To Study the Clinical Features, Radiological Findings, Treatment of a Child with C1-C2 Rotatory Subluxation.

Dr. Subhadeep Ghosh, Department of Spine Surgery, SKS Hospital and Post Graduate Medical Institute, Salem - 636 004, Tamil Nadu, India. E-mail: subhadeep210190@gmail.com/subhadeep2021@sksh.ac.in

Introduction: C1–2 rotatory subluxation is more commonly seen in children compared to in adults. It often has a history of respiratory tract infection, cervical trauma, and recent history of surgery of the head or neck.

Case Report: A 6-year-old boy presented to us with complaints of insidious onset of progressive deformity of the neck since the past 3 months. On examination, the patient had a classic “cock robin” deformity with his left head tilt and right-sided chin rotation. There was tenderness and spasm of the left sternocleidomastoid muscle. Radiologically, the child had unilateral C1–C2 facetal dislocation. There were associated abnormalities consisting of unilateral occiputoatlantal fusion and C2–C3 fusion. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed C1–C2 subluxation with kyphotic deformity the apex of which was impinging on the brainstem. The patient was put on skull traction with Crutchfield Tongs with progressively increasing weights for 1 week and serial X-rays were taken. Computed tomography (CT) scan was repeated at the end of 1 week which showed no improvement. C1–C2 open reduction and fusion was done. Post-operative period was uneventful. He improved on serial follow-ups. At follow-up at 18 months, the child remains comfortable, is going to school and doing all indoor and outdoor activities. His posture continues to be balanced. Radiologically, C1–C2 joint shows signs of a solid fusion.

Conclusion: A thorough history taking and a meticulous clinical examination if important for evaluation of torticollis in a child. Proper imaging helps in confirming the diagnosis and grading the severity. Prompt treatment is necessary for getting a good outcome.

Keywords: Torticollis, C1–C2 dislocation, Grisel’s syndrome, C1–C2 fusion.

C1–C2 rotatory subluxation is quite common in children. It often has a history suggestive of infection of the upper respiratory tract, trauma, or surgery of the head and neck region. This paper reports on a 6-year-old child with history suggestive of upper respiratory tract infection 4 months back and no history of recent significant trauma, or recent surgery, presenting to us with torticollis and limitations of neck movements [1-6].

A 6-year-old boy presented with complaints of gradually progressive deformity of the neck associated and painful stiffness of the left sternocleidomastoid and trapezius muscles since the past 3 months. He had mild neck pain and difficulties in neck movement. He did not have any difficulty in eating, buttoning his shirt, neither any problems in walking or playing. He was able to do activities of daily living with moderate discomfort. On examination, the patient had a classic “cock robin” deformity with his head being tilted to the left and chin turning to the right (Fig. 1). There was tenderness and spasm of the left sternocleidomastoid muscle without any hypertrophy. The child neither had any features of cervical radiculopathy nor any neurodeficits. Gait was normal.

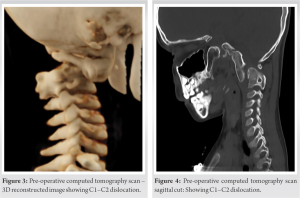

Radiologically, on X-rays, the child had unilateral C1–C2 facetal dislocation. There were associated abnormalities consisting of unilateral occiputoatlantal fusion and C2–C3 fusion (Figs. 2 and 3). CT scan revealed the same findings and the subluxation could be classified as Fielding and Hawkins type 1. CT scan and MRI showed C1–C2 subluxation with kyphotic deformity the apex of which was impinging on the brainstem (Fig. 4).

The patient was put on skull traction with Crutchfield Tongs with progressively increasing weights for 1 week and serial X-rays were taken. CT scan was repeated at the end of 1 week. Neither the X-rays not the CT scan showed any significant improvement. Hence, it was decided to take up the patient for open reduction and posterior instrumented fusion. C1–C2 open reduction and posterior instrumented fusion was performed by posterior midline approach. Bilateral C2 root had to be sacrificed for C1–C2 joint exposure. Joint was distracted and curetted. Lateral mass screws were inserted at C1, and pars screws were inserted at C2. Rods tightened over screws in compression reducing the subluxation, bone graft harvested from posterior iliac crest was inserted to ensure C1–C2 fusion.

