The article displays a complex case of talus fracture-dislocation with a linear algorithm of treatment and tips and tricks of the surgical approach to such challenging cases.

Dr. Firas Kawtharani, Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, Southwest Medical Center, Liberal, United States. E-mail: firas.kawtharani@gmail.com

Introduction: Fractures of the talus and its associated hindfoot dislocations are uncommon. They usually result from high-energy trauma. These fractures can lead to permanent disability. Optimal treatment relies on accurate evaluation of the injury with proper imaging to identify the fracture pattern and associated injuries and to be able to make an appropriate pre-operative plan. Avoiding soft-tissue complications, avascular necrosis, and post-traumatic arthrosis are the main goal of treatment.

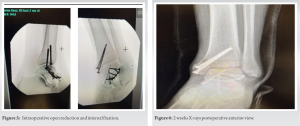

Case Report: We report a case of concomitant left talar neck and body fracture associated with a fracture of the medial malleolus in a 46-year-old male. We performed a closed reduction of the subtalar joint followed by an open reduction internal fixation of the talar neck/body and medial malleolus fractures.

Conclusion: At 12 weeks following the treatment, the patient had good movement with minimal discomfort on dorsiflexion, he was able to ambulate with no limp. Radiographs showed appropriate healing of the fracture. The patient was able to go back to his work with no restrictions as of publication of this report. Talus fracture dislocations are not benign in nature. Meticulous attention to soft-tissue management, anatomic reduction and fixation as well as adequate post-operative follow-up is needed to obtain a satisfactory outcome and avoid the detrimental sequalae of avascular necrosis and post-traumatic arthrosis.

Keywords: Talus fracture dislocation, anatomic reduction, avascular necrosis, post-traumatic arthritis, outcome, return to work.

The tarsal bones are 7 in number, the talus is the second largest tarsal bone that forms a link between the foot and the leg through the ankle joint. The incidence of these fractures is approximately 187/100,000 people each year [1]. The talus is 60–70% covered in articular cartilage, but has no muscular attachments, and articulates with adjacent bony structures through capsuloligamentous restraints [2], which makes it an important structure for ankle movement. Thus, a talar fracture will result in significant loss of motion and function. Fractures of the talus have a relatively low incidence, accounting for 0.3% of all bone fractures and 3.4% of fractures in the foot [3] with a significant male predilection, with up to 73% of talar fractures occurring in men [4]. These fractures occur in the neck of the talus more often than its head or body and cause severe pain, swelling, tenderness, and inability to put weight on the foot, with possible complications such as avascular necrosis, malunion, and/or post-traumatic arthritis.

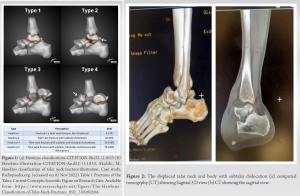

A 46-year-old male was at work climbing down a ladder when his foot twisted and fell sustaining a deformity in his ankle and foot. The patient was transferred subsequently to our emergency department, where he developed significant swelling and pain in the left ankle and foot. He denied any significant sensory or motor deficit. After a primary workup, he was found to have a displaced talar neck and body fracture with subtalar dislocation consistent with a Hawkins type 2 (Fig. 1) injury confirmed on radiographs and CT scan. Moreover, an associated medial malleolus fracture was found as well. Two stages were planned to approach this complex injury.

Talar fractures are divided based on the main anatomic divisions: Head, neck, body, lateral process fractures, and posterior process fractures. Talar neck fractures constitute about 50% of talar fractures, body fractures around 20%, lateral process 10% with the talar head fractures being the least common at 5% [5, 6]. With a normal range of movement in the ankle from 59° to 84° [7, 8, 9], the talus sometimes called the astragalus bone is the largest after the calcaneus bone, articulating with the distal tibia and fibula to form the ankle mortise. The talus has no muscle attachment and is held in place by various ligaments and a substantial articular interface, relying on its nutrient arteries in the talar neck and surrounding vessels interwoven through the capsule and ligaments for its blood supply [10]. A subtalar dislocation occurs through the disruption of two separate bony articulations: The talonavicular and talocalcaneal joints [11], furthermore, the region most sensitive to fractures is the neck of the talus, and of all talus fractures, the neck are considered the most frequent due to its relatively decreased amount of trabecular bone and its abrupt change in trabecular orientation [12]. In addition, the lack of muscular attachments and the absence of a secondary blood supply can lead to subsequent osteonecrosis [5]. Talus fractures comprise approximately 0.1–0.85% of all fractures [13] and regional injuries include malleolar fractures (in up to 44% of fracture cases), injuries to the calcaneus (in 11–18% of fracture cases), and concomitant metatarsal fractures (in up to 18% of fracture cases) [14, 15], they are associated with significant morbidity, malunion, avascular necrosis, and most notably post-traumatic arthritis with subtalar arthritis (50%) which is considered the most common complication followed by tibiotalar arthritis (33%) [16]. Fracture and dislocation of the talar neck and body as well as medial malleolus fracture are a rare and severe combination caused by high-energy trauma such as a motor vehicle accident or fall from height as seen in this case. This mechanism of injury results in axial loading with severe dorsiflexion of the ankle, forcing the talus to abut against the distal tibia causing a malleolar injury as well. We find in people with such injury the common symptoms of pain and hindfoot swelling as well as significant deformity. In addition to plain ankle and foot radiographs, CT of the ankle with 3D reconstruction is necessary for identifying the personality of the fracture. In addition, attention to detail is key in these fractures for instance, injuries related to the talar body can be difficult to visualize adequately in this setting because of the shape of the tibiotalar articulation and the overhang of the anterior and posterior tibial plafond [17]. Promptly closed reduction under procedural sedation or general anesthesia and possibly percutaneous stabilization and/or external fixation are the primary characteristics of treatment and must be done urgently to avoid ominous soft tissue and bony complications. Failure to reduce a displaced head or neck fracture can lead to secondary osteoarthrosis or avascular necrosis [18]. In fact, despite treatment, avascular necrosis or deep infection can still happen in a substantial number of cases. Following closed reduction, CT details are of utmost importance to document the talar fracture as well as additional bony injuries involving the subtalar joint and the adjacent bony structures of the hindfoot. In fact, subtle additional injuries are usually neglected in X-rays of the rearfoot but can result in significant problems such as degenerative arthritis or chronic ankle instability if unnoticed. Normally, the duration for a patient to recover and to get back the range of motion is still disputable. When the fracture is not complex instead of prescribing a rigorous regime of non-weight bearing patients are instructed and trained to start bearing weight as tolerated [19]. The case report focuses on a talar neck and body fracture and subtalar dislocation associated with medial malleolus fracture with an emphasis on a linear treatment algorithm and the expected outcome. A high level of evidence on treatment and prognosis of talar neck and body fractures associated with talar dislocations is not well established because of the infrequent nature of such fractures. Outstanding results are usually seen in straightforward talar fractures when directly treated by performing closed/open reduction. When the injury is complicated talar fractures whether closed or open with subtalar or tibiotalar dislocation, open reduction is often needed, with necessary anatomic reduction of the fracture and the joint with possibly supplemental external fixation and wound debridement if need be. High complication rates up to and even >60% are usually seen in such cases. This case report assists doctors working with a talar neck and body fracture and dislocation to formulate a plan of treatment for these complex injuries.

