The successful utilization of a gracillis free flap for reconstruction of a soft tissue defect in a patient with sickle cell disease.

Dr. Wesley Lemons, 417 N 11th street, Richmond VA 23298, Virginia. E-mail: wesley.lemons@vcuhealth.org

Introduction: Free tissue transfer in the sickle cell population presents many challenges to the reconstructive surgeon. There are few reported cases of successful free tissue transfers within the sickle cell population. The majority of successful cases involve fasciocutaneous free flaps with few successful muscle flaps. This case report describes the successful utilization of a gracillis free flap to reconstruct a multifocal soft tissue defect following a closed distal tibia fracture in a patient with sickle cell disease (SCD).

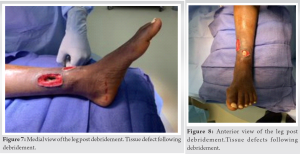

Case Report: This is a 20-year-old female with past medical history significant for sickle cell anemia, cardiomyopathy secondary to a ventricular septal defect and multiple occurrences of osteomyelitis who underwent gracilis free flap transfer to reconstruct soft tissue loss around the ankle after surgical fixation of a left pathological tibia fracture.

Conclusion: The use of free flaps in sickle cell patients has shown to be extremely challenging due to the high risks of sickling and subsequent pedicle thrombosis associated with this population. However, there have been an increasing number of successful cases of free tissue transfers with most of these flaps arising from muscular origins. Therefore, more cases regarding free flaps in the sickle cell population are needed to fully understand the best protocols to follow. The techniques utilized among successful cases, regarding protocols prior to the surgery along with successful graft location selection, can help advance future cases and shows promise for future sickle cell patients.

Keywords: Gracilis Free flap, sickle cell disease, lower limb defect, comminuted fracture.

Free tissue transfer within the sickle cell population has a high complication rate secondary to an elevated risk for thrombosis associated with the procedure which is compounded with the ischemia-related sickling inherent to the sickle cell disease (SCD) [1, 2, 3, 4, 5]. The choice of free flap depends greatly on the location and size of the skin defect. The most common free flap options for lower extremity reconstruction are the anterolateral thigh flap, the radial forearm flap, the lateral arm flap, the gracilis muscle flap, the rectus abdominis flap and lastly the latissimus dorsi flap and its variations [6]. I Gracilis free flaps are often thought of as the work horse of the lower extremity flaps with overall success rates in optimized patients ranging from 92% to 94% [9, 10]. Despite this high success rate, there has only been one previously reported successful free gracilis flap [8]. This case involved reconstruction of medial and anterior ankle wounds that resulted after necrosis of surgical incisions following intramedullary nailing of a distal tibia fracture in a patient with sickle anemia using a previously published protocol.

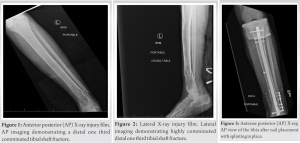

This is a 20 year old female with past medical history significant for sickle cell anemia, cardiomyopathy secondary to a ventricular septal defect and multiple occurrences of osteomyelitis who sustained a closed, distal third tibial shaft fracture through a segment of infarcted bone after a ground level fall (Fig. 1 and 2).

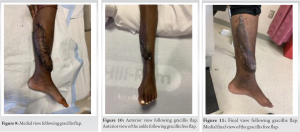

This case report describes the second published gracilis free flap in a patient with SCD using an anticoagulation protocol derived from previous successful published case reports. Most of the literature on free flaps in the sickle cell population are for the treatment of non-healing ulcers, as opposed to soft tissue defects secondary to trauma [4, 5, 6, 7, 8]. Wound reconstruction in the trauma population creates multiple additional challenges when compared to otherwise healthy patients seeking care for ulcers as trauma patients typically present with multiple different injuries, such as head traumas, lacerations, and penetrating injuries compounding already challenging cases. In addition, trauma patients tend to have more complex follow up regimens which can cause poorer compliance which further complicates outcomes due to the scarcity of published reports on free tissue transfer in patients with sickle cell, there is no one established perioperative protocol that has been widely adopted. This creates challenges when patients require free tissue transfer at facilities where this procedure is not commonly performed on this population. Often the nature of the injuries precludes transfer of these patients to higher volume centers which may have more experience in treating these problems. Certainly, if perioperative and anticoagulation protocols exist in high volume reconstructive microsurgery centers, publication of these protocols would be invaluable to other surgeons or institutions when they come across this problem. There is still limited data regarding free flap utilization within the sickle cell population and careful consideration should be taken with each case to determine what type of flap and the appropriate donor site. We implemented a successful perioperative protocol with a detailed anticoagulation plan and to successfully reconstructed lower extremity defects using a gracilis free flap in a patient with SCD. The details of this case including the anticoagulation management plan should be added to the literature for consideration in future cases. (Fig. 9-11).

There are few reported cases of free flaps utilized in the sickle cell population and even fewer of these cases were used to close a soft tissue defect following lower extremity trauma. Further publication of successful free tissue transfers in patients with sickle cell anemia including perioperative and anticoagulation protocols is necessary to improve patient outcomes. Thus, our patients’ successful flap placement can add to the existing literature and hopefully help in the success of future free flaps in this population.

The use of a free flap in the treatment of a soft tissue defect of a patient with SCD is not an absolute contraindication and should be considered as a viable treatment option for certain patients.

References

- 1.Buziashvili D, Zeri RS, Reisler T. Optimizing outcomes in pedicle and free flap reconstruction in patients with sickle cell trait. Eplasty 2018;18:ic2. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chan JK, Harry L, Williams G, Nanchahal J. Soft-tissue reconstruction of open fractures of the lower limb: Muscle versus fasciocutaneous flaps. Plast Reconstr Surg 2012;130:284e-95. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Khouri RK, Upton J. Bilateral lower limb salvage with free flaps in a patient with sickle cell ulcers. Ann Plast Surg 1991;27:574-6. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Posso C, Cuéllar-Ambrosi F. Successful lower leg microsurgical reconstruction in homozygous sickle cell disease: Case report. World J Hematol 2016;5:94-8. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Richards RS, Bowen CV, Glynn MF. Microsurgical free flap transfer in sickle cell disease. Ann Plast Surg 1992;29:278-81. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kozusko SD, Liu X, Riccio CA, Chang J, Boyd LC, Kokkalis Z, et al. Selecting a free flap for soft tissue coverage in lower extremity reconstruction. Injury 2019;50 Suppl 5:S32-9. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Weinzweig N, Schuler J, Marschall M, Koshy M. Lower limb salvage by microvascular free-tissue transfer in patients with homozygous sickle cell disease. Plast Reconstr Surg 1995;96:1154-61. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Spence RJ. The use of a free flap in homozygous sickle cell disease. Plast Reconstr Surg 1985;76:616-9. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Calotta NA, Pedreira R, Deune EG. The gracilis free flap is a viable option for large extremity wounds. Ann Plast Surg 2018;81:322-6. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Franco MJ, Nicoson MC, Parikh RP, Tung TH. Lower extremity reconstruction with free gracilis flaps. J Reconstr Microsurg 2017;33:218-24. [Google Scholar]