Bony mallet fingers treated with pin fixation are at risk for ossification of the soft tissue.

Dr. Jeffrey A. Marchessault, Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, East Tennessee State University, James H. Quillen College of Medicine, P.O. Box 70582, Johnson City, 37614, Tennessee. Email: Jeffrey_marchess@hotmail.com

Introduction: Mallet finger is a common hand injury in sports in which the terminal extensor tendon is disrupted. This case report describes the rare occurrence of joint autofusion following surgical fixation of an unstable mallet finger injury.

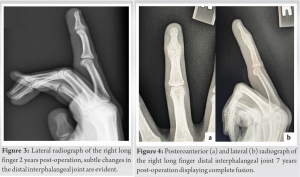

Case Report: We present a case of a 13-year-old right-hand dominant boy who sustained a right long finger bony mallet injury while playing football. Treatment consisted of closed reduction, percutaneous pinning of the right long finger distal interphalangeal (DIP) joint. He went on to heal with residual DIP joint stiffness and only 20° of residual motion that were noted on the early follow-up. Seven years later, he presented with no motion at the right long finger DIP joint. X-rays of his right long finger showed a complete fusion of bone across the DIP joint.

Conclusion: Autofusion as a complication of mallet finger surgery is an unprecedently rare finding, especially in the absence of any predisposing factors. This complication must be considered when treating mallet finger injuries through surgical intervention. Fortunately, the loss of DIP motion, complete in this case, had no long-term effect on the overall use of this patient’s hand.

Keywords: Bony mallet finger, adolescent, autofusion.

Mallet finger is a common hand injury in sports in which the terminal extensor tendon is disrupted. “Bony mallet” finger refers to the avulsion of the tendon attachment to the distal phalanx leading to the loss of the extensor mechanism involving the distal interphalangeal (DIP) joint. In many instances, mallet finger can be treated using non-operative splinting methods [1]. Surgical intervention is recommended in patients with unstable lesions with an avulsed fragment >30% of the articular surface of the base of the distal phalanx, those that do not reduce with full extension of the DIP, and those associated with volar joint subluxation [2]. Standard surgical techniques performed for injuries encompassed within these circumstances use compression fixation [3], screw fixation [4], and extension block pinning using either the Kirschner wire [5] or Ishiguro extension block [6] techniques. Early detection and appropriate treatment of bony mallet finger are crucial for achieving the most significant outcome for the patient. Bony mallet finger deformities can cause DIP joint dysfunction and if left untreated can affect the entire finger in the form of a swan neck deformity [7]. The unopposed flexor tendon flexes the DIP joint while retraction of the extensor mechanism, particularly the lateral bands, results in hyperextension of the proximal phalangeal joint. Over time, the finger is unable to flex toward the palm. Repairing the terminal tendon as closely as possible to its original length ensures the function of the finger, even when flexion of the DIP joint is not fully restored [8].

Then, a 13-year-old right-hand dominant boy sustained a bony mallet injury to his right long finger while jumping on a fumbled football. Injury radiographs revealed an avulsion-type fracture of the base of the right long finger distal phalanx involving 30% of the joint, in which the distal fragment was subluxed volarly (Fig. 1). The patient’s examination was significant for loss of active extension at the long finger DIP joint as well as generalized ligamentous laxity. The patient had hyperextension of both his elbows and knees, could extend his thumb back to his forearm, and hyperextend his 2nd metacarpal phalangeal (MCP) joint to 90°. Several family members had similar traits but no formal diagnosis had been made. He was offered surgical treatment based on the amount of joint subluxation and underwent closed reduction, percutaneous pinning of the right long finger DIP joint 9 days from injury. A two-pin technique was used, one across the DIP joint [9] and the other to block the bone fragment from retracting (Fig. 2).

