Alkaptonuria is a rare autosomal-recessive multisystemic disease hallmarked by exogenous or endogenous dark discoloration; knowledge about it helps to reduce any astonishment to orthopedic surgeons when encountered intraoperatively.

Dr. Ghadeer A Alsager, Department of Orthopaedics, King Saud Medical City, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. E-mail: ghadeer.alsagr@gmail.com

Introduction: Alkaptonuria (AKU) is a rare autosomal-recessive multisystemic disease. It is caused by a mutant homogentisate dioxygenase coding gene, leading to the acclamation of homogentisic acid (HGA), hence systemic manifestations. Renal manifestations and tendon rupture are rarely reported.

Case Report: We report a 60-year-old male with chronic kidney disease for over a decade who was initially misdiagnosed with ankylosing spondylitis and rheumatoid arthritis. Later on, the patient presented to our institute with a non-synchronized (8 years) acute quadriceps tendon rupture.

Conclusion: Physicians should be aware of the importance of prophylactic measures in the management of AKU, which is mainly medical management, to reduce the accumulation of HGA in the body. We further emphasize this point to reduce the incidence of subsequent tendon ruptures, as it significantly affects the quality of life.

Keywords: Alkaptonuria, kidney failure, tendon, rupture, quadriceps tendon.

Alkaptonuria (AKU) is a rare monogenic autosomal-recessive disease that appears in one in 250,000–1,000,000 live births in the United States [1]. It is caused by mutations in the homogentisate dioxygenase coding gene, preventing tyrosine from being metabolized properly, building-up of homogentisic acid (HGA), leading to a multisystemic disease [1]. Apart from urine darkening upon exposure to air AKU is usually silent in the early years of life. Ochronosis may start to manifest around the second to third decade of life [1, 2]. Ochronosis, i.e., alkaptonuric ochronosis from the word ochre meaning brownish-yellow pigment, is a terminology specific to AKU disease and refers to the clinical appearance of blue-black or gray-blue pigmentation [1, 3]. Ochronosis can be exogenous, depositing the eyes, ears, or skin, or can be endogenous, depositing in the connective tissue of cardiac valves and the musculoskeletal system, among other systems [1, 3]. Among musculoskeletal manifestations, ochronotic tendinopathy, leading to spontaneous tendon or ligament ruptures, accounts for 20–30% of patients [4]. Furthermore, kidney involvement in AKU is rare, with reports owning the etiology to nephrolithiasis [5]. The pathophysiologic mechanism involved in chronic kidney disease (CKD) and quadriceps tendon (QT) rupture is attributed, in theory, to the decrease in renal function leading to calcium, phosphorus, vitamin D, and parathyroid hormone (PTH) imbalance. This imbalance, mainly the high levels of PTH, increases bone turnover, which weakens the myotendinous junctions [4]. Herein, we report a case of sequential QT rupture in an elderly male with multiple risk factors, including CKD with secondary hyperparathyroidism and the use of systemic steroids due to misdiagnosed AKU. This manuscript has been prepared in accordance with the “Enhancing the Quality and Transparency of Health Care Research” Network’s research reporting guidelines of case reports “Care” [6].

Written consent was taken from the patient, and the patient agreed for participation and publication of his hospital course information and images.

Initial patient assessment

A 60 year-old-male is a known case of stage five CKD for the past 15 years with secondary hyperparathyroidism who was following at a private hospital and a recent diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis and ankylosing spondylitis 2 months before presentation with ongoing treatment of prednisolone and hydroxychloroquine. He presented to our institution with right knee pain after a simple fall from ground level 8 h before his presentation to our emergency department. The patient reported a previous history of similar injury 8 years ago; he reported a simple fall on his left leg sustaining acute left QT rupture, which was successfully repaired at another hospital.

Presenting symptoms

The patient was walking with a cane at home the morning of the incident, suffered a low-energy fall on his left knee, and felt a pop. He was unable to bear weight afterward. He went to a private hospital and underwent magnetic imaging radiographs magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the right knee, which showed QT complete rupture. Later that day, he presented to our emergency department.

Physical examination

The patient was hemodynamically stable, conscious, alert, and oriented. He had an old right knee surgical scar. The left knee had mild effusion with palpable left QT defect proximal to the patella. The patient could not do straight leg raise, and the distal neurovascular examination was intact.