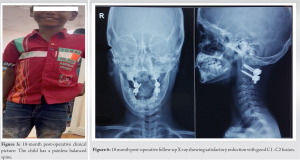

Post-operative period was uneventful. The neck was supported with a soft collar. Clinically, the child had a central position of the head with no residual tilt or rotation. Post-operative X-rays and CT scans showed anatomical reduction of C1–C2 joint with satisfactory positioning of instrumentation. At follow-up at 6 weeks after surgery, the child was comfortable and is carrying out all activities of daily living with minimal discomfort. His posture is balanced and gait is normal. The neck pain remains absent and he is showing signs of fusion.

At follow-up at 18 months, the child remains comfortable, is going to school, and doing all indoor and outdoor activities. His posture continues to be balanced (Fig. 5). Radiologically, C1–C2 joint shows signs of a solid fusion (Fig. 6).

Wortzman and Dewar, in 1968, were the pioneers in describing rotatory subluxation of the atlanto-occipital joint [7], and in 1977, Fielding and Hawkings, further, clarified the entity [8]. The C1–C2 joint shows a maximum rotation of 45°–47°. Further, rotation leads to the lateral inferior facet of C1 rocking over the lateral superior articular facet of the C2 vertebra [9]. It is seen in severe twisting injuries of the neck, as happens in motor vehicle accidents and violent sports injuries [10]. Cases have also been reported when the neck was inadvertently rotated to an angle for than 90° while the patient was under general anesthesia for some other procedure [11].

A thorough history taking and a meticulous clinical examination if important for evaluation of torticollis in a child. Proper imaging helps in confirming the diagnosis and grading the severity. Progressive follow-up with serial imaging is mandatory to monitor progress with traction. In absence of satisfactory, improvement with conservative means open reduction and fusion should be promptly considered to avoid neurological worsening or even a disaster.

A correct and timely diagnosis of C1–C2 dislocation leads to a good outcome.

References

- 1.White AA 3rd, Panjabi MM. The clinical biomechanics of the occipitoatlantoaxial complex. Orthop Clin North Am 1978;9:867-78. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kahn ML, Davidson R, Drummond DS. Acquired torticollis in children. Orthop Rev 1991;20:667-74. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ballock RT, Song KM. The prevalence of nonmuscular causes of torticollis in children. J Pediatr Orthop 1996;16:500-4. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nigrovic LE, Rogers AJ, Adelgais KM, Olsen CS, Leonard JR, Jaffe DM, et al. Utility of plain radiographs in detecting traumatic injuries of the cervical spine in children. Pediatr Emerg Care 2012;28:426-32. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tomczak KK, Rosman NP. Torticollis. J Child Neurol 2013;28:365-78. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Per H, Canpolat M, Tümtürk A, Gumuş H, Gokoglu A, Yikilmaz A, et al. Different etiologies of acquired torticollis in childhood. Childs Nerv Syst 2014;30:431-40. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wortzman A, Dewar FP. Rotary fixation of the atlantoaxial joint. Rotational atlantoaxial subluxation. Radiology 1968;90:479-87. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fielding JW, Hawkins RJ. Atlanto-axial rotatory fixation. (Fixed rotatory subluxation of the atlanto-axial joint). J Bone Joint Surg Am 1977;59:37-44. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Van Gilder JC, Menezes AH. The cranio-vertebral junction and its anomalies. New York: Futura; 1987. p. 206-8. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ono K, Yonenobu K, Fuji T, Okada K. Atlantoaxial rotatory fixation. Radiographic study. Spine 1985;10:602-8. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moore AP, Blumhardt LD. A double blind trial of botulinum toxin “a” in torticollis, with one year follow up. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1991;54:813-6. [Google Scholar]