Displaced talar fractures remain a therapeutic challenge for orthopedic surgeons. Talar neck and body fracture-dislocation associated with a concomitant ankle fracture are rare and devastating injuries. Usually, a high-energy injury mechanism is involved. Radiographs including computed tomography are necessary. The poor outcome emanating from osteoarthritis or osteonecrosis of the talus after dislocation due to trauma is related to the initial injury with vascular compromise as result of subtalar dislocation. Thus, the treatment algorithm involves immediate reduction of any subtalar or tibiotalar dislocation followed by definitive fixation when soft tissue allows through a dual medial and lateral approach with medial or lateral malleolar osteotomy depending on the personality of the fracture. Attention to detail including associated fractures (like medial malleolus in our case) is paramount. Good outcomes can be obtained despite a high complication rate.

Talus fracture dislocations with associated ankle fractures like in our case can lead to a debilitating outcome if not treated adequately. Proper exposure with medial malleolus osteotomy is often needed to obtain a good result. Patients need to understand the nature of the injury and the possibility of avascular necrosis and post-traumatic arthritis even if all necessary measures of treatment were implemented.

References

- 1.Daly PJ, Fitzgerald RH Jr., Melton LJ, Ilstrup DM. Epidemiology of ankle fractures in Rochester, Minnesota. Acta Orthop Scand 1987;58:539-44. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schwartz AM, Runge WO, Hsu AR, Bariteau JT. Fractures of the talus: Current concepts. Foot Ankle Orthop 2020;13:2473011419900766. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mechchat A, Bensaad S, Shimi M, Elibrahimi A, Elmrini A. Unusual ankle fracture: A case report and literature review. J Clin Orthop 2014;5:103-6. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dale JD, Ha AS, Chew FS. Update on talar fracture patterns: A large level I trauma center study. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2013;201:1087-92. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Melenevsky Y, Mackey RA, Abrahams RB, Thomson NB 3rd. Talar fractures and dislocations: A radiologist’s guide to timely diagnosis and classification. Radiographics 2015;35:765-79. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Masciocchi C, Conchiglia A, Conti L, Barile A. Imaging of insufficiency fractures. In: Geriatric Imaging. Berlin Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag; 2013. p. 83-91. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hoppenfeld S. Physical Examination of the Spine and Extremities. New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts; 1976. p. 2235. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weseley MS, Koval R, Kleiger B. Roentgen measurements of ankle flexion--extension motion. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1969;65:167-74. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boone DC, Azen SP. Normal range of motion of joints in male subjects. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1979;61:756-9. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Singanamala N, Moore D, Davis D, Fung J. Internal fixation of a complex fracture of the Talus using a dual incision extensile approach-a case report with a review. J Foot Ankle Surg Tech Rep Cases 2022;2:100099. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Horning J, DiPreta J. Subtalar dislocation. Orthopedics 2009;32:904. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Frasca W, Nhan D. Case report: Talar neck fracture. J Educ Teach Emerg Med 2020;5 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fortin PT, Balazsy JE. Talus fractures: Evaluation and treatment. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 2001;9:114-27. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Berndt AL, Harty M. Transchondral fractures (osteochondritis dissecans) of the talus. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1959;41-A:988-1020 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gregory P, DiPasquale T, Herscovici D, Sanders R. Ipsilateral fractures of the talus and calcaneus. Foot Ankle Int 1996;17:701-5. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ben S. Talar Neck Fractures. Orthobullets; 2022. Available from: https://www.orthobullets.com/trauma/1048/talarneck-fractures [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ebraheim NA, Patil V, Owens C, Kandimalla Y. Clinical outcome of fractures of the talar body. Int Orthop 2008;32:773-7. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Early JS. Management of fractures of the talus: Body and head regions. Foot Ankle Clin 2004;9:709-22. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kalmet PH, Meys G, Horn YY, Evers SM, Seelen HA, Hustinx P, et al. Permissive weight bearing in trauma patients with fracture of the lower extremities: Prospective multicenter comparative cohort study. BMC Surg 2018;18:8. [Google Scholar]