Diagnostic evaluation

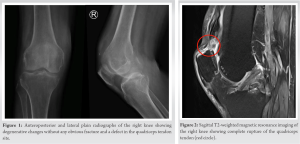

Anteroposterior (AP) and lateral plain radiographs of the right knee showed degenerative changes with no obvious fracture and a defect in the QT site (Fig. 1). MRI of the right knee showed the following: (1) Complete QT tear with retraction of about 3 cm with complete rupture of the medial patellofemoral ligaments, (2) Complex tear of the medial and lateral menisci with a flipped intra-articular meniscal fragment, (3) complete tear of the lateral collateral proper and popliteus tendon, and a (4) partial tear of the posterior cruciate ligament fibers with underlying mucoid degeneration (Fig. 2).

Initial therapeutic intervention

After confirming the diagnosis of acute right QT rupture, which we initially attributed to the use of systemic steroids along with CKD and chronic systemic disease, we planned and consented the patient for acute surgical repair.

Operative details

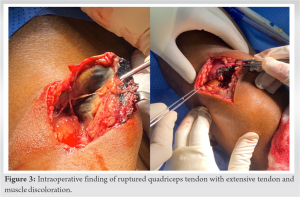

The patient was in a supine position under spinal anesthesia. The right lower limb was prepped and draped in standard fashion from the thigh to the mid of the leg. A midline skin incision was made over the knee to the proximal thigh. Superficial and deep dissection was carried out until reaching the QT. QT was identified, and incomplete avulsion was noted from lateral to medial; the vastus medialis oblique (VMO) muscle was still attached to the patella. There was extensive tendon and muscle discoloration and signs of necrosis going proximally up to 10 cm, sparing the VMO (Fig. 3). The distal femur was exposed and found to have discoloration of the articular cartilage surface and proximal pole of the patella (Fig. 4). Thus, due to the extensive necrosis involving the QT and muscles, a decision was made to debride and approximate QT. Debridement of the distal part of QT was carried out, and samples were sent for histopathology. Samples were taken from the synovium and proximal part of the lateral condyle of the femur. Irrigation of the wound and joint was done. The joint capsule was closed using vicryl, and QT was approximated to the patella using Ethilon and Vicryl suture. The wound was closed in layers. A sterile dressing and knee extension brace were applied.

Postoperative course

The patient tolerated surgery well; his right knee was in full extension, protected within the brace. We instructed him to avoid any range of motion. We disclosed the intraoperative findings to the patient, and he reported similar findings described to him after his first operation. The report of the previous surgery showed a complete tear of the QT with a necrotic tendon at the proximal and distal ends, which were debrided and repaired by two anchor sutures. As there was a high index of suspicion of AKU, a workup was sent for AKU, including genetics, urine HGA, whole exome sequencing, echocardiography, and whole spine MRI. Further history from the patient revealed a darkening of the urine. He has no similar family history; however, three of his sisters were diagnosed with rheumatoid arthritis. The results of the investigations were as follows: Histopathology showed deposit of acellular brown pigment and calcification with brown discoloration. MRI of the spine showed degenerative changes along with intervertebral disc calcification (Fig. 5). Urine HGA was positive and echocardiography revealed no abnormalities. We discharged the patient with regular follow-ups with nephrology, rheumatology, genetics, and orthopedics, with non-weight bearing instructions and knee extension with a knee immobilizer brace.

Follow-up visits and assessment of outcomes and interventions

Six weeks postoperatively, the wound healed well, and active knee exercises and full weight-bearing were allowed. Four months postoperatively, the patient could do a full range of motion in both flexion and extension.

In general, lower leg extensor mechanism ruptures are very rare. QT rupture was reported to have an incidence of 1.37/100,000. Extensor mechanism ruptures are most commonly unilateral. The most important risk factors for tendon rupture are advanced age and medical comorbidities, including diabetes mellitus, hyperparathyroidism, gout, CKD, obesity, and hypercholesterolemia, in addition to multiple connective tissue disorders, and chronic systematic diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, osteogenesis imperfect, and even AKU [2, 4]. As observed in the literature, Achilles tendon rupture tends to be the most commonly affected tendon. Ahmed et al. 2020 report on bilateral asynchronous spontaneous Achilles tendon rupture in AKU reported a total of 11 cases within the literature of Achilles tendon rupture among alkaptonuric patients [7]. Our literature review yielded seven other cases within the English literature of QT rupture among patients suffering from AKU [8-14]. Summary of the findings within the literature is in Table 1. Treatment options were the same as those with non-pathological QT rupture, with early surgical repair and strict postoperative immobilization. Repair was carried out by either end-to-end direct sutures [8, 9], patellar drill [10, 11, 12], or suture anchors [13]. Due to the extensive necrosis, our patient underwent primary end-to-end direct closure with good outcomes. The underlying pathophysiology of tendon rupture in AKU can be explained by the inhibition of collagen crosslinking due to deposition of HGA in the connective tissue of tendons, thus decreasing and interfering with the structural integrity of collagen, and eventually, spontaneous rupture and early degeneration of the cartilage [11, 13]. This deposition of HGA also explains the dark appearance of the affected tendon and cartilage [11, 13]. When there is clinician suspicion of AKU, diagnosis of AKU can only be confirmed by quantitative measurement of HGA in urine and mutation analysis of the HGD gene, especially in the absence of exogenous ochronosis, as the involvement of a multisystem can mimic many disorders [15]. As encountered in our case, in which a false diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis and ankylosing spondylitis was initially made. The spine involvement has been reported to mimic ankylosing spondylitis, with both having reduced intervertebral disc spaces and loss of lumbar lordosis on radiographs; however, AKU can be differentiated by sparing the sacroiliac joint, and the lumbar disc calcification [15]. The management of AKU is mainly supportive medical treatment aiming to reduce the build-up of HGA in the body, including tyrosine-restricted diet and adding a reducing agent such as ascorbic acid and nitisinone [14, 15].