Patients like the one described in our case report, an adolescent heavily involved in a ball-based sport, are consistent with the demographic of those who suffer mallet finger injuries. The patient’s presentation was significant for the hyperextensibility of additional joints. Laxity is an important consideration when addressing joint subluxation as it is a common predisposing factor in other upper extremity adolescent sports-related injuries, such as those involving the shoulder and elbow [10]. However, adjacent joint laxity has not been shown to influence the susceptibility of sustaining a mallet finger injury. The only correlations attributing to mallet finger are the injury usually occurring on the dominant hand’s long, ring, or small finger. Less confidently, there is a potential familial predisposition to injuries specifically involving the terminal extensor tendon [1, 11]. Non-operative treatment would not have had the most efficacious outcome as the fracture fragment measured 30%, and the joint was subluxed. Surgery through percutaneous pinning is an appropriate treatment method for the injury presented and was performed [10]. Treatment for mallet finger is most successful when surgical intervention is conducted preferably within 2 weeks but no later than 4 weeks of the initial injury, with an overall average length of 12 days from injury to surgery [2, 7, 12]. Adequate reduction of the bony fragment and immobilization of the DIP joint is the basic tenets of successful management. The risk of complications accompanies all medical procedures. Mallet finger surgery has an extensive list of documented complications, such as marginal skin necrosis, nail deformity, osteomyelitis, premature epiphyseal plate closure, and hypertrophy of the DIP joint [13]. On follow-up examination, persistent DIP joint stiffness and 20° residual motion would qualify this as only a fair outcome [7]. More interesting was the novel discovery of complete joint fusion 7 years after surgery. Ankylosis as a complication due to mallet finger surgery is unprecedently rare and has only been reported on one other occasion. It was observed in a study determining the outcomes of late presenting mallet finger fractures in which the mean interval from injury to initial operation was 57 days (range, 28–141 days). This complication was seen as such an anomaly that the patient was excluded from the study [14]. Ankylosis, the immobility of a joint due to a fibrous or bony union, can be a complication of a disease, injury, or purposeful manipulation from a surgical procedure. Fusion of the DIP joint in the long finger has weakened grip strength by 20–25% [15]. The decrease in grip strength has been attributed to the limited excursion of the flexor digitorum profundus tendon resulting in a quadriga effect. This was not the case with our patient. In chronic situations, fibrous ankylosis is the precursor for further progression to bony ankylosis of a joint. Very few factors attribute specifically to DIP ankylosis. The most notable causes are either genetic or inflammatory in nature. The genetic condition, symphalangism, is caused by a nonsense mutation of the NOG gene contributing to NOG-related-symphalangism spectrum disorder. Inflammatory diseases attributing complications include psoriatic and rheumatoid arthritis. Furthermore, a general cause of overall peripheral joint bony ankylosis can result from a secondary superimposed bacterial infection due to trauma or surgery [16]. Our patient’s medical history was insignificant concerning any of these factors.

This case report presents a 13-year-old boy with a bony mallet finger injury to the right long finger while jumping on a fumbled football. This is the first report of an autofusion of the DIP in an adolescent as the result of a bony mallet finger corrective surgery. His injury was appropriately diagnosed and treated, and he lacked all of the most prevalent pathologies predisposing an individual to increased susceptibility to post-surgical problems; yet, the treatment outcome resulted in DIP autofusion. Moreover, this complication occurred during the long-term healing process, between 2 and 7 years post-operation, and was discovered at a 7-year appointment for an unrelated injury. Educating the patient that extreme loss of mobility, at any point post-operation, is worth further investigation and could prevent long-term complications. Fortunately, the loss of DIP motion, complete in this case, had no long-term effect on the overall use of this patient’s hand.

Bony mallet finger autofusion post-pin fixation is an extremely rare complication that must be considered when treating mallet finger injuries through surgical intervention. Bringing awareness to this potential complication may serve as guidance for the future treatment of this injury, especially in the case of an adolescent.

References

- 1.Alla SR, Deal ND, Dempsey IJ. Current concepts: Mallet finger. Hand (N Y) 2014;9:138-44. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reddy M, Ho CA. Comparison of percutaneous reduction and pin fixation in acute and chronic pediatric mallet fractures. J Pediatr Orthop 2019;39:146-52. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yamanaka K, Sasaki T. Treatment of mallet fractures using compression fixation pins. J Hand Surg Br 1999;24:358-60. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kronlage SC, Faust D. Open reduction and screw fixation of mallet fractures. J Hand Surg Br 2004;29:135-8. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tetik C, Gudemez E. Modification of the extension block Kirschner wire technique for mallet fractures. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2002;404:284-90. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pegoli L, Toh S, Arai K, Fukuda A, Nishikawa S, Vallejo IG. The Ishiguro extension block technique for the treatment of mallet finger fracture: Indications and clinical results. J Hand Surg Br 2003;28:15-7. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Smit JM, Beets MR, Zeebregts CJ, Rood A, Welters CF. Treatment options for mallet finger: A review. Plast Reconstr Surg 2010;126:1624-9. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schweitzer TP, Rayan GM. The terminal tendon of the digital extensor mechanism: Part II, kinematic study. J Hand Surg Am 2004;29:903-8. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hofmeister EP, Mazurek MT, Shin AY, Bishop AT. Extension block pinning for large mallet fractures. J Hand Surg Am 2003;28:453-9. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kocher MS, Waters PM, Micheli LJ. Upper extremity injuries in the paediatric athlete. Sports Med 2000;30:117-35. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lamaris GA, Matthew MK. The diagnosis and management of mallet finger injuries. Hand (N Y) 2017;12:223-8. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Badia A, Riano F. A simple fixation method for unstable bony mallet finger. J Hand Surg Am 2004;29:1051-5. [Google Scholar]

- 13.King HJ, Shin SJ, Kang ES. Complications of operative treatment for mallet fractures of the distal phalanx. J Hand Surg Br 2001;26:28-31. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee HJ, Jeon IH, Kim PT, Oh CW, Deslivia MF, Lee SJ. Transtendinous wiring of mallet finger fractures presenting late. J Hand Surg Am 2014;39:2383-9. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Morgan WJ, Schulz LA, Chang JL. The impact of simulated distal interphalangeal joint fusion on grip strength. Orthopedics 2000;23:239-41. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vaishya R, Singh AK, Agarwal AK, Vijay V. Bilateral spontaneous bony ankylosis of the elbow following burn: A case report and review of the literature. J Orthop Case Rep 2018;8:43-6. [Google Scholar]