Clinical implications of a subacute form of necrotizing fasciitis, they can have a catastrophic end for the patient, if we are unaware of this entity existence as surgeons. A high index of suspicion and prompt surgical debridement is the highlights such a life-threatening infection.

Dr. Tramallino Jorge, Department of Orthopaedics and Traumatology, University Hospital of Charleroi, Charleroi, Belgium. E-mail: jorge@tramallino.com

Introduction: Necrotizing fasciitis (NF) is a life-threatening soft-tissue infection. While the fulminate form is well documented, the subacute NF is rarely reported. Failure to consider NF as a diagnosis during this indolent presentation can be detrimental to patients because the surgical aggressive debridement remains the key of the treatment.

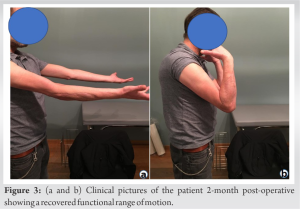

Case Report: We report a case of a 54-year-old man who developed a subacute NF. After an initial diagnosis of cellulitis, the patient failed to show improvement with antibiotic treatment; he was referred to our institution in view to benefit of a surgical management. The patient developed progressive systemic toxic symptoms and an emergency debridement was made 10 h after his admission. Our patient achieves to show improvement with antibiotic treatment, vacuum-assisted closure therapy, hyperbaric oxygen therapy, and reconstructive surgery. Complete recovery was observed after 2 months.

Conclusion: NF is a surgical emergency. Early diagnosis is essential, it is often ambiguous and commonly misdiagnosed including the subacute form. There needs to be a high suspicion for NF even in patients presenting with cellulitis without systemic symptoms.

Keywords: Necrotizing fasciitis, subacute necrotizing fasciitis, necrotizing soft-tissue infection, clinical spectrum.

Necrotizing fasciitis (NF), commonly known as flesh-eating disease, is a rapidly spreading soft-tissue infection that commonly affects the deeper layers of adipose tissue, fascia, or muscle and is frequently associated with systemic toxicity [1]. Diagnosis may be delayed by the fact that the disease progresses below the surface, beyond cutaneous manifestations hiding the severity of this disease [2]. The classic clinical presentation of NF (systemic disturbances and aggressive local symptoms) is well recognized. However, a less aggressive or atypical presentation such the subacute form may be a pitfall for the unexperienced surgeon due to the subtle symptomatology [2]. The existence of the subacute form is still debatable, although several cases have already been described in the literature. We present a case of subacute NF that was misdiagnosed and give a wake-up calling to the existence of this particular form of this life treating disease.

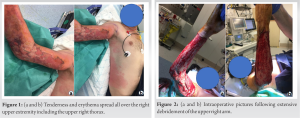

A 50-year-old man with a history of alcoholism was admitted to an emergency hospital, complaining of worsening pain and redness of the right elbow. There was a history of trivial trauma 2 days before this complaint. The X-ray of the elbow was negative, and the patient was discharged with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). The day after, the patient returned to the same emergency department because of the persistent erythema and tenderness around his elbow with no systemic inflammatory symptoms. On examination, a skin erythema, edema, warmness, and tenderness were detected on the right elbow, with no axillar lymphadenopathy. The rest of the physical examination was unremarkable. Results of laboratory tests included a white blood cell count of 7770/μL (normal 4000-10000), CRP 533.6 mg/L (0–5), hemoglobin 14.8 g/dL (13–17), glucose 0.83 g/L (0.75–1), creatine 1.4 mg/dL (0.7–1.2), and sodium 133 mmol/L (135–145) with a LRINEC score of 6. Kidney and liver function tests were normal, and a blood culture was negative. The diagnose of cellulitis was evoked and the patient was empirically treated with intravenous antibiotics (Cefazoline 4 g daily and Metronidazole 1500 mg daily). After 5 days, his condition continued to deteriorate with intense pain and significant edema and tenderness of his right elbow. A wound culture revealed a Streptococcus pyogenes infection. Over the course of 6 days, he was brought to our hospital for a surgical advice. On admission to our hospital, the patient was febrile (38°C) and his blood pressure was 148/83 mmHg. Laboratory analysis indicated a white blood cell count of 16000/μL (normal 4000–10000), a CRP 95 mg/L (0–5) and a LRINEC score of 3. Blood endotoxin was negative. The margins of tenderness and erythema spread all over the right upper extremity including the upper right thorax with phlyctens and areas of necrosis (Fig. 1). An emergency aggressive debridement of necrotic tissues was performed, under general anesthesia; after 7 days from his first visit at the emergency room (Fig. 2).

