumoniae. The histopathology of the specimen was consistent with features of osteomyelitis (Fig. 5). Culture sensitive Piperacillin and Tazobactam was started intravenously. Over a period of 2 weeks, wound healed well. The general condition of the patient improved. His CRP came down to 1.2 mg/l, ESR-30/mm h, Creatinine to 1.2 mg%. The patient got discharged at 2 weeks after stopping the intravenous antibiotics.

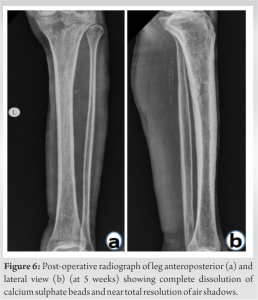

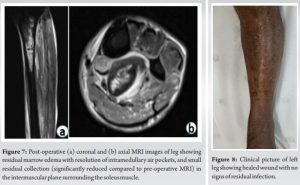

He had regular follow-up in outpatient clinic. X-rays done 5 weeks postoperatively (Fig. 6) showed complete dissolution of calcium sulfate beads and near total resolution of air shadows. MRI done at 2-month postoperatively (Fig. 7) showed resolution of intramedullary air pockets and small residual collection (significantly reduced compared to preoperative MRI) in intermuscular plane surrounding the soleus muscle. On his latest follow-up at 4 months, the patient is totally asymptomatic and is walking full weight bearing without support (Fig. 8).

The most common route of spread of EO is hematogenous; however, contiguous spreads from intra-abdominal, skin, and soft-tissue source of infection have also been reported [6].

Being a rare condition, no antibiotic protocols have been described in the literature for the treatment of EO. The antibiotics are usually given for 4–6 weeks as recommended in routine osteomyelitis treatment. However, the local delivery of antibiotic loaded calcium sulfate beads can decrease the duration of parenteral antibiotic therapy.

Despite multiple surgical debridements, the outcomes in EO have often been fatal [5]. The morbidity and mortality risk in this case of EO has increased several folds with the associated comorbidities such as diabetes, chronic liver, and kidney disease. Traditional antibiotic-loaded PMMA beads were used for local antibiotic delivery. However, they require surgical removal since they are non-biodegradable. When PMMA beads are left in situ for a longer period, the microbial cells irreversibly bind to the bead surface and get enclosed in a polysaccharide matrix forming a biofilm [7]. In addition, the bacteriae attached to cement beads gain resistance to the impregnated drugs as the PMMA releases sub inhibitory concentrations of antibiotics only from their surface. Furthermore, thermosensitive antibiotics cannot be delivered using PMMA beads because of the higher heat produced by PMMA [8]. In contrast, antibiotic-loaded calcium sulfate beads get absorbed completely, and releases its antibiotic load completely, resulting in higher elution and more sustained antibiotic concentrations over a period of several weeks. These resultant local drug concentrations are many times higher than the minimum inhibitory concentration for the causative pathogen, and with low systemic toxicity. The higher local concentration can even penetrate a biofilm. CS also induces expression of growth factors such as VEGF, TGF-β1, and BMP-2, which progressively increases with time and peaks at 4–6 weeks [9, 10]. The need of prolonged intravenous antibiotics, multiple surgeries, and long hospital stay can be significantly reduced with the use of these absorbable local antibiotic delivery system. However, the PMMA beads usage need a second surgery for its removal and have a considerably brief period of release such that the concentration of antibiotic drops to one-tenth of the initial levels within 24 h of its application.

Aggressive surgical intervention and local antimicrobial therapy with absorbable antibiotic loaded calcium sulfate beads can offer better outcome in EO, The use of local antibiotic delivery system is very effective in these cases as they offer decreased hospital stay and early clearance of infection, thereby decreasing significant morbidity and mortality.

The judicious use of absorbable local antibiotic beads can have excellent results in a fatal disease like EO where prolonged antibiotic therapy is required. In patients with multiple comorbidities, the use of local antibiotic carriers can even substitute the prolonged course of parenteral antibiotics, to lower the systemic toxicity.

References

- 1.Mautone M, Gray J, Naidoo P. A case of emphysematous osteomyelitis of the midfoot: Imaging findings and review of the literature. Case Rep Radiol 2014;2014:616184. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sung S, Lee BH, Kim JH, Park Y, Ha JW, Moon SH, et al. Emphysematous osteomyelitis of the spine: A rare case report. Medicine (Baltimore) 2020;99:e21113. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Luey C, Tooley D, Briggs S. Emphysematous osteomyelitis: A case report and review of the literature. Int J Infect Dis 2012;16:e216-20. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mujer MT, Rai MP, Hassanein M, Mitra S. Emphysematous osteomyelitis. BMJ Case Rep 2018;2018:1136. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sachdev IS, Tomer N, Bethapudi S, Priya S, Atwal S. A Rare case of emphysematous osteomyelitis of femur in an intravenous drug user. Cureus 2021;13:e16782. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Khanduri S, Singh M, Goyal A, Singh S. Emphysematous osteomyelitis: Report of two cases and review of literature. Indian J Radiol Imaging 2018;28:78-80. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Geurts JA, van Vugt TA, Arts JJ. Use of contemporary biomaterials in chronic osteomyelitis treatment: Clinical lessons learned and literature review. J Orthop Res 2021;39:258-64. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aiken SS, Cooper JJ, Florance H, Robinson MT, Michell S. Local release of antibiotics for surgical site infection management using high-purity calcium sulfate: An in vitro elution study. Surg Infect (Larchmt) 2015;16:54-61. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kallala R, Harris WE, Ibrahim M, Dipane M, McPherson E. Use of Stimulan absorbable calcium sulphate beads in revision lower limb arthroplasty: Safety profile and complication rates. Bone Joint Res 2018;7:570-9. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ma Y, Jiang N, Zhang X, Qin C, Wang L, Hu Y, et al. Calcium sulfate induced versus PMMA-induced membrane in a critical-sized femoral defect in a rat model. Sci Rep 2018;8:637. [Google Scholar]