AKU can mimic many disorders due to its systemic manifestations. However, exogenous or endogenous dark discoloration can be considered a hallmark of the disease, along with the darkening of the urine upon air exposure. With the emerging cases of tendinopathy and sequential tendon ruptures, prophylactic measures must be considered, including patient awareness and supportive medical treatment.

This article highlights the retrospective nature of diagnosing AKU often encountered in orthopedics, as shown by previous cases. Diagnosis is often first suspected by the finding of dark discoloration and confirmed by urine HGA. Orthopedic surgeons should be aware of the most common manifestation of AKU most importantly darkening of bone, joints, tendons, and muscles. AKU should be considered among the differential of spontaneous tendon rupture. Awareness of this disease will ease the management of such patients and will erase any confusion.

References

- 1.Zatkova A, Ranganath L, Kadasi L. Alkaptonuria: Current perspectives. Appl Clin Genet 2020;13:37-47. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wu K, Bauer E, Myung G, Fang MA. Musculoskeletal manifestations of alkaptonuria: A case report and literature review. Eur J Rheumatol 2018;6:98-101. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bhattar PA, Zawar VP, Godse KV, Patil SP, Nadkarni NJ, Gautam MM. Exogenous Ochronosis. Indian J Dermatol 2015;60:537-43. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pope JD, El Bitar Y, Mabrouk A, Plexousakis MP. Quadriceps tendon rupture. In: StatPearls. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing; 2023. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Faria B, Vidinha J, Pêgo C, Correia H, Sousa T. Impact of chronic kidney disease on the natural history of alkaptonuria. Clin Kidney J 2012;5:352-5. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gagnier JJ, Riley D, Altman DG, Moher D, Sox H, Kienle G, CARE Group. The CARE guidelines: Consensus-based clinical case reporting guideline development. Dtsch Arztebl Int 2013;110:603-8. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ahmed HM, Eltayeb A, Mohammed H, Mohammed AA, Hag SE. Bilateral Asynchronous spontaneous achilles tendon rupture in alkaptonuria: A case report. Sch J Appl Med Sci 2020;8:2685-9. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shetty S, Kumar A, Gupta S. Quadriceps tendon rupture-ochronosis an unusual cause. J Karnataka Orthop Assoc 2013;2:127. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Joes J. Ochronosis a cause of tendon rupture knee-a case report. J Pre Para Clin Sci 2020;6:4. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chua SY, Chang HC. Bilateral spontaneous rupture of the quadriceps tendon as an initial presentation of alkaptonuria--a case report. Knee 2006;13:408-10. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gorgile N, Modak A, Ahir H, Poriya H. A rare case of sequential tendon rupture in a patient with alkaptonuria with ochronotic arthropathy of knee joint. J Orthop Trauma Surg Rel Res 2022;17(10).72. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Krishnakumar R, Arun K. Spontaneous rupture of quadriceps tendon and total joint arthroplasty in Alkaptonuria. Kerala J Orthop 2012;25:30-3. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kumar EG, Kumar GM. Sequential tendon ruptures in ochronosis: A case report. Int J Res Orthop 2017;3:1235-8 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ngcelwane MV, Mandaba M, Bam TQ. Multiple tendon ruptures in ochronosis: Case report and review of prophylactic therapy. SA Orthop J 2013;12:55-7. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chu P, Cuellar MC, Bracken SJ, Tarrant TK. A mimic of ankylosing spondylitis, ochronosis: Case report and review of the literature. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep 2021;21:19. [Google Scholar]