In 2004, Wong et al. designed a laboratory risk indicator “LRINEC score” to estimate the suspicion of NF. A score of 6 or higher indicates that NF should be seriously considered; however, the clinical suspicion is still superior to the LRINEC score [3]. Middle-aged and elderly patients (over 50 years old) were more likely to be infected and the most frequent comorbidity founded was diabetes mellitus [4]. Hypotension and pain disproportionated to local findings are considered as “red flags” for NF [5]. The masking effect of NSAIDs and antibiotics should be recognized, and absence of fever should not be used to rule out NF [2, 4]. A review proposed a clinical spectrum of NF in three forms: Subacute, acute, and fulminant [6]. The subacute form of NF like in the present case, the disease initially started as a superficial skin infection indistinguishable from cellulitis [6, 7]. The subacute form may lack of the classic clinical signs of NF and presents as a slowly progressive soft-tissue infection such as erysipelas or cellulitis, over a period of days to weeks [7]. A study by Andreasen et al. showed that despite a normal external appearance, soft tissue in patients with NF had extensive vascular micro thromboses as well as vasculitis [8]. That’s the reason why antibiotics may not reach the necrotic tissue because of vascular thrombosis [8]. Surgical exploration remains the most sensitive and specific option to confirm or exclude NF [9]. Limited cutaneous access is needed for the first step: The “finger test” [9]. This involves infiltration the suspect area with local anesthetics and performing a two cm incision down to the deep fascia. If the tissue lacks resistance and has non-contracting muscle, the finger test was considered positive [9]. Surgeons must avoid being cautious when it comes to the degree of surgical debridement. Surgical aggressive debridement at an early stage is mandatory regardless of whether it is subacute or classical NF [10]. Wong et al. recommend that debridement should be radical [11]. There is no consensus how to make this debridement, but Wong et al. classified the skin and subcutaneous component into three surgical zones, with a transitional area which can be potentially salvaged if the infection is rapidly controlled [11]. The amount of tissue that needs to be excised is a controversial issue, but when considered a radical debridement, both necrotic skin and fascia must be excised [11]. Even if tissue appears normal, an additional 5–10 mm margin of healthy tissue is also required to ensure complete source control [11]. Failure to remove all devitalized skin is the main reason for multiple operations [2]. Mok et al. have shown that the relative risk of death was 7.5 higher in cases of restrict primary debridement [12]. The VAC device could decrease the morbidities associated with wound care in NF, through the effective control of tissue edema, decrease bacterial count, and stimulation of the development of granulating tissue; but it comes with a higher need for surgical interventions requiring anesthesia [13]. Zannis et al. compared wet-dry saline dressing with VAC procedure and found in the case of the VAC therapy an increased on the rate of primary closure, providing micro strain of the wound; reducing the time of the hill wound and their cost [14]. Wong et al. proposed a four-stage grading system of subacute NF, from an indolent initial course without signs of systemic toxicity to a sudden deterioration to NF with septic features [15]. It could take more than 1 month after the onset of symptoms [15]. To Wong et al., the indolent initial course and gradual tissue necrosis with progressive cutaneous changes over the affected site should both be present to confirm the diagnose subacute NF [15]. Necrotizing soft-tissue infection themselves may induce conditions of low oxygen environment, and adjunct treatment of HBOT, in addition to surgery debridement and parenteral antibiotics may be beneficial in several ways, such as to minimize tissue loss and decrease the number of debridement required to achieve wound control [16, 17]. Increasing the supplies of tissue oxygen levels to inhibit bacterial growth [16, 17]. This case report is added to the list of scientific evidence that subacute NF is a clinical reality; however, its diagnosis remains ambiguous, and a better interpretation must be defined [7, 15, 18, 19]. In conclusion, frequent surgical debridement, extensive antibiotic therapy, and intensive support remain the cornerstone of treatment, even in this insidious progressive spectrum form.

NF represents a challenging condition for surgical teams. Early diagnosis is essential, but often delayed, especially in the subacute form. It is a surgical emergency, and the subacute form is not an exception to this rule. The patient should be admitted immediately in a surgical intensive care unit, where the surgical staff is skilled in performing extensive debridement and reconstructive surgery. In conclusion, this case report serves as a reminder that surgeons should maintain a high index of suspicion of NF, particularly in patients who present with unexplained limb pain and skin color change even with slowly progression. The subacute form of NF does exist and is probably under-reported.

Necrotizing fasciitis infection represents a broad spectrum of disease entities. The subacute form may go unnoticed due to the subtle symptomatology. Early diagnosis and surgical debridement remain the keystone of the treatment for all these forms. A high index of suspicion even for the slow progression pattern is the key point to successful achieve.

References

- 1.Wilson B. Necrotizing fasciitis. Am Surg 1952;18:416-31. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wong CH, Chang HC, Pasupathy S, Khin LW, Tan JL, Low CO. Necrotizing fasciitis: Clinical presentation, microbiology, and determinants of mortality. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2003;85:1454-60. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wong CH, Khin LW, Heng KS, Tan KC, Low CO. The LRINEC (laboratory risk indicator for necrotizing fasciitis) score: A tool for distinguishing necrotizing fasciitis from other soft tissue infections. Crit Care Med 2004;32:1535-41. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goh T, Goh LG, Ang CH, Wong CH. Early diagnosis of necrotizing fasciitis. Br J Surg 2014;101:e119-25. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Borschitz T, Schlicht S, Siegel E, Hanke E, von Stebut E. Improvement of a clinical score for necrotizing fasciitis: ‘Pain out of proportion’ and high CRP levels aid the diagnosis. PLoS One 2015;10:e0132775. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jarrett P, Rademaker M, Duffill M. The clinical spectrum of necrotising fasciitis. A review of 15 cases. Aust N Z J Med 1997;27:29-34. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Imamura Y, Kudo Y, Ishii Y, Shibuya H, Takayasu S. A case of subacute necrotizing fasciitis. J Dermatol 1995;22:960-3. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Andreasen TJ, Green SD, Childers BJ. Massive infectious soft-tissue injury: Diagnosis and management of necrotizing fasciitis and purpura fulminans. Plast Reconstr Surg 2001;107:1025-35. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lancerotto L, Tocco I, Salmaso R, Vindigni V, Bassetto F. Necrotizing fasciitis: Classification, diagnosis, and management. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 2012;72:560-6. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sarani B, Strong M, Pascual J, Schwab CW. Necrotizing fasciitis: Current concepts and review of the literature. J Am Coll Surg 2009;208:279-88. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wong CH, Yam AK, Tan AB, Song C. Approach to debridement in necrotizing fasciitis. Am J Surg 2008;196:e19-24. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mok MY, Wong SY, Chan TM, Tang WM, Wong WS, Lau CS. Necrotizing fasciitis in rheumatic diseases. Lupus 2006;15:380-3. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Franco-Buenaventura D, García-Perdomo HA. Vacuum-assisted closure device in the postoperative wound care for Fournier's gangrene: A systematic review. Int Urol Nephrol 2021;53:641-53. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zannis J, Angobaldo J, Marks M, DeFranzo A, David L, Molnar J, et al. Comparison of fasciotomy wound closures using traditional dressing changes and the vacuum-assisted closure device. Ann Plast Surg 2009;62:407-9. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wong CH, Wang YS. What is subacute necrotizing fasciitis? A proposed clinical diagnostic criteria. J Infect 2006;52:415-9. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mladenov A, Diehl K, Müller O, von Heymann C, Kopp S, Peitsch WK. Outcome of necrotizing fasciitis and Fournier's gangrene with and without hyperbaric oxygen therapy: A retrospective analysis over 10 years. World J Emerg Surg 2022;17:43. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jallali N, Withey S, Butler PE. Hyperbaric oxygen as adjuvant therapy in the management of necrotizing fasciitis. Am J Surg 2005;189:462-6. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Roberts M, Crasto D, Roy D. A case of subacute necrotizing fasciitis due to Serratia marcescens. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol 2021;14:55-8. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wong CH, Tan SH. Subacute necrotising fasciitis. Lancet 2004;364:1376. [Google Scholar]